National

After 39 years in ministry, Ga. bishop comes out

Swilley urges dialogue between gays, Christians

For Church in the Now’s Bishop Jim Swilley and Debye Swilley, the decision to divorce so Jim could live openly as a gay man is ‘a real love story.’ (Photo courtesy of CITN)

Bishop Jim Swilley founded Church in the Now, the massive, non-denominational congregation in Conyers, in 1985. But as the church grew over 25 years, and throughout his almost four decades of ministry, Swilley struggled with a secret that he hid from his congregation.

“I am approaching my 39th year in ministry — All I have ever done is preach the gospel,” Swilley told his congregation in an emotional sermon last month, noting that his parents tell stories of him preaching while still in diapers.

“There are two things in my life that are an absolute: I did not ask for either one of them, both of them were imposed upon me, I had no control over either of them,” Swilley said.

“One was the call of God in my life … the other thing, and I wouldn’t have known what to call it at the time, is my sexual orientation. I know a lot of straight people think that orientation is a choice, but I want to tell you that it definitely is not,” he said.

Swilley discounted rumors that he was cheating on his wife, who sat in the audience nodding her support, thanked his children and parents, and said that he was motivated to speak up by the recent rash of gay youth suicides, and by ongoing hate crimes targeting gay people.

“I can only hope that you hear me out and you hear me with an open mind,” Swilley said then.

The video of Swilley’s Oct. 13 coming out speech has gone viral with more than 50,000 views in three weeks. Jim Swilley, Debye Swilley and their son Judah Swilley spoke with the Georgia Voice about the experience.

GA Voice: Debye, people who watched that video really want to know if you support Jim. Can you speak to that?

Debye Swilley: I look at this as a real love story. I’ve always loved Jim and we learned to build a life around his sexual orientation. We built an incredible life together. We love each other and are best friends.

In March of 2009, it hit me that I was no longer a blessing to Jim. I was handicapping him. I was doing him a disservice by keeping him from growing because I was keeping him from being who he was. When I realized that I was hurting Jim more than helping him, that hurt me. I came to a place where I knew that I was no longer the best for him.

Jim Swilley: She came to me and said, “I think it’s time that you are able to walk in the way that you direct people. You tell people that God loves them just as they are and that God has a purpose for them just as they are and you don’t give that same break to yourself.”

I told her, “If we were going to still work together [in ministry], you realize that you’re outing me. People will look at us and wonder if we’re that fine with each other, why don’t we just stay married?”

Debye: I told Jim Earl, “I will do anything that you want for me to do. If you want me to be the crazy woman who freaked out or let people think that I had an affair, I really don’t care what anybody says about me. If you don’t ever want to come out with this, it’s your truth. I just can’t do it anymore. I will not be in agreement with us not being everything that we’re supposed to be. Just know that I will never hurt you and I will always protect you.”

Jim: The church had a lot of questions. People still saw us together and there was speculation about why we were divorcing. There was enough buzz about it that I tried to address it at our church’s 25th anniversary. Somehow, the word got out into the community that I came out that day. We kept trying to decide what to do. Should I leave it? Should I say more? I was talking all around it.

The real thing that made me go ahead with it was that two-week period when those five or six gay teen suicides happened. I decided that I couldn’t not talk about this. I was just going to put it out there and whatever happens would happen. If I lost the ministry, I’d deal with that. I wasn’t afraid. I just knew it was right.

Voice: What has been the general response from the public and from your church membership?

Jim: In one week, I gained over 1,000 Facebook friends. I’ve heard from Hong Kong, Japan, London, South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria… one story after another from people who say, “Oh my God. I feel like you totally told my story.” I’ve heard from other pastors who’ve come out or pastors who are still in the closet, afraid to come out. I’ve heard from teenagers. For every negative one that I get, there’ll be a hundred that are loving and affirming. I hear it over and over: “You saved my life.”

Voice: Judah, what have you observed about people’s reactions to your dad sharing his truth?

