Movies

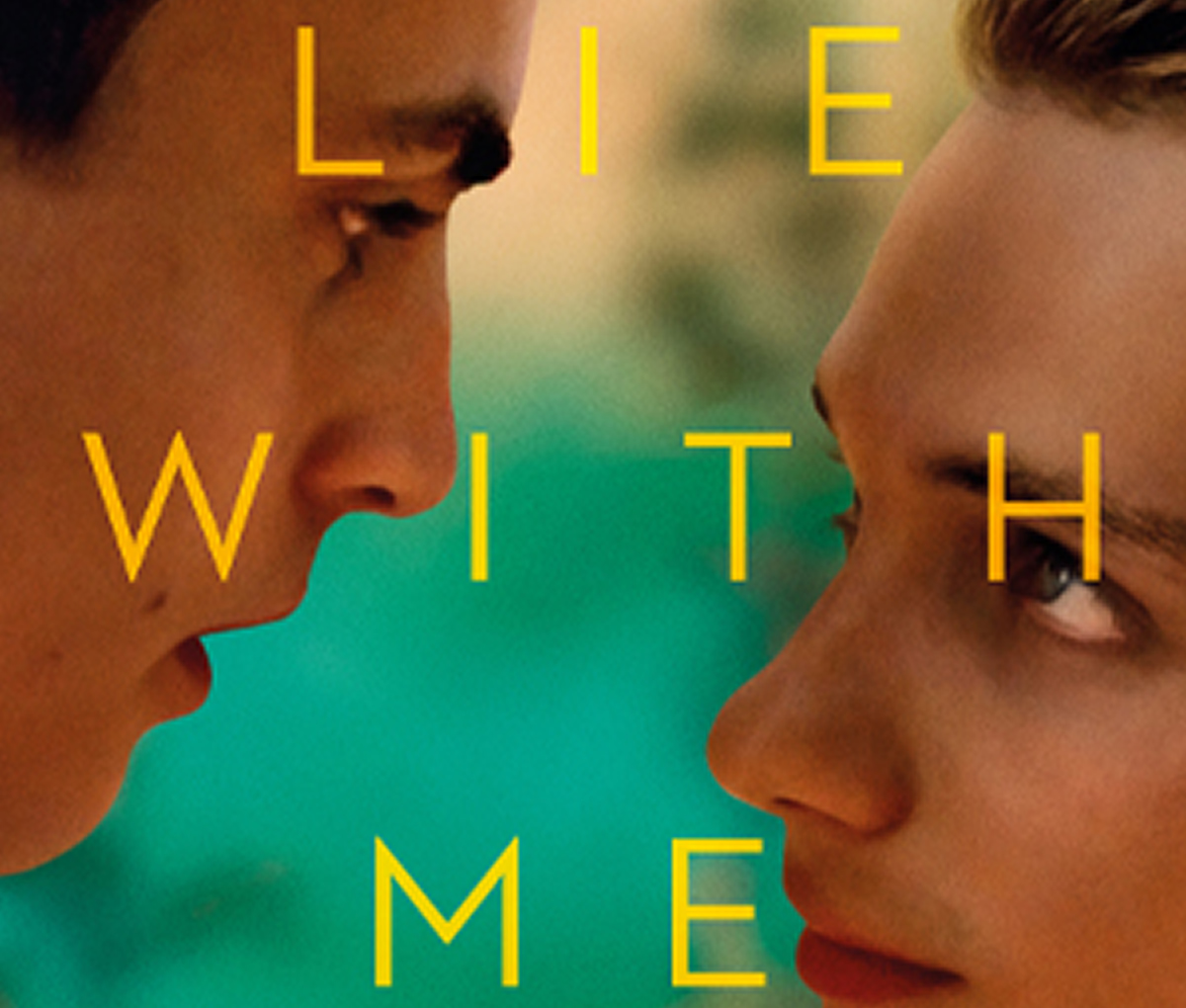

Exploring queer romance in ‘Lie with Me’

French film reminds us not to waste our lives out of fear

Why do so many gay love stories have sad endings? The new French film “Lie with Me,” based on Philippe Besson’s novel, follows this familiar theme. Although recent films have ventured away from tragedy, like “Love, Simon,” the portrayal of queer love between men often denies us a happy ending. “Brokeback Mountain” tugged at our heartstrings, and the closing shot of a tearful Elio in “Call Me By Your Name” is iconic.

