Theater

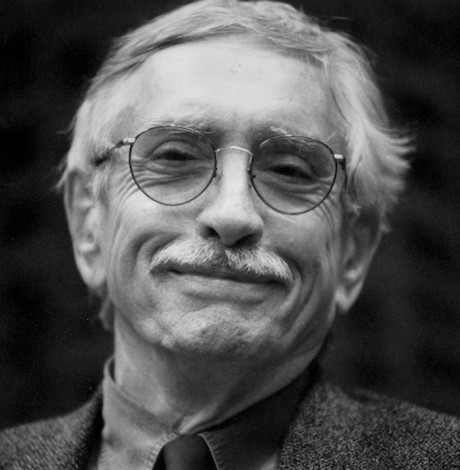

Remembering Edward Albee

Irascible playwright was towering figure in American theater

Edward Albee with Kathleen Turner, who played Martha in his play ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf’ on Broadway and at the Kennedy Center, in Washington in March, 2011. Albee said Turner brought a gravitas to the role he hadn’t sensed since the late Uta Hagen originated it on the stage. (Washington Blade file photo by Michael Key)

When playwright Edward Albee was honored by the annual Lambda Literary Awards in 2011, he told the audience, “A writer who happens to be gay or lesbian must be able to transcend self. I am not a gay writer. I am a writer who happens to be gay.” He added “Any definition that limits us is deplorable.”

Because the Lambda Awards celebrates writing from a queer perspective, his words weren’t exactly what his hosts and the gathered crowd wanted to hear. But that was Albee. He spoke his mind, sometimes ruffled feathers and wrote great plays.

On Sept. 16, Albee, the towering mainstay of American theater who gave us “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,” died after a short illness at home in Montauk, N.Y., the beach town on the tip of Long Island. He was 88.

Albee’s long career which garnered three Pulitzer Prizes and three Tony Awards (two for best play and one for lifetime achievement) began in earnest in 1958 when he was 30 with “The Zoo Story,” a one act about two very different and unacquainted men who uncomfortably meet on a park bench. Albee followed up this off-Broadway success with absurdist one-act plays “The Sandbox” and “The American Dream,” and a more traditional drama concerning racism “The Death of Bessie Smith.”

Next, he achieved big Broadway success with “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” in 1962. Five years later he scored big with his drawing room alienation drama “A Delicate Balance.” And in 1975, “Seascape,” an expressionist fantasy in which two couples (one human and the other, a pair of anthropomorphic lizards) meet on the beach to talk about love, relationships and the evolutionary process.

Throughout the following years he wrote many plays, allowed remounts of early works both with varying degrees of success before making a sort of a comeback in 1994 with “Three Tall Women,” an autobiographical work describing a mother who can’t handle her son being gay. In 2002 he enjoyed great success winning the Tony for “The Goat, or, Who is Sylvia,” (2002) the story of a successful Manhattan architect who has an affair with a farm animal.

Though not a Pulitzer winner, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” is considered the playwright’s masterpiece. Set in a small college town, the action unfolds over one late night of booze-fueled misbehavior and psychic combat. Awash in booze, middle-aged hosts George, a swampy professor, and his louche wife Martha welcome the college’s new fit young professor and his mousy wife Honey with drinks and an array of unnerving party games that keep the older couple both at odds and glued together and the younger pair on edge. Still, the play’s brilliant dialogue with its nonstop onslaught of unmatchable searing repartee and heartfelt words has proved a favorite of gay audiences of a certain age.

“Virginia Woolf” was adapted to the screen in a successful 1967 film starring then-real life raucous couple Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor as George and Martha, and the younger couple was played by George Siegel and Sandy Dennis. Taylor and Dennis both won Academy Awards for their efforts.

Some critics averred that Albee was in fact portraying two gay couples in “Virginia Woolf.” Substituting straight for gay relationships was a claim sometimes thrown at gay writers. Albee patently rejected the idea, and while he may have benefitted by retreating to the closet, he was out his entire career. Albee counted famed playwright Terrance McNally among his early lovers and sculptor Jonathan Thomas was his partner from 1971 until Thomas’ death in 2005 at 57.

