Movies

SPRING ARTS 2017: movies — Festivals, series and a ‘Beast’ remake

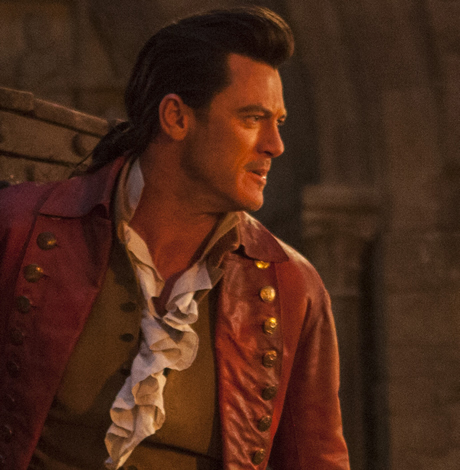

Live-action Disney reboot features gays galore

Out actor Luke Evans as Gaston in ‘Beauty and the Beast,’ a live-action remake of the Disney classic. (Photo courtesy Walt Disney Studios)

The biggest and queerest release of the 2017 spring movie season is Disney’s live-action “Beauty and the Beast.” Based on the classic 1991 animated movie, this version uses CGI to bring the enchanted objects to captivating life. Dan Stevens (“Downtown Abbey”) and Emma Watson (all those Harry Potter movies) play the title couple; Emma Thompson sings the title song.

Besides a substantial LGBT fanbase, the new release has a significant gay pedigree. The late Howard Ashman (“Little Shop of Horrors”) wrote the lyrics for the songs in the animated movie. (Alan Menken composed the score and Tim Rice wrote the additional lyrics.) The film is helmed by Bill Condon (“Dreamgirls” and “Gods and Monsters”), who’s openly gay as are actors Luke Evans as Gaston and Ian McKellen as Cogsworth.

No word yet on a D.C. screening, but “The Freedom to Marry,” a documentary from Eddie Rosenstein that features Evan Wolfson (long-time marriage activist) and attorney Mary Bonauto is in theaters now in New York and slated to open next weekend in Los Angeles. Details at freedomtomarrymovie.com.

Also on the marriage front is “Love v. Kentucky,” released in February and streaming now on Amazon, iTunes and others. It’s billed as an “intimate account of how two Kentucky attorneys with no background in vivil rights navigate their passionate opponenets and wrangle their reluctant allies” to the U.S. Supreme Court. Alex Schuman directs. Details at lovevkentucky.com.

The D.C. Shorts Film Festival & Screenplay Competition returns in September, but the team has two events coming up this spring. In March, the MENTORS Series will offer workshops for filmmakers. In April, the D.C. Shorts LAUGHS program will pair local comedians with funny films from past festivals. One of the funniest matches will be between Matty Litwack and “The Bench Project: Lost and Found,” a film with a delightful gay twist. Details pending. Check back later at laughs.dcshorts.com for details.

This spring, Reel Affirmations offers an exciting slate of films through XTRA, its monthly LGBT Film Series. Friday, March 24 offers the newly released “BWOY” and the 20th anniversary screening of “Watermelon Woman.” Directed by Sundance sensation John G. Young and starring Anthony Rapp, “BWOY” tells the story of a man rebuilding his life after the death of his son. In “Watermelon Woman,” writer/director/star Cheryl Dunye creates a fascinating fictional documentary about the (nonexistent) history of African-American women on film.

On Friday, April 21, XTRA tells the story of Ugandan transgender activist Cleopatra Kambugu in “The Pearl of Africa.” “The First Girl I Loved” (Friday, May 12) is a remarkable lesbian coming-of-age story that won the “Best of Next!” Award at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival. And on Friday, June 16, the screening room turns into a ballroom for “Kiki,” the new documentary described as a sequel to “Paris Is Burning” that captures the youth-led expansion of New York City’s ballroom scene.

In addition, Reel Affirmations will host the Reel Trans Film Festival on Saturday, May 20 at the Studio Theatre. Miss Major Griffin-Gracy will be on hand to discuss a documentary about her revolutionary life.

Several other regional film festivals will also bloom this spring. While they haven’t announced their 2017 schedules as of press time, they have all been included rich LGBT fare in recent years. The Annapolis Film Festival runs March 30-April 2 and the Washington Jewish Film Festival runs from May 17-28.

Filmfest D.C. runs April 20-30 and will include “Play the Devil,” a thrilling coming-of-age story set in Trinidad. Organizers promise more information soon.

