National

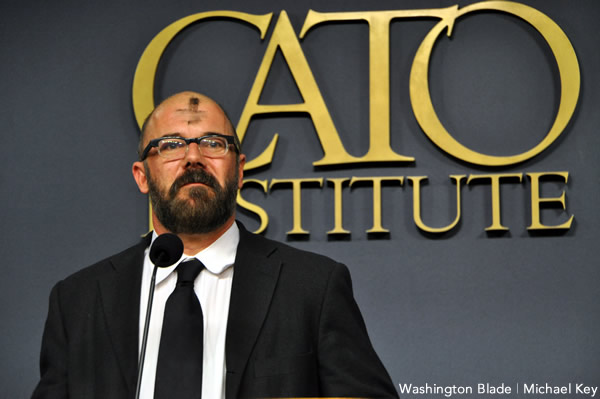

Andrew Sullivan doesn’t care what you think

Gay commentator talks new book, state of LGBTQ movement

Andrew Sullivan, the gay conservative commentator known for his early advocacy of same-sex marriage and, more recently, for being a Trump critic, talked to the Washington Blade upon publication of his new book, “Out on a Limb.”

Among the wide-ranging topics he addressed: the AIDS movement’s place in the larger LGBTQ movement; the role of the LGBTQ community in cancel culture; the future for gay men in Afghanistan; and gay men’s attention to fitness and the new role for gyms.

The full interview, which took place by phone on Sept. 13, follows:

Washington Blade: “Out on a Limb” is a collection of your writings, from the past 30 years. Can you tell me a little bit about what the process was for selecting which of those writings should go in this book, and in looking back at them if anything jumped out at you?

Andrew Sullivan: Oh, it was a nightmare process because I’ve written ridiculous amounts of words over the 32 years. And I couldn’t have done it without help from interns and friends, and especially my colleague Chris Bodenner, who trolled through a lot. And I don’t like reading my own pieces after they’ve been published. I don’t know I have a writer’s allergy to it. So I have to say it was kind of agonizing to go through everything all over again. And then last summer I just went through with a couple of other people just try to get some objective take on it because you’re far too close to make it your own, so it took a long time to sort out which was which, and we had to throw out a lot. But in the end I tried to make it so that there are pieces from almost every single year, so it spans, evenly the period that has a multiplicity of topics. And the ones that I think I’m sort of proudest of or that help portray exactly where I’m coming from.

And one of the frustrations of living in the Twitter world is that you can get defined by one sentence you wrote, 25 years ago, and they just hammer that on you and it’s hard for you to show that your work is actually different than that. You’re not the caricature. And so, One way to do that is just simply publish your work and have people look at it and make up their own minds.

Blade: Right. Well, looking at the book and looking at some of the early essays — I mean I’m an avid reader of your column in recent years, but some of the stuff is written before that when I was much younger. One that really jumped out at me was the prevalence of the AIDS epidemic, and its impact on the gay community in the the height of the epidemic in the in the 80s in the in the early 90s. I’d like to ask you to kind of bring that to the present, like, how do you think our approach to the coronavirus compares to our approach to HIV/AIDS back then?

Sullivan: I think one of the things you notice is that there are many similar themes in all sorts of different plagues through history. There’s denial that it’s happening, there are crackpot theories about what’s going on. It tends to divide people who have the virus from people who don’t have the virus. It creates a sense of anxiety, obviously. In all those things, it’s quite similar and often the government bureaucracy is also lumbering. It’s also true that in this case, as with HIV in the end, it was the pharmaceutical companies that gave us the real breakthroughs to actually manage it.

So, more similar in many ways than you might think, but obviously, the differences are huge too and as much as HIV was concentrated so much in a small and separate — in some ways — community and its fatality rate was for a long time, not point-one percent, but 100 percent. It killed everyone, and also it was so selective in its killing that other people could avoid it, or not even notice it or have it be going on around them without even seeing it. And so obviously, it was — for my generation — it was a defining event, quite obviously and I think it’s immeshment with the rebirth of the gay rights movement in the 1990s is absolutely part of the story. I really don’t believe that you could tell the story of gay civil rights in the 90s and 2000s without telling the story of AIDS. I don’t think it would have happened the same way or even at all without that epidemic.

And you know, those early pieces written about in New York and Washington in the 1990s or thereafter are pretty brutal. I mean, I tried to convey what it really was like. I mean, one thing I try and tell kids today is that, imagine the current Blade, which is not as thick or as big as the old Blade, but the Blade you had would be just about enough to contain the weekly obits that used to run each week. And I don’t think those who didn’t live through that will ever understand that. But I hope maybe, with some of the essays in this book, they’ll see a little bit more about what we went through and how we managed to construct arguments for equality in the middle of really staggering loss and pain and fear.

Blade: And yeah, I’ve looked through some of our archival material and definitely the obituaries were a key component if not almost the center of the Washington Blade throughout the AIDS epidemic.

Sullivan: They were. And you know because we were much a closer community then, because this was before apps, this was before social acceptance. We tended to know everyone, because we met and socialized in the bars and clubs and in the gyms and the parks, and so it was terrifying how many of the faces that you saw in those obits you knew, even if you didn’t know them as friends, as many of us did, you knew them as faces in the bar, and to watch them all be struck down in such numbers was obviously a formative event for all of us, those of us who were, where I am, which is I’m late 50s now, we really experienced something unique. Many of the people we experienced it with are gone. And I think there’s often a sense of incomprehension that the younger generation really doesn’t understand what happened, and worse, really doesn’t care.

