Books

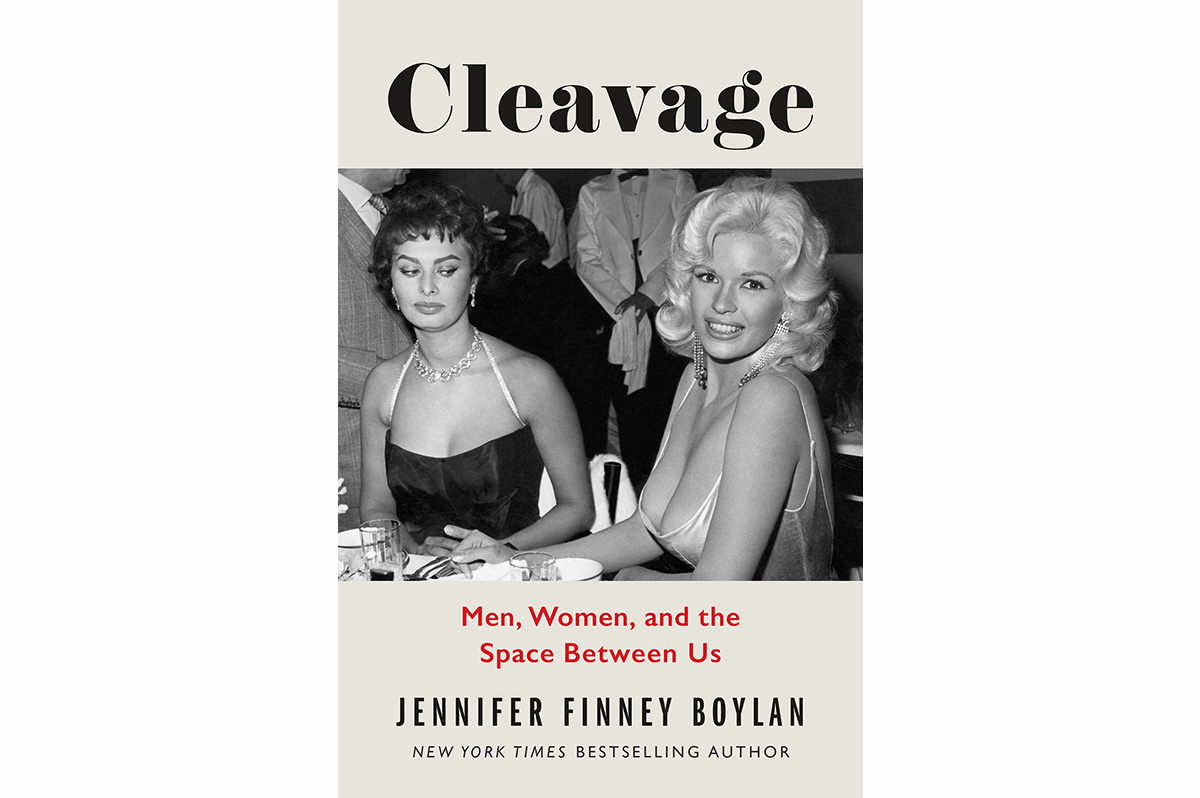

Jennifer Finney Boylan busts through hate with ‘Cleavage’

Bestselling author, scholar promoted latest book in D.C. in February

When bestselling author Jennifer Finney Boylan came to D.C. earlier this month to promote her new memoir, “Cleavage,” she chose an on-stage partner with whom she has some history, to pose questions before a gaggle of book lovers, members of the LGBTQ community and fans. Transgender Delaware Congresswoman Sarah McBride provided a bookend of sorts, given that Boylan fulfilled that same role when McBride published her first memoir, “Tomorrow Will Be Different.”

“Jenny moderated the first discussion when my book came out in 2018 at the Strand in New York City,” McBride said. “And I was star-struck. I was intimidated, because you were, really, for me, the first contemporary example of a trans person that wasn’t, as you write about in this book, on ‘Jerry Springer.’ Being exploited.”

“And that’s the hardest thing, I think, that some of us experience when we were growing up,” said Boylan. “At least for me, it was, I almost never saw anybody like me on TV or in the movies. And if there was anyone even vaguely like me, they were usually either a villain or someone who was a figure of ridicule. Thank goodness all that has changed!” The crowd laughed along, knowingly.

