Health

The graying of AIDS: living longer with HIV

‘None of us expected to live this long’

D.C. resident John Klenert signed up for a National Institutes of Health-funded AIDS study at Johns Hopkins University in 1984. The Centers for Disease Control reported the first cases of what became known as AIDS three years earlier, but some of Klenert’s friends had already passed away from the virus by the time the research project had begun.

“We figured if there was going to be a cure that we would be the first ones to volunteer to get these tests,” he said.

Johns Hopkins researchers in 1986 screened the first blood samples that Klenert and other study participants had given once scientists discovered the virus that causes AIDS. “For me, the first blood I had given was positive,” he said. “I would have been shocked had I turned out to be negative.”

Older people with HIV will be the focus of a July 25 forum at the International AIDS Conference. Panelists will include Ricardo Jimenez of the Ecuadorian Red Cross, Carolyn Massey of Older Women Embracing Life, Inc., Wojciech Tomczynski of the Polish Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS Association and Ruth Waryaro of Help Age International in Uganda. Doctor Kevin Fenton of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Stephen Karpiak and Mark Brennan-Ing of AIDS Community Research Initiative of America’s Center on HIV and Aging and New York University College of Nursing are among those who are scheduled to speak during the plenary.

The CDC estimates that 10.8 percent of the roughly 50,000 new HIV infections that occur each year in the United States are among those older than 50. It further reports that 16.7 percent of new diagnoses in 2009 were among this demographic, with half of them also having AIDS. Federal health officials predict that half of people with HIV in the United States by 2015 will be older than 50.

ACRIA, the New York-based Gay Men’s Health Crisis and Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders co-organized the forum as part of what SAGE Senior Director of Public Policy Robert Espinoza described to the Blade as a need to increase visibility around HIV-related aging issues.

“We feel it’s an important conversation because there are so many people who are aging with HIV and AIDS,” he told the Blade.

Increased access to treatment in the United States and other developed countries has allowed more people with HIV to live longer. The arrival of more widely available anti-retroviral drugs in the mid-1990s has also contributed to this trend.

“If you were 35 in 1990 and you made it to the mid to late 90s and got on protease inhibitors, there’s a good chance you’re still alive today and you’d be above 50,” said ACRIA executive director Daniel Tietz. “And that’s the reality.”

Older people with HIV face unique challenges

Johns Hopkins and CDC researchers noted earlier this year that older people with HIV are more likely to suffer higher rates of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, non-AIDS related cancers and other chronic illnesses. Klenert, who is now 63, has had a brain tumor removed and an operation to repair an aneurysm over the last 30 years. He said that his neurologist and cardiologist both said that his HIV status did not contribute to either of these conditions.

“There are many folks who age into this — they’ve had HIV for a while, their HIV is reasonably well-managed,” said Tietz. “It’s their other things. It’s their hypertension, the diabetes, the heart disease that are posing challenges in terms of management.”

This population also faces the same hurdles that service providers maintain older LGBT people without the virus routinely face. These include a lack of health care, financial insecurity and social isolation, but a person’s HIV status can acerbate these problems.

“The LGBT community in general is not great on aging issues; they tend to be more youth centered,” said Espinoza. “We find that a lot of older adults with HIV are often looking just for both the caregiving support they need to manage their health and remain optimistic and maintain their emotional health, but they are looking for community.”

He and other service providers stressed that stigmas associated with HIV and sexuality can dissuade older people from discussing their sexual health with doctors and other health care providers.

“If you’re not talking openly to people who manage your health then it’s going to then prevent the kind of services you need to age successfully,” said Espinoza, further stressing that many health care providers don’t even provide HIV tests to their older patients who could have just become sexually active after leaving a relationship or getting divorced. “We’re dealing with constituents who have been living with HIV and AIDS for years. We’re dealing with constituents who have been infected for years, but just got diagnosed, which often means the illness has progressed more in their bodies. And then we’re also dealing with constituents who just became infected and are trying to assimilate to both the emotional and health issues related to their infection.”

The New York City Council has funded ACRIA’s efforts to bolster HIV prevention efforts among older New Yorkers with HIV. The National Institutes of Health’s Office of AIDS Research has also established a working group to study the virus’ impact on older people.

“I don’t think government officials have put this on their radar screen as much as they should,” said Espinoza. “As the demographic really begins growing in the next two years, we’re going to see more questions from aging providers and health care professionals about what it means to appropriately serve older adults with HIV and engage them in their facilities or in their long-term care facilities. And with that, I’m hoping that government officials will also increase their attention and increase the funding for that kind of programmatic prevention.”

