a&e features

‘Call Me By Your Name’ author Andre Aciman talks shop

Straight novelist says most of his friends, interests in life have been gay

The PEN/Faulkner Foundation presents:

‘Call Me By Your Name: an Evening with Andre Aciman’

Friday, April 20

GW Lisner Auditorium

730 21st St., N.W.

7 p.m.

general admission: $20

admission, book & signing: $35

Luca Guadagnino (left) and André Aciman at a screening of ‘Call Me By Your Name’ at the 2017 Berlin International Film Festival. Aciman made a cameo in the film as one of Elio’s parents’ gay friends. (Photo by Franz Richter via Wikimeda)

Not only are actors Armie Hammer and Timothee Chalamet — leads in the seminal gay coming-of-age movie “Call Me By Your Name,” — straight, Andre Aciman, author of the 2007 novel upon which its based, is straight as well.

He’ll be in Washington on Friday, April 20 for a moderated discussion at the Lisner Auditorium hosted by the PEN/Faulkner Foundation, which the Atlantic’s Spencer Kornhaber will moderate. He spoke to the Blade this week by phone from his New York home base where he writes and teaches comparative literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. His comments have been slightly edited for length.

WASHINGTON BLADE: Are you tired of talking about “Call Me By Your Name?”

ANDRE ACIMAN: It’s been part of my life for the past 10 years and any opportunity I have to talk, I seize it because I love it. It hasn’t become either habitual or tedious yet and I don’t see it happening. It’s been fantastic for the past year since the movie came out but also for the past 10 years when the book was initially released to quite a bit of acclaim although it was never a bestseller.

BLADE: Did gays embrace it right away or later with the movie tie-in?

ACIMAN: It was immediately read. I’m actually writing a piece on that. Initially I received a lot of mail from people into their 80s who were extremely moved by the story and at the bottom of their e-mail there was always something like I wish my father had been there to give me that kind of a talk. So yes, what they were all lamenting was the fact that the coming-out ritual, which is now so palpable everywhere, it didn’t really exist in those years so they couldn’t even really come out. There was nothing to come out with as it were so you had to keep it under wraps.

BLADE: I know a lot of people found the father’s speech very moving but I felt it worked better in the book. The movie felt so minimalist and languid then the speech to me felt suddenly quite literal and even a bit patronizing. Like suddenly it turned into an after-school special. I’m guessing you would disagree with that but it was the one moment in the movie that felt a bit false to me. I didn’t feel that in the book.

ACIMAN: Well I don’t know if it’s a fair criticism but I know when people read that speech they cry to begin with and when they hear it said in the movie they cry again. In other words, the crying begins with the father’s speech and not necessarily with the separation of the two guys. It was quite easy to write and it basically came out rather spontaneously. The way it was, I caught myself writing a sentence like “to feel nothing in order to feel nothing.” Where do you get double negatives like that in a write who sort of watches his language, but I left it that way because I figured this captured what I was trying to say. The difficult part was not that, but writing the scene where Elio sort of blubbers or sort of without thinking ends up telling Oliver what he feels. That was very difficult to write because I didn’t want him to come out and say it. I wanted it to be as ambiguous as possible so he’d have some chance of retraction if it was going to be embarrassing.

BLADE: You’ve said in other interviews you’re perplexed when people tell you they cry at the book or the movie. Are you being self-effacing perhaps? It’s a poignant story. That it would induce tears does not seem surprising to me.

ACIMAN: I was perplexed by it. Yes, everything about me is modesty so I have to assume, without knowing of course, I have to even assume some of it will be affected. I’m willing to grant that much. On the other hand, the one moment that was moving to me — not to tears, but it was just, I could feel a sort of shudder running through me when I decided to write the scene — was the moment when Elio says toward the end of the book that whenever he passes by that wall where they kissed rather passionately, he still feels the presence of that kiss. For me that was very moving and very true but I doubt anybody cried in that moment because it wasn’t anything that sort of brings tears to your eyes. … Also when Oliver tells him, “I remember everything,” I could see where that could be moving, but it’s not a sad crying. That’s what perplexes me. People tell me they cried for days. I always ask them to tell me why and nobody can explain it.

BLADE: Don’t you think it’s as simple as them being startled that you captured feelings so well they’d previously felt themselves?

ACIMAN: Well maybe that’s the part I don’t understand totally. I do understand it partly. … What I don’t understand is you haven’t read this all over the place? Am I the only one who does this and many people say yes. I can’t believe this because, well, among other things there’s Marcel Proust, the great Michelangelo of the psychological book. (Editor’s note: Aciman is editor of “The Proust Project.”)