But it was not just McBride who joined Boylan in the Politics and Prose bookstore at the Wharf. They were joined by other trans trailblazers: Activist Mara Keisling, Adm. (ret.) Rachel Levine, former Department of Defense official Amanda Simpson and journalist and activist Charlotte Clymer.

This event was just one stop on a whirlwind national tour to promote Boylan’s book, featuring Roxane Gay in New York, WBUR senior arts and culture reporter Cristela Guerra in Cambridge, and other stops with celebrity guests from Maine to Santa Cruz, Calif.

Boylan has explained at each stop what compelled her to write a sequel to her bestselling first memoir, “She’s Not There: A Life in Two Genders,” from 2003.

“If you’re a writer, stories are my bread and butter,” she said. “And there are a lot of stories I haven’t told. There are also some stories I wanted to revisit.”

“Cleavage,” she revealed, was to acknowledge that things have changed since she told the world she was trans.

“One of the stories I wanted to look at was the difference between coming out now and coming out 25 years ago,” said Boylan. “I have a transgender daughter. She came out six or seven years ago. And how did I react? I freaked out. Did I put my arms around my child and say, ‘Love will prevail?’ No. I remember literally jolting in my chair. Literally. It was as if I had been struck by lightning. And my first thought was, ‘Damn.’ Because, as most of us know, it’s a hard life. And even when things go about as well as they can, which I think—and there are a lot of success stories in this room—it’s still a hard life.”

After conversations with the author at these events, the hosts have opened the floor to questions from the audience, often not just about Boylan’s memoir but about the state of affairs in Washington and across the nation.

At the event at the New York Public Library earlier this month, Gay fielded this question from someone who moderates a trans nonbinary peer support group: “What can you tell our members to give them hope?” Boylan took a moment to consider the question.

“Here’s what we know. Right now, things are really bad. And they’re not just bad for queer and nonbinary and trans people. They’re bad for a lot of people. They’re bad for anybody who doesn’t kind of fit into this 1950s all-male review of singing and dancing that these people have prepared for us. It is hard,” she said.

“We have been through hard times before in this country. We have been through a civil war. We’ve been through depression. We’ve been through, well, you know, the shit keeps hitting the fan. But this moment, as aggressive as it feels, will not last forever. And this will not define us. And I think that, what’s that Paul Simon song? ‘I believe in the future we will suffer no more. Maybe not in my lifetime, but in yours, I feel sure.’” Boylan was referencing the 1990 song, ‘The Cool, Cool River’ by Paul Simon. “Oh, gee, do I have to be dead for things to get better? I hope not,” added Boylan, before continuing her message.

“This moment, which feels so oppressive, is not the last word,” she said. “This is just beginning. And we have not, unfortunately, we have not yet started to fight back. But we are going to fight back. And, you know, I hope I can say they don’t know what’s coming for them! So, let’s make that clear. Is this really what the majority of Americans wanted? This? I don’t believe it. I won’t believe it. And so, we just have to work for it and not lose our hope. And, yeah, keep telling your stories.”

Simpson told her story at the event in D.C., comparing how the movement for marriage equality differs from the movement for trans rights.

“It was about the neighbors you know, and that there were LGBT people in your neighborhood,” she said. “I was an aerospace engineer. We had firemen and policemen. We had military people, all doing these ads saying, ‘Look, we’re just your neighbors. Get to know the individual, not this larger concept of an LGBT person,’ and that worked. And I think we have to do that again. It’s about that personal introduction to them. We do these things to show that we’re just like everyone else. We’re human. But we have a leader sitting down the street who has made this such a sharp point to help energize or misdirect what’s going on. And being a Jewish woman, I remember—well, not personally, but I look back at what happened in 1933 and 35 overseas and think about the similarities of picking on one group of defenseless, underrepresented people to help focus everyone else to be behind you. And that’s, I think, what we’re seeing.”

Levine, a former assistant secretary of Health and Human Services in the Biden-Harris administration, followed-up.

