Theater

Channeling Wallace

The Arena Stage (1101 Sixth St., S.W) production runs through May 8th

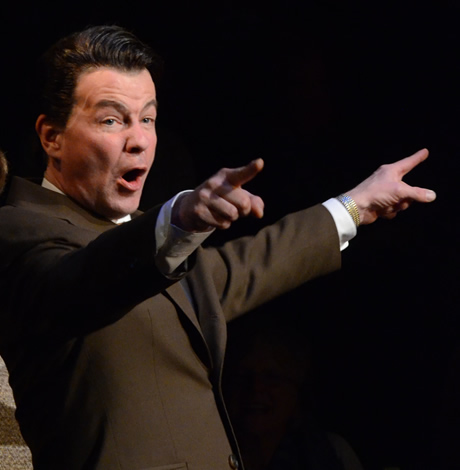

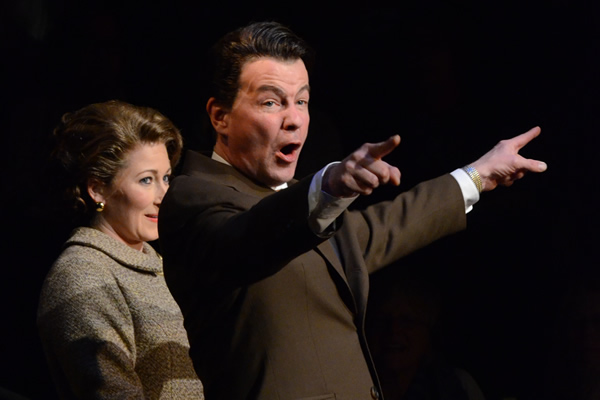

Cameron Folmar says ‘All the Way’ is about historical events that have eerily apt significance to modern life. (Photos courtesy Arena)

‘All the Way’

Through May 8

1101 Sixth St., S.W.

$40-90

202-488-3300

When Cameron Folmar was cast as Alabama’s notoriously racist former governor George Wallace in “All the Way,” Robert Schenkkan’s Tony-winning play about President Lyndon Johnson’s struggle to pass the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964, some of his friends were a little put off. But those who understood the dramatic possibilities implicit in playing a dark character instantly realized what a juicy part the actor had landed.

Going into Arena Stage’s production, Folmar, who’s gay, didn’t know a lot about Wallace — what he most remembered about was the well-known photo of then-Gov. Wallace standing in a doorway blocking black students from enrolling at the University of Alabama. With his vow of “segregation forever,” Wallace seems cartoonishly villainous, Folmar says.

“But like a lot of seemingly one-dimensional character, he’s actually complex. Though I must confess with a character like him it was challenging to find something in myself to bring him out in a realistic way.”

“All the Way” was commissioned by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival and premiered in 2012 during an election season. If it was timely then and moreso now.

“Not a week goes by that comparisons are not made between Donald Trump and Wallace,” says Folmar, a Georgia native who calls New York City home. “Because of Trump and Cruz too, civil rights are center. The Civil Rights Act talked about in the play outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Like Trump, Wallace did a lot of chest thumping and played to the fear and anger of people who felt left out and left behind.”

From the start, Folmar was excited to be part of this production and eager to work at Arena for the first time.

“When the cast gathered for a read through of the play, we all felt turbo charged with a rush of excitement. What had been abstract had suddenly become real. We’re in D.C. where some of the characters are still alive, barely so in some cases. But there are plenty of people around who knew these people.”

Staged by Kyle Donnelly, the play features 66 named characters played by 17 actors. With the exception of President Johnson (played by Jack Willis, who created the role in Oregon), the play’s many historical figures deliver a message, hit home some points and disappear back into the wings.

“Because Jack is so good and so familiar with the part,” Folmar says, “I think we were able to focus on the other many characters in a way that would have been impossible. He’s the sun and we’re all orbiting around that giant figure.”

As Wallace, Folmar pops on stage for four rabble-rousing speeches. He also plays other parts including California Congressman James C. Corman, a liberal Democrat who championed the Civil Rights Act, and Walter Reuther, former president of the United Automobile Workers at a time when unions had significant power.

“It’s episodic with many short scenes, but that’s really the best way to tell this story,” Folmer says. “Prior to serving as vice president and then president after Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson was in both houses of Congress. He’s known as a master manipulator who got thousands of bills through in a way we can’t imagine today. In the play he’s portrayed as having a 15-track mind and is constantly juggling with both hands and feet. Characters are coming at him from all directions.”

Folmar’s relationship with the D.C. theater scene began in New York. He studied with Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Michael Kahn when Kahn was also head of the acting program at Juilliard in Manhattan. Months after Folmar graduated in 1999 Kahn cast him as Edgar in “King Lear.”

“It was a big break for me,” says Folmer, 45. “And since then I’ve been lucky with parts especially in D.C.”