BLADE: Oliver and Elio are both intellectuals or at least budding intellectuals perhaps for Elio. Would the story have worked if they’d had average IQs or were more blue collar?

ACIMAN: If they had lower IQs or were less educated, I would not have been interested in them at all. The fact that Elio is already precocious is part of what I was at his age. I had read everything almost by the time I was 17. I knew classical music, I loved the high arts and yes, I was a bit elitist and still am. In many respects if they were the working class sort or if it had been some kind of gas station love affair where they did it in the bathroom or whatever, I have no interest in that and it doesn’t even eroticize me. … I’m not interested in class differentiation, the sort of pedestrian lifestyle or what you’d call the average man. I’ve never been interested in average people.

BLADE: Could it have worked if they’d been a straight couple?

ACIMAN: I think it would have worked the same exact way. The fact that Oliver tells him this is all wrong, that’s exactly what an older tutor type would say if the guy had a crush on his tutor, she would say, “No, this is wrong, I’m your dad’s employee, I don’t want to do this.” The other aspect is that it starts with a very physical and brutal infatuation. It could be a girl and a girl as far as I’m concerned. The fact that Elio is so embarrassed is not because it’s a gay love. It’s because he’s so attracted to him. Attraction is not something, of course it’s very natural physically speaking, but in society, it’s not exactly the kind of thing one wants to let on that one feels … but not because it’s gay.

BLADE: Was it a hard sell?

ACIMAN: Oh, you mean you don’t know? I was writing another novel and I had stopped writing it because it was giving me such a hard time. And then I just wrote “Call Me By Your Name” in three-and-a-half months. So I went to my agent’s office and I said I had finished a novel and she said, “Oh, you finally finished it,” it was going on three years. I said, “No, I wrote a new novel.” … She wrote to me early the next morning saying she had read it overnight and she loved it and wanted to sell it and it was sold within 24 hours. Jonathan Galassi (president of publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux) read it very, very quickly and he knew, I think, that he felt it was the right thing for them and he bought it right away. (Note: the other book he was working on was eventually published — “Eight White Nights” in 2010.)

BLADE: You held firm to your ending although you were very open to other editing. Did you have final cut in your contract and if so, how common or uncommon is that in the publishing world?

ACIMAN: It’s more of a courtesy relationship. They make recommendations. If you absolutely refuse, they’ll go along with it. Jonathan Galassi is known to say to people, “It’s your book.” In other words, you can do what you want. But he did make suggestions and I did cut some things. The chapter in Rome was originally about twice its size. It was very long because I was enjoying myself at that point. They had had sex, everything was on the table so I could just go with this honeymoon trip to Rome and have a great deal of fun with it. I wanted them to go to the cemetery where John Keats is buried but I figured we’ll cut this and it was fine. It made perfect sense to cut except when I feel, maybe five-10 percent of the time what I had in place was correct.

BLADE: Tell us about the PEN/Faulkner event. Will you be interviewed?

ACIMAN: Yes but that’s all I know. I don’t know what the questions are and I always want to be surprised and think on my feet. But it’s flattering that they invited me and I’m very pleased.

BLADE: When the movie came out, did you attend many of the film festivals and press junkets?

ACIMAN: No. I just went to the one in Berlin and the New York one. When you’re a writer, you’re an extra in the mix. People want to see the movie stars. They’re sexy figures at this point and that’s what people want to see. They don’t need the intellectual to sort of narrate his own work. It’s not that interesting.

BLADE: Was there any talk of possibly you adapting the screenplay before James Ivory got involved?

ACIMAN: I don’t think there was. I’m not really trained in that although I could do it. I didn’t want to put my energies into something like that while I was writing another book. I think James Ivory did a fantastic job altogether and (director) Luca (Guadagnino) also because when you’re filming something there are changes you make to the script all the time.

BLADE: Did you know Luca’s work before this got optioned?

ACIMAN: Yes and I was extremely happy because I had seen a few years earlier the film “I Am Love,” which I particularly liked.

BLADE: Have you known many gay people throughout your life?

ACIMAN: Oh god yes, many. In fact I would say most of my friends, my best friends are gay. Not all, but most. I tend not to write alpha male types. They’re not something I can speak with about the life of the mind, the life of the soul. Gay people tend to be much more open to those sorts of touchy subjects and I found myself more interested in discussing those things.

BLADE: Did you listen to Armie Hammer’s audiobook of “Call Me”?