“I would agree with Amanda about the political aspect of this, it’s been very well reported that this is a specific strategy, an iterative strategy developed by right-wing think tanks in Washington to split the progressive movement,” Levine said. “They lost marriage, did not feel that they could gain that back, and so they were looking for a scapegoat, and thought that they could make progress by demonizing us and otherizing us, starting with trans athletes, then going on to transgender medicine or gender-affirming care for youth, and now you see, you know, denying that we exist at all, and then potentially trying to go back to sexual orientation as well … It was a specific political and ideological strategy which, unfortunately, they weaponized and were very successful in doing that, and I think that we were conveniently there, but now, what do we do? Now here we are, in this extremely challenging environment, and the key will be how our community, supported by the broader LGBTQ community and our allies, respond.”

Keisling pointed part of the blame for right-wing attacks on the community itself, for its handling of trans athletes and its hyperfocus on JK Rowling, who she called “a jerk.”

“They landed on this sports thing, which we totally screwed up,” said Keisling. “Instead of talking about the seven-year-old who wants to play soccer with her friends, we were talking about Olympians and NCAA swimmers, which we should have been defending against, but that wasn’t our strongest argument. What I have been saying for 10 years is we don’t seem to understand, we as progressives, that we are also part of the problem. We are not focused on what narrowness we’re hearing. Now, I believe this is about populism and politics, as Amanda said. But they came over and started picking people off on our side, and we have never done that. Progressives won’t do that. Progressives will never, ever, ever welcome somebody to come over from the other side. And that’s a mistake, and we’ve got to figure out how to do that, how to reach out to people, how to win over people. And once we win them over, we have to fucking embrace them. And most of the activists I know won’t do that.”

McBride stepped in to concur.

“I agree with you, Mara,” she said, “I think we have lost the art of coalition building. We have created a space where there is no room for imperfect allies. We have eliminated space for people to grow because they at least perceive that they will be seen as permanently guilty for having been wrong.”

Clymer agreed.

“Say what you will about the Evangelical Church, and I have a lot of things to say about the Evangelical Church, but their greatest strength is that there is a very low threshold for entry,” she said. “You show up to the congregations, you don’t have to know anything, you don’t have to have any knowledge of theory or practice or whatever, you just show up and you’re welcome to the pulpit. We as a progressive movement, and I think to your point, Mara, we do not do a very good job of keeping a welcome threshold for entry into the movement. We tell folks that if you don’t know this sort of thing, or this theory, or if you’re not aware of this or that or whatever, we make people afraid to err, make mistakes. And I do think we need to get better at that.”

Boylan got the last word.

“I think that we were defined with some of the hardest issues to understand. And rather than the fact that, you know, I don’t particularly want to play sports with your kid. I want to teach them English,” she said, then turned to McBride. “You are not here to play sports. You are here to represent the people of Delaware. So, the main thing we want is we want to be able to do our jobs. We want to be able to walk tall. And guess what? We also would like to be left alone.”

Boylan was asked if there was a bumper sticker for trans rights that could match what “Love is Love” accomplished for marriage equality. Her response: “Love is the wise person’s revenge. Love is the best revenge in the world.”

