Opinions

The state of HIV in Washington: 29 years later

From fear and despair to promising new treatments and hope

On April 4, 1983, AIDS entered the public arena of the District of Columbia.

On a Monday evening 29 years ago, Whitman-Walker held the first public forum on AIDS in D.C. At that time, Cabbage Patch dolls were a hit, people were watching M*A*S*H, and AIDS was destroying the gay male community. A panel of public health experts and advocates spoke to a full house at Lisner Auditorium of The George Washington University. The audience of predominantly gay men was driven to the forum after watching friends, lovers and colleagues die quickly and horribly from AIDS. And they were in a state of fear bordering on panic.

The forum that night probably did little to calm that fear. Think about what was happening in 1983. AIDS had only been recently named. The HIV virus had not been discovered yet. There was no test to see if someone was infected and there was no treatment. In fact, people were unsure if you could catch AIDS from a simple kiss. In short, there was almost no good news that night; only fear and despair for the future.

Today, on the eve of the 2012 International AIDS Conference, there is far more good news in the world of HIV/AIDS.

Since that forum in 1983, HIV testing has become standard operating procedure for many Americans, particularly those in groups at high risk for HIV, like gay or bisexual men. Successful treatments are keeping people with HIV healthy and alive for many years. And people are more knowledgeable about condom use and other safer sex practices.

Over the last few years, even more developments have brought new hope and optimism in the fight against HIV/AIDS, including the idea of using HIV medications to prevent HIV transmission, also known as “Treatment as Prevention.”

One of the best ways to reduce new HIV transmissions is by diagnosing people with HIV, getting them into care and on medications. These HIV medications can suppress the amount of virus in the person’s blood to very low levels, which make it much less likely for that person to transmit the virus. In fact, studies have shown successful treatment to reduce the risk of transmission by up to 96 percent. This same strategy is used to prevent the mother’s HIV from transmitting to the baby.

Another way HIV medications are used to reduce transmission is through HIV “post-exposure prophylaxis” or “PEP.” If a person has a needle stick at work or an unsafe sexual encounter they can take HIV medications for a month to prevent infection. This method is at least 80 percent effective if used within 72 hours of the potential exposure.

Recently, studies have shown HIV medications can be taken by individuals at high risk for HIV before they are exposed to the virus to protect them from infection. “Pre-exposure prophylaxis” or “PREP” is still undergoing clinical trials but seems to be very effective for certain populations at high risk for HIV, such as men who have sex with men and serodiscordant couples (where one partner has HIV and the other is HIV-negative).

All of these new “Treatment as Prevention” tools add to weapons in the fight against new HIV transmissions, but none are a magic bullet. Currently, in the District of Columbia, 70 percent of people diagnosed with HIV do not have a suppressed viral load. Why is this number so high? A large number of people in D.C. have HIV and do not know it. Others have been diagnosed with HIV but have not seen a doctor yet (often due to denial, stigma, etc.). And lastly, a good percentage of HIV-positive people on medication do not have a suppressed HIV viral load due to poor adherence to their medication regimen (often due to depression, addiction issues or competing priorities). We are lucky at Whitman-Walker to have comprehensive health care on site, including care teams, mental health practitioners, a pharmacy, and nurses that focus on patients’ barriers to care. Through this team model, 85 percent of our HIV patients on medications have a suppressed viral load.

Now that the health care community has more options in our fight against HIV, we have to figure out a comprehensive way to prevent new HIV transmissions from occurring. But the good news is that we are more knowledgeable about HIV transmission and there are more prevention options with known effectiveness.

So come join us in a Return to Lisner Auditorium on Tuesday, July 24, at 7 p.m. You will hear from leaders in the field that reducing the number of new HIV infections in Washington, D.C. is possible. You will learn about “Treatment as Prevention.” And we will all reflect on how far we have come in the past 29 years.

Dr. Ray Martins is chief medical officer of Whitman-Walker Health.