Born in Washington, D.C. in 1928 to an unmarried woman, Albee was quickly adopted by wealthy New York couple Reed Albee, a vaudeville theater chain heir, and socialite Frances Cotter Albee. Rebellious from early on, Albee was expelled from a prep school and a military academy before graduating from the prestigious Choate School. His formal education ended when he was expelled from Trinity College in Connecticut. After leaving college, he lived in Greenwich Village where he wrote, did odd jobs and got by on trust fund payouts. More than once Albee told reporters that his parents didn’t know how to parent and he didn’t know how to be son.

Ford’s Theatre Artistic Director Paul Tetreault is saddened by the loss of his friend. Prior to taking the helm at Ford’s, Tetreault produced six or seven Albee plays at Houston’s Alley Theatre where Albee was often present and sometimes directed the productions. He describes Albee, who was known in theater circles as short tempered and difficult, as a bit misunderstood.

“Underneath the gruff exterior, he was a teddy bear,” Tetreault says. “And he believed in helping young theater artists and fine artists and would do almost anything for them. His commitment and dedication to young people was extraordinary. Eight years ago when Albee was 80, I heard him speak at Dickinson College. He spoke for an hour without notes, and took questions from the students for 45 minutes, standing the entire time. It was remarkable.”

Ever since arriving at Ford’s in 2004 with the intention of producing American classics, Tetreault wanted to do an Albee play. And now he’s realizing the goal with a winter production of “Virginia Woolf” staged by Aaron Posner and featuring a local cast including out actor Holly Twyford as Martha.

“We scheduled this long before we knew he wasn’t going to make it,” Tetreault says. “The play is one of the greatest ever written. It has comedy, drama, tragedy and pathos. As Martha, Holly will stretch every muscle she has as an actress. I think she’s going to be a complete revelation. I’m sorry Edward is going to miss it.”

Over the years, numerous Albee plays have been produced in the Washington area by both big and little theaters. D.C. likes Albee, and Tetreault explains why: “Albee has a layer and depth and intelligence that I think this city wants to embrace or believes they’re smart enough to watch. When people used to ask Albee what ‘Virginia Woolf’ was all about, he’d reply, ‘It’s about three-and-a-half hours long.’ He didn’t want to be whittled down to a sound bite. His work is complicated and nuanced and layered. He was a real genius and will be missed.”

Indeed.

Theater

Magic is happening for Round House’s out stage manager

Carrie Edick talks long hours, intricacies of ‘Nothing Up My Sleeve’

‘Nothing Up My Sleeve’

Through March 15

Round House Theatre

4545 East-West Highway

Bethesda, Md. 20814

Tickets start at $50

Roundhousetheatre.org

Magic is happening for out stage manager Carrie Edick.

Working on Round House Theatre’s production of “Nothing Up My Sleeve,” Edick quickly learned the ways of magicians, their tricks, and all about the code of honor among those who are privy to their secrets.

The trick-filled, one-man show starring master illusionist Dendy and staged by celebrated director Aaron Posner, is part exciting magic act and part deeply personal journey. The new work promises “captivating storytelling, audience interaction, jaw-dropping tricks, and mind-bending surprises.”

Early in rehearsals, there was talk of signing a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) for production assistants. It didn’t happen, and it wasn’t necessary, explains Edick, 26. “By not having an NDA, Dendy shows a lot of trust in us, and that makes me want to keep the secrets even more.

“Magic is Dendy’s livelihood. He’s sharing a lot and trusting a lot; in return we do the best we can to support him and a large part of that includes keeping his secrets.”

As a production assistant (think assistant stage manager), Edick strives to make things move as smoothly as possible. While she acknowledges perfection is impossible and theater is about storytelling, her pursuit of exactness involves countless checklists and triple checks, again and again. Six day weeks and long hours are common. Stage managers are the first to arrive and last to leave.

This season has been a lot about learning, adds Edick. With “The Inheritance” at Round House (a 22-week long contract), she learned how to do a show in rep which meant changing from Part One to Part Two very quickly; “In Clay” at Signature Theatre introduced her to pottery; and now with “Nothing Up My Sleeve,” she’s undergoing a crash course in magic.