Blade: Really doesn’t care? I mean, that’s a very strong statement. What are you basing that on?

Sullivan: The lack of any discussion of it, any memory of it, anyone under the age of 30 ever asking me, or anyone who lived through it, what it was like. I mean, you tell me where the memory of it is held. Am I missing something?

Blade: The memory, if you’re speaking of just public discussion, even within the gay community, I think it is very faded.

Sullivan: It’s almost as if it didn’t happen. This is quite common, you know, with plagues, too. Like the 1918 plague was disappeared in the memory hole, very quickly.

But this was such a traumatizing event for so many of us. Now, the truth is, most other communities have children, and they tell their children and that’s how the memories — for example the Holocaust or even the Vietnam War and other things — are perpetuated. We have no — by and large we don’t have kids and we don’t tell them those stories. And so each generation is afresh and they do see it as something that happened. I don’t think they’re not aware of it, but it’s certainly not something that’s a particular interest, I think, to most young gay men.

Blade: It’s certainly very sobering to read those essays in the book that depict what’s going on at the height of the AIDS epidemic at that time.

Sullivan: I obviously tried to air some internal laundry, as it were. I tried to talk about things that other people didn’t want to talk about, and of course that got me into trouble. But I think the essays stand up.

Blade: I feel almost awkward asking you this next question because it has very much to do with talking about the present of what’s happening in the in the gay rights movement, but you did bring up civil rights — how that animated the gay movement in the 90s in the early days, and now the situation with the Human Rights Campaign president being terminated after being ensnared in the report on the Cuomo affair, and a public dispute with the board. I want to ask you how representative do you think that situation is of the LGBTQ movement?

Sullivan: Well I would say this: I do think it’s simply a fact that the core civil rights ambitions of all of us have been realized. It’s almost entirely done. These groups are desperately searching for things to do. But since gay people and transgender people are now protected under the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which is as a strong a protection as you can get, and since we can marry one another anywhere in the country and since we can serve our country in the military, they’ve really not got much left. So of course, they start entering into different areas like the issue of race, or the issue of gender or sexual harassment. And this is just a desperate attempt to stay relevant in some way. There’s no reason for them, I don’t think, to really function the way they functioned before. The movement is done, and I think a lot of people understand that, which is why maybe one of the underlying reasons why Mr. David disappeared is because membership income has plummeted, as I understand it.

And also, I think this is a sense in which the current mainstream — what I would call the alphabet movement people, the LGBTQRSTVWXYZ people — they don’t represent most gay men and women, and lesbians or even, I don’t think, a lot of trans people. And I think it’s certainly not a gay rights movement at this point. I think gay men are a complete afterthought. So, I just think it’s a function of — it’s the price of success is catastrophic success. Let’s put it that way. And you know, once you’ve achieved your things, you should shut down and move on. And they have to keep inventing and creating new senses of crisis of massive discrimination or huge waves of alleged trans genocide resources. This is all completely fanciful, and not related to actual reality, and those of us who actually went through some serious shit can see what is unserious about this.

Blade: I think a lot of our readers are probably going to point out these transgender women are being forced into these dangerous situations to make a living and because of that they are suffering violence.

Sullivan: Yes. That is true and awful, obviously. But is it an epidemic? No. Is the murder rate higher for that group and other groups in society? So far as we can analyze that, no.

I don’t know what the solution is to the other thing, and how do we help trans people not be forced into those horribly dangerous situations. That’s what we should definitely consider — how we as a community could help avoid that. But I don’t see what an organization is going to do about it except raise money off it.

Blade: What if we’ve experienced catastrophic success as you say in the moment, I was going ask you what qualities we should be looking for in the next Human Rights Campaign president, but maybe —

Sullivan: I don’t think there should be one. I think somebody will wind it down is what I would hope for. I know that’s going to get people nuts, going to send people nuts, but no, what are their goals now, what are they really fighting for? What measures do they want us to pass? That’s what I want to know, except for this Equality Act, which most of which has already been done. I mean, we were told in the 80s that they wanted to have this ENDA. I mean, it’s been going on forever. And we were told in the 90s we should put off marriage equality. Remember, HRC was against it for the first 10 years on the grounds it would upset the Democrats and the Clintons. We should wait, because only the employment discrimination issue really matters, and here we are 30 years later and they’re still pushing the same bill except it doesn’t have anything else in it because most of it’s already been done by the Supreme Court. So, it has to turn itself into an organization that’s supporting, for example, a group like Black trans people, and again, the question is, what does that mean, supporting them? What does it mean? I don’t know what it means, except their ability to raise money.

Blade: That kind of brings me to the next question: I know you’ve said many times that the gay rights movement is over, but what about the —

Sullivan: It’s not over as such, I mean obviously we have to be vigilant about the gains we’ve made and we have to be clear that we rebut lies. There’s still work to be done within our own community to each other. So I don’t mean that’s over, but the idea that we are trying to advance core civil rights, we have got them. You’ve got to learn to take “yes” for an answer.

Blade: The question I want to pose, if that is the case that we have our core civil rights, what about the gay press? Do you think there’s still a role for the gay press or are you just simply humoring me by doing this interview?

Sullivan: No, obviously. There’s press for almost every community in the world, and so absolutely, yes. There are issues that come up, all sorts of questions that we have to discuss from our businesses, to our clubs, to our bars to our culture. I mean, for example, we need coverage of the meth epidemic that is, in my view by far, the biggest crisis facing gay men right now, and which you almost never hear discussed in the gay press or in the gay rights organizations. And yet, that is, I fear, a huge crisis for us, killing God knows how many men. And the gay press has a role in bringing that to light, and opening a discussion of that and helping us find solutions to that. So, there always will be a need for a gay press.