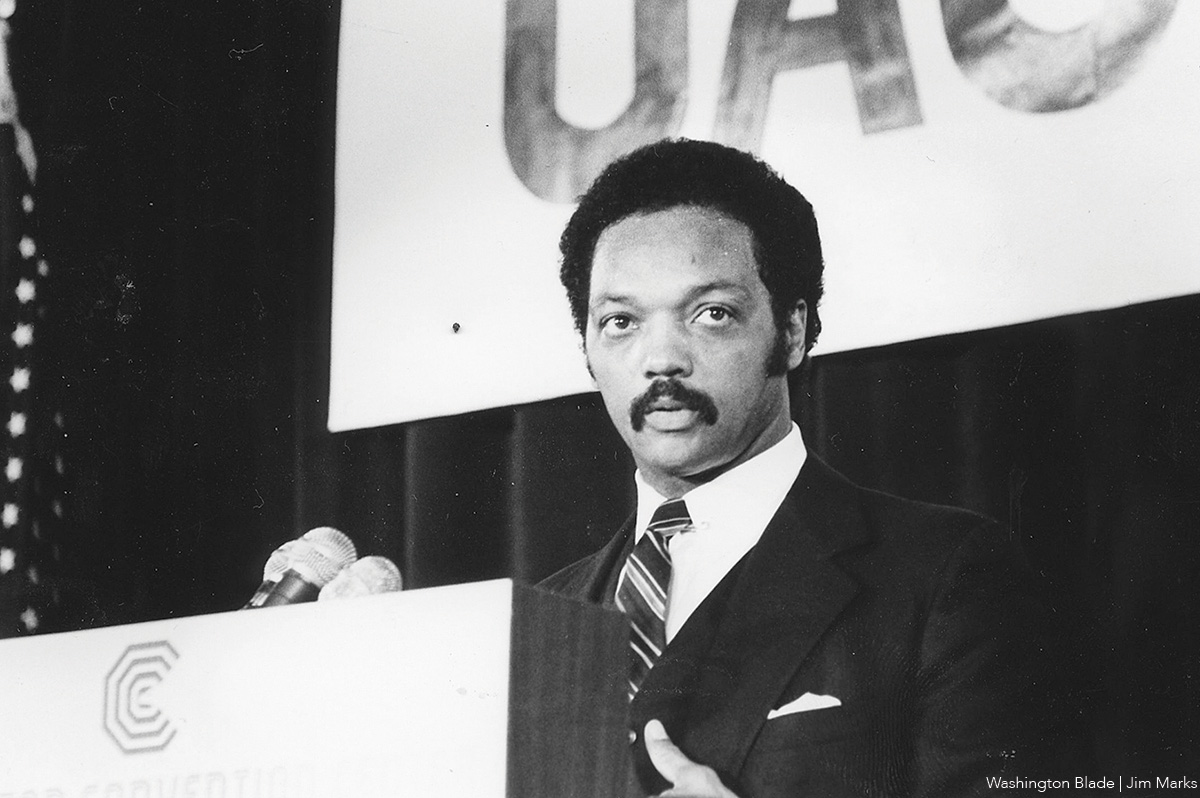

There is no question that Jesse Louis Jackson, Sr. had a significant impact on the civil rights movement, Democratic Party politics and D.C.’s struggle for statehood. After I heard of his death, I took some time to reflect on how our lives had intersected although I met him only once in person.

During the 1970s, sickle cell disease was a celebrated cause in the African-American community. Rev. Jackson was in the vanguard of that advocacy because he had the sickle cell trait. My mother had sickle cell disease and I have the trait. I responded to Rev. Jackson’s exhortation to be involved with fighting the disease and was blessed to have worked for seven years at the Howard University Center for Sickle Disease in its community outreach program.

In 1983, the March on Washington for Jobs, Peace & Freedom was held to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington. Local organizing committees called Coalitions of Conscience were formed to get people involved with the march. I attended the first meeting in D.C. and introduced a resolution that the 20th anniversary program held on the National Mall include a speaker representing the LGBT community. The resolution passed unanimously but the response from the chief organizer of the march, Rev. Walter Fauntroy, was that no such speaker would be permitted. Fauntroy was also the District of Columbia delegate to Congress. Three days before the march, four gay men – all D.C. residents, three of whom were Black – went to meet with Del. Fauntroy to discuss his opposition to having a LGBT speaker on the day of the march. He refused to meet with them and had them arrested. I was one of those arrested.

Our arrests made local and national news. While we were in jail, a conference call was held consisting of representatives of most of the major national civil rights leaders in the nation to discuss having an LGBT speaker at the march. Among those on that call were Coretta Scott King, Ralph Abernathy, Mayor Marion Barry, Dorothy Height; Reverends Joseph Lowery, Walter Fauntroy and Jesse Jackson. The decision was made to give three minutes to a speaker representing the LGBT community. The speaker was Audre Lorde, the African-American lesbian writer, poet, professor and civil rights activist. Jesse Jackson’s presence on that call was critical to her being chosen as a speaker.