Judah Swilley: Thank God that most of it has been supportive. Unfortunately, we’ve heard from closed-minded religious people that see things a different way. The crazy thing is that the people who have extreme religious beliefs and they bring out different scriptures and try to pick and choose them to make their point. You can’t just pick one thing and take it out of context.

You know, Leviticus says all kinds of crazy things. …

Debye: What people might not understand is that Jim carried this fear of rejection with him that is so deep that it would come out in the way that he would minister. I always knew in my heart that if he just loved himself just the way that he was and if he embraced his humanity, the divine part would be exponential.

Voice: Bishop Swilley, what do you want to tell the gay community in Atlanta?

Jim: One of Jesus’ last words on the cross was “Father, forgive them. For they know not what they do.”

What I would to say to the gay community is that Proverbs says that life is in the power of the tongue and the only thing that I know to do is to continue to communicate. I understand why so many gay people left the church. I totally get it. I understand why so many of them don’t believe in God. I want to be somewhat of a bridge builder or repairer of the breach.

What I would say to gay Christians is to continue to dialogue if you can.

U.S. Military/Pentagon

4th Circuit rules against discharged service members with HIV

Judges overturned lower court ruling

A federal appeals court on Wednesday reversed a lower court ruling that struck down the Pentagon’s ban on people with HIV enlisting in the military.

The conservative three-judge panel on the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned a 2024 ruling that had declared the Defense Department and Army policies barring all people living with HIV from military service unconstitutional.

The 4th Circuit, which covers Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia, held that the military has a “rational basis” for maintaining medical standards that categorically exclude people living with HIV from enlisting, even those with undetectable viral loads — meaning their viral levels are so low that they cannot transmit the virus and can perform all duties without health limitations.

This decision could have implications for other federal circuits dealing with HIV discrimination cases, as well as for nationwide military policy.

The case, Wilkins v. Hegseth, was filed in November 2022 by Lambda Legal and other HIV advocacy groups on behalf of three individual plaintiffs who could not enlist or re-enlist based on their HIV status, as well as the organizational plaintiff Minority Veterans of America.

The plaintiffs include a transgender woman who was honorably discharged from the Army for being HIV-positive, a gay man who was in the Georgia National Guard but cannot join the Army, and a cisgender woman who cannot enlist in the Army because she has HIV, along with the advocacy organization Minority Veterans of America.

Isaiah Wilkins, the gay man, was separated from the Army Reserves and disenrolled from the U.S. Military Academy Preparatory School after testing positive for HIV. His legal counsel argued that the military’s policy violates his equal protection rights under the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

In August 2024, a U.S. District Court sided with Wilkins, forcing the military to remove the policy barring all people living with HIV from joining the U.S. Armed Services. The court cited that this policy — and ones like it that discriminate based on HIV status — are “irrational, arbitrary, and capricious” and “contribute to the ongoing stigma surrounding HIV-positive individuals while actively hampering the military’s own recruitment goals.”

The Pentagon appealed the decision, seeking to reinstate the ban, and succeeded with Wednesday’s court ruling.

Judge Paul V. Niemeyer, one of the three-judge panel nominated to the 4th Circuit by President George H. W. Bush, wrote in his judicial opinion that the military is “a specialized society separate from civilian society,” and that the military’s “professional judgments in this case [are] reasonably related to its military mission,” and thus “we conclude that the plaintiffs’ claims fail as a matter of law.”

“We are deeply disappointed that the 4th Circuit has chosen to uphold discrimination over medical reality,” said Gregory Nevins, senior counsel and employment fairness project director for Lambda Legal. “Modern science has unequivocally shown that HIV is a chronic, treatable condition. People with undetectable viral loads can deploy anywhere, perform all duties without limitation, and pose no transmission risk to others. This ruling ignores decades of medical advancement and the proven ability of people living with HIV to serve with distinction.”

“As both the 4th Circuit and the district court previously held, deference to the military does not extend to irrational decision-making,” said Scott Schoettes, who argued the case on appeal. “Today, servicemembers living with HIV are performing all kinds of roles in the military and are fully deployable into combat. Denying others the opportunity to join their ranks is just as irrational as the military’s former policy.”

