Movies

Celluloid celebration

Avant garde lesbian filmmaker honored with series

Barbara Hammer says she wants viewers to take away power from her work. (Photo courtesy National Gallery of Art)

‘My Babushka: Searching Ukrainian Identities’ and ‘Diving Women of Jeju-Do’

53 minutes and 25 minutes respectively

Saturday at 3 p.m.

West Building Lecture Hall

‘Lover/Other’ and ‘Tender Fictions’

55 minutes and 58 minutes respectively

Sunday at 4 p.m.

West Building Lecture Hall

Admission is free; seating is first come-first seated basis. Doors open 30 minutes before each show. The West Building entrances are on the Mall, on 7th Street and on Constitution Ave. at 6th St., and on 4th St., N.W.

Details at nga.gov

Coming out and discovering her artistic voice in the medium of film were intertwined for Barbara Hammer, so much so that lesbian themes were almost inevitable in her work.

Hammer, 70, widely regarded as a pioneer in queer film, found herself drawn to documenting movement in her art classes. Eventually, she began to take film classes and was introduced to the work of one of the most influential avant-garde filmmakers of her time, Maya Deren.

Hammer watched Deren’s short film “Meshes in the Afternoon,” an experimental psychological film that has since become a cult hit in the avant-garde world of filmmaking.

“I knew then that I was right, that I was confirmed in my decision to be a filmmaker,” Hammer says. “I saw a woman expressing herself on screen from the inside out and not the way she had been constructed to be.”

At that time in her life, Hammer felt like she wanted to break free from the constrictions placed upon her in a similar way that Deren was doing in her filmmaking. She came out at age 30.

“Part of my construction being raised in the 1950s was to be a middle-class woman really living from the outside in,” Hammer says.

Hammer’s love for Deren resulted in the documentary “Maya Deren’s Sink” where Hammer visits Deren’s homes in New York and Los Angeles and shows the footage projected on a sink Deren owned.

That film, along with six others, is being shown as part of an exhibit, “American Originals: Barbara Hammer,” at the National Gallery of Art (6th and Constitution Ave., N.W.) through Sunday. Other films being show include “Generations,” “Resisting Paradise,” “My Babushka: Searching Ukrainian Identities,” “Diving Women of Jeju-Do,” “Lover/Other” and “Tender Fictions.”

Hammer will be in attendance on Sunday at 4 p.m. for the double-feature screenings of “Love/Other” and “Tender Fictions,” an autobiographical 58-minute documentary from 1995 that explores coming out and sexual identity and features Hammer’s partner of 28 years, Florrie Burke.

Her themes and subjects are all over the map, from the stories of surrealist artists and resistance fighters Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore in 2006’s “Love/Other” to the developing self-identities of contemporary women in the Ukraine following the post-Glasnost era of the 2001 piece “My Babushka,” to the women divers of South Koreas’s Jeju province who search for marine life off the coast in the 25-minute 2007 film “Diving Women of Jeju-Do.”

Although Hammer’s later work has included documentaries, her film style began in an avant-garde direction with hints of it present in her later work.

“When I came out, it had to be experimental,” she says. “We were like this first wave of lesbians arriving on the scene and changing the culture. We had to have a new way to speak.”

Since her beginnings as a lesbian filmmaker struggling to make a name for herself in a heteronormative-dominated film world, she has found her place among the ranks of successful queer cinema filmmakers. Hammer’s work has been displayed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the Tate Modern in London and the Jeu de Paume in Paris. People from all over the world have been able to experience her work and Hammer wants everyone to walk away from her films with one thing.

“I want them to take away power. Power in themselves, power in their bodies, power in their minds. Power to be active in the world,” Hammer says. “I want them to be motivated by the cinema that they’ve seen and ask questions in the world and to make statements.”

Although Hammer uses avant garde techniques to express her creativity and ideas, she believes queer cinema has come a long way from when she started and that there are many more ways to express queerness through filmmaking now.

She acknowledges that queer cinema can now be expressed through various different genres including documentaries, narrative storytelling, computer animation and cross-genre. She says the goal of all these genres in queer cinema is to create a new cinema.

Hammer hopes that when audiences watch her films, they come away feeling challenged.

“There’s room in the world for multiple aesthetics as there are multiple genders. So live and let live and make and make do and be creative and show your force.”