ACIMAN: Yes, of course and I loved it. It took me a bit to get used to the fact that Oliver is actually reading Elio’s story. It was off putting for the first few minutes but then you get used to it and it’s fine.

BLADE: Luca has been talking about a sequel. How involved are you in that and what is your general feeling? Outside of “The Godfather,” sequels usually end up being mistakes.

ACIMAN: Well you said something very true. It could easily become like “Rocky 5, 6, 7, 8,” which are terrible movies, although I do love “Rocky IV” I have to admit, I don’t know why. But anyway no, we have had conversations about the sequel but I think we’re still a few years away from it because the actors would have to be a bit older so we can see how time might affect them. The story is going to have to take a new spin and adapt some of the stuff at the end of the book which was left off in the film but it’s up in the air. It’s a nice idea but we have no idea where we’re going with it yet.

BLADE: So it’s very preliminary?

ACIMAN: Totally.

BLADE: Did this idea come up during production or after the movie was a hit?

ACIMAN: No, during production. When I met Luca in Italy, he was already talking about a sequel.

BLADE: Do you think that influenced his decision on how to end the movie?

ACIMAN: I don’t know. It’s not the cliffhanger you have at the end of a season on television for example. It’s more a quiet closure that could easily be reopened again if we decide to.

BLADE: Where did you watch the Oscars and how did you feel when James Ivory won?

ACIMAN: I was there, seated a bit back. They didn’t say “Call Me By Your Name” when he won so for a split second I was thinking, “Oh, we lost,” and I turned to my wife and she said, “We won, you idiot.” I was very happy and particularly touched by the graciousness that he gave me a call out. … It made me feel that I too, got an Oscar through him.

BLADE: Ivory said he would have liked more nudity in the film. It did feel a bit incongruous to me that here we have this gay love story but there was more straight sex and nudity in it than gay. Not that you go for the sex but as a point of reference.

ACIMAN: I didn’t agree with him because he had male nudity, I think, in “A Room With a View” where you had three men running around the pond totally naked. When you see a woman nude, you see breasts and there’s nothing else really to see. You don’t see an open vulva to be sort of vulgar for a second. You don’t see that, genital nudity but you do with a man. … Frankly I don’t think it was necessary and I didn’t want to see them actually fucking. That would have been in bad interest to begin with. I don’t like to see the sexual act, gay or hetero, on screen. It really bores me. I no longer enjoy watching it. I mean if I want to see porn, I’ll go to a site and look at porn.

BLADE: Do you feel the film got shortchanged at the Oscars?

ACIMAN: I was frustrated. I thought to be honest, I haven’t seen the Churchill film (“Darkest Hour”) but I’ve seen cuts of it. I think there’s a bit of hysterical acting in it and I was very disappointed Timmy didn’t get it because I think he should have, age nonetheless. And I really felt the film itself should have gotten it because it’s a terrific film. Everybody is talking about it. … Even just two days ago, it was referenced in relation to the opera “Tristan and Isolde.” I thought it was a bad decision but one should never question the decision of judges, you know. So I left it at that but I was frustrated, of course I was.

Armie Hammer (left) as Oliver and Timothee Chalamet as Elio in ‘Call Me By Your Name.’ (Photo courtesy Sony Pictures Classics)

BLADE: Do you remember writing the scene where the title notion comes from and how that came to you?

ACIMAN: Yes. First of all, it was not the original title of the book. We went through a whole list of titles and at the very end I said, “What about ‘Call Me By Your Name?’” Now people ask me to sign the book to them using my name and they tell me they do that when they’re having sex. It becomes something very intimate when you give them your name. They become you whether it becomes for one second and then you forget about it and you’re embarrassed or you do it repeatedly. In the film, it was a gesture where you absolutely want to be one with someone and you basically no longer know where their body starts and yours is. That confusion is one of the most beautiful things in life I think.

BLADE: I took it as sort of a gay reclaiming of the biblical notion of “the two shall become one.”

ACIMAN: Could be.

BLADE: In the book, they kiss after Elio vomits. They look in the toilet after each other. Were you saying that attraction sometimes is so intense it can transcend bodily functions we ordinarily would be repulsed by?

ACIMAN: Yeah, because I wanted basically aside from the fact that I wanted every orifice to be part of the game here, but it’s more than that. I think that body functions — many people, even married people will shut the door when they go to the bathroom. They don’t want the other person to see. Why? Because it’s disgusting? Or because it’s private? And the whole notion of the book is that there is no private. … If you ejaculate in a peach, I will eat the peach with your cum in it and I want to see you going to the bathroom. I want to know everything about you. … It’s an idyll to love so it has to include everything, even vomit.