It’s not surprising that many gay love stories are tinged with melancholy. In fact, there’s even a book on the subject, “The Queer Art of Failure.” In a society that, until recently, rejected the legitimacy and rights of queer love, many gay writers and filmmakers felt there was no salvation at the end of the rainbow. The AIDS crisis further clouded the outlook for gay love. However, it’s a reflection of the more optimistic times we live in that contemporary gay films and TV shows, such as “Heartstopper,” can envision storybook romances.

“Lie with Me,” a love story between French 17-year-olds set in the mid-1980s, all but rules out a happy ending. Add to the mix the rural conservative values and the inevitably divergent paths awaiting the bookish Stephane and the farm boy Thomas, and you’ve set the stage for great passion and a heartbreaking finale.

Watching this movie, it’s hard not to reminisce about your first crush and the idealized dreams you once had. For those of us of a certain age, those dreams often remained in the realm of imagination. Thomas and Stephane are fortunate to experience moments like skinny dipping in an old flooded quarry, dancing in their underwear, and making love in hidden spots. They start as a mismatched pair, with Thomas initially showing interest only in sex. However, slowly they form a bond—a love that’s innocent and uncomplicated, a kind that young hearts are perfectly suited for. Stephane envisions a world beyond the small town, but Thomas is skeptical about the continuation of their journey.

The film shifts between the young Stephane and his older self, now a renowned French novelist. Upon returning to his small town, the elder Stephane spots a young man who bears a striking resemblance to Thomas. This encounter, as the film later reveals, is far from coincidental— it’s Thomas’s son, Lucas, trying to unravel his father’s early life. It’s evident that Stephane has immortalized his teenage love in a novel, setting the stage for the gradual revelation of a tragic love affair as Stephane and Lucas share fragments of the past that form a complete picture.

One of the most significant tragedies in queer lives is the un-lived life — the men and women who, out of fear and shame, choose to remain hidden, denying themselves true love, an authentic life, and happiness. Many succumb to suicide, addiction, or other forms of abuse, while others live silently and joylessly. You might wish you could shake them and say, “You have one life to live, and you cannot let other people’s ignorance and prejudice rob you of it!” But for some, the obstacles to coming out seem insurmountable, including the fear of losing family and employment opportunities. This tragedy, while less common in today’s Western societies, persists in countries where being gay can lead to arrest or even execution.

What sets “Lie with Me” apart from other gay love stories that leave us feeling despondent is that its tragedy extends beyond the personal — it serves as an indictment of a society that forces people to suppress their most innate feelings and endure immense suffering. It offers a cautionary lesson to any gay person struggling with the fear of coming out: Do not waste your life because you are afraid of what others may think. The number of queer individuals who have lived unfulfilled lives is immeasurable. “Lie with Me” pays a posthumous tribute to them, reminding us that who they truly were should not completely vanish. And in this film, it doesn’t.

Movies

Two new documentaries highlight trans history

‘I’m Your Venus’ on Netflix, ‘Enigma’ on HBO/Max

One of the most telling things about queer history is that so much of it has to be gleaned by reading between the lines.

There are the obvious tentpoles: the activism, the politics, the names and accomplishments of key cultural heroes. Without the stories of lived experience behind them, however, these things are mere information; to connect with these facts on a personal level requires relatable everyday detail — and for most of our past, such things could only be discussed in secret.

In recent decades, thanks to increased societal acceptance, there’s been a new sense of academic “legitimacy” bestowed upon the scholarship of queer history, and much has been illuminated that was once kept in the dark. The once-repressed expressions of our queer ancestors now allow us to see our reflections staring back at us through the centuries, and connect us to them in a way that feels personal.

One of the most effective formats for building that connection, naturally enough, is documentary filmmaking — an assertion illustrated by two new docs, each focused on figures whose lives are intertwined with the evolution of modern trans culture.

“I’m Your Venus,” now streaming on Netfllix, bookends an iconic documentary from the past: “Paris is Burning (1990), Jennie Livingston’s seminal portrait of New York City’s ballroom scene of the ‘80s, In that film, a young trans woman named Venus Xtravaganz delivered first-person confessionals for the camera that instantly won the hearts of audiences — only for them to break with the shattering revelation that she had been murdered before the film’s completion.

That 1988 murder was never solved, but Venus — whose surname was Pellagatti before she joined the House of Xtravaganza – was never forgotten; four decades later, her family (or rather, families) want some answers, and filmmaker Kimberly Reed follows her biological siblings — Joe, Louie, and John, Jr. — as they connect with her ballroom clan in an effort to bring closure to her loss; with the help of trans advocates, they succeed in getting her murder case re-opened, and work to achieve a posthumous legal name change to honor her memory and solidify her legacy.