In 1984, I was a volunteer in the Jesse Jackson for president campaign in his quest for the Democratic Party nomination. I, along with dozens of volunteers, boarded the bus that left from Union Temple Baptist Church to journey to Alabama to campaign for Rev. Jackson in that state’s primary. My involvement with Jackson’s D.C. campaign led me to visit the Players Lounge for the first time in order to get signatures for Jackson’s D.C. presidential delegate slate and to do voter registration.

Jackson did not win the Democratic presidential nomination in either his 1984 or 1988 campaigns. But his efforts along with Congresswoman Shirley Chisolm’s and Rev. Al Sharpton’s presidential campaigns paved the way for Barack Obama’s historic nomination and victory for president in 2008.

In 1990, Jesse Jackson was elected to be one of D.C.’s United States Senators or what is known as a “shadow senator.” He made it clear that D.C.’s struggle for statehood is not just a political issue but a salient civil and human rights issue. His involvement helped make D.C. statehood a national issue.

I cannot remember the exact year that I finally met Jesse Jackson in person but it was around the turn of the millennium. There was an event taking place in the Panorama Room at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Roman Catholic Church. Rev. Jackson was standing alone on the hill taking in the breathtaking view of D.C. I walked over, introduced myself and thanked him for what he had done for the D.C. statehood, LGBT rights, and the Democratic Party. Even though he was a major celebrity he gave me a hug as if we were longtime friends. It was a brief conversation but we both agreed to keep praying for a cure for sickle cell disease. That hope is still being kept alive.

Philip Pannell is a longtime Ward 8 community activist. Reach him at [email protected].

When we’re out with friends, we ask a question that sometimes surprises people: Are you on PrEP?

PrEP is a medication that reduces the risk of getting HIV by about 99 percent when taken as prescribed. We’re both on it. And we both talk about it openly because too many people in our communities still haven’t heard of it, can’t access it, or have been made to feel like asking for it says something about who they are.

It doesn’t. Taking PrEP is about taking control of your health. It’s that simple.

But getting there wasn’t simple for either of us. Our paths to PrEP looked different.

Del. Martinez learned this firsthand. When he asked his primary care doctor about PrEP, the response wasn’t medical — it was judgment. Instead of a prescription, he got a lecture. He had to leave Maryland entirely and go to Whitman-Walker in D.C. just to get basic preventive care. He serves on the Health Committee and sits on the public health subcommittee. Even he couldn’t access HIV prevention in his own state. That reality was soul-crushing, not just for him, but because he immediately thought about every person in his community who doesn’t have the resources to find another way.

Phillip came to PrEP through his work at FreeState Justice, where he was learning about HIV transmission rates and the gap in PrEP access for queer people of color. Black Marylanders account for 65 percent of new HIV diagnoses but only about 35 percent of PrEP users. Latino Marylanders account for nearly 19 percent of new diagnoses but fewer than 8 percent of PrEP users.

Seeing those numbers, he had to ask himself why he wasn’t on it. When he walked into Chase Brexton’s HIV Prevention clinic in Baltimore, the experience was easy and affirming, exactly what it should be for everyone. No judgment, just care. That’s the kind of experience every Marylander deserves.

A proposed bill would make it the standard in Maryland. HB 1114 would let people walk into their neighborhood pharmacy and access PrEP without waiting months for a doctor’s appointment, remove insurance barriers that slow things down, and connect them to ongoing care.

Our stories are not unusual. When we talk to friends about PrEP — and we do, regularly — we hear the same things. People who didn’t know about it. People who tried and gave up. People who assumed it wasn’t for them. People who couldn’t afford it or couldn’t find a provider. There’s still misinformation out there, and there’s still stigma. Among women in Maryland, most new HIV diagnoses come from heterosexual contact, but PrEP is still rarely part of the conversation from their doctors.

When we talk to our friends about PrEP, we lead with honesty. Here’s what it does, here’s what it costs, here’s where to go. We talk about the different options: daily pills or long-acting shots. Generic options are available, and in many cases, free. If you’re sexually active, it might be right for you. It’s not a morality question. It’s a health question.

We try to make it feel approachable, because it should be. We answer every question, because sometimes we’re the first person someone has had this conversation with. It’s a conversation between people who trust each other. And it works, but it can only go so far when the system itself is still in the way.

We have the medical tools to virtually end new HIV transmissions. What we need now are the policies to make sure everyone can reach them. At a time when the future of federal HIV prevention programs is under attack, Maryland has both the opportunity and the responsibility to lead.

