Arts & Entertainment

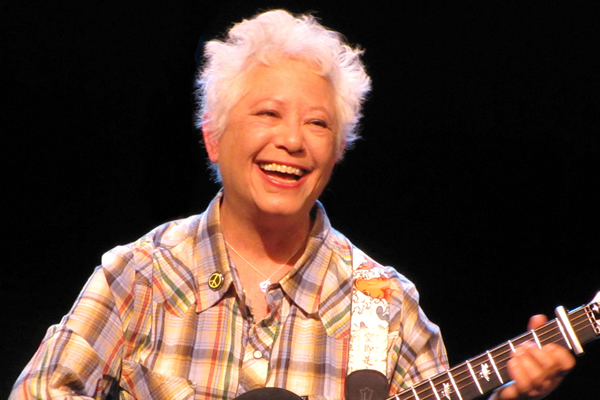

Lighting the way: an interview with singer Janis Ian

Veteran performer embarking on final tour

By my count, queer singer/songwriter Janis Ian has had four distinct chapters in her musical career. The first began when she was in her teens with the release of her groundbreaking single “Society’s Child,” and the albums on Verve Records that followed in the late 1960s. By the mid-1970s, for the second chapter, Ian signed to Columbia Records, resulting in the biggest hit single of her career, the Grammy Award-winning classic “At Seventeen.” She remained on Columbia into the early 1980s, even collaborating with Giorgio Moroder on the song “Fly Too High.” The third chapter occurred in the early 1990s. Bette Midler recorded Ian’s song “Some People’s Lives,” the title track of Bette’s Grammy-winning 1991 album. Ian herself recorded the song for her marvelous 1993 comeback album, the aptly titled “Breaking Silence.”

Ian has not been sitting idle since that time, mind you. She’s released a few more albums, including some on her own Rude Girl Records label. She also published her memoir “Society’s Child: My Autobiography” in 2008 and won her second Grammy for the audiobook. I have had the pleasure of interviewing Janis in 1994, 2004, 2008, and in 2022, and it is always a revelatory experience. She was kind enough to answer a few questions in advance of the release of her flawless new album “The Light at the End of the Line” (Rude Girl).

BLADE: I’ve been racking my brain trying to come up with the best way to say this, and I keep returning the fact that with The Light at the End of the Line, your extraordinary last solo studio album, you are going out with a bang.

JANIS IAN: [Laughs] better a bang than a whimper!

BLADE: What was involved in the decision to make this your final studio recording?

IAN: I think hitting 70 was a big part of it. Having the last 15 years to put together songs and wanting to make something that was better than anything I’d done before was involved. Mostly, the timing really worked out. I went into lockdown right around when I needed or wanted to start thinking about this. I had no plans until I looked up at my write board and realized I had 15 songs I was pleased with, and one unfinished. I started listening to what Randy Leago had done with “Resist,” and I began working with Viktor Krauss on “Better Times…” I had originally intended to do an all-solo acoustic album, but it became clear that I really wanted a blend of it to serve the songs. There wasn’t a sudden, “Gee, I’ll make an album now” decision. There was more a talking to people and seeing where Randy and Viktor’s schedules were. Seeing where John Whelan was. Whether we could get Nuala Kennedy to do her parts from Ireland. Finding a studio where I live, which is near Bradenton, so there’s not a huge amount of studios available. Then just winnowing down the songs and going, “Well, I think this is actually an album.”

BLADE: Among the many aspects that make The Light at the End of the Line exceptional is that for the 12 songs, you draw on the many influences spanning your five-decade career, beginning with “I’m Still Standing,” which is as personal as, say, “At Seventeen.”

IAN: I would say so. That was part of my goal for the entire album, and part of the winnowing down of songs, was to make sure that the songs I picked were as universal as possible, and also songs that would hopefully stand the test of time. I mean it’s incredible that “At Seventeen” was released in 1975. It’s 45 years later and it’s still getting lots of airplay. Lots of people still sing it. People are still affected by it, young people, not people anywhere close to my age. So, to make an album that would reach as many people as possible emotionally, and at the same time have songs that were as well-written as I’m capable of doing after almost 60 years as a songwriter; that was the challenge, really. So, I’m glad to hear you say that.

BLADE: The social consciousness of your music extends all the way back to “Society’s Child” and continues today with songs such as “Stranger” and “Resist.” Please say a few words about the role of social commentary in your music.