Blade: And in some ways, for the gay press I would say that that makes things, there’s advantages and disadvantages to that. Advantages in that it’s a well-defined niche and disadvantages in the fact that it has to compete more with mainstream publications.

Sullivan: Yes. You didn’t use to. I mean, you used to be the only place to get any bloody news about the gay community, now you can’t get through the pages of the New York Times without being told something new about some part of our world, excessively so I might think. Come on, it gets kind of crazy at times.

Blade: Is there an example of something you think was crazy that you saw recently?

Sullivan: Well I think you know the way the New York Times covered Pride for weeks on end. I mean, at some point, you’re just like enough already.

Blade: I want to talk about Afghanistan, I was reading one of your recent columns before you went on vacation, about the rightness of that war finally coming to an end because it was — I think you call it the most pointless war that America has ever fought. That’s not the exact quote, but something along those lines. And in that column, you do acknowledge there are situations that this withdrawal has had an impact on. You go through a list, and one of them is gay men who would be executed in Afghanistan under Taliban rule. So, if you welcome this withdrawal, what about the consequences for a gay man in Afghanistan?

Sullivan: It’s horrifying. And in my view, we should be doing better at focusing on the gay people who are truly oppressed in the world, and they’re in brutal regimes, often with no political rights, not just in Eastern Europe, Poland, the Middle East and Africa. These are people gay people who are really, really up against the wall in many places. And I think we need to be very aggressive in helping many of them who are really beleaguered get asylum. I was on the board of Immigration Equality for quite a long time. And I’m very proud of the work Immigration Equality does on the asylum question, but I think we’ve learned we can’t occupy half the world to try and defend gay rights. It’s a wildly impractical move. We can highlight their plight, we can help some escape, but we can’t occupy the world and make it better for gay people, I’m afraid.

We have made enormous progress, but you only have to think about what’s happening in Poland or Hungary, or the Muslim world, or Afghanistan or Iran or even places obviously in Africa to to see we have a huge amount of work to do, and I wish you would focus on them now and be a beacon for them and to help them but I don’t think you do that by force of arms. … There are limits to what we can do and there were terrible consequences for overreaching those limits.

Blade: You said there is work to be done to help these people and you mentioned asylum as being one option, but is that all there is? What will this work look like?

Sullivan: Well I think we can help fund groups and organizations. I think people in this country will be happy to help, I certainly think it would be worth helping more than it would be sending money to the Human Rights Campaign. So, yes, I think I mean different ways you can — you can support Immigration Equality, for example, which does the legal work for asylum cases. Incredibly important. Wins almost every single one. Reach out to people who are in those places and communicate with them and support them. There are groups that help with money and help with just morale.

Blade: Speaking more generally about the concept of American intervention overseas to advance democracy, you’ve gone through a transformation on your view. You’ve talked quite a bit about your regret for supporting for the Iraq war. Was there a pivotal moment for you when you changed your view on this, or was it something that was more of a gradual evolution?

Sullivan: It wasn’t that gradual because the evidence of the failure of the war was almost immediate. So it did happen quite quickly, but for me, obviously the emergence that we were torturing prisoners was a complete deal breaker for me that many of us supported foolishly but with good intentions, we wanted to prevent and stop this murderous monster, Saddam, from torturing and killing people. And when we tried to remove him, ended up torturing people, you have a classic irony, and one that we have to repudiate …

One of the things that I do, when I think about the gay stuff is that — I don’t want to toot my own horn — but in the 90s, there was a handful of us supporting marriage equality. And these pieces in the book are the key building blocks of the argument in the 90s, and I think there is something of value in the history of seeing how we crafted those arguments, how we made a liberal argument, how we brought in conservatives, how we talked openly and debated openly with our opponents.

I mean, I did an anthology that included all the views against marriage equality. I did my own pieces but I also published Maggie Gallagher and Bill Bennett, for example. And I think that’s, that’s a part of the history that has been missed.

The 90s were the time when we formulated, honed, finessed the arguments, despite opposition from the gay rights establishment. I think we crafted successful arguments that went on to win. And that’s a really crucial thing, and there was only a handful of us that was doing that at the time. And so, I’m really proud of that legacy in this book. These are the arguments that help give us marriage equality, and it required reframing the gay rights movement around the question of our humanity, our common ground with straight people with formal legal equality, and has absolutely nothing to do with wokeness, or with attacking people for being bigots, or all the anger energy that is today aimed at demonizing your opponents. We attempted to persuade our opponents, not demonize them.

Blade: That wonderfully brings me to my next question because I was going to ask you, with the marriage victory six years ago now — in essence was that a restructuring of marriage, an institution that has been around for as long as almost probably humanity has been around. I’m just wondering if the restructuring of that institution played a role in contributing to the emergence of woke ideology that we’re seeing now.

Sullivan: I don’t think so. Most of the people that are now in the throes of woke ideology really were not interested in marriage equality and were completely absent in the campaign. They were also absent in the campaign for military service, because the people running the gay rights movement today, didn’t like marriage as an institution. They wanted to end it, and they opposed the military as a militaristic and an enemy institution, just as today’s extremists also oppose gay cops. So I don’t think that. I do think, however, that having won core ramparts for our civil rights, they had to find something else to do and screaming at straight people, and at cis people seems to be the new mode. I don’t think it helps anyone the way this campaign is currently being conducted nothing some of the extremist elements in trans ideology, are setting back the image and rights and dignity of gay people and trans people for that matter.