It’s a remarkably kind and unapologetically sentimental chronicle of events, especially considering the brutal circumstances of Venus’ killing — a brutal death by strangling, almost certainly perpetrated by a transphobic “john” who left her body hidden under a mattress in a seedy hotel — and her decision to leave her birth family for a chosen one. As to the latter, there are no hard feelings among her blood relatives, who assert — mostly convincingly — that they always accepted her for who she was; one senses that a lot of inner growth has contributed to the Pallagatti clan’s mission, which admittedly sometimes resembles an attempt at making amends. For the murder itself, it’s best to leave that part of the story unspoiled — though it’s fair to say that any answers which may or may not have been found are overshadowed by the spirit of love, dignity, and determination that underscore the search for them, however performative some of it might occasionally feel. Ultimately, Venus is still the star of the show, her authentic and unvarnished truth remaining eloquent despite the passage of more than 40 years.

Perhaps more layered and certainly more provocative, documentarian Zackary Drucker’s “Enigma” (now streaming on HBO/Max) delves further back into trans history, tracing the parallel lives of two women — trans pioneer and activist April Ashley and self-styled European “disco queen” Amanda Lear — whose paths to fame both began in Paris of the 1950s, where they were friends and performers together at Le Carrousel, a notorious-and-popular drag cabaret that attracted the glitterati of Europe.

Ashley — who died at 86 in 2021 — was a former merchant seaman from Liverpool whose “underground” success as a drag performer funded a successful gender reassignment surgery and led to a career as a fashion model, as well as her elevation-by-wedding into British high society — though the marriage was annulled after she was publicly outed by a friend, despite her husband’s awareness of her trans identity at the time of their marriage. She went on to become a formidable advocate for trans equality — and for environmental organizations like Greenpeace — who would earn an MBE for her efforts, and wrote an autobiography in which she shared candid stories about her experiences and relationships as part of the “exotic” Parisian scene from which she launched her later life.

The other figure profiled by “Enigma” — and possibly the one to which its title most directly refers — is Amanda Lear, who also (“allegedly”) started her rise to fame at Le Carrousel before embarking on a later career that would include fashion modeling, pop stardom, and a long-term friendship with surrealist painter Salvador Dalí. A self-proclaimed “disco queen” whose success in Europe never quite spread to American culture, despite highly public relationships and collaborations with musical icons like David Bowie and Roxy Music, Lear’s trajectory has taken her in a different direction than Ashley’s. In the film’s extensive live interview segments, she repeatedly denies and discredits suggestions of her trans identity, sticking to a long-maintained script in which any and all details of her origins are obscured and denied as a matter of course.

At times, it’s almost amusing to observe her performative (there’s that word again) denials, which occasionally approach a kind of deliberate “camp” absurdity in their adamance, but there’s also a kind of grudging respect that’s inspired by the sheer doggedness with which she insists on controlling the narrative — however misguided it may seem to those of us on the outside. Debate about her gender-at-birth has continued for decades, even predating Ashley’s book, so the movie’s “revelations” are hardly new, nor even particularly controversial — but her insistence on discrediting them provides sharp contrast with the casual candor of Ashley’s elegantly confident persona, underscoring the different responses to transphobia that would direct the separate lives of both these former (alleged) friends.

For what it’s worth, Lear sent an email to the Washington Post, calling the movie “a pathetic piece of trash” and denying not just her trans identity but any friendship or association with Ashley, despite ample photographic and anecdotal evidence to the contrary — and while it might come across as callous or desperate for her to maintain the presumed façade, it’s a powerful testament to the power of cultural bullying to suppress the truth of queer existence; the contrast between the life each of these women chose to live speaks volumes, and makes “Enigma” into one of the most interesting — and truthful — trans documentaries to emerge thus far.

While neither film presents a comprehensive or definitive view of trans experience (is such a thing even possible, really?), both offer a perspective on the past which both honors the truth of queer existence and illustrates the ways in which the stigma imposed by mainstream prejudice can shape our responses to the identity through which the public perceives us.

That makes them both worth your attention, especially when our queer history — and the acknowledgement of trans existence itself — is at risk or being rolled right back up into the closet.

Movies

20 years later, we still can’t quit ‘Brokeback Mountain’

Iconic love story returns to theaters and it’s better than you remember

When “Brokeback Mountain” was released in 2005, the world was a very different place.

