Movies

Deadly 1973 hate crime recalled in new documentary

‘Upstairs Inferno’ screens Tuesday at Library of Congress

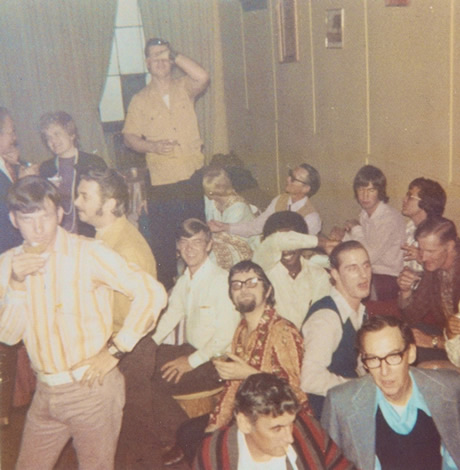

Patrons at the UpStairs Lounge. (Photo by Johnny Townsend; courtesy Camina Entertainment)

‘Upstairs Inferno’ screening

Thursday, Feb. 16

Noon-1:30 p.m.

Library of Congress

Pickford Theater (third floor of the James Madison Building)

Free

Tell your boss you’re taking a long lunch on Thursday. On Feb. 16, the Library of Congress will host the D.C. premiere of “Upstairs Inferno,” a powerful new documentary about a nearly forgotten piece of LGBT history, the tragic fire at the UpStairs Lounge in New Orleans in 1973.

The movie will screen at noon in the Pickford Theatre in the James Madison Building. Openly gay director Robert Camina will be on hand to discuss the film.

This is Camina’s second full-length feature, and his second film to be honored by the Library of Congress. His previous movie, “Raid of the Rainbow Lounge,” screened there in 2014. The acclaimed movie chronicled a controversial raid on a gay bar in Fort Worth, Texas in 2009.

“Raid” was a hit on the festival circuit and a chance encounter at a screening gave Camina the inspiration for this movie. Camina met David Golden, who told him about the fire and became a producer of the new movie. Before the Pulse Massacre in Orlando last June, the New Orleans arson was the deadliest known attack on a gay club in American LGBT history.

On June 24, 1973, someone deliberately set fire to a gay bar in New Orleans, killing 32 people. There was a primary suspect, but he was never arrested.

The tragedy was met with callous indifference by local officials, including the police, Mayor Maurice Landrieu, Governor Edwin Edwards and, most notably Archbishop Philip Michael Hannan who refused to hold a memorial service for the victims of the fire.

“I was shocked,” Camina says. “I had never heard of it. This was a benchmark moment in LGBT history. This was up there with Stonewall but nobody had heard about it. I thought that needed to change.”

A Texas native, Camina began by researching gay life in the Big Easy in 1973.

“People often think that New Orleans was much more liberal. That’s what I thought going in,” he says. “But it was pointed out to me that the French Quarter may be more liberal, but while the French Quarter is in New Orleans, New Orleans is not the French Quarter. The city is a microcosm for the South. It was difficult to live your life openly.”

Camina also began tracking down survivors. That was a challenge.

“The fire happened in 1973,” Camina says, “so even the youngest of the patrons were now in their late 50s or early 60s. There was the AIDS crisis, so we lost a lot of people who had a direct recollection of the fire. Then you add in Hurricane Katrina, archival material was destroyed and people were scattered.”

The first interview Camina filmed for the documentary was the Rev. Troy Perry, founder of the Metropolitan Community Church. Since several members of the New Orleans MCC were killed in the fire, including two members of the clergy, Perry came to the city to help his congregants and the community deal with the aftermath.

“The crew and I were in tears hearing him speak,” Camina says. “I love hearing him talk. That’s powerful history.”

The last person Camina interviewed on film was the legendary New Orleans drag performer Regina Adams, whose lover Reggie Adams died in the fire. Regina met Reggie at the UpStairs Lounge, one of the few places in the city that would welcome a gay interracial couple.

“They had a lot of obstacles but they loved each other immensely,” Camina says. “They were together at the UpStairs Lounge on the night of the fire. They realized they had left their wallets at home. Regina left to go around the corner to pick up her wallet. In the few moments that passed, that’s when the fire happened. She returned to find the bar in flames and she didn’t know what had happened to Reggie until she went to the hospital that night. It’s a story of true love.”

Camina notes that he reached out to both Adams and Perry after the Pulse Massacre last June. All three were horrified to see history repeat itself.