Movies

Trans filmmaker queers comic book genre with ‘People’s Joker’

Alternative ‘Batman’ universe a medium for mythologized autobiography

It might come as a shock to some comic book fans, but the idea of super heroes and super villains has always been very queer. Think about it: the dramatic skin-tight costumes, the dual identities and secret lives, the inability to fit in or connect because you are distanced from the “normal” world by your powers – all the standard tropes that define this genre of pop culture myth-making are so rich with obviously queer-coded subtext that it seems ludicrous to think anyone could miss it.

This is not to claim that all superhero stories are really parables about being queer, but, if we’re being honest some of them feel more like it than others; an obvious example is “Batman,” whose domestic life with a teenage boy as his “ward” and close companion has been raising eyebrows since 1940. The campy 1960s TV series did nothing to distance the character from such associations – probably the opposite, in fact – and Warner Brothers’ popular ‘80s-’90s series of film adaptations solidified them even more by ending with gay filmmaker Joel Schumacher’s much-maligned “Batman and Robin,” starring George Clooney and Chris O’Donnell in costumes that highlighted their nipples, which is arguably still the queerest superhero movie ever made.

Or at least it was. That title might now have to be transferred to “The People’s Joker,” which – as it emphatically and repeatedly reminds us – is a parody in no way affiliated with DC’s iconic “Batman” franchise or any of its characters, even though writer, director and star Vera Drew begins it with a dedication to “Mom and Joel Schumacher.” Parody it may be, but that doesn’t keep it from also serving up lots of food for serious thought to chew on between the laughs.

Set in a sort of comics-inspired dystopian meta-America where unsanctioned comedy is illegal, it’s the story of a young, closeted transgender comic (Drew) who leaves her small town home to travel to Gotham City and audition for “GCB” – the official government-produced sketch comedy show. Unfortunately, she’s not a very good comic, and after a rocky start she decides to leave to form a new comedy troupe (labeled “anti-comedy” to skirt legality issues) along with penguin-ish new friend Oswald Cobblepot (Nathan Faustyn). They collect an assortment of misfit would-be comedians to join them, and after branding herself as “Joker the Harlequin,” our protagonist starts to find her groove – but it will take negotiating a relationship with trans “bad boy” Mr. J (Kane Distler), a confrontation with her self-absorbed and transphobic mother (Lynn Downey), and making a choice between playing by the rules or breaking them before she can fully transition into the militant comic activist she was always meant to be.

Told as a wildly whimsical, mixed media narrative that combines live action with a quirky CGI production design and multiple styles of animation (with different animators for each sequence), “People’s Joker” is by no means the kind of big-budget blockbuster we expect from a movie about a superhero — or in this case, supervillain, though the topsy-turvy context of the story more or less reverses that distinction — but it should be obvious from the synopsis above that’s not what Drew was going for, anyway. Instead, the Emmy-nominated former editor uses her loopy vision of an alternative “Batman” universe as the medium for a kind of mythologized autobiography expressing her own real-life journey, both toward embracing her trans identity and forging a maverick career path in an industry that discourages nonconformity, while also spoofing the absurdities of modern culture. Subverting familiar tropes, yet skillfully weaving together multiple threads from the “real” DC Universe she’s appropriated with the detailed savvy of a die-hard fangirl, it’s an accomplishment likely to impress her fellow comic book fans — even if they can’t quite get behind the gender politics or her presentation of Batman himself (an animated version voiced by Phil Braun) as a closeted gay right-wing demagogue and serial sexual abuser.

These elements, of course, are meant to be deliberately provocative. Drew, like her screen alter ego, is a confrontation comic at heart, bent on shaking up the dominant paradigm at every opportunity. Yet although she takes aim at the expected targets – the patriarchy, toxic masculinity, corporate hypocrisy, etc. – she is equally adept at scoring hits against things like draconian ideals of political correctness and weaponized “cancel culture”, which are deployed with extreme prejudice from idealogues on both sides of the ideological divide. This means she might be risking the alienation of an audience which might otherwise be fully in her corner – but it also provides the ring of unbiased personal truth that keeps the movie from sliding into propaganda and elevates it, like “Barbie”, to the level of absurdist allegory.

Because ultimately, of course, the point of “People’s Joker” has little to do with the politics and social constructs it skewers along the way; at its core, it’s about the real human things that resonate with all of us, regardless of gender, sexuality, ideology, or even political parties: the need to feel loved, to feel supported, and most of all, to be fully actualized. That means the real heart of the film beats in the central thread of its troubled connection between mother and daughter, superbly rendered in both Drew and Downey’s performances, and it’s there that Joker is finally able to break free of her own self-imposed restrictions and simply “be” who she is.