Legendary filmmaker and Baltimore native John Waters, recently presented with the Timeless Star Dorian Award by the Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, is staying mum about the film he will be hosting for the 2017 Maryland Film Festival which runs in Baltimore May 3-7. He and a slate of exciting films will be on hand to welcome guests to the revitalized SNF Parkway Film Center (5 W. North Ave., Baltimore).

AFI Silver in downtown Silver Spring, Md., continues to present the latest indie films from around the world, along with curated explorations of classic films from Hollywood and international cinema. A highlight of their spring schedule is All About Almodóvar which runs March 4-April 27. The tribute to the legendary queer Spanish director includes a wide sampling of his films from his early anarchic films released in the heady days after the fall of Franco (“Labyrinth of Passion”) to his delicious delirious farces (“I’m So Excited”) to his more recent melodramas (“Volver”).

A special evening for dedicated Almodóvar fans will be the double bill of “Matador” (1986) and “Law of Desire” (1987) on Tuesday, March 21. Both films feature outstanding performances by a young Antonio Banderas and Almodóvar muse Carmen Maura.

For the whole family, AFI offer series on the Muppets (March 4-April 23) and the Marx Brothers (March 24-April 20). There’s also a centennial tribute to actor Kirk Douglas who founded a Hollywood dynasty while helping to break the Hollywood Blacklist in the 1950s.

Also at the AFI, “Little Men,” the moving story about a budding bromance between two Brooklyn teens by openly gay director Ira Sachs (“Keep the Lights On”), will screen March 6-9. Also look for the director’s cut of the dystopic “Blade Runner” (March 31-April 2), John Hurt and Richard Burton in “1984” (April 20) and Angela Lansbury’s terrifying performance in “The Manchurian Candidate” (April 23 and 26). Lighter fare includes the steamy “Ramen Western” “Tampopo” (April 2) and Mel Brooks’ comic masterpiece “Blazing Saddles” from April 7-9.

One of the few studio releases with queer content this spring is “Raw” which opens on Friday, March 24. Some audience members at Cannes and the Toronto Film Festival fled the theater during the screening, but others hailed the first feature film by French director Julie Ducournau for its confidence and decadent style. The plot centers on a college freshman (Garance Marillier) whose life changes when a bizarre hazing ritual awakens sexual and culinary appetites in the former vegetarian.

On Friday, April 7, Landmark E Street Cinema is host to bad boy French director François Ozon. In a departure for the openly gay director, “Frantz” offers a somber tale about the aftermath of World War I set in the quiet German countryside and shot in black and white.

From April 21-23, Dan Savage’s HUMP! Film Festival comes to the Black Cat (1811 14th St., N.W.). HUMP! is a celebration of sexual expression that includes an amazingly diverse array of short amateur porn videos.

Some mainstream releases of note include:

• “The Last Word” (March 10) with Shirley MacLaine as a retired businesswoman who hires Amanda Seyfried to write her life story.

• “T2 Trainspotting” (March 24), reunites the original stars in a sequel to the classic 1996 movie.

• “Song to Song” (March 24) stars Ryan Gosling, Rooney Mara, Michael Fassbender and Natalie Portman’s as two entangled couples in Terence Malick’s tale of seduction and betrayal set against the backdrop of Austin’s contemporary music scene.

• “Unforgettable” (April 21) stars Katherine Heigl in a dramatic turn as Tessa Connover, a woman who becomes obsessed with her ex-husband’s new wife (Rosario Dawson).

Just in time for Mother’s Day, the cinematic mother-daughter team of Amy Schumer and Goldie Hawn romp their way through “Snatched” (May 12). The comedy is scripted by Katie Dippold, who wrote last year’s “Ghostbusters” remake, and features lesbian comic Wanda Sykes.

Goldie Hawn, left, makes a welcome return to the big screen with ’SNATCHED,’ with Amy Schumer. It’s her first major role since 2002. (Photo courtesy Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.)

And on the superhero front, there are some major entrances and exits coming this spring. On Friday, March 3, longtime LGBT ally Hugh Jackman steps away from the Wolverine franchise in “Logan.” On Friday, June 2, Gal Gadot grabs the golden lasso for her first solo feature film as “Wonder Woman.” And on a lighter note, Groot and the gang return in “Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2” on May 5.

