Obituary

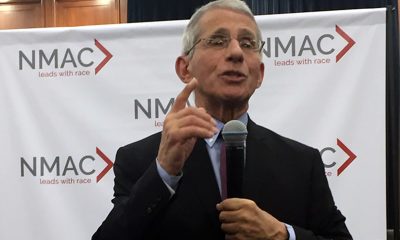

Art history professor, longtime D.C. resident Tom Hardy dies at 81

Colleagues say his courses were ‘legendary’

Thomas W. “Tom” Hardy, a professor of art history who also taught English and the humanities at the Annandale Campus of Northern Virginia Community College for 40 years and whose colleagues and many students considered his art history courses as “legendary,” died Oct. 30 at the age of 81.

Friends and family members said the cause of death was complications associated with sepsis.

In addition to teaching art history, English, and humanities for students at Northern Virginia Community College, which college officials refer to as NOVA, Hardy offered art appreciation courses for community members through the college’s Lifetime Learning Institution, according to a statement released by the college.

The statement says Hardy also conducted numerous trips for students and NOVA colleagues to the art capitals of Europe and taught an undergraduate seminar on European Baroque Art at D.C.’s George Washington University.

“Professor Hardy’s colleagues remember him as a witty and erudite gentleman,” J.K. Daniels, dean of Languages, Arts, and Social Sciences at the Annandale Campus, said in the statement. “His former dean noted that ‘Professor Hardy was a devoted teacher whose students praised him for the passion he exhibited for his subjects,’” Daniels said.

“His art history courses were legendary, brim-filled with images from his own photography collection and others,” said Daniels.

“A gifted professor, his lectures for courses in English, art history and humanities drew upon a rich background in literature, music, philosophy, and religions,” according to two other colleagues at NOVA, Duncan Tebow, former Dean and Art Professor Emeritus; and Betsy Tebow, Art History Professor Emeritus.

“His scholarly interests and publications ranged from Constantine era tombs and Palladian villas to 20th century abstraction,” the two said. “He also supported college art programs, organizing student art shows, and arranging lectures by visiting scholars. Tom was always a warm, witty, bright presence on campus, generous with his time and talents,” they said.

Hardy was born and raised in Washington, D.C., where he lived nearly all his life, friends and family members said. His nephew, Greg DeLuca, said Hardy and his domestic partner of 50 years, Carl Spier, lived for more than 20 years in a townhouse in the Capitol Hill East neighborhood on the same street where Hardy lived as a child with his parents while growing up.

Coming from a Catholic family, he graduated from D.C.’s Catholic Gonzaga High School. DeLuca and Spier believe Hardy received his undergraduate degree from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill before receiving his master’s degree in English at UNC Chapel Hill. He earned a master’s in art history degree from George Washington University, DeLuca said.

DeLuca said Hardy worked for a short time at the Library of Congress before embarking on his teaching career at NOVA. The NOVA statement provided to the Washington Blade says Hardy’s tenure as a professor there began in 1970 and continued through 2009 at the time of his retirement.

Friends said Hardy and partner Spier regularly attended the Sunday Catholic Mass offered by D.C.’s LGBTQ Catholic organization Dignity Washington.

One longtime friend, David Lambdin, said he and others enjoyed going with Hardy to D.C. art museums, including the National Gallery of Art, where Hardy provided insight and “opened my eyes to what I was seeing.”

DeLuca said that in retirement Hardy did a lot of traveling with Spier throughout Europe as well as Egypt. Friends said Hardy also continued organizing art history trips to Italy and other European nations, for friends and family members.

DeLuca describes Hardy as a “great” uncle who was “generous, happy, sarcastic, witty, and smart” and who would brighten a room.

“I had many talks with him in his last few months while bedridden,” DeLuca said. “He wasn’t bitter. He told me he had a very good life with no real regrets.”

Spier stated in a Facebook posting that Hardy passed away at the Ashby Ponds assisted living and retirement facility in Ashburn, Va., where he and Spier had been living for the past few years while Hardy was under treatment for sepsis.

“My friend and companion for over 50 years, I loved him and will miss him forever,” Spier wrote.

Hardy’s ashes were interred at a graveside ceremony at Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hillcrest Heights, Md., on Dec. 3. Dignity Washington held a memorial Mass in Hardy’s honor the following day on Dec. 4, at St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church. Father Alexei Michelanko presided over the Mass, which was followed by a celebration of life gathering at the church’s fellowship hall.