Seeking to increase visibility

Those who advocate on behalf of older people with HIV further stress that lack of visibility remains a problem.

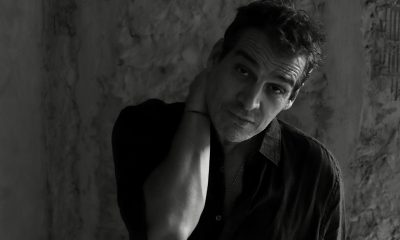

The Graying of AIDS project profiles older people with the virus as a follow-up to photojournalist Katja Heinemann’s eponymous photo essay that “Time” published in 2006 to mark the epidemic’s 25th anniversary. D.C. resident Ronald Johnson, vice president of policy and advocacy for AIDS United, is among the 11 people that Heinemann and Naomi Schegloff profile in photographs and short videos.

Schegloff, who works in the public health field, told the Blade that she “very much appreciated” what she described as “frank discussions” about sexuality that took place with many of those whom she and Heinemann profiled. Discrimination, a desire for companionship and a general lack of information about HIV are also common themes.

“A lot of older adults have not been on the market in the last 30 years, or have barely been on the market in the last 30 years,” said Schegloff. “If they’ve been with a partner — married or otherwise — for a long time, they may or may not have dated at a time when HIV was something we knew about. If for them condoms are something that you use to avoid getting pregnant and they’re heterosexual and they’re a woman and they’ve gone through menopause, they’re not worried about that anymore. And it used to be that for people of a certain generation, the worst thing you could get through sex as one person told us in an interview is something you can take penicillin for now. They weren’t necessarily thinking about this thing [HIV] as being relevant to them.”

Heinemann and Schegloff plan to photograph and interview those from the United States and around the world who are interested in participating in their project during the Global Village at the International AIDS Conference. They will upload images, interview excerpts and other content to an online exhibition during the five-day gathering.

“For us as a visual project and a documentary project, we’re hoping to really put a face to this that will be a little bit of a wakeup call where you don’t just read the statistic,” said Heinemann. “But you’re also able to see oh yeah wait a minute, this is not just Bill in Chicago and Ronald in D.C. This is also a person from Tanzania; this is also a person from Russia or someone from India.”

Klenert, a former Victory Fund and Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation board member, also reflected upon those with HIV who continue to grow older.

“I’d like to think that people in my age group are hopeful as well as surprised,” he said in response to a question about the changes he has seen since he tested positive. “I’m guessing that most of us didn’t think that we would live this long. There’s that old greeting card [that says] had I lived this long I would have taken better care of us. Back when we were in our 30s — or late 30s — none of us expected to live this long because back then the mortality rate was almost 100 percent.”

Health

Housewives head to Capitol Hill to promote PrEP coverage

Bravo’s Real Housewives stars to lobby lawmakers for expanded PrEP access.

Stars from Bravo’s hit franchise “The Real Housewives” are heading to Capitol Hill next week to advocate for expanded access to HIV prevention and treatment.

On March 18, several well-known cast members — including NeNe Leakes, Phaedra Parks, Candiace Dillard Bassett, Erika Jayne, Luann de Lesseps, Melissa Gorga, and Marysol Patton — will travel to D.C. to participate in an advocacy event aimed at increasing awareness and coverage for pre-exposure prophylaxis, commonly known as PrEP.

The event, dubbed “Housewives on the Hill,” is being organized by MISTR, the nation’s largest telehealth platform focused on sexual health. The group’s founder and CEO, Tristan Schukraft, will join the reality television stars as they meet with lawmakers and legislative staff to discuss the importance of maintaining and expanding access to HIV prevention tools.

PrEP is a medication regimen that can, if taken properly, reduce the risk of contracting HIV through sex by up to 99 percent according to public health officials. Advocates say wider access to the medication — including through insurance coverage and telehealth services — is critical to reducing new HIV infections across the United States.

During their day on Capitol Hill, the Housewives are expected to meet with members of Congress and participate in conversations about federal policies affecting HIV prevention and treatment. Organizers say the reality stars will also share personal reflections about the continued impact of HIV on communities across the country and the importance of keeping prevention resources accessible.

The “Housewives on the Hill” event aims to use the cultural influence of the Bravo stars to spotlight HIV prevention efforts and encourage lawmakers to protect and expand access to lifesaving medication and treatment options. Organizers say the goal is simple: ensure that more Americans can access the tools they need to prevent HIV and maintain their sexual health.