Books

Embracing the chaos can be part of the fun

‘Make Sure You Die Screaming’ offers many twists and turns

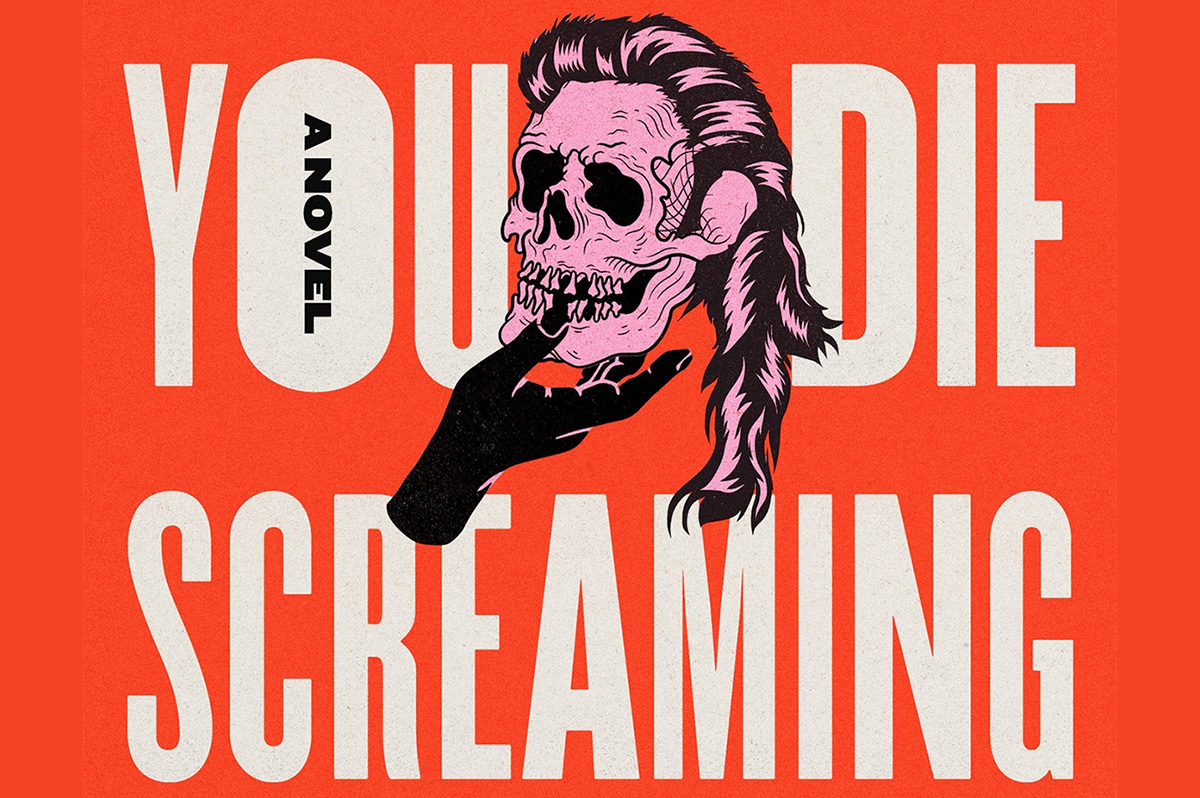

‘Make Sure You Die Screaming’

By Zee Carlstrom

c.2025, Random House

$28/304 pages

Sometimes, you just want to shut the door and forget what’s on the other side.

You could just wipe it from your memory, like it didn’t occur. Or create an alternate universe where bad things never happen to you and where, as in the new novel “Make Sure You Die Screaming” by Zee Carlstrom, you can pretend not to care.

Their mother called them “Holden,” but they’d stopped using that name and they hadn’t decided what to use now. What do you call an alcoholic, queer, pessimistic former ad executive who’s also “The World’s First Honest White Man,” although they no longer identify as a man? It’s a conundrum that they’ll have to figure out soon because a cop’s been following them almost since they left Chicago with Yivi, their psychic new best friend.

Until yesterday, they’d been sleeping on a futon in some lady’s basement, drinking whatever Yivi mixed, and trying not to think about Jenny. They killed Jenny, they’re sure of it. And that’s one reason why it’s prudent to freak out about the cop.

The other reason is that the car they’re driving was stolen from their ex-boyfriend who probably doesn’t know it’s gone yet.

This road trip wasn’t exactly well-planned. Their mother called, saying they were needed in Arkansas to find their father, who’d gone missing so, against their better judgment, they packed as much alcohol as Yivi could find and headed south. Their dad had always been unique, a cruel man, abusive, intractable; he suffered from PTSD, and probably another half-dozen acronyms, the doctors were never sure. They didn’t want to find him, but their mother called…

It was probably for the best; Yivi claimed that a drug dealer was chasing her, and leaving Chicago seemed like a good thing.

They wanted a drink more than anything. Except maybe not more than they wanted to escape thoughts of their old life, of Jenny and her death. And the more miles that passed, the closer they came to the end of the road.

If you think there’s a real possibility that “Make Sure You Die Screaming” might run off the rails a time or three, you’re right. It’s really out there, but not always in a bad way. Reading it, in fact, is like squatting down in a wet, stinky alley just after the trash collector has come: it’s filthy, dank, and profanity-filled. Then again, it’s also absurd and dark and philosophical, highly enjoyable but also satisfying and a little disturbing; Palahniuk-like but less metaphoric.