New York

Lawsuit to restore Stonewall Pride flag filed

Lambda Legal, Washington Litigation Group brought case in federal court

Lambda Legal and Washington Litigation Group filed a lawsuit on Tuesday, challenging the Trump-Vance administration’s removal of the Pride flag from the Stonewall National Monument in New York earlier this month.

The suit, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, asks the court to rule the removal of the Pride flag at the Stonewall National Monument is unconstitutional under the Administrative Procedures Act — and demands it be restored.

The National Park Service issued a memorandum on Jan. 21 restricting the flags that are allowed to fly at National Parks. The directive was signed by Trump-appointed National Park Service Acting Director Jessica Bowron.

“Current Department of the Interior policy provides that the National Park Service may only fly the U.S. flag, Department of the Interior flags, and the Prisoner of War/Missing in Action flag on flagpoles and public display points,” the letter from the National Park Service reads. “The policy allows limited exceptions, permitting non-agency flags when they serve an official purpose.”

That “official purpose” is the grounds on which Lambda Legal and the Washington Litigation Group are hoping a judge will agree with them — that the Pride flag at the Stonewall National Monument, the birthplace of LGBTQ rights movement in the U.S., is justified to fly there.

The plaintiffs include the Gilbert Baker Foundation, Charles Beal, Village Preservation, and Equality New York.

The defendants include Interior Secretary Doug Burgum; Bowron; and Amy Sebring, the Superintendent of Manhattan Sites for the National Park Service.

“The government’s decision is deeply disturbing and is just the latest example of the Trump administration targeting the LGBTQ+ community. The Park Service’s policies permit flying flags that provide historical context at monuments,” said Alexander Kristofcak, a lawyer with the Washington Litigation Group, which is lead counsel for plaintiffs. “That is precisely what the Pride flag does. It provides important context for a monument that honors a watershed moment in LGBTQ+ history. At best, the government misread its regulations. At worst, the government singled out the LGBTQ+ community. Either way, its actions are unlawful.”

“Stonewall is the birthplace of the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement,” said Beal, the president of the Gilbert Baker Foundation. The foundation’s mission is to protect and extend the legacy of Gilbert Baker, the creator of the Pride flag.

“The Pride flag is recognized globally as a symbol of hope and liberation for the LGBTQ+ community, whose efforts and resistance define this monument. Removing it would, in fact, erase its history and the voices Stonewall honors,” Beal added.

The APA was first enacted in 1946 following President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s creation of multiple new government agencies under the New Deal. As these agencies began to find their footing, Congress grew increasingly worried that the expanding powers these autonomous federal agencies possessed might grow too large without regulation.

The 79th Congress passed legislation to minimize the scope of these new agencies — and to give them guardrails for their work. In the APA, there are four outlined goals: 1) to require agencies to keep the public informed of their organization, procedures, and rules; 2) to provide for public participation in the rule-making process, for instance through public commenting; 3) to establish uniform standards for the conduct of formal rule-making and adjudication; and 4) to define the scope of judicial review.

In layman’s terms, the APA was designed “to avoid dictatorship and central planning,” as George Shepherd wrote in the Northwestern Law Review in 1996, explaining its function.

Lambda Legal and the Washington Litigation Group are arguing that not only is the flag justified to fly at the Stonewall National Monument, making the directive obsolete, but also that the National Park Service violated the APA by bypassing the second element outlined in the law.

“The Pride flag at the Stonewall National Monument honors the history of the fight for LGBTQ+ liberation. It is an integral part of the story this site was created to tell,” said Lambda Legal Chief Legal Advocacy Officer Douglas F. Curtis in a statement. “Its removal continues the Trump administration’s disregard for what the law actually requires in their endless campaign to target our community for erasure and we will not let it stand.”

The Washington Blade reached out to the NPS for comment, and received no response.