Health

Too afraid to leave home: ICE’s toll on Latino HIV care

Heightened immigration enforcement in Minneapolis is disrupting treatment

Uncloseted Media published this article on March 3.

This story was produced in collaboration with Rewire News Group, a nonprofit publication reporting on reproductive and sexual health, rights and justice.

This story was produced with the support of MISTR, a telehealth platform offering free online access to PrEP, DoxyPEP, STI testing, Hepatitis C testing and treatment and long-term HIV care across the U.S. MISTR did not have any editorial input into the content of this story.

By SAM DONNDELINGER and CAMERON OAKES | For two weeks, Albé Sanchez didn’t leave their house in South Minneapolis.

“[I was] forced into survival mode,” Sanchez told Uncloseted Media and Rewire News Group (RNG). “I felt like there was an invisible wall [to the outside world] that I couldn’t cross unless I really wanted to put myself in a place where there was a chance that I might not be able to come back.”

Queer and Mexican American, Sanchez was afraid of being targeted by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement presence in their neighborhood, even though they are a U.S. citizen.

“Every day is a risk,” they say, adding that even if they have paperwork, if they fit the profile, they are a target, making it scary to go even to work or the grocery store.

Sanchez, a 30-year-old sexual health care educator, has been taking oral PrEP, the daily preventive medication for HIV, for over a decade. But the mounting stress of ICE raids has made it harder to keep up with dosing.

“A missed dose here and there pushed me to make the appointment [for something more sustainable],” they say.

Sanchez says they felt like somebody would have their back at their local clinic. It was only a 10-minute drive from where they worked, they knew its staff from previous visits and community outreach, and they could count on finding Spanish-speaking staff and providers of Latino heritage. But not everybody has had that same experience accessing care.

Since ICE’s Operation Metro Surge began in early December, an increasing number of Latino patients in Minnesota are delaying or canceling what can be lifesaving care for the prevention and treatment of HIV.

These findings are particularly alarming for Latino communities, who, as of 2023, are 72 percent more likely than the general U.S. population to be diagnosed with HIV. And while overall infections have decreased, cases among Latinos increased by 24 percent between 2010 and 2022.

“I’m very concerned that there is going to be a sharp uptick in transmission,” says Alex Palacios, a community health specialist in the Minneapolis area.

In a January 2026 declaration as part of a lawsuit seeking to end Operation Metro Surge in the days following Renee Nicole Good’s killing, the commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Health said HIV testing among Latino populations has “dropped dramatically” and that “although grantee staff continue to go into the community to promote and provide testing, people are not showing up.”

Local clinics are reporting the same thing. The Aliveness Project, a community wellness center in Minneapolis specializing in HIV care, told Uncloseted Media and RNG they have seen more than a 50 percent decrease in new clients. The clinic serves a large number of Latino and undocumented clients, and while it usually sees 750 people walk through their door each week, according to providers, it reported seeing 100 fewer people each week since December.

Red Door, Minnesota’s largest STI and HIV clinic, has had a “modest uptick” in no-shows and missed appointments since December.

What happens when treatment stops

Today, there are multiple medications available that work to prevent HIV and dozens that treat it once a person tests positive. Many people who consistently take their medication have such low levels of the virus that they can’t transmit it through sex. But becoming undetectable requires patients to stay on their medication; otherwise, the virus replicates and mutates, weakening the immune system and increasing the risk of life-threatening infections.

“If patients aren’t on their medicines consistently, HIV can learn about the medication and become resistant to them. When this happens, the medicine will not work for the patient, and the new resistant virus could potentially be passed on to others,” says George Froehle, a physician assistant and provider at Aliveness Project. “Medication adherence is one of the most important aspects of HIV care.”

To maintain care and prevent dangerous, untreatable strains from spreading in Minnesota, providers at Aliveness Project have begun delivering medication to patients when possible, offering telehealth when they can, and pausing routine lab work to limit in-person appointments.

“The most important thing we can do from a public health perspective is to keep people undetectable so they don’t transmit HIV,” Froehle says, adding that providers in other cities targeted by ICE will need to make plans for missed injection visits, pivot to telehealth and prepare their teams for the “trauma that can occur.”

Sanchez understands the risks of inconsistent treatment, which is why they opted for the injectable preventative medication.

“I have a lot of risk [to HIV in my community],” Sanchez says. “With so much uncertainty about the future and whether HIV care will remain stable, I realized I couldn’t let this opportunity pass.”