Washington highlights include “Five by Tenn,” a collection of rarely produced Tennessee Williams one-acts including“And Tell Sad Stories of the Deaths of Queens” in which Folmar played an aging, lonely drag queen; Alan Bennett’s “The Habit of Art” at Studio Theatre; and Oscar Wilde’s “An Ideal Husband” at Shakespeare. On and off-Broadway he enjoyed a long run in the hit comedy “The 39 Steps.”

“I’m happiest on stage when I’m covered in dirt and look like hell and am insane. Or when I’m dressed fabulously, well spoken and wealthy and carrying a glass of Champagne. Either extreme is what it’s all about for me.”

Folmar is comfortably out in his career. He came out at 18 while doing summer theater in New Jersey.

“I fell hard in love with a fellow actor. And that was it. I remember thinking ‘I’m gay. Nobody’s going to tell me it’s wrong and I’m not interested in trying to hide it.’ Prior to that, I’d had secret boyfriends in high school. We’d park in cornfields and fool around like all the other kids in Georgia. While there have been good closeted actors, I think it’s better to be out,” he says. “It’s important to listen with your heart. Really what you have in the end is your own experience and if you’re looking at that through gauze, it’s impossible to reach it as deeply.”

Theater

Out actor Kevin Cahoon on starring role in ‘Chez Joey’

Arena production adapted from Broadway classic ‘Pal Joey’

‘Chez Joey’

Through March 15

Arena Stage

1101 Sixth St., S.W.

Tickets start at $93

Arenastage.org

As Melvin Snyder in the new musical “Chez Joey,” out actor Kevin Cahoon plays a showbiz society columnist who goes by the name Mrs. Knickerbocker. He functions as a sort of liaison between café society and Chicago’s Black jazz scene circa 1940s. It’s a fun part replete with varied insights, music, and dance.

“Chez Joey” is adapted from the Broadway classic “Pal Joey” by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart. It’s inspired by John O’Hara’s stories based on the exploits of a small-time nightclub singer published in The New Yorker.

A warm and humorous man, Cahoon loves his work. At just six, he began his career as a rodeo clown in Houston. He won the Star Search teen division at 13 singing songs like “Some People” from “Gypsy.” He studied theater at New York University and soon after graduating set to work playing sidekicks and comedic roles.

Over the years, Cahoon has played numerous queer parts in stage productions including “Hedwig and the Angry Inch,” “La Cage aux Folles,” “Rocky Horror” as well as Peanut in “Shucked,” and George the keyboardist in “The Wedding Singer,” “a sort of unicorn of its time,” says Cahoon.

Co-directed by Tony Goldwyn and the great Savion Glover, “Chez Joey” is a terrific and fun show filled with loads of talent. Its relevant new book is by Richard Lagravenese.

On a recent Monday off from work, Cahoon shared some thoughts on past and current happenings.

WASHINGTON BLADE: Is there a through line from Kevin, the six-year-old rodeo clown, to who we see now at Arena Stage?

KEVIN CAHOON: Anytime I want to land a joke in a theater piece it goes back to that rodeo clown. It doesn’t matter if it’s Arena’s intimate Kreeger Theatre or the big rodeo at the huge Houston Astrodome.

I was in the middle stadium and there was an announcer — a scene partner really. And we were doing a back and forth in hopes of getting laughs. At that young age I was trying to understand what it takes to get laughs. It’s all about timing. Every line.

BLADE: Originally, your part in “Chez Joey” Melvin was Melba who sings “Zip,” a clever woman reporter’s song. It was sort of a star feature, where they could just pop in a star in the run of “Pal Joey.”

CAHOON: That’s right. And in former versions it was played by Martha Plimpton and before her Elaine Stritch. For “Chez Joey,” we switched gender and storyline.

We attempted to do “Zip” up until two days before we had an audience at Arena. Unexpectedly they cut “Zip” and replaced it with a fun number called “I Like to Recognize the Tune,” a song more connected to the story.

BLADE: Wow. You must be a quick study.

CAHOON: Well, we’re working with a great band.

BLADE: You’ve played a lot of queer parts. Any thoughts on queer representation?

CAHOON: Oh yes, definitely. And I’ve been very lucky that I’ve had the chance to portray these characters and introduce them to the rest of the world. I feel honored.

After originating Edna, the hyena on Broadway in “The Lion King,” I left that to do “Hedwig and the Angry Inch” as standby for John Cameron Mitchell, doing one show a week for him.

Everyone thought I was crazy to leave the biggest musical of our time with a personal contract and getting paid more money that I’d ever made to get $400 a week at the downtown Jane Street Theatre in a dicey neighborhood.

At the time, I really felt like I was with cool kids. I guess I was. And I never regretted it.

BLADE: When you play new parts, do you create new backstories for the role?