And for those who don’t have regular access to theaters that screen LGBT-affirming works or if you just want to someone else to curate a series for you, check out Frameline, a San Francisco-based media arts non-profit that releases LGBT-affirming films monthly on its YouTube channel. Search “Frameline” on YouTube to find out more. About 50 films hosted over the last five years are available for viewing there.

The fifth annual D.C. Web Fest is Saturday, April 1 from 4-11 p.m. featuring web series, online short films, apps and online games.

Movies

Moving doc ‘Come See Me’ is more than Oscar worthy

Poet Laureate Andrea Gibson, wife negotiate highs and lows of terminal illness

When Colorado Poet Laureate Andrea Gibson died from ovarian cancer in the summer of 2025, the news of their passing may have prompted an outpouring of grief from their thousands of followers on social media, but it was hardly a surprise.

That’s because Gibson – who had risen to both fame and acclaim in the early 2000s with intense live performances of their work that made them a “superstar” at Poetry Slam events – had been documenting their health journey on Instagram ever since receiving the diagnosis in 2021. During the process, they gained even more followers, who were drawn in by the reflections and explorations they shared in their daily posts. It was really a continuation, a natural evolution of their work, through which their personal life had always been laid bare, from the struggles with queer sexuality and gender they experienced in their youth to the messy relationships and painful breakups of their adult life; now, with precarious health prohibiting a return to the stage, they had found a new platform from which to express their inner experience, and their fans – not only the queer ones for whom their poetry and activism had become a touchstone, but the thousands more who came to know them through the deep shared humanity that exuded through their online presence – were there for it, every step of the way.

At the same time, and in that same spirit of sharing, there was another work in progress around Gibson: “Come See Me in the Good Light,” a film conceived by their friends Tig Notaro and Stef Willen and directed by seasoned documentarian Ryan White (“Ask Dr. Ruth”, “Good Night, Oppy”, “Pamela, a Love Story”), it was filmed throughout 2024, mostly at the Colorado home shared by Gibson and their wife, fellow poet Megan Falley, and debuted at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival before a release on Apple TV in November. Now, it’s nominated for an Academy Award.

Part life story, part career retrospective, and part chronicle of Gibson and Falley’s relationship as they negotiate the euphoric highs and heartbreaking lows of Gibson’s terminal illness together, it’s not a film to be approached without emotional courage; there’s a lot of pain to be vicariously endured, both emotional and physical, a lot of hopeful uplifts and a lot of crushing downfalls, a lot of spontaneous joy and a lot of sudden fear. There’s also a lot of love, which radiates not only from Gibson and Falley’s devotion and commitment to being there for each other, no matter what, but through the support and positivity they encounter from the extended community that surrounds them. From their circle of close friends, to the health care professionals that help them navigate the treatment and the difficult choices that go along with it, to the extended family represented by the community of fellow queer artists and poets who show up for Gibson when they make a triumphant return to the stage for a performance that everyone knows may well be their last, nobody treats this situation as a downer. Rather, it’s a cause to celebrate a remarkable life, to relish friendship and feelings, to simply be present and embrace the here and now together, as both witness and participant.

At the same time, White makes sure to use his film as a channel for Gibson’s artistry, expertly weaving a showcase for their poetic voice into the narrative of their survival. It becomes a vibrant testament to the raw power of their work, framing the poet as a seminal figure in a radical, feminist, genderqueer movement which gave voice to a generation seeking to break free from the constraints of a limited past and imagine a future beyond its boundaries. Even in a world where queer existence has become – yet again – increasingly perilous in the face of systemically-stoked bigotry and bullying, it’s a blend that stresses resilience and self-empowerment over tragedy and victimhood, and it’s more than enough to help us find the aforementioned emotional courage necessary to turn what is ultimately a meditation on dying into a validation of life.

That in itself is enough to make “Come See Me in the Good Light” worthy of Oscar gold, and more than enough to call it a significant piece of queer filmmaking – but there’s another level that distinguishes it even further.

In capturing Gibson and Falley as they face what most of us like to think of as an unimaginable future, White’s quietly profound movie puts its audience face-to-face with a situation that transcends all differences not only of sexuality or gender, but of race, age, or economic status as well. It confronts us with the inevitability few of us are willing to consider until we have to, the unhappy ending that is rendered certain by the joyful beginning, the inescapable conclusion that has the power to make the words “happily ever after” feel like a hollow promise. At the center of this loving portrait of a great American artist is a universal story of saying goodbye.