That sense of history is why Camina cares so much about “Upstairs Inferno,” especially in the current political climate.

“As more and more alternative facts pop up, we have to share the real facts, the real history,” he says. “We can’t go back to the horrible level of callousness that was displayed by the police and the church at the time of the tragedy. We need to remember our history and to honor the memory of those who perished. We can look to the past and draw on the strength of those who came before us.”

Director Robert L. Camina, left, and narrator Christopher Rice. (Photo courtesy Camina Entertainment)

Movies

After 25 years, a forgotten queer classic reemerges in 4K glory

Screwball rom-com ‘I Think I Do’ finds new appreciation

In 2024, with queer-themed entertainment available on demand via any number of streaming services, it’s sometimes easy to forget that such content was once very hard to find.

It wasn’t all that long ago, really. Even in the post-Stonewall ‘70s and ‘80s, movies or shows – especially those in the mainstream – that dared to feature queer characters, much less tell their stories, were branded from the outset as “controversial.” It has been a difficult, winding road to bring on-screen queer storytelling into the light of day – despite the outrage and protest from bigots that, depressingly, still continues to rear its ugly head against any effort to normalize queer existence in the wider culture.

There’s still a long way to go, of course, but it’s important to acknowledge how far we’ve come – and to recognize the efforts of those who have fought against the tide to pave the way. After all, progress doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and if not for the queer artists who have hustled to bring their projects to fruition over the years, we would still be getting queer-coded characters as comedy relief or tragic victims from an industry bent on protecting its bottom line by playing to the middle, instead of the (mostly) authentic queer-friendly narratives that grace our screens today.

The list of such queer storytellers includes names that have become familiar over the years, pioneers of the “Queer New Wave” of the ‘90s like Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, Gregg Araki, or Bruce LaBruce, whose work at various levels of the indie and “underground” queer cinema movement attracted enough attention – and, inevitably, notoriety – to make at least their names familiar to most audiences within the community today.

But for every “Poison” or “The Living End” or “Hustler White,” there are dozens of other queer films from the era; mostly screened at LGBTQ film festivals like LA’s Outfest or San Francisco’s Frameline, they might have experienced a flurry of interest and the occasional accolade, or even a brief commercial release on a handful of screens, before slipping away into fading memory. In the days before streaming, the options were limited for such titles; home video distribution was a costly proposition, especially when there was no guarantee of a built-in audience, so most of them disappeared into a kind of cinematic limbo – from which, thankfully, they are beginning to be rediscovered.

Consider, for instance, “I Think I Do,” the 1998 screwball romantic comedy by writer/director Brian Sloan that was screened – in a newly restored 4K print undertaken by Strand Releasing – in Brooklyn as the Closing Night Selection of NewFest’s “Queering the Canon” series. It’s a film that features the late trans actor and activist Alexis Arquette in a starring, pre-transition role, as well as now-mature gay heartthrob Tuc Watkins and out queer actor Guillermo Diaz in supporting turns, but for over two decades has been considered as little more than a footnote in the filmographies of these and the other performers in its ensemble cast. It deserves to be seen as much more than that, and thanks to a resurgence of interest in the queer cinema renaissance from younger film buffs in the community, it’s finally getting that chance.

Set among a circle of friends and classmates at Washington, D.C.’s George Washington University, it’s a comedic – yet heartfelt and nuanced – story of love left unrequited and unresolved between two roommates, openly gay Bob (Arquette) and seemingly straight Brendan (Christian Maelen), whose relationship in college comes to an ugly and humiliating end at a Valentine’s Day party before graduation. A few years later, the gang is reunited for the wedding of Carol (Luna Lauren Vélez) and Matt (Jamie Harrold), who have been a couple since the old days. Bob, now a TV writer engaged to a handsome soap opera star (Watkins) is the “maid” of honor, while old gal pals Beth (Maddie Corman) and Sarah (Marianne Hagan), show up to fill out the bridal party and pursue their own romantic interests. When another old friend, Eric (Diaz), shows up with Brendan unexpectedly in tow, it sparks a behind-the-scenes scenario for the events of the wedding, in which Bob is once again thrust into his old crush’s orbit and confronted with lingering feelings that might put his current romance into question – especially since the years between appear to have led Brendan to a new understanding about his own sexuality.