But injectable HIV treatments are commonly dosed at two weeks to six months apart, and the medication must be administered in a clinic — a setting many patients are avoiding, according to providers.

“They have a two-week window” to get their shots, according to Froehle, who added that because patients are afraid to come in person, they have had to transition people off of their injectable HIV treatments. This has caused patients to return to oral HIV treatments without the testing they would normally receive had ICE not been in Minneapolis. “[Oral treatments] weren’t super successful [for these patients] to begin with and that’s why they were on injectables.”

Oral HIV medications, too, must be taken consistently to work. In response, providers have urged patients to have their pills with them at all times in case they get deported or detained.

The caution is not unfounded. Federal immigration facilities have a history of denying adequate medical care to people living with HIV, despite internal standards that require them to comply. Since 2025, at least two men living with HIV have been denied access to their medication in a Brooklyn jail, according to lawsuits obtained by THE CITY. One man said he was only given his medication after his lips broke open and he developed an open pustule on his leg. And in January 2025, another man died of HIV complications while in ICE custody in Arizona.

Beyond being detained without proper medication, patients are at risk of being deported to countries with limited access to HIV care, like Honduras and Venezuela, experts say.

“A lot of men [from Venezuela] told me they left because it wasn’t safe to be gay there and because they struggled to access HIV care,” says Froehle. “It’s a little heartbreaking to see new folks not only face the threat of deportation, but to places where they didn’t feel safe medically or identity-wise.”

“Some of these patients will die in their home country,” says Anna Person, the chair of the HIV Medicine Association. “It’s a death sentence.”

A ‘cascading disaster’

While ICE’s presence is threatening the infrastructure of HIV care that Minneapolis has built over decades, experts say there has always been a blind spot in HIV care for the city’s Latino community.

Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, executive director of the Institute for Policy Solutions at the Johns Hopkins University of Nursing, describes HIV in Latino communities as a “cascading disaster,” the result of years of compounding inequities.

“There’s been an invisible crisis among Latinos that hasn’t gotten traction,” he says. “The numbers have consistently gone up in terms of new infections, while nationally they’ve gone down. … That should be a big alarm.”

Numbers are rising because structural barriers and stigma are preventing Latinos from receiving care. A 2022 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that between 2018 and 2020, nearly 1 in 4 Hispanic people living with HIV reported experiencing discrimination in health care settings. Lack of representation among providers, language barriers and deep-rooted medical mistrust further complicate access to care, according to Guilamo-Ramos.

Beyond the medical system, stigma within Latino communities can be equally damaging. According to Human Rights Campaign data, more than 78 percent of Latino LGBTQ youth reported experiencing homophobia or transphobia within the Latino community in 2024.

Sanchez agrees that stigma and bias are already massive barriers to care, citing the strict gender norms and Catholic beliefs many Latino communities hold. They say ICE’s presence is threatening already delicate access to HIV care.

“This has caused so much damage to people,” Sanchez says. “Not being able to access your health care appointments is such a stab in the side. … Being able to navigate any of these things in normal circumstances already has so much difficulty to it.”

Palacios, who is Afro-Latine and living with HIV, says the heightened ICE presence is worsening barriers that have long undermined the Latino community’s access to HIV care.

“The horizon has always been stark and dim,” they say. “And this just feels like one more thing to address and to fight back against.”

Sliding backwards

Navigating HIV care is becoming more difficult across the board, as the federal government has decimated HIV funding, compromising decades of progress made in the fight against the virus since Donald Trump retook office just over a year ago.

In February 2026, three months into Operation Metro Surge, the Trump-Vance administration proposed slashing $600 million in HIV-related grants, targeting four blue states, including $42 million for Minnesota programs. A federal judge has temporarily blocked the cuts.

“This would completely decimate and gut all of our HIV prevention,” says Dylan Boyer, director of development at Aliveness Project. “That’s the reality that we live in.”

“We have all the tools, and yet we are staring down this rollback of infrastructure and research dollars, prevention efforts, treatment efforts, that are going to put us squarely back in the 1980s,” says Person, a national HIV expert who grew up in Minnesota. “[There] seems to be no other rationale for that besides cruelty, to be quite frank, since there’s no scientific reason for it.”

Repair and representation

Jenny Harding, director of advancement at a Minneapolis-area supportive housing program for people living with HIV, says that while ICE’s presence is lessening in the Twin Cities, the “damage is done.”

Person says that this mending will take time, especially between the medical community and patients, since HIV providers can have a “very fragile” relationship with their clients.