“In his 81 years, Tom lived a full life and touched many people,” Michelanko said. “He spent those years not simply concerned with himself but being of service to others primarily as that of art historian. And in the process, he was beautifying his own life, with passion, pleasure, and joy.”

Hardy is survived by his partner of 50 years Carl Spier; his younger sister Merrill Breighner; his brother-in-law Tom DeLuca; five nieces and nephews, including Greg DeLuca, Christine DeLuca, Karen Devore, Joe Breighner, and Emily Kowalski; and many friends, including David Lambdin of Arlington, Va. and Larry Smelser of Baltimore. He is predeceased by his sisters Maryanne Hardy and Elizabeth DeLuca.

Obituary

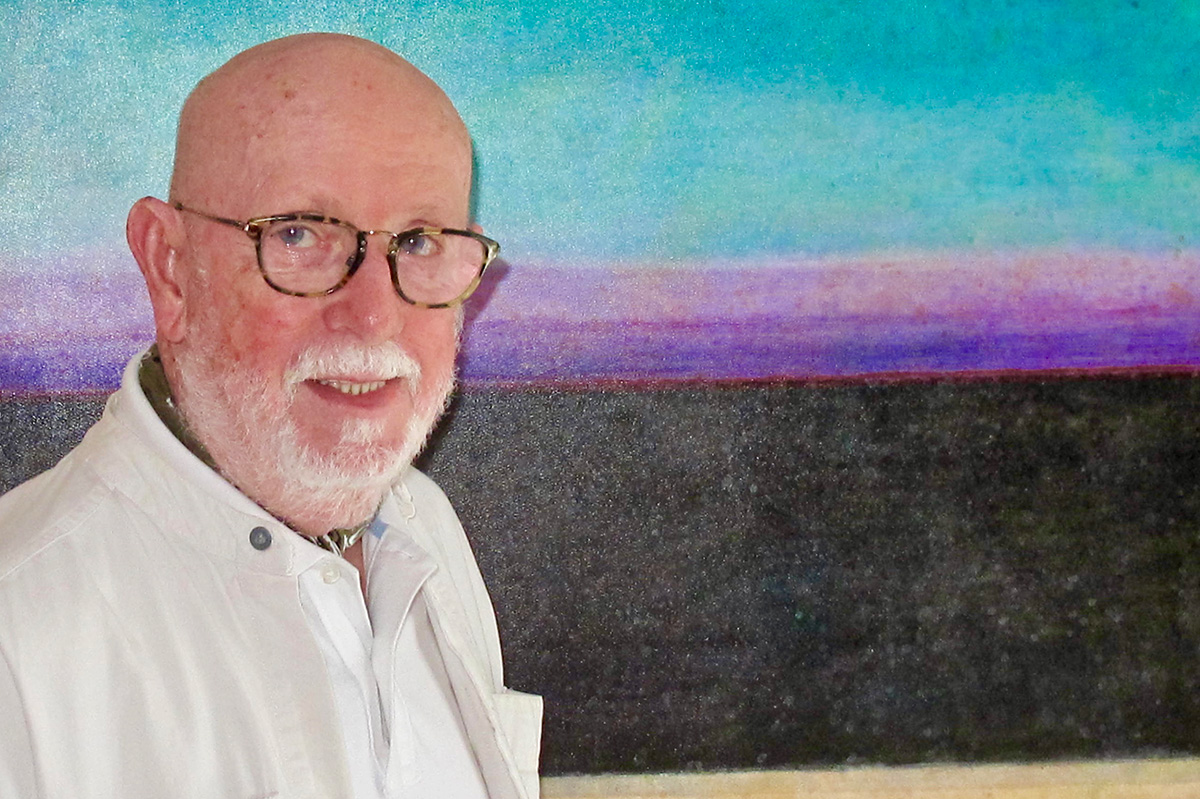

Longtime DC resident Thomas Walsh dies at 87

Pa. native’s husband was by his side when he passed away

Long-time D.C. resident Thomas Walsh died on May 16. He was 87.

Walsh was born on Sept. 17, 1937, in Scranton, Pa. His family later moved to Levittown, Pa.

Walsh met his husband, Anthony Carcaldi, at the Blue Note, a gay bar in Asbury Park, N.J., in 1964.

“I walked in the bar with friends from New York City,” recalled Carcaldi. “I looked at the piano and this person was singing … and all I noticed were his blue eyes.”