Blade: ‘Woke ideology’ is also very closely associated with the emergence of cancel culture. If you think, not too long ago, being gay would get you cancelled though it was not, the concept wasn’t exactly those words. For example, I think Billie Jean King, when she was either outed and came out as lesbian, and as a tennis player, she lost all of her sponsorships. This is years ago. It was so shocking at the time. Is there a special role for the gay community in addressing cancel culture and to what degree do you think we’re fulfilling it or not, or even contributing to it?

Sullivan: I’ve lived it. I’ve been canceled by virtually every faction. I, my first book of marriage equality was picketed by the Lesbian Avengers, when I went to bookstores. Gay left activists tried to cancel me by publishing my personal ad, trying to accuse me of spreading AIDS, which was an unbelievable lie. I’ve had glasses thrown at me by gay rights activists, but I was also cancelled by the right when I stood up for us, and also oppose aspects of the war and of the Republican Party, and I’ve been one of the strongest critics of the Republican Party in this millennium that you can find. So I think if the alphabet people have their druthers, they would get me canceled today. They just can’t, because I’m now independent, and they can’t pressure advertisers or editors to fire people for the wrong views. But that some elements look to cancel people who help pioneer a lot of gay rights in the modern era strikes me as not exactly productive.

If you’re cancelled by the left or the right somewhat continuously, you only have to go back to your core supporters your core readers, and the general public, and that’s what Substack has enabled me to do, though it’s what also the original Daily Dish did. I’m not sure without those I would have been able to really keep up the fight in the 2000s for marriage equality, for example.

Blade: This animosity that you’ve experienced both on the right and the left, having glasses thrown at you, having your personal ad doxxed as it were — given your contributions to the gay rights movement, has that reaction surprised you?

Sullivan: No. Not really. I think that, look, divisions in arguments within the community are are healthy, not unhealthy. And I think, for reasons I didn’t choose, I became a very prominent gay person in the 90s, just by virtue of the fact that I was out from the get-go, first generation to be out from the get go, and when I became editor of the New Republic, I was the only openly gay journalist in the mainstream media in Washington or New York. I know that sounds insane, but it’s true. I was it. Who else were they going to talk to? And so, inevitably, I came, in ways that I never intended, to represent gay people but I never said that. I said that I only represent myself. I have no claim to represent anybody else, but that’s not the way the media works and I think people were enraged by that, and enraged when I said things that were not totally party-line. …

This is very common in minority communities where, you know, there’s a tall poppy syndrome where someone emerges and seeks to represent people, they have to be cut down pretty quickly. So part of that’s inevitable and certainly during the 90s and early 2000s, especially in the 90s dealing with AIDS, you can see why people were desperate and angry, and didn’t want any, any of the slightest internal debate. So I understand that. However, the cruelty of some of it. The viciousness of some of it. The real core homophobia, involved in it. I mean, how homophobic is it to find someone’s personal ad is blasted out to smear that person. That’s been done to gay men forever but it was done by gay activists against a gay man. There’s some deep ugliness out there, and it comes from frustration. It comes obviously from a sense of people’s own histories of being beleaguered and having their dignity removed. It comes from a sense of helplessness, comes from a sense of not having your own voice. So all that’s understandable. I just think people could have been a little less, and could still be, a little less personal and vicious about it toward other people.

Blade: I want to go back to marriage equality and win six years ago. Are there any consequences of that decision that you did not foresee?

Sullivan: I don’t think I foresaw that, once all these main achievements were won, that the gay rights movement would radicalize so quickly into something extremely left wing. That I didn’t fully anticipate. I thought the successes would probably help calm things down. We could move on to other issues we needed to resolve or need to be tackled. But essentially, I didn’t see the emergence of this hugely intolerant and ideologically extreme version of — it isn’t even gay rights anymore because this stuff is hostile, even for categories like homosexuality once you destroy categories all of sex, gender and sexual orientation, which means that gayness is on the chopping block for these people as well. They’re essentially in favor of dismantling our society. And I don’t think most gay men and lesbians actually want to dismantle our society. I think they want to make it better. I think they want to make it more humane. I think they want to make it more just. But I don’t think they want to dismantle the concept for example of biological sex. I don’t think they want to dismantle the concept of homosexuality, which is attraction to people of the same sex. And I think eventually gay people are going to wake up and realize this movement really is about the dismantling of homosexuality.

Blade: Building off of what you said about the tall poppy syndrome in the gay community, which you experienced, let’s look at that for a different community and that is Caitlyn Jenner within the transgender community in her run for governor. She’s arguably the most prominent transgender figure in recent months, even though many people in the transgender movement abhor that. Given what Caitlyn Jenner has done, do you think the transgender community owes a sort of thanks for bringing visibility to a different audience?

Sullivan: I think, you know, in the old days, our view was this: We always seek converts; we’re not seeking heretics. If you want more people to join you, you’re prepared to accept support from anywhere on your core issues. And if you do that, if you have open arms and a big tent and say, ‘Yeah. You agree with us on this, then we’re delighted to have you on our side.” That’s what did with marriage. Now, the people who want to be with you have to be subjected to these incredible ideological litmus tests. They have to be parsed and they have to be shredded, often, in their reputations.