IAN: I was raised in a very political family. I grew up stuffing envelopes and going to marches. My parents were both politically aware. My mom did things like attend the Civil Rights Congress. My parents were under watch by the FBI. So, it was a natural part of my life. Everyone we knew was involved, in one way or another, in politics and social issues, because I would regard feminism as much as a social issue as a political one. Although the line between the two is pretty blurred these days as I’m sure you know. “Stranger” just came out of nowhere one night. I had an off night and I never write on the road, ever. I think I’ve written two songs in my life while I was touring. But I was changing guitar strings and came up with that little pattern and the song just fell out in the course of the evening. I’ve been thinking about it a lot because my own grandfather had to come into America on a cousin’s passport. None of us found out his real name or the story until we were in our 20s and 30s. So I started thinking with all these people saying “illegals should be deported, even if they grew up here, even if they were born here, even if they’ve lived here 40 years, where does that leave me? Should I be sent back to Poland or Russia or the Ukraine?

BLADE: It truly resonates and it’s an ongoing issue. That leads me to the next question, which is about the anthemic single “Resist,” which is one of the album’s most powerful statements, with its “I will not disappear” and titular chants. Are you ever shocked that you still find yourself having to write and perform a song such as this?

IAN: I’m shocked that it hasn’t been fixed by now [laughs], and that it seems to be getting worse. I think that in some ways my generation underestimated the determination of the powers that be to stay in power. We knew about the FBI and the CIA, but it would never have occurred to us that there would still be genital mutilation. That women would still be burned on pyres. That there would be revenge rape. It’s a shock that these things still need to be addressed, but it’s not shocking that they need to be written about. I also think that music cuts through the noise in a way that very few other things can. Politics becomes just noise. Social media becomes just noise. Music has the ability to touch people’s hearts directly in a way that none of those things can. I didn’t set out with “Resist” and think, “Oh, I’m going to write a protest song about this.” But I was plenty annoyed when I wrote it.

BLADE: That definitely comes through.

IAN: It’s a fine line for me because my voice only carries so far. I can’t do what certain singers can do with their voices. I have a relatively light voice. That’s one of the great things about Randy Leago, and what he did with it. Because he managed to leave all that space for the vocal while surrounding it with…oh, I think I had asked for angry drums. So, the first thing you hear is that thud of the bass drum, which to me is like a footstep coming into the room. Lines like “I cannot be your virgin and I will not be your whore” came out of my own experience.

BLADE: It really is an incredible song. “Nina” is a breathtaking tribute to Nina Simone. It made me think about her performance in Questlove’s 2021 documentary Summer of Soul, and how she’s being reintroduced to new generations. Have you seen the doc?

IAN: I have not seen that, but I did see the Liz Garbus documentary What Happened, Miss Simone? (from 2015) because she’s singing my song in it.

BLADE: What do you think she’d think of your song about her?

IAN: [Big laugh] I would not begin to wonder what Nina would think about anything. I wouldn’t go there for $1,000,000. Well, maybe for $1,000,000, but I would be pretty unsure of myself. Nina was monumentally easy and monumentally difficult to love. That’s what I tried to capture in the song. She was biologically ill, mentally ill, I would say, but I’m not sure what the correct phrase is these days. But there was such a big biological aspect to it and by the time that was really beginning to be understood and treated, she had already burned so many bridges and made so many people angry. I feel like I saw Nina at her best and her worst. Her best was so much better than any other performer I’ve ever watched. And her worst was pretty scary.

BLADE: As a gay man, I have always loved the story about Nina’s correspondence with Langston Hughes.

IAN: She and (James) Baldwin (were friends), too. We had lunch at my mother’s one day and she showed up with James Baldwin in tow. I don’t think she cared about that at all because artists tend not. It doesn’t really matter, it’s like skin color. Who cares as long as you’re doing great work. It’s the world that surrounds us that becomes the problem.

BLADE: That is very true! Album closer “Better Times Will Come” is the kind of uplifting number we all need at this time. I was delighted by Diane Schuur’s scat…

IAN: Isn’t she great? Deedles!

BLADE: Her “Shayna maidel” shout-out elevates the song to a different level.

IAN: We probably talk every couple of weeks or more often. We’re good buddies. She’s great.

BLADE: Was that song as much fun to record as it is to listen to?