We’re asking our friends to take charge of their health. We’re asking Maryland to make it possible.

If PrEP sounds right for you, talk to your provider. If you know someone who could benefit, share what you know. And if you want to see Maryland get this right, tell your legislators to support HB 1114.

State Del. Ashanti Martinez represents District 22 in Prince George’s County in the Maryland House of Delegates, where he serves as Majority Whip and sits on the Health Committee. Phillip Westry is the executive director of FreeState Justice, Maryland’s statewide LGBTQ+ advocacy organization.

Opinions

A dream: Democrats focus on candidates who can win

Defeating every Republican has to be the goal in 2026, 2028

I know this is just a dream, but I am a dreamer and continue to hope Democrats can get beyond Black or white, gay or straight, man or woman; to look at who can win in 2026, and then in 2028. It’s often said each election is the most consequential in our lifetime. The next two actually are.

The reality is without change; we face losing our democracy. We have a racist, sexist, homophobic, lying felon, in the White House. He has a Cabinet of vile incompetents, and a cadre of fascist advisers, controlling our government. They threaten our freedoms, and even our health. They think the military is theirs to use at will, without restrictions. Again, my dream for elections in 2026 and 2028, is we put our personal desires aside, for the good of the nation.

Everyone is being hurt by Trump. Black women being fired in huge numbers. Transgender people literally having their lives threatened. The LGBTQ community facing new threats. Civil rights are being undermined, and the Latino community across the country is targeted. Women are losing the right to control their bodies. Our voting rights are being threatened, and all this is happening with the consent of the Republican sycophants in Congress who are either in complete agreement with the felon, or threatened into submission by him, and his fascist cohorts. This is what we are facing in the next two election cycles as we try to take back our country. As the opposition party, we must first take back Congress in 2026. If we succeed, we must replicate that success as we work to reclaim the White House in 2028.

I believe we must all be represented in our elected officials. For years I felt comfortable looking at the equality issue in choosing a candidate, as even in the worst-case scenarios, when losing meant the election of the likes of a Richard Nixon or Ronald Reagan, I never believed my country’s existence was threatened. They, and others like them, may have been vile, but none professed wanting to be king. They didn’t go to court seeking full immunity for anything they did and getting it from judges they appointed.

I am a proud gay man but will not automatically vote for an LGBTQ candidate in the next elections. In 2024, I worked hard, and proudly, to see two strong Black women elected to the United States Senate. In the 2008 primary I was proud to stand with Hillary Clinton, then support Barack Obama when he won the nomination. In 2016, I again stood with Hillary. In 2020, I proudly supported Kamala Harris as vice president and then supported her for president in 2024.

Today, I am looking at the next two election cycles differently. I have written the only way to win back my country is to look at which Democrat can win in a particular race. I will support a Democrat committed to voting for the Democratic leadership in the House and the Senate, and in their state legislature, even if they don’t support fully everything I want. Because when Democrats win the leadership, they set the agenda. The Democratic platform has been about the same for many years. It stands for equality in every area. Have we accomplished all we stand for, clearly NO. Have we made progress, clearly YES.

In these upcoming elections each Democrat may win their race with a different set of issues at the forefront. I have suggested in the morning they go to the diners in their district, and in the evening to the bars, to find out what people are talking about, and concerned about. Then respond to that by running on those issues. If there is a primary, demand each candidate pledge to fully support the winner. Think about what is said about Democrats and Republicans, “Democrats fall in love; Republicans fall in line.” Well in the next two election cycles, Democrats need to fall in line with every Democrat on the ballot in the general election willing to say, “if elected I will vote for, and support, the Democratic leadership.”

If we don’t commit to doing that in the next two election cycles, we may actually not have future elections. It is the only way we can stop the felon, and his fascist government, from winning. Defeating every Republican in 2026 and 2028, has to be the goal for all who care about our country, and moving on to the next 250 years. Not winning is not an option.

Peter Rosenstein is a longtime LGBTQ rights and Democratic Party activist.

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoToo afraid to leave home: ICE’s toll on Latino HIV care

-

Colombia5 days ago

Colombia5 days agoClaudia López wins primary in Colombian presidential race

-

The White House4 days ago

The White House4 days agoTrump will refuse to sign voting bill without anti-trans provisions

-

Iran4 days ago

Iran4 days agoMan stuck in Lebanon as Iran war escalates