Now, I’m not a supporter of Caitlyn Jenner. To be honest with you, I’m more of the “South Park” view of Caitlyn Jenner, but what the fuck? She is out there, she did help raise visibility for trans people. In the end, if you want to win and if you want to persuade people, you want as many different views representing you as possible, and so it’s a good thing if there are gay Republicans, a good thing that there are trans Republicans, a good thing that we can appeal to more people. We now have the majority of Republicans supporting marriage equality. When I started out that was unbelievable. So it’s — what I feel is that we’re stuck in a movement that’s really about finding enemies, destroying leaders and consumed with resentment and anger, and those kinds of movements are not only not very pretty, but they don’t often succeed.

Blade: And you see that being applied with Caitlyn Jenner in the transgender community?

Sullivan: Well, yeah. I think the minute you say something even slightly off accepted orthodox, they want you destroyed.

There are lots and lots of Americans who support trans rights if you are not convinced the biological sex doesn’t exist. There are compromises here.

Blade: I want to ask a couple of general questions. With what we’re seeing now, has Biden been living up to your expectations as president?

Sullivan: Pretty much, to be honest I wasn’t hugely — I was the “anyone but Trump” person. And I thought of the candidates, I thought Biden was the most plausible. I actually argued that he would be the best candidate a couple years ago. It’s in the book.

I think that’s all I’d say, except he’s turned out to be much more left in domestic policy than a lot of people — a lot of people realize, although I certainly expected it.

Blade: OK give me an example of that.

Sullivan: In enacting government-wide race and sex discrimination policies, making hiring and firing in the federal government, dependent upon your race and sex, sexual orientation or gender roles, as opposed to can you do that job or not?

Blade: I guess I don’t know the specific initiative. You’re talking about the executive order implementing Bostock?

Sullivan: The equity initiative across the — run by Susan Rice. With every government department, they have to make sure that they’re discriminating against certain race and sex in order to get the balance right.

Blade: What about Trump? Have you reevaluated anything about him since he left office?

Sullivan: I think my basic initial feeling about him remains, that he’s just out of his mind. There’s no way this person is a rational or credible person who belongs in human society. He’s a completely crazy person. And that’s fundamentally the problem, but he’s also a brilliant demagogue. I’m still worried about him.

Blade: What does that worry entail?

Sullivan: That he can come back and be president. That’s what I’m worried about. Obviously, it’s too soon to say, but the way in which he and increasingly his party treats the Constitution as if it is a game to be rigged as opposed to a set of rules we all agree to — really, really, unnerving deeply undemocratic, authoritarian impulse.

Blade: I also want to ask you — It might be uncomfortable, crossing boundaries here, but I’m just going to have at it because I’ve seen you at VIDA gym, quite a few times and it looks like you try to keep yourself in good physical shape. Is that something that you’ve always been attentive to, exercise? I’m just kind of curious because I think a lot of our readers are attentive to it too, so I’m just kind of wondering what if you could talk describe your experience with it.

Sullivan: Look, being gay — yeah, I think it’s part of — I’ve done weight training forever and ever and ever. And, you know, it’s good for you, especially as you get older. For me, it’s a way of taking my mind off everything else that’s in my head, and working out for an hour — I try to with a trainer — can be just mentally reviving, because it gets my mind off its usual patterns. I’ve been a bit of a bodybuilder in a way. It’s gone up and down, or whatever. It depends on — COVID was obviously a huge blow to it. Yeah, you know, it’s just how I live. It’s been like that forever, and the gym is also, I think become an important — with the collapse of gay bars, it’s become an important social institution more than it used to be, actually.

Blade: Do you mean in the way that it fosters a sense of networking and community?

Sullivan: Well, you know, it’s where you saw me, where you can, you know — the way that we used to more often in clubs and bars. … It is an important social institution as well as a fitness place. Sometimes VIDA U Street is incredibly intimidating, because there’s unbelievably huge and beautiful men there, and you always start finding yourself feeling puny in comparison.

Blade: Yeah, tell me about it.

Sullivan: That’s the arms race, you know, that’s men’s function of being a man more than being gay, I think. It’s just men are triggered by more superficial bodily attraction than women, and we are better able to — for good or ill — to dissociate the person from the body as it were. And so, where we’re competing with each other, you know, it’s a death race, really.

Blade: That was going to bring me to my next question because I was going ask you if you think gay men are paying too much attention to their physical bodies, to physical fitness.

Sullivan: I can’t judge anybody. I think it all depends on how you want to live your life and I don’t think it’s a problem as long as it’s healthy. I mean, it’s better than other things you could do with your life. But yes I think insofar as we have unbelievably exacting standards of physical beauty, and we punish people we don’t — or really isolate or marginalize people that don’t live up to them, you see groups of friends in the gay community — you see it here in Provincetown a lot — where it’s surprising how they all have the same level of handsomeness or beauty. There’s not a mix. I mean in the classic sense of beauty: big arms, big chest, you know, blah blah blah. And, that is, I think there’s a slight cruelty to some of that sometimes.

I think the bear world has helped a lot, as it were, soften that, literally, figuratively. You have a piece about bears in the book. But look, a beautiful man is a beautiful man. I mean there’s a reason you go to VIDA also because they’re fucking beautiful and extremely attractive, and no gay man should oppose that. It’s just that when we cross one another, sometimes we’re terribly cruel to each other.

Blade: Is that a function of being a man or a function of being gay?

Sullivan: It’s a function of being a man in a world where there are no women to check it because all the incentives are there. You’re just catering to your own — the thing about that is that we do it ourselves all the time. But yes, it does matter, in the gay world, if you’ve got a nice body, right?