Massachusetts

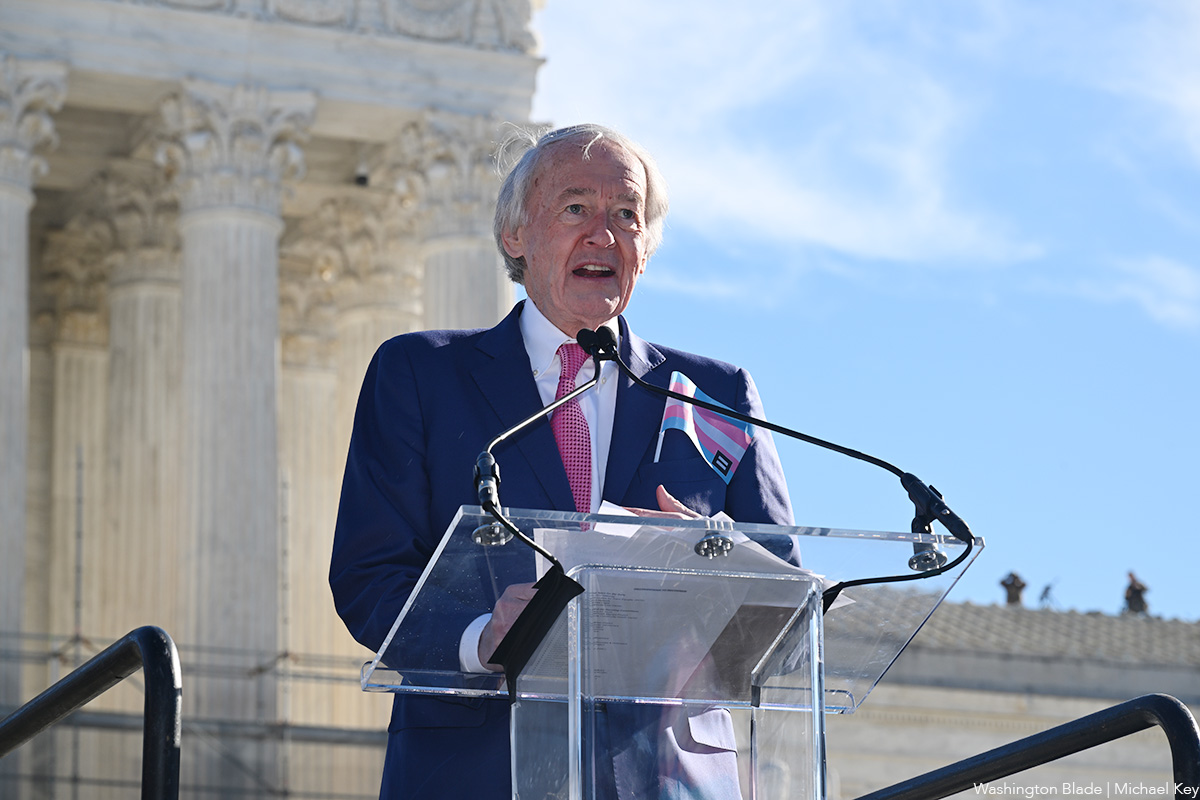

EXCLUSIVE: Markey says transgender rights fight is ‘next frontier’

Mass. senator, 79, running for re-election

For more than half a century, U.S. Sen. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) has built a career around the idea that government can — and should — expand rights rather than restrict them. From pushing for environmental protections to consumer safeguards and civil liberties, the Massachusetts Democrat has long aligned himself with progressive causes.

In this political moment, as transgender Americans face a wave of federal and state-level attacks, Markey says this fight in particular demands urgent attention.

The Washington Blade spoke with Markey on Tuesday to discuss his reintroduction of the Trans Bill of Rights, his long record on LGBTQ rights, and his reelection campaign — a campaign he frames not simply as a bid for another term, but as part of a broader struggle over the direction of American democracy.

Markey’s political career spans more than five decades.

From 1973 to 1976, he served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, representing the 16th Middlesex District, which includes the Boston suburbs of Malden and Melrose, as well as the 26th Middlesex District.

In 1976, he successfully ran for Congress, winning the Democratic primary and defeating Republican Richard Daly in the general election by a 77-18 percent margin. He went on to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives for nearly four decades, from 1976 until 2013.