CAHOON: Every single time! For Melvin, I suggested a line about chorus boys on Lakeshore Drive.

BLADE: What’s up next for Kevin Cahoon?

CAHOON: I’m about to do the New York Theatre Workshop Gala; I’ve been doing it for nine years in a row. It’s a huge job. I’ll also be producing the “Cats: The Jellicle Ball” opening on Broadway this spring; it’s a queer-centric uptown vogue ball with gay actor André de Shields reprising his role as “Old Deuteronomy.”

BLADE: There’s a huge amount of talent onstage in “Chez Joey.”

CAHOON: There is. I’m sharing a dressing room with Myles Frost who plays Joey. He won accolades for playing Michael Jackson on Broadway. We’ve become great friends. He’s a miracle to watch on stage. And Awa [Sal Secka], a D.C. local, is great. Every night the audience falls head over heels for her. When this show goes to New York, Awa will, no doubt, be a giant star.

BLADE: Do you think “Chez Joey” might be Broadway bound?

CAHOON: I have a good feeling it is. I’ve done shows out of town that have high hopes and pedigree, but don’t necessarily make it. “Chez Joey” is a small production, it’s funny, and audiences seem to love it.

Theater

José Zayas brings ‘The House of Bernarda Alba’ to GALA Hispanic Theatre

Gay Spanish playwright Federico García Lorca wrote masterpiece before 1936 execution

‘The House of Bernarda Alba’

Through March 1

GALA Hispanic Theatre

3333 14th St., N.W.

$27-$52

Galatheatre.org

In Federico García Lorca’s “The House of Bernarda Alba,” now at GALA Hispanic Theatre in Columbia Heights, an impossibly oppressive domestic situation serves, in short, as an allegory for the repressive, patriarchal, and fascist atmosphere of 1930s Spain

The gay playwright completed his final and arguably best work in 1936, just months before he was executed by a right-wing firing squad. “Bernarda Alba” is set in the same year, sometime during a hot summer in rural Andalusia, the heart of “España profunda” (the deep Spain), where traditions are deeply rooted and mores seldom challenged.

At Bernarda’s house, the atmosphere, already stifling, is about to get worse.

On the day of her second husband’s funeral, Bernarda Alba (superbly played by Luz Nicolás), a sixtyish woman accustomed to calling the shots, gathers her five unmarried daughters (ages ranging from 20 to 39) and matter-of-factly explain what’s to happen next.

She says, “Through the eight years of mourning not a breeze shall enter this house. Consider the doors and windows as sealed with bricks. That’s how it was in my father’s house and my grandfather’s. Meanwhile, you can embroider your trousseaux.”

It’s not an altogether sunny plan. While Angustias (María del Mar Rodríguez), Bernarda’s daughter from her first marriage and heiress to a fortune, is betrothed to a much younger catch, Pepe el Romano, who never appears on stage, the remaining four stand little chance of finding suitable matches. Not only are they dowry-less, but no men, eligible or otherwise, are admitted into their mother’s house.

Lorca is a literary hero known for his mastery of both lyrical poetry and visceral drama; still, “Bernarda Alba’s” plotline might suit a telenovela. Despotic mother heads a house of adult daughters. Said daughters are churning with passions and jealousies. When sneaky Martirio (Giselle Gonzáles) steals the photo of Angustias’s fiancé all heck kicks off. Lots of infighting and high drama ensue. There’s even a batty grandmother (Alicia Kaplan) in the wings for bleak comic relief.

At GALA, the modern classic is lovingly staged by José Zayas. The New York-based out director has assembled a committed cast and creative team who’ve manifested an extraordinarily timely 90-minute production performed in Spanish with English subtitles easily ready seen on multiple screens.

In Lorca’s stage directions, he describes the set as an inner room in Bernarda’s house; it’s bright white with thick walls. At GALA, scenic designer Grisele Gonzáles continues the one-color theme with bright red walls and floor and closed doors. There are no props.

In the airless room, women sit on straight back chairs sewing. They think of men, still. Two are fixated on their oldest siter’s hunky betrothed. Only Magdelena (Anna Malavé), the one sister who truly mourns their dead father, has given up on marriage entirely.

The severity of the place is alleviated by men’s distant voices, Koki Lortkipanidze’s original music, movement (stir crazy sisters scratching walls), and even a precisely executed beatdown choreographed by Lorraine Ressegger-Slone.

In a short yet telling scene, Bernarda’s youngest daughter Adela (María Coral) proves she will serve as the rebellion to Bernarda’s dictatorship. Reluctant to mourn, Adela admires her reflection. She has traded her black togs for a seafoam green party dress. It’s a dreamily lit moment (compliments of lighting designer Hailey Laroe.)