Yes, there is hope, and yes, good fortune often prevails – sometimes triumphantly – in the ongoing war against the cancer that has come to threaten the palpably genuine love this deeply-bonded couple has found together; but they (and we) know that, even in the best-case scenario, the end will surely come. All love stories, no matter how happy, are destined to end with loss and sorrow; it doesn’t matter that they are queer, or that their gender identities are not the same as ours – what this loving couple is going through, together, is a version of the same thing every loving couple lucky enough to hold each other for a lifetime must eventually face.

That they meet it head on, with such grace and mutual care, is the true gift of the movie.

Gibson lived long enough to see the film’s debut at Sundance, which adds a softening layer of comfort to the knowledge we have when watching it that they eventually lost the battle against their cancer; but even if they had not, what “Come See Me in the Good Light” shows us, and the unflinching candor with which it does so, delivers all the comfort we need.

Whether that’s enough to earn it an Oscar hardly matters, though considering the notable scarcity of queer and queer-themed movies in this year’s competition it might be our best shot at recognition.

Either way, it’s a moving and celebratory film statement with the power to connect us to our true humanity, and that speaks to a deeper experience of life than most movies will ever dare to do.

Movies

Radical reframing highlights the ‘Wuthering’ highs and lows of a classic

Emerald Fennell’s cinematic vision elicits strong reactions

If you’re a fan of “Wuthering Heights” — Emily Brontë’s oft-filmed 1847 novel about a doomed romance on the Yorkshire moors — it’s a given you’re going to have opinions about any new adaptation that comes along, but in the case of filmmaker Emerald Fennell’s new cinematic vision of this venerable classic, they’re probably going to be strong ones.

It’s nothing new, really. Brontë’s book has elicited controversy since its first publication, when it sparked outrage among Victorian readers over its tragic tale of thwarted lovers locked into an obsessive quest for revenge against each other, and has continued to shock generations of readers with its depictions of emotional cruelty and violent abuse, its dysfunctional relationships, and its grim portrait of a deeply-embedded class structure which perpetuates misery at every level of the social hierarchy.

It’s no wonder, then, that Fennell’s adaptation — a true “fangirl” appreciation project distinguished by the radical sensibilities which the third-time director brings to the mix — has become a flash point for social commentators whose main exposure to the tale has been flavored by decades of watered-down, romanticized “reinventions,” almost all of which omit large portions of the novel to selectively shape what’s left into a period tearjerker about star-crossed love, often distancing themselves from the raw emotional core of the story by adhering to generic tropes of “gothic romance” and rarely doing justice to the complexity of its characters — or, for that matter, its author’s deeper intentions.

Fennell’s version doesn’t exactly break that pattern; she, too, elides much of the novel’s sprawling plot to focus on the twisted entanglement between Catherine Earnshaw (Margot Robbie), daughter of the now-impoverished master of the titular estate (Martin Clunes), and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi), a lowborn child of unknown background origin that has been “adopted” by her father as a servant in the household. Both subjected to the whims of the elder Earnshaw’s violent temper, they form a bond of mutual support in childhood which evolves, as they come of age, into something more; yet regardless of her feelings for him, Cathy — whose future status and security are at risk — chooses to marry Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif), the financially secure new owner of a neighboring estate. Heathcliff, devastated by her betrayal, leaves for parts unknown, only to return a few years later with a mysteriously-obtained fortune. Imposing himself into Cathy’s comfortable-but-joyless matrimony, he rekindles their now-forbidden passion and they become entwined in a torrid affair — even as he openly courts Linton’s naive ward Isabella (Alison Oliver) and plots to destroy the entire household from within. One might almost say that these two are the poster couple for the phrase “it’s complicated.” and it’s probably needless to say things don’t go well for anybody involved.

While there is more than enough material in “Wuthering Heights” that might easily be labeled as “problematic” in our contemporary judgments — like the fact that it’s a love story between two childhood friends, essentially raised as siblings, which becomes codependent and poisons every other relationship in their lives — the controversy over Fennell’s version has coalesced less around the content than her casting choices. When the project was announced, she drew criticism over the decision to cast Robbie (who also produced the film) opposite the younger Elordi. In the end, the casting works — though the age gap might be mildly distracting for some, both actors deliver superb performances, and the chemistry they exude soon renders it irrelevant.