BLADE: Some of the #MeToo stuff was same-sex like with James Levine and Kevin Spacey. I know that’s a whole other thing but the fact that that was playing out when the movie was so popular, did any of that land on your shores?

ACIMAN: No, not at all really. A, because I’m not really interested in it but what did land on my shore is the fact that Elio is 17 and Oliver is a grown up. … Many things happened to me at that age and I was just lucky to have found nicer people. … But I wanted Elio to be 17. … If he’d been 18, that would have seemed, to me at least, that I was trying to get the OK from the thought police.

BLADE: What are you writing now?

ACIMAN: I have a collection of essays tentatively called “Homo Irrealis,” that’s finished and I’m working on another book, sort of a bilateral novel about three lives … that explores how people have attractions to people of the opposite sex and the same sex.

BLADE: When did you discover Proust?

ACIMAN: When I was 14 the first time, then I stopped reading him because it was just too close. It was very, very close but I felt I wanted to be influenced by this guy but I still needed to read Dostoevsky so I put him off. But my father was a big Proustian lover and he had read Proust twice in his life. I discovered him again in my late teens and it changed my life, it changed me as a writer. It told me ironically that everything I had thought was OK and every way I wanted to write was OK since he was doing it.

BLADE: How much gets lost in translation with Proust?

ACIMAN: Well some of it is definitely lost but if you’re dealing with a very good translator, the loss is not severe.

BLADE: When you’re writing, do your productive daydreams very often seep over into procrastination?

ACIMAN: Are you kidding, I’m the most undisciplined writer in the world. I re-write many, many, many times so that’s why I don’t produce a giant blockbuster every two years as many writers do.

BLADE: Was the three-and-a-half months for “Call Me” revisions and everything?

ACIMAN: Yes. I began it in April and handed in the manuscript on Labor Day in 2005.

BLADE: Do you enjoy teaching or just do it to pay the bills?

ACIMAN: No, I need teaching because it turns out, I’ll say this quite openly, I think I’m a very good teacher because I take people to places that they ordinarily would never have thought existed. And I like to hear people think and hear them draw on their feelings to what they’re thinking about as opposed to just giving me the gibberish jargon they think they need to. … If I just did it to pay the bills, I would have stopped.

a&e features

Visit Cambridge, a ‘beautiful secret’ on Maryland’s Eastern Shore

New organization promotes town’s welcoming vibe, LGBTQ inclusion

CAMBRIDGE, Md. — Driving through this scenic, historic town on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, you’ll be charmed by streets lined with unique shops, restaurants, and beautifully restored Victorian homes. You’ll also be struck by the number of LGBTQ Pride flags flying throughout the town.

The flags are a reassuring signal that everyone is welcome here, despite the town’s location in ruby red Dorchester County, which voted for Donald Trump over Kamala Harris by a lopsided margin. But don’t let that deter you from visiting. A new organization, Proudly Cambridge, is holding its debut Pride event this weekend, touting the town’s welcoming, inclusive culture.

“We stumbled on a beautiful secret and we wanted to help get the word out,” said James Lumalcuri of the effort to create Proudly Cambridge.

The organization celebrates diversity, enhances public spaces, and seeks to uplift all that Cambridge has to share, according to its mission statement, under the tagline “You Belong Here.”

The group has so far held informal movie nights and a picnic and garden party; the launch party is June 28 at the Cambridge Yacht Club, which will feature a Pride celebration and tea dance. The event’s 75 tickets sold out quickly and proceeds benefit DoCo Pride.

“Tickets went faster than we imagined and we’re bummed we can’t welcome everyone who wanted to come,” Lumalcuri said, adding that organizers plan to make “Cheers on the Choptank” an annual event with added capacity next year.

One of the group’s first projects was to distribute free Pride flags to anyone who requested one and the result is a visually striking display of a large number of flags flying all over town. Up next: Proudly Cambridge plans to roll out a program offering affirming businesses rainbow crab stickers to show their inclusiveness and LGBTQ support. The group also wants to engage with potential visitors and homebuyers.

“We want to spread the word outside of Cambridge — in D.C. and Baltimore — who don’t know about Cambridge,” Lumalcuri said. “We want them to come and know we are a safe haven. You can exist here and feel comfortable and supported by neighbors in a way that we didn’t anticipate when we moved here.”

Lumalcuri, 53, a federal government employee, and his husband, Lou Cardenas, 62, a Realtor, purchased a Victorian house in Cambridge in 2021 and embarked on an extensive renovation. The couple also owns a home in Adams Morgan in D.C.