Walsh was singing “Because of You.”

“I walked up to the piano while Tom was singing and stared at him, which caused him to forget the words,” said Carcaldi. “He composed himself and started from the beginning.”

Carcaldi and Walsh became a couple in 1965, a year after they met, when they moved to Philadelphia.

“We moved in together and have been together ever since,” said Carcaldi.

Walsh was a freelance graphic designer until he accepted a job in Temple University’s audiovisual department. Walsh and Carcaldi moved to D.C. in 1980.

Walsh began a graphic design business and counted Booz Allen as among his clients. Carcaldi said one of his husband’s “main loves was painting,” and became a fine artist in 2005.

Walsh showed his art at the Nevin Kelly Gallery on U Street, the Martha Spak Studio near the Wharf, and at the Wexler Gallery in Philadelphia. Walsh also sang with the Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington.

Walsh and Carcaldi married at D.C. City Hall in 2014.

“Tom and I have been together since 1964 until his death,” said Carcaldi. “Tom died peacefully with me at his side in bed on May 16, 2025, holding Tom in my arms as he made the transition out of life.”

A celebration of life will take place in September.

Obituary

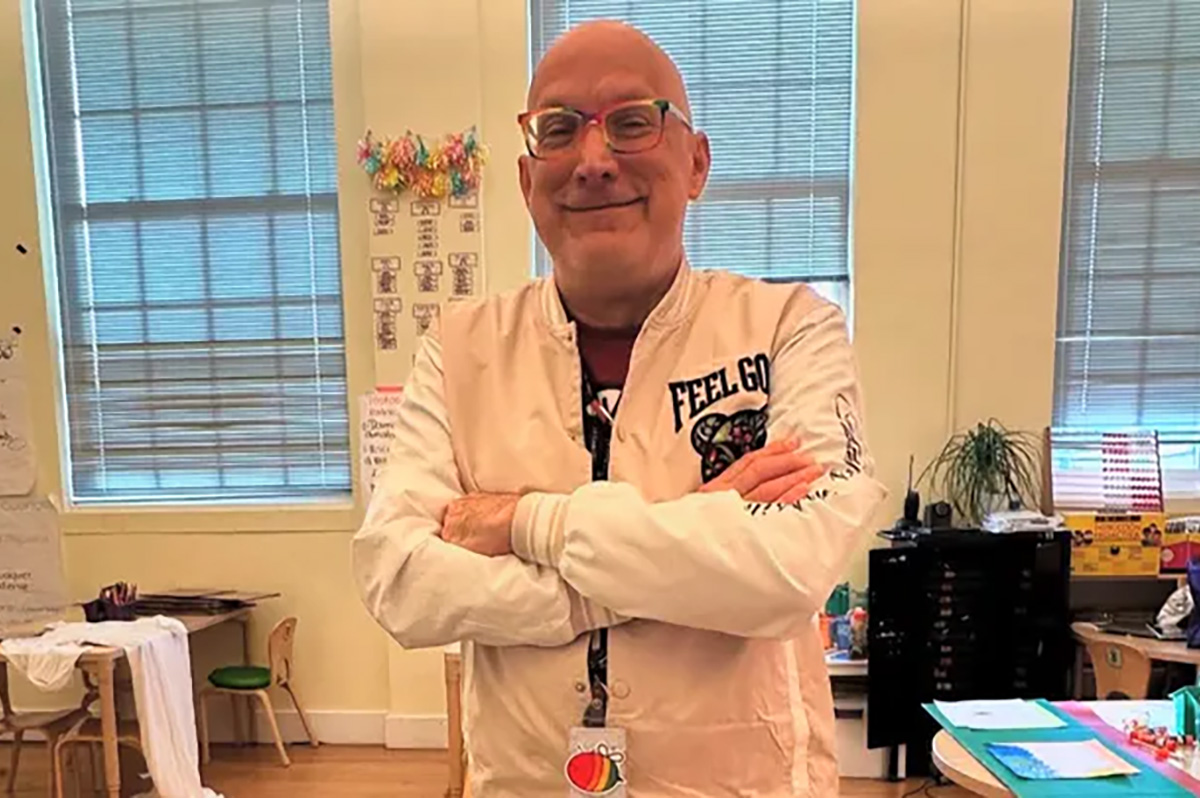

Beloved schoolteacher, D.C. resident Patrick Shaw dies at 60

Colleagues, friends say he ‘touched so many lives’ with warmth, kindness

Patrick Dewayne Shaw, a highly acclaimed elementary school teacher who taught and served as vice principal in several D.C. schools since moving to the District in 2002, died April 19 at the age of 60.