Another controversy, however, is less easily dispelled. Though we never learn his true ethnic background, Brontë’s original text describes Heathcliff as having the appearance of “a dark-skinned gipsy” with “black fire” in his eyes; the character has typically been played by distinctly “Anglo” men, and consequently, many modern observers have expressed disappointment (and in some cases, full-blown outrage) over Fennel’s choice to use Elordi instead of putting an actor of color for the part, especially given the contemporary filter which she clearly chose for her interpretation for the novel.

In fact, it’s that modernized perspective — a view of history informed by social criticism, economic politics, feminist insight, and a sexual candor that would have shocked the prim Victorian readers of Brontë’s novel — that turns Fennell’s visually striking adaptation into more than just a comfortably romanticized period costume drama. From her very opening scene — a public hanging in the village where the death throes of the dangling body elicit lurid glee from the eagerly-gathered crowd — she makes it oppressively clear that the 18th-century was not a pleasant time to live; the brutality of the era is a primal force in her vision of the story, from the harrowing abuse that forges its lovers’ codependent bond, to the rigidly maintained class structure that compels even those in the higher echelons — especially women — into a kind of slavery to the system, to the inequities that fuel disloyalty among the vulnerable simply to preserve their own tenuous place in the hierarchy. It’s a battle for survival, if not of the fittest then of the most ruthless.

At the same time, she applies a distinctly 21st-century attitude of “sex-positivity” to evoke the appeal of carnality, not just for its own sake but as a taste of freedom; she even uses it to reframe Heathcliff’s cruel torment of Isabella by implying a consensual dom/sub relationship between them, offering a fragment of agency to a character typically relegated to the role of victim. Most crucially, of course, it permits Fennell to openly depict the sexuality of Cathy and Heathcliff as an experience of transgressive joy — albeit a tormented one — made perhaps even more irresistible (for them and for us) by the sense of rebellion that comes along with it.

Finally, while this “Wuthering Heights” may not have been the one to finally allow Heathcliff’s ambiguous racial identity to come to the forefront, Fennell does employ some “color-blind” casting — Latif is mixed-race (white and Pakistani) and Hong Chau, understated but profound in the crucial role of Nelly, Cathy’s longtime “paid companion,” is of Vietnamese descent — to illuminate the added pressures of being an “other” in a world weighted in favor of sameness.

Does all this contemporary hindsight into the fabric of Brontë’s epic novel make for a quintessential “Wuthering Heights?” Even allowing that such a thing were possible, probably not. While it presents a stylishly crafted and thrillingly cinematic take on this complex classic, richly enhanced by a superb and adventurous cast, it’s not likely to satisfy anyone looking for a faithful rendition, nor does it reveal a new angle from which the “romance” at its center looks anything other than toxic — indeed, it almost fetishizes the dysfunction. Even without the thorny debate around Heathcliff’s racial identity, there’s plenty here to prompt purists and revisionists alike to find fault with Fennell’s approach.

Yet for those looking for a new window into to this perennial classic, and who are comfortable with the radical flourish for which Fennell is already known, it’s an engrossing and intellectually stimulating exploration of this iconic story in a way that exchanges comfortable familiarity for unpredictable chaos — and for cinema fans, that’s more than enough reason to give “Wuthering Heights” a chance.

Movies

As Oscars approach, it’s time to embrace ‘KPop Demon Hunters’

If you’ve resisted it, now’s the time to give in

If you’re one of the 500 million people who made “KPop Demon Hunters” into the most-watched original Netflix title in the streaming platform’s history, this article isn’t for you.

If, however, you’re one of the millions who skipped the party when the Maggie Kang-created animated musical fantasy debuted last summer, you might be wondering why this particular piece of pop youth culture is riding high in an awards season that seems all but certain to end with it winning an Oscar or two; and if that’s the case, by all means, keep reading.

We get it. If you’re not a young teen (or you don’t have one), it might have escaped your radar. If you don’t like KPop, or the fantasy genre just isn’t your thing, there would be no reason for that title to pique your interest – on the contrary, you would assume it’s just a movie that wasn’t made for you and leave it at that.

It’s now more than half a year later, though, and “KPop Demon Hunters” has yet to fade into pop culture memory, in spite of the “new, now, next” pace with which our social media world keeps scrolling by. It might feel like there’s been a resurgence of interest since the film’s ongoing sweep of major awards in the Best Animated Film and Best Song categories has led it close to Oscar gold, but in reality, the interest never really flagged. Millions of fans were still streaming the soundtrack album on a loop, all along.