IAN: It began out of the Better Times project that I started when lockdown began — bettertimeswillcome.com. That involved, in the end, 187 artists all doing their own versions of the song. We’ve got 13 versions still to put up! Everything from Japanese sign language interpretation to a Dutch version to a Mandarin Chinese version to banjo or guitar or flatfooting. When it came time to record it, I wanted to close the album with it, but do something completely different from what I’d done already. My version that everybody worked off for the project was just me singing the song immediately after I finished it into my phone, no guitar, no nothing. You can go to bettertimeswillcome.com and watch all those videos, see all those versions, listen to them, download them. It was a great way to promote other artists who had projects coming out and suddenly couldn’t tour or make book appearances, all of that through my Facebook page. The Facebook people were wonderfully generous. I didn’t want to repeat that or reuse it, so it became question of how I do this so that it’s totally different from anything on the album and it maintains that spirit of inclusivity. I reached out to Viktor and we literally both sat down with our phone books and went, “OK, this person would be great. That person would be great. Are they available?” Vince Gill wasn’t available because he’s out with the Eagles. We told Vince we had a two-month window and he literally turned it in three days before we went to mix. With Deedles (Schuur), she’d been in lockdown for a while. There was no nearby studio. It was working with her manager to find a studio and then coordinating it with her so that she felt safe, and she could do it in her own time, in her own way. For all the musicians, it became a question of me saying, “This is a step-out moment. Treated it like you’re in the (Tommy) Dorsey bands in the old days and he suddenly points to you and says “You take your solo. No preparation, no leading up to it, no ramping up. You just start max.” I was really pleased with it. John Cowan singing a verse to start off with. That’s not something I’ve ever been able to do, and I’ve always wanted John to sing one of my songs. The harmonies are great. People like Andrea Zonn, who’s normally out with James Taylor, because of COVID they were available. It worked for the piece. Viktor and Jared (Anderson), the young engineer he found, worked at assembling. We spent a lot of time on it. It felt like we just needed something to give us all a bit of hope, and yet to recognize COVID, which is why the ending is what it is. Because we keep thinking we’re good and then we’re not and we think we’re good and then we’re not. Trying to speak to that, as well.

BLADE: As a songwriter, you have a long history of having your songs recorded by other performers. If you had to choose one song from The Light at the End of the Line to be covered by another artist, what song would it be and who would want to hear sing it?

IAN: Oh, man, that’s pretty easy! I would have P!nk record “Resist.” I think she would slay that; I think she would just kill that song.

BLADE: Not only is The Light at the End of the Line your last studio recording but the multi-city tour on which you will be embarking throughout most of 2022 is your final North American tour. What will you miss the most and the least about touring?

IAN: The thing you miss about touring when you’re not touring is the audience. I have really good audiences. Everything from the male or female seven-year-old would-be guitarist whose parent or grandparent thinks “You should see a really good acoustic guitarist” to the 80-year-old person who’s been following me since “Society’s Child.” It’s a really broad range. I meant it when I said (in the album art) that “this album is a love song” because when I wrote (the song) “The Light at the End of the Line” I looked at it as what I was saying to my fans. One of the difficult possibilities that artists face in these days of social media and easy advertising is making sure that you consider your supporters. A word I prefer to fans, because “fans” has other connotations. The people who have always supported me — I go back to Facebook as an example – there’s a social media everybody said you can’t make money from. And yet, one year when we held the sale for our Pearl Foundation, 70% of the money came from Facebook followers. I have to believe that if you do as I’ve done; if you don’t accept advertising on your page, if you don’t bother people, if you just present yourself and have a good time, they stay with you. I have more than half a million followers to attest to that. There are a lot of potential pitfalls that I try to avoid because I really respect the people who support my work. That’s an absurd cliché, Gregg, but it’s true. I respect those people. I have a lot of gratitude toward those people.

BLADE: Do you have a feeling that they know that?

IAN: Absolutely! When I was staying after every show and signing, which I did for 30 years, I would hear that. That was very direct. The Light at the End of the Line also becomes a way for me to say, “You stuck with me when I was not a great writer. You stuck with me when I didn’t really know what I was doing, and I grew up in this fishbowl. Here’s our payoff. I am now a really good writer and singer, and here’s a love song for you.

BLADE: The last couple of years have been brutal, to say the least, and we lost many great friends and artists, including Nanci Griffith and John Prine. Would you mind saying a few words about Nanci and John?