That’s a stew that works and author Zee Carlstrom stirs it well, with characters who are sardonic and witty while fighting the feeling that they’re unredeemable losers – which they’re not, and that becomes obvious.

You’ll see that all the way to one of the weirdest endings ever.

Readers who can withstand this book’s utter confusion by remembering that chaos is half the point will enjoy taking the road trip inside “Make Sure You Die Screaming.”

Just buckle up tight. Then shut the door, and read.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Two new books on dining out LGBTQ-style

Visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers

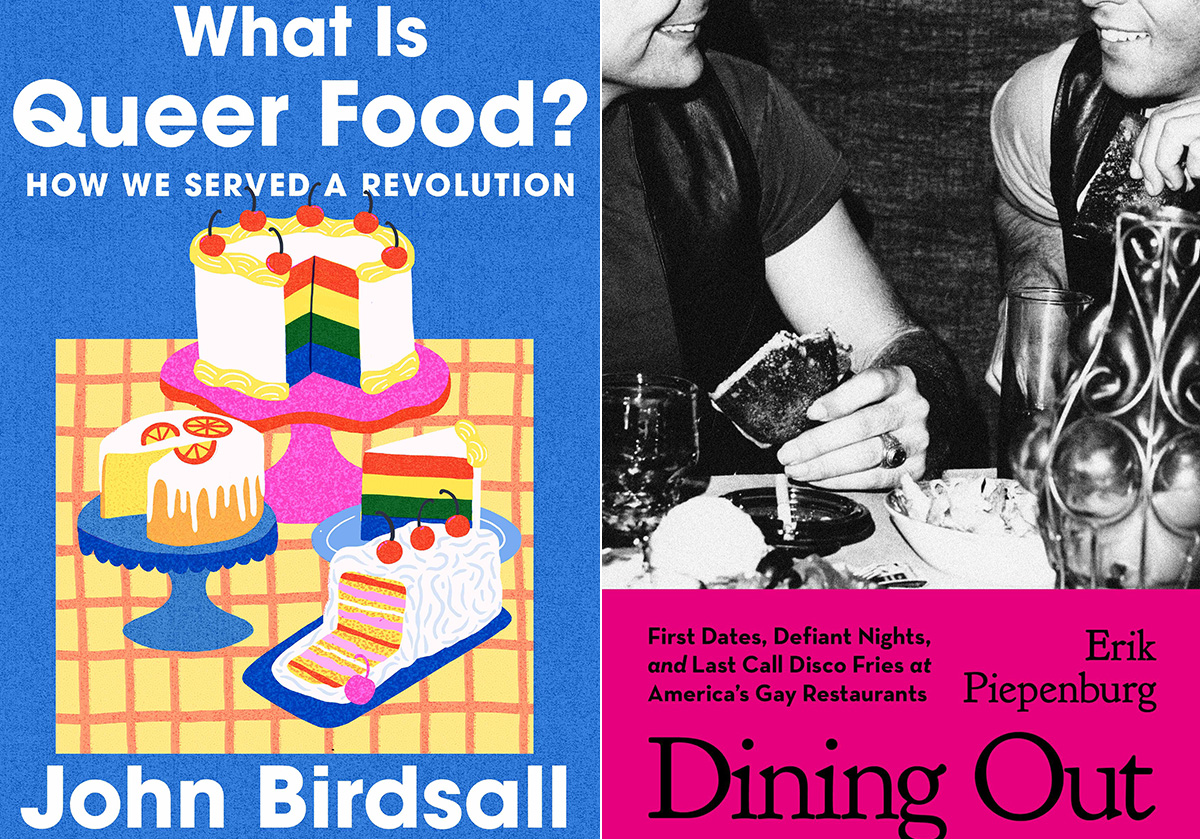

‘What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution’

By John Birdsall

c.2025, W.W. Norton

$29.99/304 pages

‘Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants’

By Erik Piepenburg

c.2025, Grand Central

$30/352 pages

You thought a long time about who sits where.