It wasn’t just the music that they embraced, though that was definitely a big factor – after all, the film’s signature song, “Golden,” has now landed a Grammy to display alongside all of its film industry accolades. But Kang’s anime-influenced urban fantasy taps into something more substantial than the catchiness of its songs; through the filter of her experience as a South Korean immigrant growing up in Canada, she draws on the traditions and mythology of her native culture while blending them seamlessly into an infectiously contemporary and decidedly Western-flavored “girl power” adventure about an internationally popular KPop girl band – Huntrix, made up of lead singer Rumi (Arden Cho), lead dancer Mira (May Hong), and rapper/lyricist Zoey (Ji-young Yoo) – who also happen to be warriors, charged with protecting humankind from the influence of Gwi-Ma (Lee Byung-hun), king of the demon world, which is kept from infiltrating our own by the power of their music and their voices. Oh, and also by their ability to kick demon ass.

In an effort to defeat the girls at their own game, Gwi-Ma sends a demonic boy band led by handsome human-turned-demon Jinu (Ahn Hyo-seop) to steal their fans, creating a rivalry that (naturally) becomes complicated by the spark that ignites between Rumi and Jinu, and that forces Rumi to confront the half-demon heritage she has managed to keep secret – even from her bandmates – but now threatens to destroy Huntrix from within, just when their powers are needed most.

It’s a bubble-gum flavored fever-dream of an experience, for the most part, which never takes itself too seriously. Loaded with outrageous kid-friendly humor and pop culture parody, it might almost feel as if it were making fun of itself if not for the obvious sincerity it brings to its celebration of all things K-Pop, and the tangible weight it brings along for the ride through its central conflict – which is ultimately not between the human and demon worlds but between the long-held prejudices of the past and the promise of a future without them.

That’s the hook that has given “KPop Demon Hunters” such a wide-ranging and diverse collection of fans, and that makes it feel like a well-timed message to the real world of the here and now. In her struggle to come to terms with her part-demon nature – or rather, the shame and stigma she feels because of it – Rumi becomes a point of connection for any viewer who has known what it’s like to hide their full selves or risk judgment (or worse) from a world that has been taught to hate them for their differences, and maybe what it’s like to be taught to hate themselves for their differences, too.

For obvious reasons, that focus adds a strong layer of personal relevance for queer audiences; indeed, Kane has said she wanted the film to mirror a “coming out” story, drawing on parallels not just with the LGBTQ community, but with people marginalized through race, gender, trauma, neurodivergence – anything that can lead people to feel like an “other” through cultural prejudices and force them to deal with the pressure of hiding an essential part of their identity in order to blend in with the “normal” community. It plays like a direct message to all who have felt “demonized” for something that’s part of their nature, something over which they have no choice and no control, and it positions that deeply personal struggle as the key to saving the world.

Of course, “KPop Demon Hunters” doesn’t lean so hard into its pro-diversity messaging that it skimps on the action, fun, and fantasy that is always going to be the real reason for experiencing a genre film where action, fun, and fantasy are the whole point in the first place. You don’t have to feel like an “other” to enjoy the ride, or even to get the message – indeed, while it’s nice to feel “seen,” it’s arguably much more satisfying to know that the rest of the world might be learning how to “see” you, too. By the time it reaches its fittingly epic finale, Kane’s movie (which she co-directed with Chris Appelhans, and co-wrote with Appelhans, Danya Jimenez, and Hannah McMechan) has firmly made its point that, in a community threatened by hatred over perceived differences, the real enemy is our hate – NOT our differences.

Sure, there are plenty of other reasons to enjoy it. Visually, it’s an imaginative treat, building an immersive world that overlays an ancient mythic cosmology onto a recognizably contemporary setting to create a kind of whimsical “metaverse” that feels almost more real than reality (the hallmark of great mythmaking, really); yet it still allows for “Looney Toons” style cartoon slapstick, intricately choreographed dance and battle sequences that defy the laws of physics, slick satirical commentary on the juggernaut of pop music and the publicity machine that drives it, not to mention plenty of glittery K-Pop earworms that will take you back to the thrill of being a hormonal 13-year-old on a sugar high; but what makes it stand out above so many similar generic offerings is its unapologetic celebration of the idea that our strength is in our differences, and its open invitation to shed the shame and bring your differences into the light.

So, yes, you might think “KPop Demon Hunters” would be a movie that’s exactly what it sounds like it will be – and you’d be right – but it’s also much, much more. If you’ve resisted it, now’s the time to give in.

At the very least, it will give you something else to root for on Oscar night.