His friend Dusty Martinez said his passing was unexpected and caused by a heart related ailment.

“Patrick touched so many lives with his warmth, humor, kindness, and unmistakable spark,” Martinez said in a statement. “He was a truly special soul – funny, vibrant, sassy, and full of life, and we are heartbroken by his loss,” Martinez wrote.

Among those reflecting on Shaw’s skills as an educator were his colleagues at D.C.’s Mundo Verde Bilingual Public Charter School, where he served as a second-grade special education teacher since August 2023.

“Patrick brought warmth, joy, and deep commitment to Mundo Verde,” his colleagues said in an Instagram posting. “His daily Broadway sing-alongs, vibrant outfits, and genuine love for his students filled our community with energy and laughter,” the posting says.

Biographical information provided by Martinez and Karen Rivera Geating, a senior inclusion manager at the Mundo Verde school and Shaw’s supervisor, shows Shaw had a distinguished 38-year teaching career and multiple degrees in the field of education.

He was born and raised in Little Rock, Ark., and graduated from Little Rock’s Catholic High School for Boys.

He received two bachelor’s degrees, one in philosophy from St. Meinrad Seminary College in Indiana and one in elementary education from the University of Minnesota in St. Paul.

The biographical information shows Shaw received three master’s degrees. One is in secondary education and history from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. His second master’s degree is in special education from The Catholic University of Washington, D.C. His third master’s degree is in school administration from Trinity College in D.C.

Shaw began his teaching career in 1987 in Little Rock, Ark., as a fourth grade General Education Teacher at Our Lady of Good Counsel School and a short time later at Little Rock’s St. Theresa Catholic School as a fourth-eighth grade teacher through December 1989.

He next moved to Minnesota where he spent part of the 1990s as a fifth and sixth grade teacher and a physical education instructor, according to biographical information. His resume shows that from January 1995 to December 1998 he was associated with the Minnesota AIDS Project in Minneapolis.

He “recruited, interviewed and staffed volunteer education and transportation programs for people living with HIV and AIDS,” his resume states.

Shaw next returned to Little Rock where he served from January 1998 to December 2004 as Theology Department Chair at the Mt. St. Mary Academy. His work included creating theology lessons for ninth-12th graders and creating a social justice program for 12th graders.

Upon moving to D.C., Shaw served as classroom teacher and vice principal at several schools, including the D.C. Public School’s Benning Elementary School; vice principal at Chavez Prep Public Charter School; vice principal at Bridges Public Charter School; Special Education Coordinator at Monument Academy Public Charter School; and Special Education Case Management and Math Intervention Specialist at D.C.’s College Preparatory Academy for Boys.

“Patrick dedicated 38 wonderful years to teaching, from 1987 to 2025, inspiring generations of students with his passion, wit, and kindness,” Martinez said in his statement.

Shaw was predeceased by his mother, Myrna G. Shaw, and is survived by his father, Thomas H. Shaw, his brother, James Shaw (Michele), his sister, Angela Mahairi (Wafai), and his cherished niece and nephews Austin, Tariq, Reed, Ramy, and Jasmine, according to information provided by Martinez.

Martinez said a funeral mass would soon be held in Little Rock, Shaw’s hometown.

“His family will be honoring one of his last wishes,” Martinez wrote, “to be returned home and remembered in a unique and meaningful way” – by having a tree planted in his honor, “a living tribute to the full and beautiful life he lived.”

Details of the location of the planted tree will be shared soon to offer a place where “friends and family can visit, reflect, and stay connected with his spirit,” Martinez states.

In D.C. a celebration of life for Shaw is scheduled to be held Saturday, May 3, from 2-5 p.m. at JR.’s bar at 1519 17th Street, N.W. Martinez points out that the tribute will be held during JR.’s weekly Saturday “Showtunes” event, in which sing-along performances of famous Broadway musicals are shown on video screens.

“JR.’s Saturday Showtunes were one of Patrick’s absolute favorite traditions, and gathering in that spirit feels like the perfect way to honor him,” Martinez said.

“Many have asked how they can help,” Martinez concludes in his statement. “In response we’ve created a GoFundMe page to support funeral expenses, help find a loving home for Patrick’s beloved dog, Birdie, and assist with other needs during this difficult time.”