Compatibility is key for a good dinner party, so place cards were the first consideration; you have at least one left-hander on your guest list, and you figured his comfort into your seating chart. You want the conversation to flow, which is music to your ears. And you did a good job but, as you’ll see with these two great books on dining LGBTQ-style, it’s sometimes not who sits where, but whose recipes were used.

When you first pick up “What is Queer Food?” by John Birdsall, you might miss the subtitle: “How We Served a Revolution.” It’s that second part that’s important.

Starting with a basic gay and lesbian history of America, Birdsall shows how influential and (in)famous 20th century queer folk set aside the cruelty and discrimination they received, in order to live their lives. They couldn’t speak about those things, he says, but they “sat down together” and they ate.

That suggested “a queer common purpose,” says Birdsall. “This is how who we are, dahling, This is how we feed our own. This is how we stay alive.”

Readers who love to cook, bake or entertain, collect cookbooks, or use a fork will want this book. Its stories are nicely served, they’re addicting, and they may send you in search of cookbooks you didn’t know existed.

Sometimes, though, you don’t want to be stuck in the kitchen, you want someone else to bring the grub. “Dining Out” by Erik Piepenburg is an often-nostalgic, lively look at LGBTQ-friendly places to grab a meal – both now and in the past.

In his introduction, Piepenburg admits that he’s a journalist, “not a historian or an academic,” which colors this book, but not negatively. Indeed, his journeys to “gay restaurants” – even his generous and wide-ranging definitions of the term – happily influence how he presents his narrative about eateries and other establishments that have fed protesters, nourished budding romances, and offered audacious inclusion.

Here, there are modern tales of drag lunches and lesbian-friendly automats that offered “cheap food” nearly a century ago. You’ll visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers on holidays. Stepping back, you’ll read about AIDS activism at gay-friendly establishments, and mostly gay neighborhood watering holes. Go underground at a basement bar; keep tripping and meet proprietors, managers, customers and performers. Then take a peek into the future, as Piepenburg sees it.

The locales profiled in “Dining Out” may surprise you because of where they can be found; some of the hot-spots practically beg for a road trip.

After reading this book, you’ll feel welcome at any of them.

If these books don’t shed enough light on queer food, then head to your favorite bookstore or library and ask for help finding more. The booksellers and librarians there will put cookbooks and history books directly in your hands, and they’ll help you find more on the history and culture of the food you eat. Grab them and you’ll agree, they’re pretty tasty reads.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

You’re going to be on your feet a lot this month.

Marching in parades, dancing in the streets, standing up for people in your community. But you’re also likely to have some time to rest and reflect – and with these great new books, to read.