Other performances deserve mention, too, such as Faustyn’s weirdly lovable “Penguin” stand-in and Outsider multi-hyphenate artist David Leibe Hart as Ra’s al Ghul – a seminal “Batman” villain here reimagined as a veteran comic that serves as a kind of Obi-Wan Kenobi figure in Joker’s quest. In the end, though, it’s Drew’s show from top to bottom, a showcase for not only her acting skills, which are enhanced by the obvious intelligence (including the emotional kind) she brings to the table, but her considerable talents as a writer, director, and editor.

For some viewers, admittedly, the low-budget vibe of this crowd-funded film might create an obstacle to appreciating the cleverness and artistic vision behind it, though Drew leans into the limitations to find remarkably creative ways to convey what she wants with the means she has at her disposal. Others, obviously, will have bigger problems with it than that. Indeed, the film, which debuted at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, was withdrawn from competition there and pulled from additional festival screenings after alleged corporate bullying (presumably from Warner Brothers, which owns the film rights to the Batman franchise) pressured Drew into holding it back. Clearly, concern over blowback from conservative fans – who would likely never see the film anyway – was enough to warrant strong arm techniques from nervous execs. Nevertheless, “The People’s Joker” made its first American appearance at LA’s Outfest in 2023, and is now receiving a rollout theatrical release that started on April 5 in New York, and continues this week in Los Angeles, with Washington DC and other cities to follow on April 12 and beyond.

If you’re in one of the places where it plays, we say it’s more than worth making the effort. If you’re not, never fear. A VOD/streaming release is sure to come soon.

Movies

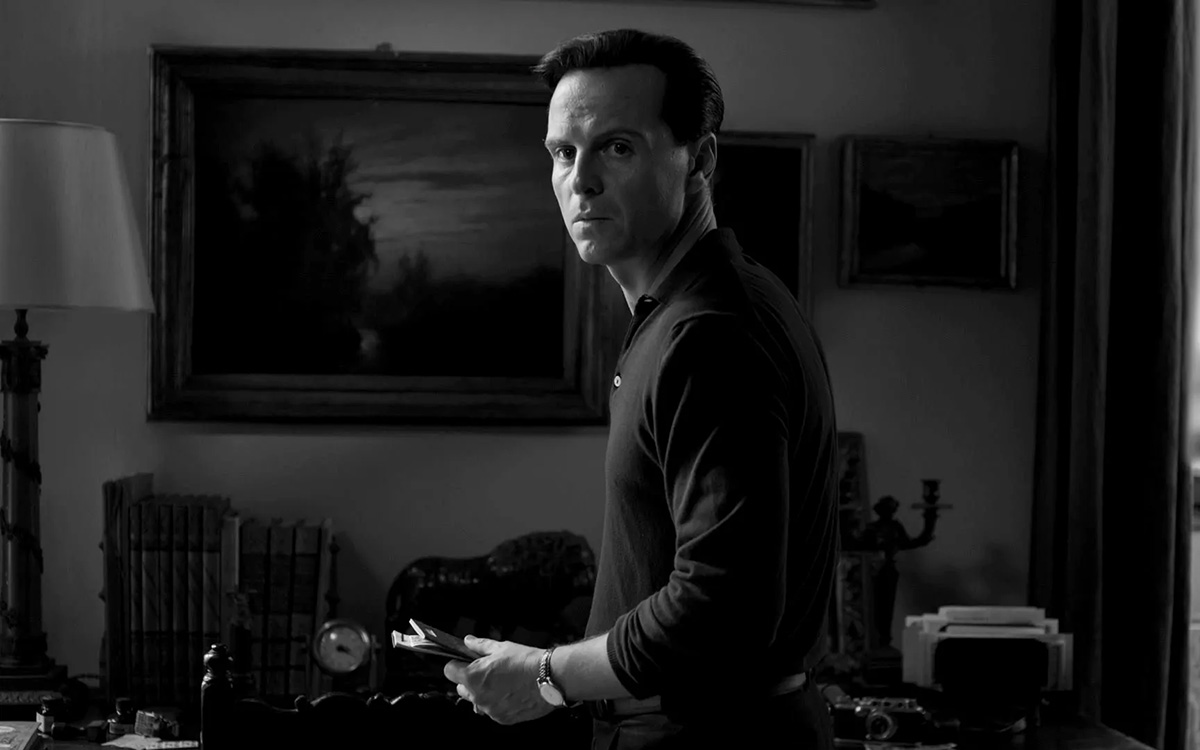

Star turn makes excellent ‘Ripley’ a showcase for Andrew Scott

Reasserting the queerness of an author who boldly pushed boundaries

There’s something about an anti-hero that appeals to us all. Why else would so many of our greatest stories revolve around a character whose behavior goes against everything we’ve been raised to believe is right?