She compares her career to a never-ending education: “Stage managers possess a broad skillset and that makes us that much more malleable and ready to attack the next project. With some productions it hurts my heart a little bit to let it go, but usually I’m ready for something new.”

For Edick, theater is community. (Growing up in Maryland, she was a shy kid whose parents signed her up for theater classes.) Now that community is the DMV theater scene and she considers Round House her artistic home. It’s where she works in different capacities, and it’s the venue in which she and actor/playwright Olivia Luzquinos chose to be married in 2024.

Edick came out in middle school around the time of her bat mitzvah. It’s also around the same time she began stage managing. Throughout high school she was the resident stage manager for student productions, and also successfully participated in county and statewide stage management competitions which led to a scholarship at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) where she focused on technical theater studies.

Edick has always been clear about what she wants. At an early age she mapped out a theater trajectory. Her first professional gig was “Tuesdays with Morrie” at Theatre J in 2021. She’s worked consistently ever since.

Stage managing pays the bills but her resume also includes directing and intimacy choreography (a creative and technical process for creating physical and emotional intimacy on stage). She names Pulitzer Prize winning lesbian playwright Paula Vogel among her favorite artists, and places intimacy choreographing Vogel’s “How I learned to Drive” high on the artistic bucket list.

“To me that play is heightened art that has to do with a lot of triggering content that can be made very beautiful while being built to make you feel uncomfortable; it’s what I love about theater.”

For now, “Nothing Up My Sleeve” keeps Edick more than busy: “For one magic trick, we have to set up 100 needles.”

Ultimately, she says “For stage managers, the show should stay the same each night. What changes are audiences and the energy they bring.”

Theater

‘Octet’ explores the depths of digital addiction

Habits not easily shaken in Studio Theatre chamber musical

‘Octet’

Through Feb. 26

Studio Theatre

1501 14th Street, N.W.

Tickets start at $55

Studiotheatre.org

David Malloy’s “Octet” delves deep into the depths of digital addiction.

Featuring a person ensemble, this extraordinary a capella chamber musical explores the lives of recovering internet addicts whose lives have been devastated by digital dependency; sharing what’s happened and how things have changed.

Dressed in casual street clothes, the “Friends of Saul” trickle into a church all-purpose room, check their cell phones in a basket, put away the bingo tables, and arrange folding chairs into a circle. Some may stop by a side table offering cookies, tea, and coffee before taking a seat.

The show opens with “The Forest,” a haunting hymn harking back to the good old days of an analog existence before glowing screens, incessant pings and texts.

“The forest was beautiful/ My head was clean and clear/Alone without fear/ The forest was safe/ I danced like a beautiful fool / One time some time.”

Mimicking an actual step meeting, there’s a preamble. And then the honest sharing begins, complete with accounts of sober time and slips.

Eager to share, Jessica (Chelsea Williams) painfully recalls being cancelled after the video of her public meltdown went viral. Henry (Angelo Harrington II) is a gay gamer with a Candy Crush problem. Toby (Adrian Joyce) a nihilist who needs to stay off the internet sings “So anyway/ I’m doing good/ Mostly/ Limiting my time/ Mostly.”

The group’s unseen founder Saul is absent, per usual.

In his stead Paula, a welcoming woman played with quiet compassion by Tracy Lynn Olivera, leads. She and her husband no longer connect. They bring screens to bed. In a love-lost ballad, she explains: “We don’t sleep well/ My husband I/ Our circadian rhythms corrupted/ By the sallow blue glow of a screen/ Sucking souls and melatonin/ All of my dreams have been stolen.”

After too much time spent arguing with strangers on the internet, Marvin, a brainy young father played by David Toshiro Crane, encounters the voice of a God.

Ed (Jimmy Kieffer) deals with a porn addiction. Karly (Ana Marcu) avoids dating apps, a compulsion compared to her mother’s addiction to slot machines.

Malloy, who not only wrote the music but also the smart lyrics, book, and inventive vocal arrangements, brilliantly joins isolation with live harmony. It’s really something.

And helmed by David Muse, “Octet” is a precisely, quietly, yet powerfully staged production, featuring a topnotch cast who (when not taking their moment in the spotlight) use their voices to make sounds and act as a sort of Greek chorus. Mostly on stage throughout all of the 100-minute one act, they demonstrate impressive stamina and concentration.