In many ways, it’s a film with the unmistakable stamp of its time and provenance, a low-budget affair shot at least partly under borderline “guerilla filmmaking” conditions and marked by a certain “collegiate” sensibility that results in more than a few instances of overly clever dialogue and a storytelling agenda that is perhaps a bit too heavily packed. Yet at the same time, these rough edges give it a raw, DIY quality that not only makes any perceived sloppiness forgivable, but provides a kind of “outsider” vibe that it wears like a badge of honor. Add to this a collection of likable performances – including Arquette, in a winning turn that gets us easily invested in the story, and Maelen, whose DeNiro-ish looks and barely concealed sensitivity make him swoon-worthy while cementing the palpable chemistry between them – and Sloan’s 25-year-old blend of classic Hollywood rom-com and raunchy ‘90s sex farce reveals itself to be a charming, wiser-than-expected piece of entertainment, with an admirable amount of compassion and empathy for even its most stereotypical characters – like Watkins’ soap star, a walking trope of vainglorious celebrity made more fully human than appearances would suggest by the actor’s sensitive, emotionally intelligent performance – that leaves no doubt its heart is in the right place.

Sloan, remarking about it today, confirms that his intention was always to make a movie that was more than just frothy fluff. “While the film seems like a glossy rom-com, I always intended an underlying message about the gay couple being seen as equals to the straight couple getting married,” he says. “ And the movie is also set in Washington to underline the point.”

He also feels a sense of gratitude for what he calls an “increased interest from millennials and Gen Z in these [classic queer indie] films, many of which they are surprised to hear about from that time especially the comedies.” Indeed, it was a pair of screenings with Queer Cinema Archive that “garnered a lot of interest from their followers,” and “helped to convince my distributor to bring the film back” after being unavailable for almost 10 years.

Mostly, however, he says “I feel very lucky that I got to make this film at that time and be a part of that movement, which signaled a sea change in the way LGBTQ characters were portrayed on screen.”

Now, thanks to Strand’s new 4K restoration, which will be available for VOD streaming on Amazon and Apple starting April 19, his film is about to be accessible to perhaps a larger audience than ever before.

Hopefully, it will open the door for the reappearance of other iconic-but-obscure classics of its era and help make it possible for a whole new generation to discover them.

Movies

Trans filmmaker queers comic book genre with ‘People’s Joker’

Alternative ‘Batman’ universe a medium for mythologized autobiography

It might come as a shock to some comic book fans, but the idea of super heroes and super villains has always been very queer. Think about it: the dramatic skin-tight costumes, the dual identities and secret lives, the inability to fit in or connect because you are distanced from the “normal” world by your powers – all the standard tropes that define this genre of pop culture myth-making are so rich with obviously queer-coded subtext that it seems ludicrous to think anyone could miss it.

This is not to claim that all superhero stories are really parables about being queer, but, if we’re being honest some of them feel more like it than others; an obvious example is “Batman,” whose domestic life with a teenage boy as his “ward” and close companion has been raising eyebrows since 1940. The campy 1960s TV series did nothing to distance the character from such associations – probably the opposite, in fact – and Warner Brothers’ popular ‘80s-’90s series of film adaptations solidified them even more by ending with gay filmmaker Joel Schumacher’s much-maligned “Batman and Robin,” starring George Clooney and Chris O’Donnell in costumes that highlighted their nipples, which is arguably still the queerest superhero movie ever made.

Or at least it was. That title might now have to be transferred to “The People’s Joker,” which – as it emphatically and repeatedly reminds us – is a parody in no way affiliated with DC’s iconic “Batman” franchise or any of its characters, even though writer, director and star Vera Drew begins it with a dedication to “Mom and Joel Schumacher.” Parody it may be, but that doesn’t keep it from also serving up lots of food for serious thought to chew on between the laughs.

Set in a sort of comics-inspired dystopian meta-America where unsanctioned comedy is illegal, it’s the story of a young, closeted transgender comic (Drew) who leaves her small town home to travel to Gotham City and audition for “GCB” – the official government-produced sketch comedy show. Unfortunately, she’s not a very good comic, and after a rocky start she decides to leave to form a new comedy troupe (labeled “anti-comedy” to skirt legality issues) along with penguin-ish new friend Oswald Cobblepot (Nathan Faustyn). They collect an assortment of misfit would-be comedians to join them, and after branding herself as “Joker the Harlequin,” our protagonist starts to find her groove – but it will take negotiating a relationship with trans “bad boy” Mr. J (Kane Distler), a confrontation with her self-absorbed and transphobic mother (Lynn Downey), and making a choice between playing by the rules or breaking them before she can fully transition into the militant comic activist she was always meant to be.