Markey in 2013 ran in the special election to fill an open Senate seat after John Kerry became secretary of state in the Obama-Biden administration. Markey defeated Republican Gabriel E. Gomez and completed the remaining 17 months of Kerry’s term. Markey took office on July 16, 2013, and has represented Massachusetts in the U.S. Senate ever since.

Over the years, Markey has built a reputation as a progressive Democrat focused on human rights. From environmental protection and consumer advocacy to civil liberties, he has consistently pushed for an expansive view of constitutional protections. In the Senate, he co-authored the Green New Deal, has advocated for Medicare for All, and has broadly championed civil rights. His committee work has included leadership roles on Senate Foreign Relations Committee and the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee.

Now, amid what he describes as escalating federal attacks on trans Americans, Markey said the reintroduction of the Trans Bill of Rights is not only urgent, but necessary for thousands of Americans simply trying to live their lives.

“The first day Donald Trump was in office, he began a relentless assault on the rights of transgender and nonbinary people,” Markey told the Blade. “It started with Executive Order 14168 ‘Defending women from gender ideology extremism and restoring biological truth to the federal government.’ That executive order mandates that federal agencies define gender as an unchangeable male/female binary determined by sex assigned at birth or conception.”

He argued that the executive action coincided with a sweeping legislative push in Republican-controlled statehouses.

“Last year, we saw over 1,000 anti trans bills across 49 states and the federal government were introduced. In January of 2026, to today, we’ve already seen 689 bills introduced,” he said. “The trans community needs to know there are allies who are willing to stand up for them and affirmatively declare that trans people deserve all of the rights to fully participate in public life like everyone else — so Trump and MAGA Republicans have tried hard over the last year to legislate all of these, all of these restrictions.”

Markey said the updated version of the Trans Bill of Rights is designed as a direct response to what he views as an increasingly aggressive posture from the Trump-Vance administration and its GOP congressional allies. He emphasized that the legislation reflects new threats that have emerged since the bill’s original introduction.

In order to respond to those developments, Markey worked with U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) to draft a revised version that would more comprehensively codify protections for trans Americans under federal law.

“What we’ve added to the legislation is this is all new,” he explained, describing how these proposed protections would fit into all facets of trans Americans’ lives. “This year’s version of it that Congresswoman Jayapal and I drafted, there’s an anti-trans bias in the immigration system should be eliminated.”

“Providers of gender affirming care should be protected from specious consumer and medical fraud accusations. The sexual and gender minority research office at the National Institutes of Health should be reopened and remain operational,” he continued. “Military discharges or transgender and nonbinary veterans and reclassification of discharge status should be reviewed. Housing assignments for transgender and nonbinary people in government custody should be based on their safety needs and involuntary, solitary or affirmative administrative confinement of a transgender or nonbinary individual because of their gender identity should be prohibited, so without it, all of those additional protections, and that’s Just to respond to the to the ever increasingly aggressive posture which Donald Trump and his mega Republicans are taking towards the transgender.”

The scope of the bill, he argued, reflects the breadth of challenges trans Americans face — from immigration and health care access to military service and incarceration conditions. In his view, the legislation is both a substantive policy response and a moral declaration.

On whether the bill can pass in the current Congress, Markey acknowledged the political hardships but insisted the effort itself carries as much significance as the bill’s success.

“Well, Republicans have become the party of capitulation, not courage,” Markey said. “We need Republicans of courage to stand up to Donald Trump and his hateful attacks. But amid the relentless attacks on the rights and lives of transgender people across the country by Trump and MAGA Republicans, it is critical to show the community that they have allies in Congress — the Trans Bill of Rights is an affirmative declaration that federal lawmakers believe trans rights are human eights and the trans people have the right to fully participate in public life, just like everyone else.”

Even if the legislation does not advance in this congress, Markey said, it establishes a framework for future action.

“It is very important that Congresswoman Jayapal and I introduce this legislation as a benchmark for what it is that we are going to be fighting for, not just this year, but next year,” he said when asked if the bill stood a legitimate chance of passing the federal legislative office when margins are so tight. “After we win the House and Senate to create a brand new, you know, floor for what we have to pass as legislation … We can give permanent protections.”