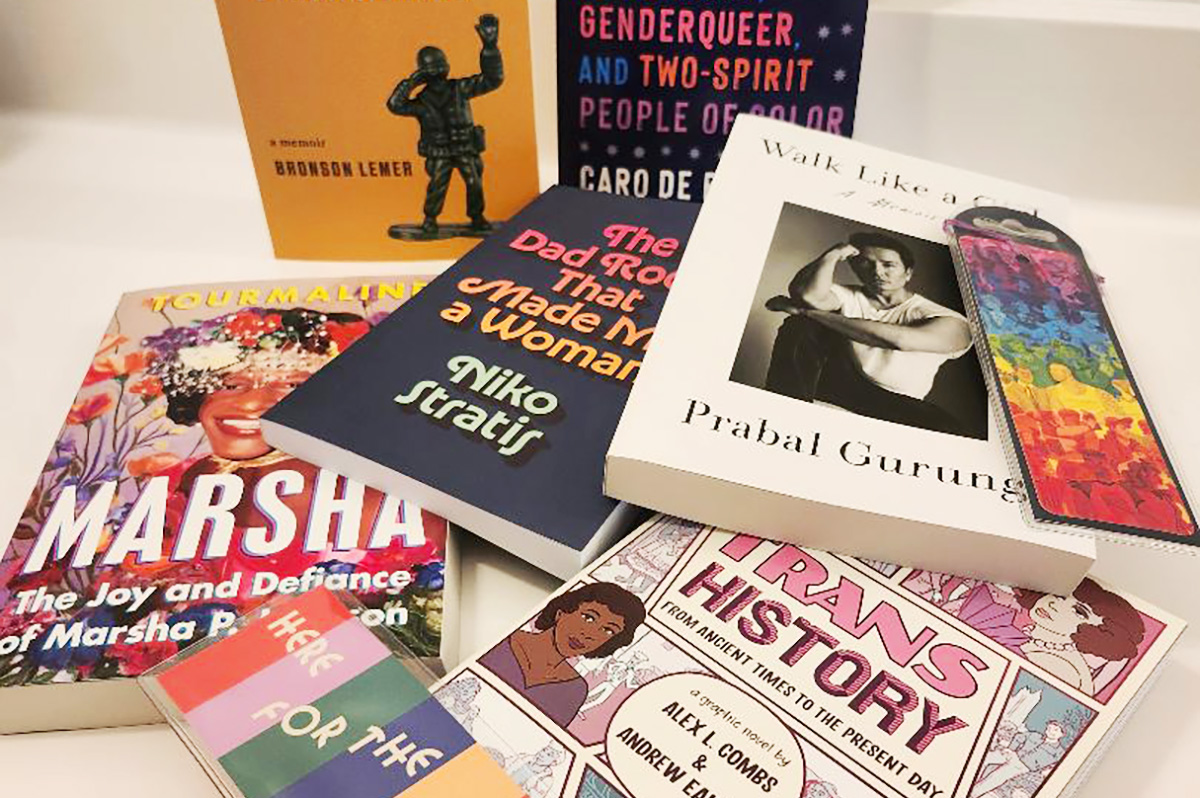

First, dip into a biography with “Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson” by Tourmaline (Tiny Rep Books, $30), a nice look at an icon who, rumor has it, threw the brick that started a revolution. It’s a lively tale about Marsha P. Johnson, her life, her activism before Stonewall and afterward. Reading this interesting and highly researched history is a great way to spend some time during Pride month.

For the reader who can’t live without music, try “The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman” by Niko Stratis (University of Texas Press, $27.95), the story of being trans, searching for your place in the world, and finding it in a certain comfortable genre of music. Also look for “The Lonely Veteran’s Guide to Companionship” by Bronson Lemer (University of Wisconsin Press, $19.95), a collection of essays that make up a memoir of this and that, of being queer, basic training, teaching overseas, influential books, and life.

If you still have room for one more memoir, try “Walk Like a Girl” by Prabal Gurung (Viking, $32.00). It’s the story of one queer boy’s childhood in India and Nepal, and the intolerance he experienced as a child, which caused him to dream of New York and the life he imagined there. As you can imagine, dreams and reality collided but nonetheless, Gurung stayed, persevered, and eventually became an award-winning fashion designer, highly sought by fashion icons and lovers of haute couture. This is an inspiring tale that you shouldn’t miss.

No Pride celebration is complete without a history book or two.

In “Trans History: From Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Alex L. Combs & Andrew Eakett ($24.99, Candlewick Press), you’ll see that being trans is something that’s as old as humanity. One nice part about this book: it’s in graphic novel form, so it’s lighter to read but still informative. Lastly, try “So Many Stars: An Oral History of Trans, Nonbinary, Genderqueer, and Two-Spirit People of Color” by Caro De Robertis (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. $32.00) a collection of thoughts, observations, and truths from over a dozen people who share their stories. As an “oral history,” you’ll be glad to know that each page is full of mini-segments you can dip into anywhere, read from cover to cover, double-back and read again. It’s that kind of book.

And if these six books aren’t enough, if they don’t quite fit what you crave now, be sure to ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for help. There are literally tens of thousands of books that are perfect for Pride month and beyond. They’ll be able to determine what you’re looking for, and they’ll put it directly in your hands. So stand up. March. And then sit and read.

-

U.S. Supreme Court4 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court4 days agoSupreme Court to consider bans on trans athletes in school sports

-

Out & About4 days ago

Out & About4 days agoCelebrate the Fourth of July the gay way!

-

Virginia4 days ago

Virginia4 days agoVa. court allows conversion therapy despite law banning it

-

Opinions5 days ago

Opinions5 days agoCan we still celebrate Fourth of July this year?