Actually, that question probably answers itself. For many of us, the things we are raised to accept about life in the human world often feel less acceptable once we’ve gone through a few years of adult experience, which tends to put us at odds with the so-called “norms” of conformity. Naturally, this can be frustrating from time to time – and while that might not be enough to make us go “rogue” without regard law or ethics, it’s certainly sufficient to fuel our guilty fantasies.

That, along with the literary skills of Patricia Highsmith, the queer novelist who created him, is why the character of Tom Ripley has been engrossing us in various forms for nearly 75 years. The eponymous anti-hero of “The Talented Mr. Ripley” (originally published in 1955) went on to feature in three additional books by Highsmith, and was subsequently brought to life in multiple small-and-big-screen incarnations, perhaps most prominently by Matt Damon in Anthony Minghella’s 1999 film adaptation. These versions managed to skirt the book’s obvious queer subtext, but queer audiences recognized it anyway. Now, thanks to creator, writer, and director Steve Zaillian, Highsmith’s starry-eyed sociopath has returned in an eight-episode series – which pares the title down to the short-but-evocative “Ripley” – that debuts on Netflix April 4, and portrays his adventures with an eye toward honoring Highsmith’s intent while delivering the kind of up-front queerness that the author could never have dreamed of accomplishing in her heyday.

Not that this “Ripley” is exactly “out and proud,” though the actor who plays him – Andrew Scott (“All of Us Strangers”) – certainly is. The acclaimed Irish thespian brings his own queerness to the table in illuminating a character whose survival depends on never calling attention to himself – and though the series moves the action ahead a few years to1960, it’s still a world where any hint of “deviance” is likely to draw suspicion. That’s the last thing Tom Ripley needs; he’s a con artist, the mid-20th-century equivalent of modern-day “phishing” scammers, grifting gullible marks from his squalid, one-room New York City apartment. He’s good at what he does, an anonymous figure hiding in a sea of strangers – but when a wealthy shipping magnate tracks him down with a request for help and the offer of an all-expenses-paid excursion to Italy, he sees it as an opportunity to change his life for the better.

That opportunity, as it turns out, involves a barely remembered college acquaintance named Dickie (Johnny Flynn), whose post-graduation trip to Europe has become a years-long vacation on the Mediterranean coast from which his father – Ripley’s surprise benefactor – would like him to return. Sent on a mission to convince his old schoolmate to go home, he is instead spellbound by the idyllic seaside setting and opulent lifestyle that surrounds him – and also by Dickie himself. He ingratiates himself into the young man’s life, winning his sympathies despite some initial awkwardness. Not so easily persuaded is Dickie’s girlfriend, Marge (Dakota Fanning), whose lingering distrust must be overcome if Ripley is to enact his new master plan to claim Dickie’s life of expatriate luxury as his own.

Thanks to its source’s relative familiarity, “Ripley” makes no effort to hide the fact that its anti-hero is a shady guy; we see from the start that he’s a liar and an opportunist. What Zaillian manages to do, unlike others who have adapted the novel, is move past a clinical focus on Ripley’s psychology to give us a less prosaic – and therefore more complex – interpretation of the character. Much of this comes from a script that echoes Highsmith’s hard-boiled style by framing the story (and its protagonist) in a shadowy, amoral universe, enhanced by the stylish black-and-white treatment delivered by Robert Elswit’s cinematography, which leans into both the paradigm-challenging Euro “art cinema” from the period of its setting and the gritty chiaroscuro contrasts of film noir, setting up an instinctual understanding that this narrative, like its visuals, is composed entirely in shades of gray.

In the show’s engrossing first episode, this is a particularly effective hook, style coupling with context to underscore the bleakness of Ripley’s daily routine in New York, which is no less soul-crushing, perhaps, than the more lawful ones into which most of us are locked. Though we see that he’s a predator, it’s hard not to relate to his struggle, and by the time we get to the next chapter and meet Dickie and Marge, we’ve already entered a mindset in which easy ethical judgments become unconvincing and shallow. Our sympathies are effectively split; we’re either on nobody’s side or on everyone’s, and maybe it’s a little bit of both.