“It takes, sometimes, years to build that level of trust. And I do worry that folks are just going to say, ‘I don’t feel safe here anymore. The system does not have my best interest at heart, and I’m not coming back,’” she says. “This is not something that you can flip a switch and everything will go back to normal.”

“We need to hold our federal government accountable, particularly HHS, [and] we need to ensure that HIV funding remains intact,” Guilamo-Ramos says, adding that in order to lower rates of HIV in the Latino community, there should be more specialized efforts: such as bilingual and culturally aligned health care providers, community-based outreach programs co-located where risk is highest, trust-building initiatives to address medical mistrust, mobile clinics, and targeted programs to re-engage patients who have fallen out of care.

Aliveness Project’s patient numbers have increased in the last few weeks as the ICE operation has waned, but the clinic staff is keeping “a watchful eye” and is having “difficulty reaching folks who are understandably scared.”

“Our biggest focus right now is reconnecting with people through our outreach so no one has a lapse in their HIV medications or prevention care,” Boyer, of Aliveness Project, says.

For Sanchez, seeing providers who speak Spanish and are of Latin heritage at Aliveness Project built enough trust for them to reach out and make an appointment despite the risks. Sanchez feels optimistic about their new injectable prevention strategy with the support of their clinic.

“There’s many places where you can receive care here in the Twin Cities where you might not see your skin tone. … There’s still a lot of health care professionals that unfortunately carry bias. … Aliveness is the opposite of that,” they say. “Seeing that representation and knowing someone has that cultural context of how to meet you in moments of sensitivity, it’s crucial.”

District of Columbia

Trans activists arrested outside HHS headquarters in D.C.

Protesters demonstrated directive against gender-affirming care

Authorities on Tuesday arrested 24 activists outside the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services headquarters in D.C.

The Gender Liberation Movement, a national organization that uses direct action, media engagement, and policy advocacy to defend bodily autonomy and self-determination, organized the protest in which more than 50 activists participated. Organizers said the action was a response to changes in federal policy mandated by Executive Order 14187, titled “Protecting Children from Chemical and Surgical Mutilation.”

The order directs federal agencies and programs to work toward “significantly limiting youth access to gender-affirming care nationwide,” according to KFF, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that provides independent, fact-based information on national health issues. The executive order also includes claims about gender-affirming care and transgender youth that critics have described as misinformation.

Members of ACT UP NY and ACT UP Pittsburgh also participated in the demonstration, which took place on the final day of the public comment period for proposed federal rules that would restrict access to gender-affirming care.

Demonstrators blocked the building’s main entrance, holding a banner reading “HANDS OFF OUR ‘MONES,” while chanting, “HHS—RFK—TRANS YOUTH ARE NO DEBATE” and “NO HATE—NO FEAR—TRANS YOUTH ARE WELCOME HERE.”

“We want trans youth and their loving families to know that we see them, we cherish them, and we won’t let these attacks go on without a fight,” said GLM co-founder Raquel Willis. “We also want all Americans to understand that Trump, RFK, and their HHS won’t stop at trying to block care for trans youth — they’re coming for trans adults, for those who need treatment from insulin to SSRIs, and all those already failed by a broken health insurance system.”

“It is shameful and intentional that this administration is pitting communities against one another by weaponizing Medicaid funding to strip care from trans youth. This has nothing to do with protecting health and everything to do with political distraction,” added GLM co-founder Eliel Cruz. “They are targeting young people to deflect from their failure to deliver for working families across the country. Instead of restricting care, we should be expanding it. Healthcare is a human right, and it must be accessible to every person — without cost or exception.”

Despite HHS’s efforts to restrict gender-affirming care for trans youth, major medical associations — including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Endocrine Society — continue to regard such care as evidence-based treatment. Gender-affirming care can include psychotherapy, social support, and, when clinically appropriate, puberty blockers and hormone therapy.

The protest comes amid broader shifts in access to care nationwide.

NYU Langone Health recently announced it will stop providing transition-related medical care to minors and will no longer accept new patients into its Transgender Youth Health Program following President Donald Trump’s January 2025 executive order targeting trans healthcare.

-

Health4 days ago

Health4 days agoToo afraid to leave home: ICE’s toll on Latino HIV care

-

Movies4 days ago

Movies4 days agoIntense doc offers transcendent treatment of queer fetish pioneer

-

The White House3 days ago

The White House3 days agoTrump will refuse to sign voting bill without anti-trans provisions

-

Colombia4 days ago

Colombia4 days agoClaudia López wins primary in Colombian presidential race