IAN: Nanci was a very under-recognized songwriter, like Dolly Parton. And a great interpreter. She called me one day and said, “Janis, I need a Janis Ian folk song.” [Laughs] “I don’t know what that means” and she said, “Just let it roll around.” I called my friend Jon Vezner and I said, “Nanci Griffith wants a Janis Ian folk song and I have this idea for something that’ll begin ‘This old town should have burned down in 1929’,” and he said, “Fantastic! I’ll be over tomorrow morning.” That’s how Nanci operated. She left you to do what you do. John’s death really took me aback. It hit me very hard. It’s not that we were that close, but I had known John since we’re both in our early 20s. We had seen each other at the Cambridge Folk Festival a little short while before, or it felt like a short while before. “Better Times Will Come” literally grew out of that. I was in our house, in the garage doing laundry, thinking about John. “Better times will come” started running through my head. I wrote it, basically, because John died. I’m not sure what I would have written without that. Somebody once said to me, “You will never be able to write a three-chord song.” Gregg, this is literally the only three-chord song I have written in my life. I have to think that on some level, without getting weird about it, John was out there encouraging it. He was the king of simplicity. John was simple and direct in a way that very few of us ever get to be. (He’s) sorely missed.

The 44th annual Queen of Hearts pageant was held at The Lodge in Boonsboro, Md. on Friday, Feb. 20. Six contestants vied for the title and Bev was crowned the winner.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

View on Threads

Books

New book profiles LGBTQ Ukrainians, documents war experiences

Tuesday marks four years since Russia attacked Ukraine

Journalist J. Lester Feder’s new book profiles LGBTQ Ukrainians and their experiences during Russia’s war against their country.

Feder for “The Queer Face of War: Portraits and Stories from Ukraine” interviewed and photographed LGBTQ Ukrainians in Kyiv, the country’s capital, and in other cities. They include Olena Hloba, the co-founder of Tergo, a support group for parents and friends of LGBTQ Ukrainians, who fled her home in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha shortly after Russia launched its war on Feb. 24, 2022.

Russian soldiers killed civilians as they withdrew from Bucha. Videos and photographs that emerged from the Kyiv suburb showed dead bodies with their hands tied behind their back and other signs of torture.

Olena Shevchenko, chair of Insight, a Ukrainian LGBTQ rights group, wrote the book’s forward.

The book also profiles Viktor Pylypenko, a gay man who the Ukrainian military assigned to the 72nd Mechanized Black Cossack Brigade after the war began. Feder writes Pylypenko’s unit “was deployed to some of the fiercest and most important battles of the war.”

“The brigade was pivotal to beating Russian forces back from Kyiv in their initial attempt to take the capital, helping them liberate territory near Kharkiv and defending the front lines in Donbas,” wrote Feder.

Pylypenko spent two years fighting “on Ukraine’s most dangerous battlefields, serving primarily as a medic.”

“At times he felt he was living in a horror movie, watching tank shells tear his fellow soldiers apart before his eyes,” wrote Feder. “He held many men as they took their final breaths. Of the roughly one hundred who entered the unit with him, only six remained when he was discharged in 2024. He didn’t leave by choice: he went home to take care of his father, who had suffered a stroke.”

Feder notes one of Pylypenko’s former commanders attacked him online when he came out. Pylypenko said another commander defended him.

Feder also profiled Diana and Oleksii Polukhin, two residents of Kherson, a port city in southern Ukraine that is near the mouth of the Dnieper River.

Ukrainian forces regained control of Kherson in November 2022, nine months after Russia occupied it.

Diana, a cigarette vender, and Polukhin told Feder that Russian forces demanded they disclose the names of other LGBTQ Ukrainians in Kherson. Russian forces also tortured Diana and Polukhin while in their custody.

Polukhim is the first LGBTQ victim of Russian persecution to report their case to Ukrainian prosecutors.

Feder, who is of Ukrainian descent, first visited Ukraine in 2013 when he wrote for BuzzFeed.

He was Outright International’s Senior Fellow for Emergency Research from 2021-2023. Feder last traveled to Ukraine in December 2024.

Feder spoke about his book at Politics and Prose at the Wharf in Southwest D.C. on Feb. 6. The Washington Blade spoke with Feder on Feb. 20.

Feder told the Blade he began to work on the book when he was at Outright International and working with humanitarian groups on how to better serve LGBTQ Ukrainians. Feder said military service requirements, a lack of access to hormone therapy and documents that accurately reflect a person’s gender identity and LGBTQ-friendly shelters are among the myriad challenges that LGBTQ Ukrainians have faced since the war began.