Needless to say, perhaps, this tricky transference would not be possible without the presence of a consummate actor in the title role, and Scott fits the bill beyond expectation. Though at first he reads as a bit old for the character, that notion quickly disperses – indeed, his weathered features bespeak the effects of a hard-knock life, the kind that makes a person willing to do anything to break free. More crucially, the unmistakable authenticity of his inner life is communicated with exquisite precision, engaging our empathy even as we recoil from the Machiavellian logic that guides him, and the clear conflict between his not-so-hidden feelings for Dickie and the agenda to which he has committed is made all the more stark by the ring of queer truth that underpins the performance. It’s a tour-de-force turn by an actor whose skills become more breathtaking with each subsequent role.

Fanning, whose equally adept performance provides a powerful counterpoint to Scott’s, is a strong contender for our sympathies, by virtue as much of the intelligence she brings as the peril into which it will eventually put her, and Flynn’s Dickie wears the weight and damage of his upper class status like a chain he can never quite break, making us dread the seemingly inevitable fate that awaits him even as we subliminally sign on to Ripley’s endgame with a sense of guilty (but unapologetic) satisfaction. Also notable is nonbinary actor Eliot Summers (child of former Police frontman Sting), who brings another level of queer identity into the narrative as another old acquaintance of Dickie’s that throws an unwelcome wrench into the works of Ripley’s plan.

Based on its first two episodes, “Ripley” certainly lives up to the anticipation that naturally awaits any adaptation of a high-profile story, and reasserts the queerness of an author who boldly pushed boundaries as far as censors of her time would allow. That’s more than enough to warrant staying with it until the end – and, if audience numbers warrant a renewal, through additional installments that might chronicle the less well-known escapades spun in Highsmith’s sequels. What cinches the deal, though, is the masterful performance that takes centerstage, which represents yet another escalation – and well-deserved triumph – in the rise of the talented Mr. Scott.

Movies

‘Love Lies Bleeding’ delivers retro lesbian thrills

A skillful blend of campy bold strokes and a spirit of rebellion

This month’s movies have been shaded with an awful lot of “noir.”

Not only that, but a surprising number of these movies – more accurately described as “neo-noir” to distinguish them from the formative black-and-white classics in this murkiest of all genres – are also very queer. We’ve seen Ethan Coen’s Tarantino-esque darkly comic lesbian road trip “Drive-Away Dolls” and the UK drag queen revenge drama “Femme”; now, from sophomore director Rose Glass (“Saint Maud”) comes “Love Lies Bleeding,” which might be queerest of the bunch so far.

It might be the “noir”-est, too; though there are a lot of vagaries around the characteristics that are required for applying that label, one of the most essential qualities is surely a morally ambiguous story. And morality can’t get much more ambiguous than it is in this retro-nostalgic throwback tale set on the fringes of the Albuquerque underworld of 1989. That’s where Lou (Kristen Stewart) has been for her entire life, and where she continues to stay – working as the manager of a run-down gym – out of protective loyalty to her sister Beth (Jena Malone), despite a longtime estrangement from her father (Ed Harris) and a desire to distance herself from the shadowy family “business” that he runs.

Reclusive and guarded, she mostly avoids social interaction – until an aspiring bodybuilder named Jackie (Katy O’Brian) hitchhikes into town on her way to a championship competition in Las Vegas and in need of a place to crash. There’s an instant spark between them, which quickly leads to flaming passion. Unfortunately, it also leads to an incident of explosive violence which puts both of them not only into the crosshairs of Lou’s ruthless and powerful dad, but those of the law as well.

There’s no need to say more than that in terms of synopsis; in fact, it would be unfair to the film, which unfolds with an exquisitely slow burn before igniting into a climactic powder keg as satisfying as it is gripping, because so much of the thrill comes from the feeling of uneasy expectation it delivers through its gradual revelation of details. Even without knowing more, however, it’s clear that there’s a lot going on in “Love Lies Bleeding” that doesn’t quite line up with the comforting ethics of a black-and-white worldview – and that, of course, is what gives it the kind of unpredictable edge that makes it both a tautly engrossing thriller and a deliciously subversive saga of queer and feminine empowerment.