And it’s not fair, yes. But it’s sometimes you just got to hack it. But then there’s always people out there who don’t like that, and we’re not used to that and plenty of life outside the gym, people have different ways of coming together, whether it be book clubs or just hanging out in the same bar or cafe, or the sports teams and so on and so forth. The range of gay life is so much larger than it used to be, which is so wonderful.

And that’s also in the book, too, the end of gay culture. I would say this: This book is really the story of someone in my generation, going from the 80s to today, the 2020s, the 80s to the 20s basically. We experienced something that no gay generation has ever experienced before or will ever experience again. We lived through the most exhilarating period of advances in gay dignity, rights and visibility. At the same time as we went through a viral catastrophe, and that combination of thrill and terror, you can hear it in the dance music at the time. This incredible high energy disco music with lyrics that would make you slit your wrists, with lyrics of great darkness and sadness. You hear it in Pet Shop Boys, particularly, Eurasia, all those synthpop energizing bands of the 80s and 90s.

Florida

Fla. House passes ‘Anti-Diversity’ bill

Measure could open door to overturning local LGBTQ rights protections

The Florida House of Representatives on March 10 voted 77-37 to approve an “Anti-Diversity in Local Government” bill that opponents have called an extreme and sweeping measure that, among other things, could overturn local LGBTQ rights protections.

The House vote came six days after the Florida Senate voted 25-11 to pass the same bill, opening the way to send it to Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, who supports the bill and has said he would sign it into law.

Equality Florida, a statewide LGBTQ advocacy organization that opposed the legislation, issued a statement saying the bill “would ban, repeal, and defund any local government programming, policy, or activity that provides ‘preferential treatment or special benefits’ or is designed or implemented with respect to race, color, sex, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or gender identity.”

The statement added that the bill would also threaten city and county officials with removal from office “for activities vaguely labeled as DEI,” with only limited exceptions.

“Written in broad and ambiguous language, the bill is the most extreme of its kind in the country, creating confusion and fear for local governments that recognize LGBTQ residents and other communities that contribute to strength and vibrancy of Florida cities,” the group said in a separate statement released on March 10.

The Miami Herald reports that state Sen. Clay Yarborough (R-Jacksonville), the lead sponsor of the bill in the Senate, said he added language to the bill that would allow the city of Orlando to continue to support the Pulse nightclub memorial, a site honoring 49 mostly LGBTQ people killed in the 2016 mass shooting at the LGBTQ nightclub.

But the Equality Florida statement expresses concern that the bill can be used to target LGBTQ programs and protections.

“Debate over the bill made expressly clear that LGBTQ people were a central target of the legislation,” the group’s statement says. “The public record, the bill sponsors’ own statements, and hours of legislative debate revealed the animus driving the effort to pressure local governments into pulling back from recognizing or resourcing programs targeting LGBTQ residents and other historically marginalized communities,” the statement says.

But the statement also notes that following outspoken requests by local officials, sponsors of the bill agreed to several amendments “ensuring local governments can continue to permit Pride festivals, even while navigating new restrictions on supporting or promoting them.”

The statement adds, “Florida’s LGBTQ community knows all too well how to fight back against unjust laws. Just as we did, following the passage of Florida’s notorious ‘Don’t Say Gay or Trans’ law, we will fight every step of the way to limit the impact of this legislation, including in the courts.”

The White House

Trump will refuse to sign voting bill without anti-trans provisions

Measure described as ‘Jim Crow 2.0’

President Donald Trump said he will refuse to sign any legislation into law unless Congress passes the “SAVE Act,” pressuring lawmakers to move forward with the controversial voting bill.

In posts on Truth Social and other social media platforms, the 47th president emphasized the importance of Republican lawmakers pushing the legislation through while also using the opportunity to denounce gender-affirming care.

“I, as President, will not sign other Bills until this is passed, AND NOT THE WATERED DOWN VERSION — GO FOR THE GOLD,” Trump posted. “MUST SHOW VOTER I.D. & PROOF OF CITIZENSHIP: NO MAIL-IN BALLOTS EXCEPT FOR MILITARY — ILLNESS, DISABILITY, TRAVEL: NO MEN IN WOMEN’S SPORTS: NO TRANSGENDER MUTILIZATION FOR CHILDREN! DO NOT FAIL!!!”

The proposed Safeguard American Voter Eligibility (SAVE) Act would amend the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 to require in-person proof of citizenship for anyone seeking to vote in U.S. elections. Trump has also called for the legislation to include a ban on gender-affirming medical care for transgender minors, even with parental consent.

“This is a huge priority for the president. He added on some priorities to the SAVE America Act in recent days, namely, no transgender transition surgeries for minors. We are not gonna tolerate the mutilation of young children in this country. No men in women’s sports,” White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said. “The president putting all of these priorities together speaks to how common sense they are.”

The comments mark the first time the White House has publicly confirmed that Trump is pushing to attach anti-trans policies to the SAVE Act.

The bill would also require the removal of undocumented immigrants from existing voter rolls and allow election officials who fail to enforce the proof-of-citizenship requirement to be sued.

It is already illegal for noncitizens to vote in federal elections. Current safeguards include requirements such as providing a Social Security number when registering to vote, cross-checking voter rolls with federal data and, in some states, requiring identification at the polls.

Trump began pushing for the legislation during his State of the Union address last month, where he singled out Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-S.D.) by name while criticizing the lack of movement on the bill.

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) has denounced the legislation as “Jim Crow 2.0” and said it has little chance of advancing through the Senate, calling it “dead on arrival.”