Told as a wildly whimsical, mixed media narrative that combines live action with a quirky CGI production design and multiple styles of animation (with different animators for each sequence), “People’s Joker” is by no means the kind of big-budget blockbuster we expect from a movie about a superhero — or in this case, supervillain, though the topsy-turvy context of the story more or less reverses that distinction — but it should be obvious from the synopsis above that’s not what Drew was going for, anyway. Instead, the Emmy-nominated former editor uses her loopy vision of an alternative “Batman” universe as the medium for a kind of mythologized autobiography expressing her own real-life journey, both toward embracing her trans identity and forging a maverick career path in an industry that discourages nonconformity, while also spoofing the absurdities of modern culture. Subverting familiar tropes, yet skillfully weaving together multiple threads from the “real” DC Universe she’s appropriated with the detailed savvy of a die-hard fangirl, it’s an accomplishment likely to impress her fellow comic book fans — even if they can’t quite get behind the gender politics or her presentation of Batman himself (an animated version voiced by Phil Braun) as a closeted gay right-wing demagogue and serial sexual abuser.

These elements, of course, are meant to be deliberately provocative. Drew, like her screen alter ego, is a confrontation comic at heart, bent on shaking up the dominant paradigm at every opportunity. Yet although she takes aim at the expected targets – the patriarchy, toxic masculinity, corporate hypocrisy, etc. – she is equally adept at scoring hits against things like draconian ideals of political correctness and weaponized “cancel culture”, which are deployed with extreme prejudice from idealogues on both sides of the ideological divide. This means she might be risking the alienation of an audience which might otherwise be fully in her corner – but it also provides the ring of unbiased personal truth that keeps the movie from sliding into propaganda and elevates it, like “Barbie”, to the level of absurdist allegory.

Because ultimately, of course, the point of “People’s Joker” has little to do with the politics and social constructs it skewers along the way; at its core, it’s about the real human things that resonate with all of us, regardless of gender, sexuality, ideology, or even political parties: the need to feel loved, to feel supported, and most of all, to be fully actualized. That means the real heart of the film beats in the central thread of its troubled connection between mother and daughter, superbly rendered in both Drew and Downey’s performances, and it’s there that Joker is finally able to break free of her own self-imposed restrictions and simply “be” who she is.

Other performances deserve mention, too, such as Faustyn’s weirdly lovable “Penguin” stand-in and Outsider multi-hyphenate artist David Leibe Hart as Ra’s al Ghul – a seminal “Batman” villain here reimagined as a veteran comic that serves as a kind of Obi-Wan Kenobi figure in Joker’s quest. In the end, though, it’s Drew’s show from top to bottom, a showcase for not only her acting skills, which are enhanced by the obvious intelligence (including the emotional kind) she brings to the table, but her considerable talents as a writer, director, and editor.

For some viewers, admittedly, the low-budget vibe of this crowd-funded film might create an obstacle to appreciating the cleverness and artistic vision behind it, though Drew leans into the limitations to find remarkably creative ways to convey what she wants with the means she has at her disposal. Others, obviously, will have bigger problems with it than that. Indeed, the film, which debuted at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, was withdrawn from competition there and pulled from additional festival screenings after alleged corporate bullying (presumably from Warner Brothers, which owns the film rights to the Batman franchise) pressured Drew into holding it back. Clearly, concern over blowback from conservative fans – who would likely never see the film anyway – was enough to warrant strong arm techniques from nervous execs. Nevertheless, “The People’s Joker” made its first American appearance at LA’s Outfest in 2023, and is now receiving a rollout theatrical release that started on April 5 in New York, and continues this week in Los Angeles, with Washington DC and other cities to follow on April 12 and beyond.

If you’re in one of the places where it plays, we say it’s more than worth making the effort. If you’re not, never fear. A VOD/streaming release is sure to come soon.