An immersive production, “Octet” invites audience members to feel a part of the meeting. Studio’s Shargai Theatre is configured, for the first, in the round. And like the characters, patrons must also unplug. Everyone is required to have their phones locked in a small pouch (that only ushers are able to open and close), so be prepared for a wee bit of separation anxiety.

At the end of the meeting, the group surrenders somnambulantly. They know they are powerless against internet addiction. But group newbie Velma (Amelia Aguilar) isn’t entirely convinced. She remembers the good tech times.

In a bittersweet moment, she shares of an online friendship with “a girl in Sainte Marie / Just like me.”

Habits aren’t easily shaken.

Theater

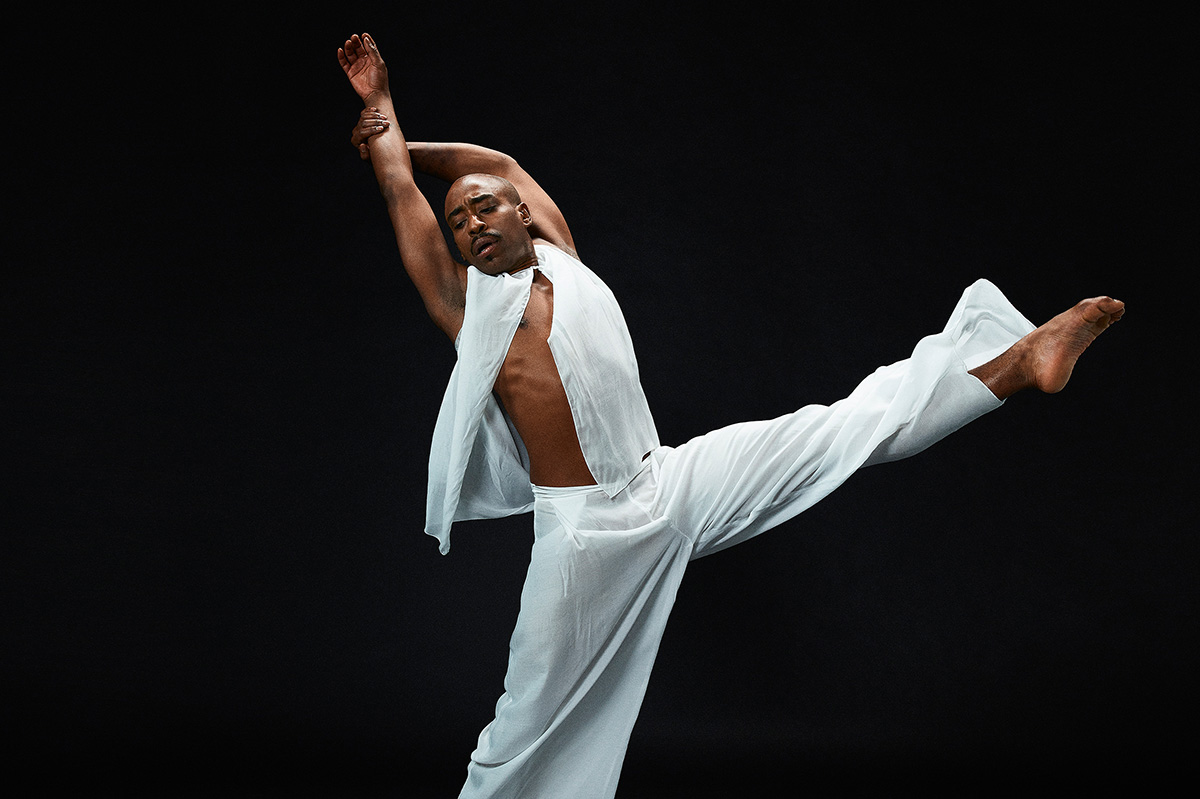

Out dancer on Alvin Ailey’s stint at Warner Theatre

10-day production marks kickoff of national tour

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Through Feb. 8

Warner Theatre

513 12th St., N.W.