He framed the bill as groundwork for a future Congress in which Democrats regain control of both chambers, creating what he described as a necessary roadblock to what he views as the Trump-Vance administration’s increasingly restrictive agenda.

Markey also placed the current political climate within the longer arc of LGBTQ history and activism.

When asked how LGBTQ Americans should respond to the removal of the Pride flag from the Stonewall National Monument — the first national monument dedicated to recognizing the LGBTQ rights movement — Markey was unwavering.

“My message from Stonewall to today is that there has been an ongoing battle to change the way in which our country responds to the needs of the LGBTQ and more specifically the transgender community,” he said. “When they seek to take down symbols of progress, we have to raise our voices.”

“We can’t agonize,” Markey stressed. “We have to organize in order to ensure that that community understands, and believes that we have their back and that we’re not going away — and that ultimately we will prevail.”

Markey added, “That this hatefully picketed White House is going to continue to demonize the transgender community for political gain, and they just have to know that there’s going to be an active, energetic resistance, that that is going to be there in the Senate and across our country.”

Pam Bondi ‘is clearly part’ of Epstein cover up

Beyond LGBTQ issues, Markey also addressed controversy surrounding Attorney General Pam Bondi and the handling of the Epstein files, sharply criticizing the administration’s response to congressional inquiries.

“Well, Pam Bondi is clearly part of a cover up,” Markey said when asked about the attorney general’s testimony to Congress amid growing bipartisan outrage over the way the White House has handled the release of the Epstein files. “She is clearly part of a whitewash which is taking place in the Trump administration … According to the New York Times, Trump has been mentioned 38,000 times in the [Epstein] files which have been released thus far. There are still 3 million more pages that have yet to be released. So this is clearly a cover up. Bondi was nothing more than disgraceful in the way in which she was responding to our questions.”

“I think in many ways, she worsened the position of the Trump administration by the willful ignoring of the central questions which were being asked by the committee,” he added.

‘I am as energized as I have ever been’

As he campaigns for reelection, Markey said the stakes extend beyond any single issue or piece of legislation. He framed his candidacy as part of a broader fight for democracy and constitutional protections — and one that makes him, as a 79-year-old, feel more capable and spirited than ever.

“Well, I am as energized as I have ever been,” he said. “Donald Trump is bringing out the Malden in me. My father was a truck driver in Malden, Mass., and I have had the opportunity of becoming a United States senator, and in this fight, I am looking ahead and leading the way, affirming rights for the trans community, showing up to defend their rights when they are threatened from this administration.”

He continued, reiterating his commitment not only to the trans community but to a future in which progressive and proactive pushes for expanded rights are seen, heard, and actualized.

“Our democracy is under threat from Donald Trump and MAGA Republicans who are trying to roll back everything we fought for and threaten everything we stand for in Massachusetts, and their corruption, their greed, their hate, just make me want to fight harder.”

When asked why Massachusetts voters should reelect him, he said his age and experience as a 79-year-old are assets rather than hindrances.

“That’s exactly what I’m doing and what I’m focused upon, traveling across the state, showing up for the families of Massachusetts, and I’m focused on the fights of today and the future to ensure that people have access to affordable health care, to clean air, clean water, the ability to pay for everyday necessities like energy and groceries.”

“I just don’t talk about progress. I deliver it,” he added. “There’s more to deliver for the people of Massachusetts and across this country, and I’m not stopping now as energized as I’ve ever been, and a focus on the future, and that future includes ensuring that the transgender community receives all of the protections of the United States Constitution that every American is entitled to, and that is the next frontier, and we have to continue to fight to make that promise a reality for that beleaguered community that Trump is deliberately targeting.”

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoTrump falsely links trans people to terrorism

-

Virginia5 days ago

Virginia5 days agoFellow lawmakers praise Adam Ebbin after Va. Senate farewell address

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoLGBTQ activists mourn the Rev. Jesse Jackson

-

Massachusetts4 days ago

Massachusetts4 days agoEXCLUSIVE: Markey says transgender rights fight is ‘next frontier’