“We saw the opportunity here and wanted to share it with others,” Cardenas said. “There’s lots of housing inventory in the $300-400,000 range … we’re not here to gentrify people out of town because a lot of these homes are just empty and need to be fixed up and we’re happy to be a part of that.”

Lumalcuri was talking with friends one Sunday last year at the gazebo (affectionately known as the “gayzebo” by locals) at the Yacht Club and the idea for Proudly Cambridge was born. The founding board members are Lumalcuri, Corey van Vlymen, Brian Orjuela, Lauren Mross, and Caleb Holland. The group is currently working toward forming a 501(c)3.

“We need visibility and support for those who need it,” Mross said. “We started making lists of what we wanted to do and the five of us ran with it. We started meeting weekly and solidified what we wanted to do.”

Mross, 50, a brand strategist and web designer, moved to Cambridge from Atlanta with her wife three years ago. They knew they wanted to be near the water and farther north and began researching their options when they discovered Cambridge.

“I had not heard of Cambridge but the location seemed perfect,” she said. “I pointed on a map and said this is where we’re going to move.”

The couple packed up, bought a camper trailer and parked it in different campsites but kept coming back to Cambridge.

“I didn’t know how right it was until we moved here,” she said. “It’s the most welcoming place … there’s an energy vortex here – how did so many cool, progressive people end up in one place?”

Corey van Vlymen and his husband live in D.C. and were looking for a second home. They considered Lost River, W.Va., but decided they preferred to be on the water.

“We looked at a map on both sides of the bay and came to Cambridge on a Saturday and bought a house that day,” said van Vlymen, 39, a senior scientist at Booz Allen Hamilton. They’ve owned in Cambridge for two years.

They were drawn to Cambridge due to its location on the water, the affordable housing inventory, and its proximity to D.C.; it’s about an hour and 20 minutes away.

Now, through the work of Proudly Cambridge, they hope to highlight the town’s many attributes to residents and visitors alike.

“Something we all agree on is there’s a perception problem for Cambridge and a lack of awareness,” van Vlymen said. “If you tell someone you’re going to Cambridge, chances are they think, ‘England or Massachusetts?’”

He cited the affordability and the opportunity to save older, historic homes as a big draw for buyers.

“It’s all about celebrating all the things that make Cambridge great,” Mross added. “Our monthly social events are joyful and celebratory.” A recent game night drew about 70 people.

She noted that the goal is not to gentrify the town and push longtime residents out, but to uplift all the people who are already there while welcoming new visitors and future residents.

They also noted that Proudly Cambridge does not seek to supplant existing Pride-focused organizations. Dorchester County Pride organizes countywide Pride events and Delmarva Pride was held in nearby Easton two weeks ago.

“We celebrate all diversity but are gay powered and gay led,” Mross noted.

To learn more about Proudly Cambridge, visit the group on Facebook and Instagram.

What to see and do

Cambridge, located 13 miles up the Choptank River from the Chesapeake Bay, has a population of roughly 15,000. It was settled in 1684 and named for the English university town in 1686. It is home to the Harriet Tubman Museum, mural, and monument. Its proximity to the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge makes it a popular stop for birders, drawn to more than 27,000 acres of marshland dubbed “the Everglades of the north.”

The refuge is walkable, bikeable, and driveable, making it an accessible attraction for all. There are kayaking and biking tours through Blackwater Adventures (blackwateradventuresmd.com).

Back in town, take a stroll along the water and through historic downtown and admire the architecture. Take in the striking Harriet Tubman mural (424 Race St.). Shop in the many local boutiques, and don’t miss the gay-owned Shorelife Home and Gifts (421 Race St.), filled with stylish coastal décor items.

Stop for breakfast or lunch at Black Water Bakery (429 Race St.), which offers a full compliment of coffee drinks along with a build-your-own mimosa bar and a full menu of creative cocktails.

The Cambridge Yacht Club (1 Mill St.) is always bustling but you need to be a member to get in. Snapper’s on the water is temporarily closed for renovations. RaR Brewing (rarbrewing.com) is popular for craft beers served in an 80-year-old former pool hall and bowling alley. The menu offers burgers, wings, and other bar fare.

For dinner or wine, don’t miss the fantastic Vintage 414 (414 Race St.), which offers lunch, dinner, wine tasting events, specialty foods, and a large selection of wines. The homemade cheddar crackers, inventive flatbreads, and creative desserts (citrus olive oil cake, carrot cake trifle) were a hit on a recent visit.