In remarks on the Senate floor, Schumer said “the SAVE Act includes such extreme voter registration requirements that, if enacted, could disenfranchise 21 million American citizens.”

Trump has repeatedly used political messaging around trans youth and gender-affirming care as part of broader cultural and policy debates during his presidency — most recently during his State of the Union address, where he cited the case of Sage Blair, a Virginia teenager whose school allegedly encouraged her to transition without her parents’ consent.

LGBTQ advocates — including those familiar with Blair’s story — say the situation was far more complex than described and argue that using a single anecdote to justify sweeping federal restrictions could place trans people, particularly youth, at greater risk.

Health

Too afraid to leave home: ICE’s toll on Latino HIV care

Heightened immigration enforcement in Minneapolis is disrupting treatment

Uncloseted Media published this article on March 3.

This story was produced in collaboration with Rewire News Group, a nonprofit publication reporting on reproductive and sexual health, rights and justice.

This story was produced with the support of MISTR, a telehealth platform offering free online access to PrEP, DoxyPEP, STI testing, Hepatitis C testing and treatment and long-term HIV care across the U.S. MISTR did not have any editorial input into the content of this story.

By SAM DONNDELINGER and CAMERON OAKES | For two weeks, Albé Sanchez didn’t leave their house in South Minneapolis.

“[I was] forced into survival mode,” Sanchez told Uncloseted Media and Rewire News Group (RNG). “I felt like there was an invisible wall [to the outside world] that I couldn’t cross unless I really wanted to put myself in a place where there was a chance that I might not be able to come back.”

Queer and Mexican American, Sanchez was afraid of being targeted by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement presence in their neighborhood, even though they are a U.S. citizen.

“Every day is a risk,” they say, adding that even if they have paperwork, if they fit the profile, they are a target, making it scary to go even to work or the grocery store.

Sanchez, a 30-year-old sexual health care educator, has been taking oral PrEP, the daily preventive medication for HIV, for over a decade. But the mounting stress of ICE raids has made it harder to keep up with dosing.

“A missed dose here and there pushed me to make the appointment [for something more sustainable],” they say.

Sanchez says they felt like somebody would have their back at their local clinic. It was only a 10-minute drive from where they worked, they knew its staff from previous visits and community outreach, and they could count on finding Spanish-speaking staff and providers of Latino heritage. But not everybody has had that same experience accessing care.

Since ICE’s Operation Metro Surge began in early December, an increasing number of Latino patients in Minnesota are delaying or canceling what can be lifesaving care for the prevention and treatment of HIV.

These findings are particularly alarming for Latino communities, who, as of 2023, are 72 percent more likely than the general U.S. population to be diagnosed with HIV. And while overall infections have decreased, cases among Latinos increased by 24 percent between 2010 and 2022.

“I’m very concerned that there is going to be a sharp uptick in transmission,” says Alex Palacios, a community health specialist in the Minneapolis area.

In a January 2026 declaration as part of a lawsuit seeking to end Operation Metro Surge in the days following Renee Nicole Good’s killing, the commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Health said HIV testing among Latino populations has “dropped dramatically” and that “although grantee staff continue to go into the community to promote and provide testing, people are not showing up.”

Local clinics are reporting the same thing. The Aliveness Project, a community wellness center in Minneapolis specializing in HIV care, told Uncloseted Media and RNG they have seen more than a 50 percent decrease in new clients. The clinic serves a large number of Latino and undocumented clients, and while it usually sees 750 people walk through their door each week, according to providers, it reported seeing 100 fewer people each week since December.

Red Door, Minnesota’s largest STI and HIV clinic, has had a “modest uptick” in no-shows and missed appointments since December.

What happens when treatment stops

Today, there are multiple medications available that work to prevent HIV and dozens that treat it once a person tests positive. Many people who consistently take their medication have such low levels of the virus that they can’t transmit it through sex. But becoming undetectable requires patients to stay on their medication; otherwise, the virus replicates and mutates, weakening the immune system and increasing the risk of life-threatening infections.

“If patients aren’t on their medicines consistently, HIV can learn about the medication and become resistant to them. When this happens, the medicine will not work for the patient, and the new resistant virus could potentially be passed on to others,” says George Froehle, a physician assistant and provider at Aliveness Project. “Medication adherence is one of the most important aspects of HIV care.”

To maintain care and prevent dangerous, untreatable strains from spreading in Minnesota, providers at Aliveness Project have begun delivering medication to patients when possible, offering telehealth when they can, and pausing routine lab work to limit in-person appointments.

“The most important thing we can do from a public health perspective is to keep people undetectable so they don’t transmit HIV,” Froehle says, adding that providers in other cities targeted by ICE will need to make plans for missed injection visits, pivot to telehealth and prepare their teams for the “trauma that can occur.”

Sanchez understands the risks of inconsistent treatment, which is why they opted for the injectable preventative medication.

“I have a lot of risk [to HIV in my community],” Sanchez says. “With so much uncertainty about the future and whether HIV care will remain stable, I realized I couldn’t let this opportunity pass.”

But injectable HIV treatments are commonly dosed at two weeks to six months apart, and the medication must be administered in a clinic — a setting many patients are avoiding, according to providers.

“They have a two-week window” to get their shots, according to Froehle, who added that because patients are afraid to come in person, they have had to transition people off of their injectable HIV treatments. This has caused patients to return to oral HIV treatments without the testing they would normally receive had ICE not been in Minneapolis. “[Oral treatments] weren’t super successful [for these patients] to begin with and that’s why they were on injectables.”