This latter quality is something it shares with movies like “Bound” – the 1996 debut feature by the Wachowskis, which pushed mainstream acceptance by presenting its lesbian protagonists in a realistic manner and refusing to frame them in the then-usual trope of “queer victimhood” – and elevates to a refreshingly contemporary tone while still reveling in homage to the stylistic flourishes of their era.

Indeed, Glass peppers her film with echoes from dozens from the past that so clearly provided inspiration in both its visuals and its themes; from the twisted duplicity of Clouzot’s “Les Diaboliques” to the chaotic irony of the Coens’ “Blood Simple,” from the slick-but-gritty nihilism of William Friedkin to the disquieting body horror of David Cronenberg and the transcendental surrealism of David Lynch, “Love Lies Bleeding” borrows liberally and unapologetically from an array of cinematic touchstones almost as exhaustive as the one employed by Greta Gerwig in “Barbie” – and, like Gerwig, manages to incorporate them all in a sort of “metasphere” that allows our recognition of them to enhance and inform her own piece. Far from coming off as derivative, the effect is something akin to a “mash-up” of iconic eighties and nineties films and genres that uses their easy familiarity to both pay open tribute and tickle our nostalgic fancy, even as they are deployed as the building blocks for something with a singular identity of its own.

If you think that all sounds a little campy, you’re not wrong; there’s a definite element of tongue-in-cheek self awareness that permeates it, and a deliberate will toward underscoring the grimness of its outward scenario with the sly satire of its subtext. That, after all, is something else it shares in common with many of the older films it draws upon, in which “coded” characters and plotlines often served as subtle lampoons of the absurdly conventional messaging being conveyed on the surface. Camp is one of the oldest weapons in the queer artist’s arsenal, and Glass wields it like a pro.

Yet while she might use it to undermine cliches and upend expectations, the director never lets it distract – for long, at any rate – from the deadly stakes of her story. With a tight, terse screenplay (penned by Glass alongside Weronika Tofilska) that patiently sets up the dominoes for us until we’re quivering in anticipation of their fall, “Bleeding” takes time to relish in the details – the quirks of its characters, the unspoken dynamics between them, the secrets they keep and the moments they choose to reveal them – while making sure every one of them serves to wind the tension tighter. The effort pays off in a series of escalating climaxes that we know are coming yet still manage to surprise, shock, and ultimately, thrill us.

Gorgeous cinematography from Ben Fordesman helps, as does a period-perfect Tangerine Dream-esque score by Clint Mansell, but in such a character-driven film as this one, it’s always the actors who are most crucial to selling the director’s vision. In this case, Stewart and O’Brian are the linchpins, delivering a pair of deeply realized performances and a sultry-yet-sweet chemistry that wins us over almost before it does their characters. Both shine, with Stewart’s growth as an actor continuing to stretch her beyond her “Twilight” years and O’Brian’s earthy femininity bringing a welcome – and provocative – layer of gender ambiguity to the mix.

Backing them up are fine supporting turns from Malone and Anna Baryshnikov, whose hypnotically oddball performance as a clingy admirer who complicates Lou’s newfound romance is a highlight – as is Dave Franco’s simultaneously hilarious and repellant performance in a role it’s best we let you discover for yourself. Finally, though, it’s veteran screen baddie Harris who dominates, filling us with the kind of irrepressible dread that the most memorable movie villains always inspire – all while sporting a set of over-the-top hair extensions that immediately (and intentionally, we’d like to think) call to mind Richard O’Brien’s Riff-Raff in “The Rocky Horror Picture Show.”

Because of its skillful blend of such campy bold strokes and a genuine spirit of righteous rebellion that makes even its most broadly ridiculous moments cut with both sides of their satirical blade, we find “Bleeding” to be a new addition to an ever-growing canon of “essential” queer movies – with the disclaimer that some of its “weirder” moments might leave some viewers a bit perplexed, and those with a low tolerance to “gratuitous” violence and uninhibited sex scenes will likely want to skip it.

If, on the other hand, those things are a “plus” when deciding what to watch, then this is the movie for you.

-

LGBTQ Non-Profit Organizations5 days ago

LGBTQ Non-Profit Organizations5 days agoDay of [no] silence, a call to speak out against anti-LGBTQ+ hate

-

Africa2 days ago

Africa2 days agoCongolese lawmaker introduces anti-homosexuality bill

-

Colorado4 days ago

Colorado4 days agoFive transgender, nonbinary ICE detainees allege mistreatment at Colo. detention center

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoFirst lady warns Trump is ‘dangerous to the LGBTQ community’ at HRC event