Movies

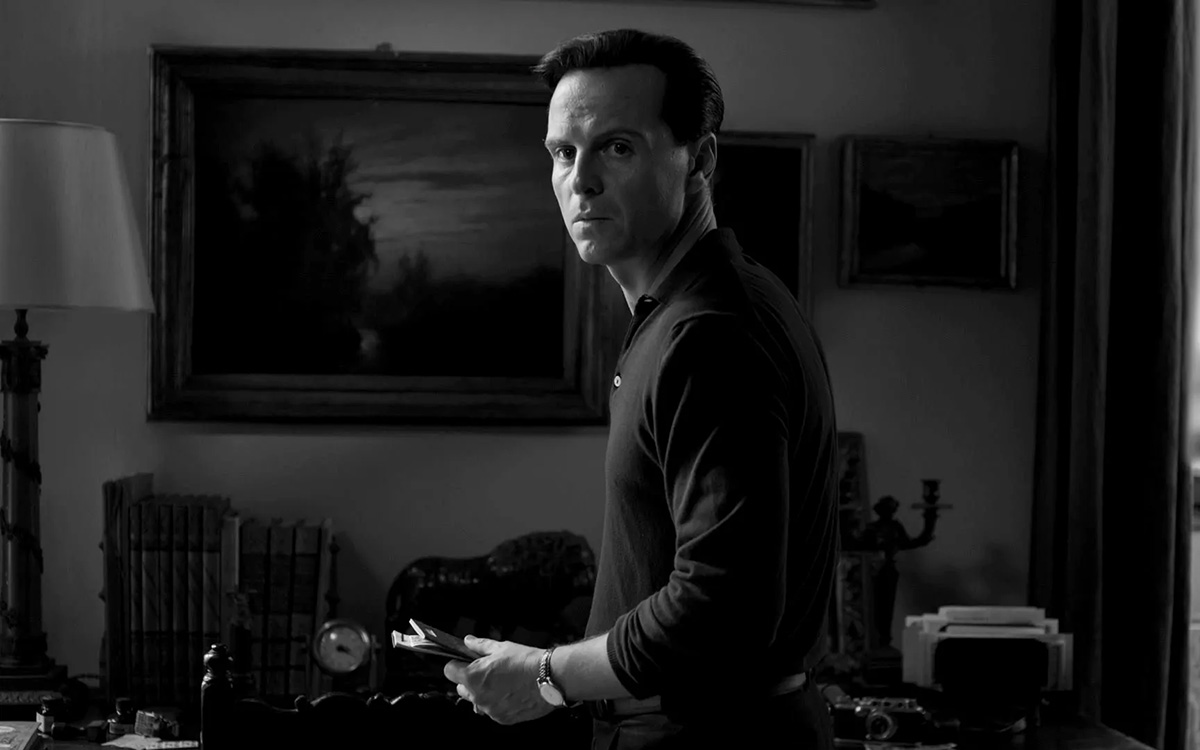

Star turn makes excellent ‘Ripley’ a showcase for Andrew Scott

Reasserting the queerness of an author who boldly pushed boundaries

There’s something about an anti-hero that appeals to us all. Why else would so many of our greatest stories revolve around a character whose behavior goes against everything we’ve been raised to believe is right?

Actually, that question probably answers itself. For many of us, the things we are raised to accept about life in the human world often feel less acceptable once we’ve gone through a few years of adult experience, which tends to put us at odds with the so-called “norms” of conformity. Naturally, this can be frustrating from time to time – and while that might not be enough to make us go “rogue” without regard law or ethics, it’s certainly sufficient to fuel our guilty fantasies.

That, along with the literary skills of Patricia Highsmith, the queer novelist who created him, is why the character of Tom Ripley has been engrossing us in various forms for nearly 75 years. The eponymous anti-hero of “The Talented Mr. Ripley” (originally published in 1955) went on to feature in three additional books by Highsmith, and was subsequently brought to life in multiple small-and-big-screen incarnations, perhaps most prominently by Matt Damon in Anthony Minghella’s 1999 film adaptation. These versions managed to skirt the book’s obvious queer subtext, but queer audiences recognized it anyway. Now, thanks to creator, writer, and director Steve Zaillian, Highsmith’s starry-eyed sociopath has returned in an eight-episode series – which pares the title down to the short-but-evocative “Ripley” – that debuts on Netflix April 4, and portrays his adventures with an eye toward honoring Highsmith’s intent while delivering the kind of up-front queerness that the author could never have dreamed of accomplishing in her heyday.

Not that this “Ripley” is exactly “out and proud,” though the actor who plays him – Andrew Scott (“All of Us Strangers”) – certainly is. The acclaimed Irish thespian brings his own queerness to the table in illuminating a character whose survival depends on never calling attention to himself – and though the series moves the action ahead a few years to1960, it’s still a world where any hint of “deviance” is likely to draw suspicion. That’s the last thing Tom Ripley needs; he’s a con artist, the mid-20th-century equivalent of modern-day “phishing” scammers, grifting gullible marks from his squalid, one-room New York City apartment. He’s good at what he does, an anonymous figure hiding in a sea of strangers – but when a wealthy shipping magnate tracks him down with a request for help and the offer of an all-expenses-paid excursion to Italy, he sees it as an opportunity to change his life for the better.