Also nearby is Ava’s (305 High St.), a regional chain offering outstanding Italian dishes, pizzas, and more.

For something off the beaten path, visit Emily’s Produce (22143 Church Creek Rd.) for its nursery, produce, and prepared meals.

“Ten minutes into the sticks there’s a place called Emily’s Produce, where you can pay $5 and walk through a field and pick sunflowers, blueberries, you can feed the goats … and they have great food,” van Vlymen said.

As for accommodations, there’s the Hyatt Regency Chesapeake Bay (100 Heron Blvd. at Route 50), a resort complex with golf course, spa, and marina. Otherwise, check out Airbnb and VRBO for short-term rentals closer to downtown.

Its proximity to D.C. and Baltimore makes Cambridge an ideal weekend getaway. The large LGBTQ population is welcoming and they are happy to talk up their town and show you around.

“There’s a closeness among the neighbors that I wasn’t feeling in D.C.,” Lumalcuri said. “We look after each other.”

a&e features

James Baldwin bio shows how much of his life is revealed in his work

‘A Love Story’ is first major book on acclaimed author’s life in 30 years

‘Baldwin: A Love Story’

By Nicholas Boggs

c.2025, FSG

$35/704 pages

“Baldwin: A Love Story” is a sympathetic biography, the first major one in 30 years, of acclaimed Black gay writer James Baldwin. Drawing on Baldwin’s fiction, essays, and letters, Nicolas Boggs, a white writer who rediscovered and co-edited a new edition of a long-lost Baldwin book, explores Baldwin’s life and work through focusing on his lovers, mentors, and inspirations.

The book begins with a quick look at Baldwin’s childhood in Harlem, and his difficult relationship with his religious, angry stepfather. Baldwin’s experience with Orilla Miller, a white teacher who encouraged the boy’s writing and took him to plays and movies, even against his father’s wishes, helped shape his life and tempered his feelings toward white people. When Baldwin later joined a church and became a child preacher, though, he felt conflicted between academic success and religious demands, even denouncing Miller at one point. In a fascinating late essay, Baldwin also described his teenage sexual relationship with a mobster, who showed him off in public.

Baldwin’s romantic life was complicated, as he preferred men who were not outwardly gay. Indeed, many would marry women and have children while also involved with Baldwin. Still, they would often remain friends and enabled Baldwin’s work. Lucien Happersberger, who met Baldwin while both were living in Paris, sent him to a Swiss village, where he wrote his first novel, “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” as well as an essay, “Stranger in the Village,” about the oddness of being the first Black person many villagers had ever seen. Baldwin met Turkish actor Engin Cezzar in New York at the Actors’ Studio; Baldwin later spent time in Istanbul with Cezzar and his wife, finishing “Another Country” and directing a controversial play about Turkish prisoners that depicted sexuality and gender.

Baldwin collaborated with French artist Yoran Cazac on a children’s book, which later vanished. Boggs writes of his excitement about coming across this book while a student at Yale and how he later interviewed Cazac and his wife while also republishing the book. Baldwin also had many tumultuous sexual relationships with young men whom he tried to mentor and shape, most of which led to drama and despair.

The book carefully examines Baldwin’s development as a writer. “Go Tell It on the Mountain” draws heavily on his early life, giving subtle signs of the main character John’s sexuality, while “Giovanni’s Room” bravely and openly shows a homosexual relationship, highly controversial at the time. “If Beale Street Could Talk” features a woman as its main character and narrator, the first time Baldwin wrote fully through a woman’s perspective. His essays feel deeply personal, even if they do not reveal everything; Lucian is the unnamed visiting friend in one who the police briefly detained along with Baldwin. He found New York too distracting to write, spending his time there with friends and family or on business. He was close friends with modernist painter Beauford Delaney, also gay, who helped Baldwin see that a Black man could thrive as an artist. Delaney would later move to France, staying near Baldwin’s home.