Any remaining funds, according to Martinez, will be donated to a charity “that reflects Patrick’s passions and values.”

The GoFundMe page can be accessed at: gofundme.com/f/honoring-patrick-shaws-vibrant-legacy.

Obituary

Local attorney, LGBTQ rights advocate Dale Sanders dies at 75

Acclaimed lawyer credited with advancing legal rights for people with HIV/AIDS

Dale Edwin Sanders, an attorney who practiced law in D.C. and Northern Virginia for more than 40 years and is credited with playing a key role in providing legal services for people living with HIV/AIDS beginning in the early 1980s, died April 10 at the age of 75.

His brother, Wade Sanders, said the cause of death was a heart attack that occurred at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore shortly after he had back surgery.

Wade Sanders described his brother as a “trial lawyer, passionate criminal defense, and civil litigator for human rights” for close to 50 years, with some of his work focused on “civil law, notably gay-related insurance discrimination during the AIDS epidemic.”

He called his brother “a zealous advocate for the oppressed, his clients, and his personal convictions.”

Born in Arlington, Va., and raised in McLean, Va., Dale Sanders graduated from Langley High School in McLean and received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Virginia, his brother said. He received his law degree from D.C.’s American University Washington College of Law and began his law practice in 1976 in Old Town, Alexandria, Wade Sanders said.

Amy Nelson, director of Legal Services for D.C. ‘s Whitman-Walker Health, said Sanders became one of Whitman-Walker’s original volunteer pro-bono attorneys in the 1980s.

“Dale was a beloved part of the legal services program and our medical-legal partnership for nearly 40 years,” Nelson said. “Dale was one of the clinic’s first volunteer attorneys at Whitman-Walker’s weekly, legal walk-in clinic offering free counseling to clients about their legal rights in the face of HIV/AIDS and LGBT discrimination from employers, landlords, medical providers, and insurance companies,” according to Nelson.

Nelson added, “Dale represented dozens of people impacted by the ignorance and prejudice attendant to an HIV/AIDS diagnosis, and his litigation wins were instrumental in advancing the legal rights of persons living with HIV/AIDS.”

Sanders’s most recent case on behalf of Whitman-Walker took place in 2023 in support of a transgender woman in Virginia who faced discrimination from her employer and health insurer, Nelson said.

In 1989, Whitman-Walker presented Sanders with its Gene Frey Award for Volunteer Service, and in 1994 presented him with its Founders Award for Pro Bono Legal Services, Nelson told the Blade. She said in 2024, Whitman-Walker re-named its annual Going the Extra Mile Pro Bono Award as the Dale Sanders Award for Pro Bono Excellence.

“Dale’s legacy helped to shape HIV/AIDS law, and his fierce commitment to justice will live on at Whitman-Walker Health,” Nelson said in a statement. “We will miss him dearly.”

Daniel Bruner, who served as Whitman-Walker’s legal services director prior to Amy Nelson taking that position, said Sanders played a role in shaping his own legal skills and knowledge.

“Dale was one of my earliest legal models among local, and national, advocates for people living with HIV and LGBT people,” Bruner told the Blade. “He was a fierce, persistent advocate for his clients and for the community,” Bruner said, adding, “He won key victories in several cases where employees’ or health care patients’ privacy had been egregiously violated. I certainly will never forget him.”

Wade Sanders said his brother was also an avid bridge player, saying he played competitively. “He earned the rank of Ruby Life Master, a pretty big deal in the bridge world,” Wade Sanders said.

Dale Sanders is survived by his husband, Christian Samonte; his sister, Joyce Sanders of York, S.C.; his brother Wade Sanders of West Jefferson, N.C.; and his beloved dogs Langley and Abigail, his brother said in a statement.

A memorial service for Dale Sanders organized by the Sanders family and the LGBTQ Catholic group Dignity Washington will be held Saturday, May 10, at 1 p.m. at St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church at 1830 Connecticut Ave., N.W. in D.C., a Dignity Washington spokesperson said.

-

U.S. Supreme Court3 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court3 days agoSupreme Court to consider bans on trans athletes in school sports

-

Out & About3 days ago

Out & About3 days agoCelebrate the Fourth of July the gay way!

-

Virginia3 days ago

Virginia3 days agoVa. court allows conversion therapy despite law banning it

-

Federal Government5 days ago

Federal Government5 days agoUPenn erases Lia Thomas’s records as part of settlement with White House