But there’s no mistaking who’s in charge. Dressed in unflattering widow weeds, her face locked in a disapproving sneer, Bernarda rules with an iron fist; and despite ramrod posture, she uses a cane (though mostly as a weapon during one of her frequent rages.)

Bernarda’s countenance softens only when sharing a bit of gossip with Poncia, her longtime servant convincingly played by Evelyn Rosario Vega.

Nicolás has appeared in “Bernarda Alba” before, first as daughter Martirio in Madrid, and recently as the mother in an English language production at Carnegie Melon University in Pittsburgh. And now in D.C. where her Bernarda is dictatorial, prone to violence, and scarily pro-patriarchy.

Words and phrases echo throughout Lorca’s play, all likely to signal a tightening oppression: “mourning,” “my house,” “honor,” and finally “silence.”

As a queer artist sympathetic to left wing causes, Lorca knew of what he wrote. He understood the provinces, the dangers of tyranny, and the dimming of democracy. Early in Spain’s Civil War, Lorca was dragged to the the woods and murdered by Franco’s thugs. Presumably buried in a mass grave, his remains have never been found.

Theater

Magic is happening for Round House’s out stage manager

Carrie Edick talks long hours, intricacies of ‘Nothing Up My Sleeve’

‘Nothing Up My Sleeve’

Through March 15

Round House Theatre

4545 East-West Highway

Bethesda, Md. 20814

Tickets start at $50

Roundhousetheatre.org

Magic is happening for out stage manager Carrie Edick.

Working on Round House Theatre’s production of “Nothing Up My Sleeve,” Edick quickly learned the ways of magicians, their tricks, and all about the code of honor among those who are privy to their secrets.

The trick-filled, one-man show starring master illusionist Dendy and staged by celebrated director Aaron Posner, is part exciting magic act and part deeply personal journey. The new work promises “captivating storytelling, audience interaction, jaw-dropping tricks, and mind-bending surprises.”

Early in rehearsals, there was talk of signing a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) for production assistants. It didn’t happen, and it wasn’t necessary, explains Edick, 26. “By not having an NDA, Dendy shows a lot of trust in us, and that makes me want to keep the secrets even more.

“Magic is Dendy’s livelihood. He’s sharing a lot and trusting a lot; in return we do the best we can to support him and a large part of that includes keeping his secrets.”

As a production assistant (think assistant stage manager), Edick strives to make things move as smoothly as possible. While she acknowledges perfection is impossible and theater is about storytelling, her pursuit of exactness involves countless checklists and triple checks, again and again. Six day weeks and long hours are common. Stage managers are the first to arrive and last to leave.

This season has been a lot about learning, adds Edick. With “The Inheritance” at Round House (a 22-week long contract), she learned how to do a show in rep which meant changing from Part One to Part Two very quickly; “In Clay” at Signature Theatre introduced her to pottery; and now with “Nothing Up My Sleeve,” she’s undergoing a crash course in magic.

She compares her career to a never-ending education: “Stage managers possess a broad skillset and that makes us that much more malleable and ready to attack the next project. With some productions it hurts my heart a little bit to let it go, but usually I’m ready for something new.”

For Edick, theater is community. (Growing up in Maryland, she was a shy kid whose parents signed her up for theater classes.) Now that community is the DMV theater scene and she considers Round House her artistic home. It’s where she works in different capacities, and it’s the venue in which she and actor/playwright Olivia Luzquinos chose to be married in 2024.

Edick came out in middle school around the time of her bat mitzvah. It’s also around the same time she began stage managing. Throughout high school she was the resident stage manager for student productions, and also successfully participated in county and statewide stage management competitions which led to a scholarship at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) where she focused on technical theater studies.

Edick has always been clear about what she wants. At an early age she mapped out a theater trajectory. Her first professional gig was “Tuesdays with Morrie” at Theatre J in 2021. She’s worked consistently ever since.

Stage managing pays the bills but her resume also includes directing and intimacy choreography (a creative and technical process for creating physical and emotional intimacy on stage). She names Pulitzer Prize winning lesbian playwright Paula Vogel among her favorite artists, and places intimacy choreographing Vogel’s “How I learned to Drive” high on the artistic bucket list.

“To me that play is heightened art that has to do with a lot of triggering content that can be made very beautiful while being built to make you feel uncomfortable; it’s what I love about theater.”

For now, “Nothing Up My Sleeve” keeps Edick more than busy: “For one magic trick, we have to set up 100 needles.”

Ultimately, she says “For stage managers, the show should stay the same each night. What changes are audiences and the energy they bring.”

-

Virginia5 days ago

Virginia5 days agoArlington LGBTQ bar Freddie’s celebrates 25th anniversary

-

National4 days ago

National4 days agoSupreme Court deals blow to trans student privacy protections

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoD.C. Black Pride theme, performers announced at ‘Speakeasy’

-

Opinions3 days ago

Opinions3 days agoWhy innovation matters for Black health