An epilogue has Boggs writing about encountering Baldwin’s work as one of the few white students in a majority-Black school. It helpfully reminds us that Baldwin connects to all who feel different, no matter their race, sexuality, gender, or class. A well-written, easy-flowing biography, with many excerpts from Baldwin’s writing, it shows how much of his life is revealed in his work. Let’s hope it encourages reading the work, either again or for the first time.

a&e features

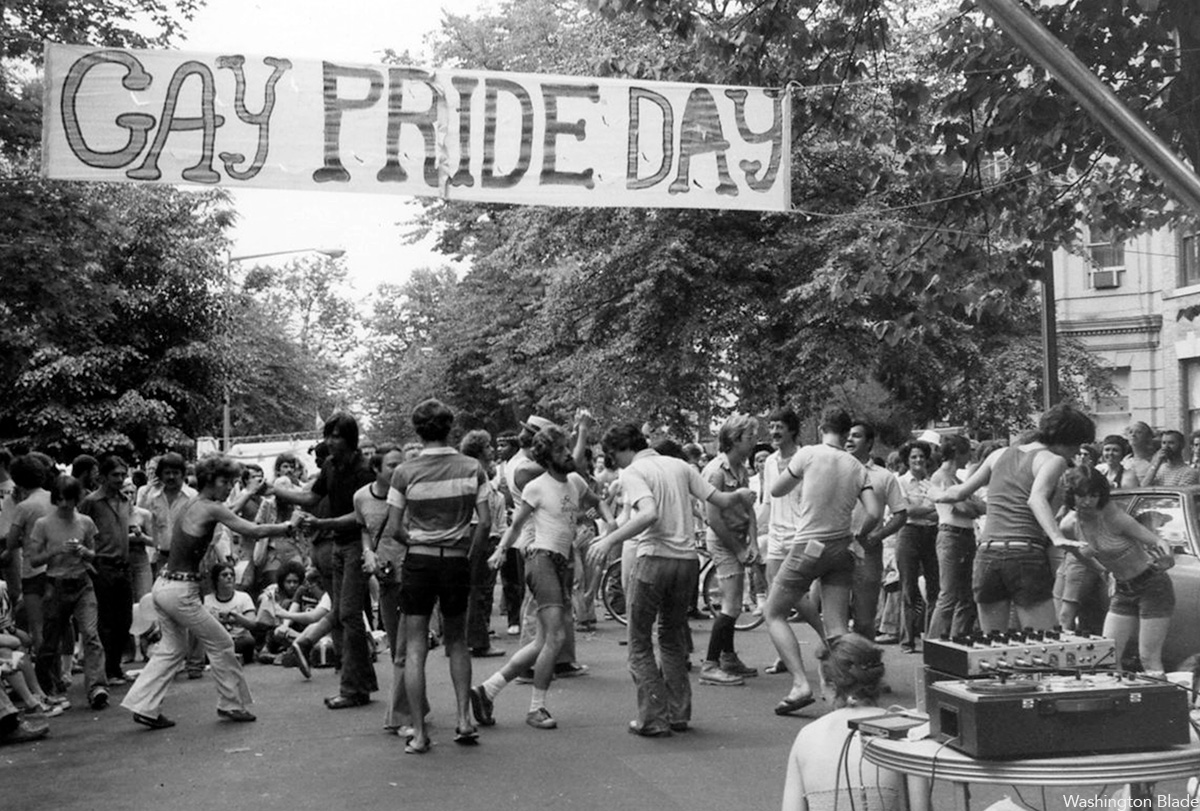

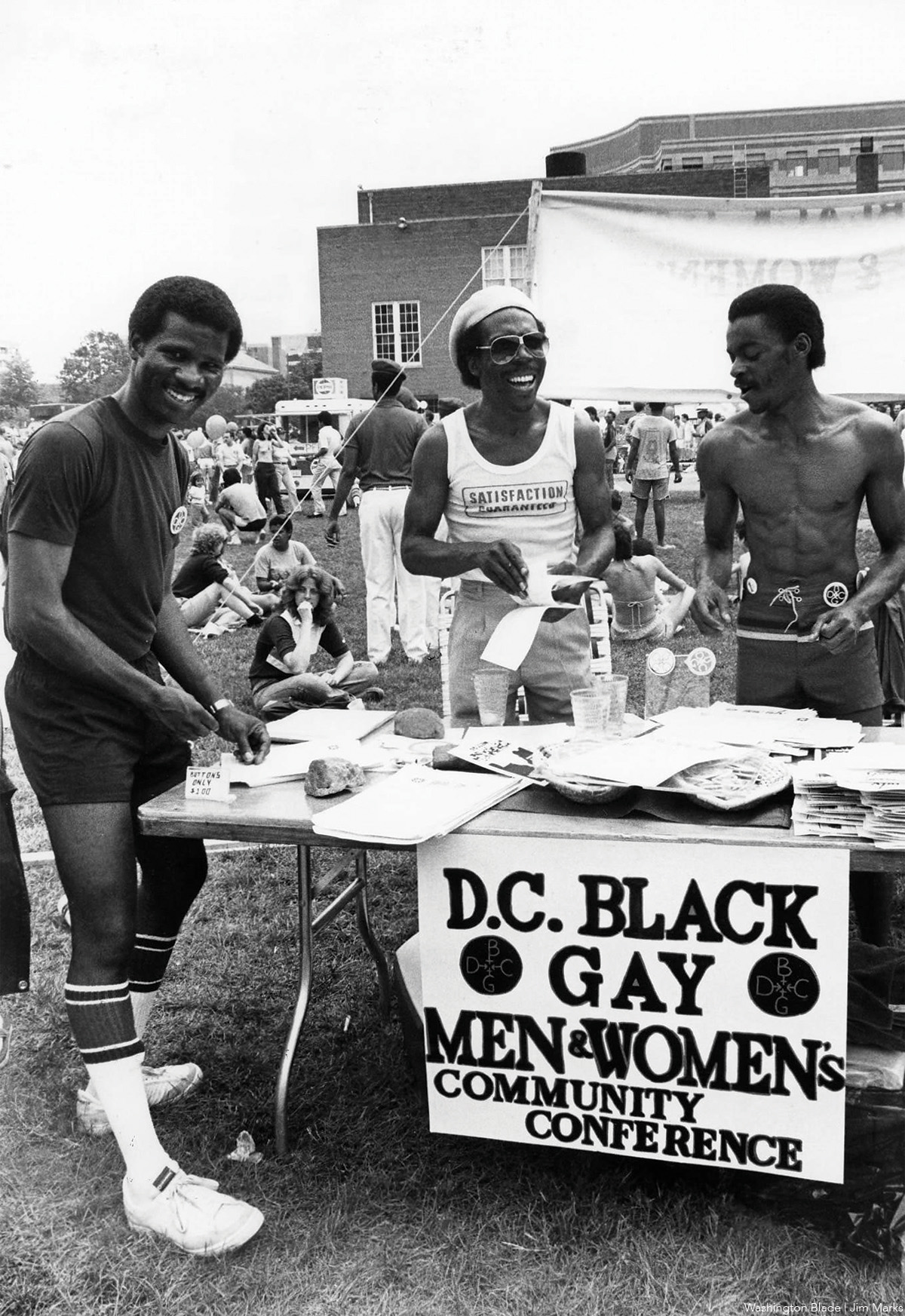

Looking back at 50 years of Pride in D.C

Washington Blade’s unique archives chronicle highs, lows of our movement

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of LGBTQ Pride in Washington, D.C., the Washington Blade team combed our archives and put together a glossy magazine showcasing five decades of celebrations in the city. Below is a sampling of images from the magazine but be sure to find a print copy starting this week.

The magazine is being distributed now and is complimentary. You can find copies at LGBTQ bars and restaurants across the city. Or visit the Blade booth at the Pride festival on June 7 and 8 where we will distribute copies.

Thank you to our advertisers and sponsors, whose support has enabled us to distribute the magazine free of charge. And thanks to our dedicated team at the Blade, especially Photo Editor Michael Key, who spent many hours searching the archives for the best images, many of which are unique to the Blade and cannot be found elsewhere. And thanks to our dynamic production team of Meaghan Juba, who