Tickets start at $75

ailey.org

The legendary Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is coming to Washington’s Warner Theatre, and one of its principal veterans couldn’t be more pleased. Out dancer Renaldo Maurice is eager to be a part of the company’s 10-day stint, the kickoff of a national tour that extends through early May.

“I love the respectful D.C. crowd and they love us,” says Maurice, a member of esteemed modern dance company for 15 years. The traveling tour is made of two programs and different casting with Ailey’s masterwork “Revelations” in both programs.

Recently, we caught up with Maurice via phone. He called from one of the quiet rooms in his New York City gym where he’s getting his body ready for the long Ailey tour.

Based in North Newark, N.J., where he recently bought a house, Maurice looks forward to being on the road: “I enjoy the rigorous performance schedule, classes, shows, gym, and travel. It’s all part of carving out a lane for myself and my future and what that looks like.”

Raised by a single mother of three in Gary, Ind., Maurice, 33, first saw Alvin Ailey as a young kid in the Auditorium Theatre in downtown Chicago, the same venue where he’s performed with the company as a professional dancer.

He credits his mother with his success: “She’s a real dance mom. I would not be the man or artist I am today if it weren’t for the grooming and discipline of my mom. Support and encouragement. It’s impacted my artistry and my adulthood.”

Maurice is also part of the New York Ballroom scene, an African-American and Latin underground LGBTQ+ subculture where ball attendees “walk” in a variety of categories (like “realness,” “fashion,” and “sex siren”) for big prizes. He’s known as the Legendary Overall Father of the Haus of Alpha Omega.

WASHINGTON BLADE: Like many gay men of his era, Ailey lived a largely closeted public life before his death from AIDS-related complications in 1989.

RENALDO MAURICE Not unusual for a Black gay man born during the Depression in Rogers, Texas, who’s striving to break out in the industry to be a creative. You want to be respected and heard. Black man, and Black man who dances, and you may be same-sex gender loving too. It was a lot, especially at that time.

BLADE: Ailey has been described as intellectual, humble, and graceful. He possessed strength. He knew who he was and what stories he wanted to tell.

MAURICE: Definitely, he wanted to concentrate on sharing and telling stories. What kept him going was his art. Ailey wanted dancers to live their lives and express that experience on stage. That way people in the audience could connect with them. It’s incredibly powerful that you can touch people by moving your body.

That’s partly what’s so special about “Revelations,” his longest running ballet and a fan favorite that’s part of the upcoming tour. Choreographed by Alvin Ailey in 1960, it’s a modern dance work that honors African-American cultural heritage through themes of grief, joy, and faith.

BLADE: Is “Revelation” a meaningful piece for you?

MAURICE: It’s my favorite piece. I saw it as a kid and now perform it as a professional dance artist. I’ve grown into the role since I was 20 years old.

BLADE: How can a dancer in a prestigious company also be a ballroom house father?

MAURICE: I’ve made it work. I learned how to navigate and separate. I’m a principal dancer with Ailey. And I take that seriously. But I’m also a house father and I take that seriously as well.

I’m about positivity, unity, and hard work. In ballroom you compete and if you’re not good, you can get chopped. You got to work on your craft and come back harder. It’s the same with dance.

BLADE: Any message for queer audiences?

MAURICE: I know my queer brothers and sisters love to leave with something good. If you come to any Ailey performance you’ll be touched, your spirit will be uplifted. There’s laughter, thoughtful and tender moments. And it’s all delivered by artists who are passionate about what they do.

BLADE: Alvin Ailey has been a huge part of your life. Thoughts on that?

MAURICE: I’m a believer in it takes a village. Hard work and discipline. I take it seriously and I love what I do. Ailey has provided me with a lot: world travel, a livelihood, and working with talented people here and internationally. Alvin Ailey has been a huge part of my life from boyhood to now. It’s been great.

-

Virginia3 days ago

Virginia3 days agoMcPike wins special election for Va. House of Delegates

-

New York5 days ago

New York5 days agoPride flag removed from Stonewall Monument as Trump targets LGBTQ landmarks

-

Florida5 days ago

Florida5 days agoDisney’s Gay Days ‘has not been canceled’ despite political challenges

-

Philippines5 days ago

Philippines5 days agoPhilippines Supreme Court rules same-sex couples can co-own property