That opportunity, as it turns out, involves a barely remembered college acquaintance named Dickie (Johnny Flynn), whose post-graduation trip to Europe has become a years-long vacation on the Mediterranean coast from which his father – Ripley’s surprise benefactor – would like him to return. Sent on a mission to convince his old schoolmate to go home, he is instead spellbound by the idyllic seaside setting and opulent lifestyle that surrounds him – and also by Dickie himself. He ingratiates himself into the young man’s life, winning his sympathies despite some initial awkwardness. Not so easily persuaded is Dickie’s girlfriend, Marge (Dakota Fanning), whose lingering distrust must be overcome if Ripley is to enact his new master plan to claim Dickie’s life of expatriate luxury as his own.

Thanks to its source’s relative familiarity, “Ripley” makes no effort to hide the fact that its anti-hero is a shady guy; we see from the start that he’s a liar and an opportunist. What Zaillian manages to do, unlike others who have adapted the novel, is move past a clinical focus on Ripley’s psychology to give us a less prosaic – and therefore more complex – interpretation of the character. Much of this comes from a script that echoes Highsmith’s hard-boiled style by framing the story (and its protagonist) in a shadowy, amoral universe, enhanced by the stylish black-and-white treatment delivered by Robert Elswit’s cinematography, which leans into both the paradigm-challenging Euro “art cinema” from the period of its setting and the gritty chiaroscuro contrasts of film noir, setting up an instinctual understanding that this narrative, like its visuals, is composed entirely in shades of gray.

In the show’s engrossing first episode, this is a particularly effective hook, style coupling with context to underscore the bleakness of Ripley’s daily routine in New York, which is no less soul-crushing, perhaps, than the more lawful ones into which most of us are locked. Though we see that he’s a predator, it’s hard not to relate to his struggle, and by the time we get to the next chapter and meet Dickie and Marge, we’ve already entered a mindset in which easy ethical judgments become unconvincing and shallow. Our sympathies are effectively split; we’re either on nobody’s side or on everyone’s, and maybe it’s a little bit of both.

Needless to say, perhaps, this tricky transference would not be possible without the presence of a consummate actor in the title role, and Scott fits the bill beyond expectation. Though at first he reads as a bit old for the character, that notion quickly disperses – indeed, his weathered features bespeak the effects of a hard-knock life, the kind that makes a person willing to do anything to break free. More crucially, the unmistakable authenticity of his inner life is communicated with exquisite precision, engaging our empathy even as we recoil from the Machiavellian logic that guides him, and the clear conflict between his not-so-hidden feelings for Dickie and the agenda to which he has committed is made all the more stark by the ring of queer truth that underpins the performance. It’s a tour-de-force turn by an actor whose skills become more breathtaking with each subsequent role.

Fanning, whose equally adept performance provides a powerful counterpoint to Scott’s, is a strong contender for our sympathies, by virtue as much of the intelligence she brings as the peril into which it will eventually put her, and Flynn’s Dickie wears the weight and damage of his upper class status like a chain he can never quite break, making us dread the seemingly inevitable fate that awaits him even as we subliminally sign on to Ripley’s endgame with a sense of guilty (but unapologetic) satisfaction. Also notable is nonbinary actor Eliot Summers (child of former Police frontman Sting), who brings another level of queer identity into the narrative as another old acquaintance of Dickie’s that throws an unwelcome wrench into the works of Ripley’s plan.

Based on its first two episodes, “Ripley” certainly lives up to the anticipation that naturally awaits any adaptation of a high-profile story, and reasserts the queerness of an author who boldly pushed boundaries as far as censors of her time would allow. That’s more than enough to warrant staying with it until the end – and, if audience numbers warrant a renewal, through additional installments that might chronicle the less well-known escapades spun in Highsmith’s sequels. What cinches the deal, though, is the masterful performance that takes centerstage, which represents yet another escalation – and well-deserved triumph – in the rise of the talented Mr. Scott.

-

Africa3 days ago

Africa3 days agoCongolese lawmaker introduces anti-homosexuality bill

-

World4 days ago

World4 days agoOut in the World: LGBTQ news from Europe and Asia

-

District of Columbia3 days ago

District of Columbia3 days agoReenactment of first gay rights picket at White House set for April 17

-

Africa3 days ago

Africa3 days agoUgandan activists appeal ruling that upheld Anti-Homosexuality Act