designed the magazine, and Phil Rockstroh who managed the process. Stephen Rutgers and Brian Pitts handled sales and marketing and staff writers Lou Chibbaro Jr., Christopher Kane, Michael K. Lavers, Joe Reberkenny along with freelancer and former Blade staffer Joey DiGuglielmo wrote the essays.

The magazine represents more than 50 years of hard work by countless reporters, editors, advertising sales reps, photographers, and other media professionals who have brought you the Washington Blade since 1969.

We hope you enjoy the magazine and keep it as a reminder of all the many ups and downs our local LGBTQ community has experienced over the past 50 years.

I hope you will consider supporting our vital mission by becoming a Blade member today. At a time when reliable, accurate LGBTQ news is more essential than ever, your contribution helps make it possible. With a monthly gift starting at just $7, you’ll ensure that the Blade remains a trusted, free resource for the community — now and for years to come. Click here to help fund LGBTQ journalism.

-

U.S. Supreme Court5 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court5 days agoSupreme Court upholds ACA rule that makes PrEP, other preventative care free

-

U.S. Supreme Court5 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court5 days agoSupreme Court rules parents must have option to opt children out of LGBTQ-specific lessons

-

Television5 days ago

Television5 days ago‘White Lotus,’ ‘Severance,’ ‘Andor’ lead Dorian TV Awards noms

-

Music & Concerts5 days ago

Music & Concerts5 days agoBerkshire Choral to commemorate Matthew Shepard’s life