“All of these were components of a queer experience of war that was not well documented, and we had never seen in one place, especially with photos,” he told the Blade. “I felt really called to do that, not only because of what was happening in Ukraine, but also as a way to bring to the surface issues that we’d had seen in Iraq and Syria and Afghanistan.”

Feder also spoke with the Blade about the war’s geopolitical implications.

Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2013 signed a law that bans the “promotion of homosexuality” to minors.

The 2014 Winter Olympics took place in Sochi, a Russian resort city on the Black Sea. Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine a few weeks after the games ended.

Russia’s anti-LGBTQ crackdown has continued over the last decade.

The Russian Supreme Court in 2023 ruled the “international LGBT movement” is an extremist organization and banned it. The Russian Justice Ministry last month designated ILGA World, a global LGBTQ and intersex rights group, as an “undesirable” organization.

Ukraine, meanwhile, has sought to align itself with Europe.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy after a 2021 meeting with then-President Joe Biden at the White House said his country would continue to fight discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. (Zelenskyy’s relationship with the U.S. has grown more tense since the Trump-Vance administration took office.) Zelenskyy in 2022 publicly backed civil partnerships for same-sex couples.

Then-Ukrainian Ambassador to the U.S. Oksana Markarova in 2023 applauded Kyiv Pride and other LGBTQ and intersex rights groups in her country when she spoke at a photo exhibit at Ukraine House in D.C. that highlighted LGBTQ and intersex soldiers. Then-Kyiv Pride Executive Director Lenny Emson, who Feder profiles in his book, was among those who attended the event.

“Thank you for everything you do in Kyiv, and thank you for everything that you do in order to fight the discrimination that still is somewhere in Ukraine,” said Markarova. “Not everything is perfect yet, but you know, I think we are moving in the right direction. And we together will not only fight the external enemy, but also will see equality.”

Feder in response to the Blade’s question about why he decided to write his book said he “didn’t feel” the “significance of Russia’s war against Ukraine” for LGBTQ people around the world “was fully understood.”

“This was an opportunity to tell that big story,” he said.

“The crackdown on LGBT rights inside Russia was essentially a laboratory for a strategy of attacking democratic values by attacking queer rights and it was one as Ukraine was getting closet to Europe back in 2013, 2014,” he added. “It was a strategy they were using as part of their foreign policy, and it was one they were using not only in Ukraine over the past decade, but around the world.”

Feder said Republicans are using “that same strategy to attack queer people, to attack democracy itself.”

“I felt like it was important that Americans understand that history,” he said.

More than a dozen LGBTQ athletes won medals at the Milan Cortina Winter Olympics that ended on Sunday.

Cayla Barnes, Hilary Knight, and Alex Carpenter are LGBTQ members of the U.S. women’s hockey team that won a gold medal after they defeated Canada in overtime. Knight the day before the Feb. 19 match proposed to her girlfriend, Brittany Bowe, an Olympic speed skater.

French ice dancer Guillaume Cizeron, who is gay, and his partner Laurence Fournier Beaudry won gold. American alpine skier Breezy Johnson, who is bisexual, won gold in the women’s downhill. Amber Glenn, who identifies as bisexual and pansexual, was part of the American figure skating team that won gold in the team event.

Swiss freestyle skier Mathilde Gremaud, who is in a relationship with Vali Höll, an Austrian mountain biker, won gold in women’s freeski slopestyle.

Bruce Mouat, who is the captain of the British curling team that won a silver medal, is gay. Six members of the Canadian women’s hockey team — Emily Clark, Erin Ambrose, Emerance Maschmeyer, Brianne Jenner, Laura Stacey, and Marie-Philip Poulin — that won silver are LGBTQ.

Swedish freestyle skier Sandra Naeslund, who is a lesbian, won a bronze medal in ski cross.

Belgian speed skater Tineke den Dulk, who is bisexual, was part of her country’s mixed 2000-meter relay that won bronze. Canadian ice dancer Paul Poirier, who is gay, and his partner, Piper Gilles, won bronze.

Laura Zimmermann, who is queer, is a member of the Swiss women’s hockey team that won bronze when they defeated Sweden.

Outsports.com notes all of the LGBTQ Olympians who competed at the games and who medaled.