Oral HIV medications, too, must be taken consistently to work. In response, providers have urged patients to have their pills with them at all times in case they get deported or detained.

The caution is not unfounded. Federal immigration facilities have a history of denying adequate medical care to people living with HIV, despite internal standards that require them to comply. Since 2025, at least two men living with HIV have been denied access to their medication in a Brooklyn jail, according to lawsuits obtained by THE CITY. One man said he was only given his medication after his lips broke open and he developed an open pustule on his leg. And in January 2025, another man died of HIV complications while in ICE custody in Arizona.

Beyond being detained without proper medication, patients are at risk of being deported to countries with limited access to HIV care, like Honduras and Venezuela, experts say.

“A lot of men [from Venezuela] told me they left because it wasn’t safe to be gay there and because they struggled to access HIV care,” says Froehle. “It’s a little heartbreaking to see new folks not only face the threat of deportation, but to places where they didn’t feel safe medically or identity-wise.”

“Some of these patients will die in their home country,” says Anna Person, the chair of the HIV Medicine Association. “It’s a death sentence.”

A ‘cascading disaster’

While ICE’s presence is threatening the infrastructure of HIV care that Minneapolis has built over decades, experts say there has always been a blind spot in HIV care for the city’s Latino community.

Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, executive director of the Institute for Policy Solutions at the Johns Hopkins University of Nursing, describes HIV in Latino communities as a “cascading disaster,” the result of years of compounding inequities.

“There’s been an invisible crisis among Latinos that hasn’t gotten traction,” he says. “The numbers have consistently gone up in terms of new infections, while nationally they’ve gone down. … That should be a big alarm.”

Numbers are rising because structural barriers and stigma are preventing Latinos from receiving care. A 2022 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that between 2018 and 2020, nearly 1 in 4 Hispanic people living with HIV reported experiencing discrimination in health care settings. Lack of representation among providers, language barriers and deep-rooted medical mistrust further complicate access to care, according to Guilamo-Ramos.

Beyond the medical system, stigma within Latino communities can be equally damaging. According to Human Rights Campaign data, more than 78 percent of Latino LGBTQ youth reported experiencing homophobia or transphobia within the Latino community in 2024.

Sanchez agrees that stigma and bias are already massive barriers to care, citing the strict gender norms and Catholic beliefs many Latino communities hold. They say ICE’s presence is threatening already delicate access to HIV care.

“This has caused so much damage to people,” Sanchez says. “Not being able to access your health care appointments is such a stab in the side. … Being able to navigate any of these things in normal circumstances already has so much difficulty to it.”

Palacios, who is Afro-Latine and living with HIV, says the heightened ICE presence is worsening barriers that have long undermined the Latino community’s access to HIV care.

“The horizon has always been stark and dim,” they say. “And this just feels like one more thing to address and to fight back against.”

Sliding backwards

Navigating HIV care is becoming more difficult across the board, as the federal government has decimated HIV funding, compromising decades of progress made in the fight against the virus since Donald Trump retook office just over a year ago.

In February 2026, three months into Operation Metro Surge, the Trump-Vance administration proposed slashing $600 million in HIV-related grants, targeting four blue states, including $42 million for Minnesota programs. A federal judge has temporarily blocked the cuts.

“This would completely decimate and gut all of our HIV prevention,” says Dylan Boyer, director of development at Aliveness Project. “That’s the reality that we live in.”

“We have all the tools, and yet we are staring down this rollback of infrastructure and research dollars, prevention efforts, treatment efforts, that are going to put us squarely back in the 1980s,” says Person, a national HIV expert who grew up in Minnesota. “[There] seems to be no other rationale for that besides cruelty, to be quite frank, since there’s no scientific reason for it.”

Repair and representation

Jenny Harding, director of advancement at a Minneapolis-area supportive housing program for people living with HIV, says that while ICE’s presence is lessening in the Twin Cities, the “damage is done.”

Person says that this mending will take time, especially between the medical community and patients, since HIV providers can have a “very fragile” relationship with their clients.

“It takes, sometimes, years to build that level of trust. And I do worry that folks are just going to say, ‘I don’t feel safe here anymore. The system does not have my best interest at heart, and I’m not coming back,’” she says. “This is not something that you can flip a switch and everything will go back to normal.”

“We need to hold our federal government accountable, particularly HHS, [and] we need to ensure that HIV funding remains intact,” Guilamo-Ramos says, adding that in order to lower rates of HIV in the Latino community, there should be more specialized efforts: such as bilingual and culturally aligned health care providers, community-based outreach programs co-located where risk is highest, trust-building initiatives to address medical mistrust, mobile clinics, and targeted programs to re-engage patients who have fallen out of care.

Aliveness Project’s patient numbers have increased in the last few weeks as the ICE operation has waned, but the clinic staff is keeping “a watchful eye” and is having “difficulty reaching folks who are understandably scared.”

“Our biggest focus right now is reconnecting with people through our outreach so no one has a lapse in their HIV medications or prevention care,” Boyer, of Aliveness Project, says.

For Sanchez, seeing providers who speak Spanish and are of Latin heritage at Aliveness Project built enough trust for them to reach out and make an appointment despite the risks. Sanchez feels optimistic about their new injectable prevention strategy with the support of their clinic.

“There’s many places where you can receive care here in the Twin Cities where you might not see your skin tone. … There’s still a lot of health care professionals that unfortunately carry bias. … Aliveness is the opposite of that,” they say. “Seeing that representation and knowing someone has that cultural context of how to meet you in moments of sensitivity, it’s crucial.”