Now, as it returns to the big screen (beginning June 20) in celebration of its 20th anniversary, it’s impossible not to look at it with a different pair of eyes. Since its release, marriage equality has become the law of the land; queer visibility has gained enough ground in our popular culture to allow for diverse queer stories to be told; openly queer actors are cast in blockbuster movies and ‘must-see’ TV, sometimes even playing queer characters. Yet, at the same time, the world in which the movie’s two “star-crossed” lovers live – a rural, unflinchingly conservative America that has neither place nor tolerance for any kind of love outside the conventional norm – once felt like a place that most of us wanted to believe was long gone; now, in a cultural atmosphere of resurgent, Trump-amplified stigma around all things diverse, it feels uncomfortably like a vision of things to come.

For those who have not yet seen it (and yes, there are many, but we’re not judging), it’s the epic-but-intimate tale of two down-on-their-luck cowboys – Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) and Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhall) – who, in 1963 Wyoming, take a job herding sheep on the titular mountain. There’s an unmistakable spark between them, and during their months-long shared isolation in the beautiful-but-harsh wilderness, they become lovers. They part ways when the job ends and go on about their lives; Ennis resolutely settles into a hardscrabble life with a wife (Michelle Williams) and kids, while Jack struggles to make ends meet as a rodeo rider until eventually marrying the daughter (Anne Hathaway) of a wealthy Texas businessman. Yet even as they struggle to maintain their separate lives, they reconnect, escaping together for “fishing trips” to continue their forbidden affair across two decades, even as the inevitable pressures and consequences of living a double life begin to take their toll.

Adapted from a novella by Annie Proulx, (in an Oscar-winning screenplay by co-producer Diana Ossana and acclaimed novelist Larry McMurtry), and helmed by gifted Taiwanese filmmaker Ang Lee (also an Oscar winner), the acclaim it earned two decades ago seems as well-deserved as ever, if not more so. With Lee bringing an “outsider’s eye” to both its neo-western setting and its distinctly American story of stolen romance and cultural repression, “Brokeback” maintains an observational distance, uninfluenced by cultural assumptions, political narratives, or traditional biases. We experience Ennis and Jack’s relationship on their terms, with the purely visceral urgency of instinct; there are no labels, neither of them identifies as “queer” – in fact, they both deny it, though we know it’s likely a feint – nor do they ever mention words like “acceptance, “equality,” or “pride.” Indeed, they have no real vocabulary to describe what they are to each other, only a feeling they dare not name but cannot deny.

In the sweeping, pastoral, elegiac lens of Lee’s perceptive vision, that feeling becomes palpable. It informs everything that happens between them, and extends beyond them to impact the lives they are forced to maintain apart from each other. It’s a feeling that’s frequently tormented, sometimes violent, and always passionate; and while they never speak the word to each other, the movie’s famous advertising tagline defines it well enough: “Love is a force of nature.”

Yet to call “Brokeback” a love story is to ignore its shadow side, which is essential to its lasting power. Just as we see love flowing through the events and relationships we observe, we also witness the resistant force that opposes it, working in the shadows and twisting it against itself, compelling these men to hide themselves in fear and shame behind the presumed safety of heterosexual marriage, wreaking emotional devastation on their wives, and eventually driving a wedge between them that will bring their story to (spoiler alert, if one is required for a 20-year-old film) a heartbreaking conclusion.

That opposing force, of course, is homophobia, and it’s the hidden – though far from invisible – villain of the story. Just as with Romeo and Juliet, it’s not love that creates the problem; it’s hate.

As for that ending, it’s undeniably a downer, and there are many gay men who have resisted watching the movie for all these years precisely because they fear its famously tragic outcome will hit a little too close to home. We can’t say we blame them.

For those who can take it, however, it’s a film of incandescent beauty, rendered not just through the breathtaking visual splendor of Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography, but through the synthesis of all its elements – especially the deceptively terse screenplay, which reveals vast chasms of feeling in the gaps between its homespun words, and the effectiveness of its cast in delivering it to performance. Doubtless the closeness between most of its principal players was a factor in their chemistry – Ledger and Gyllenhall were already friends, and Ledger and Williams began a romantic relationship during filming which would lead to the birth of their daughter, just before the movie’s premiere. Both Williams and Hathaway remain grounded in the truth of their characters, each of them earning our empathy and driving home the point that they are victims of homophobia, too.

As for the two stars, their chemistry is deservedly legendary. Ledger’s tightly strung, barely-articulate Ennis is a masterclass in “method” acting for the screen, with Gyllenhall’s brighter, more open-hearted Jack serving in perfectly balanced contrast. They are yin and yang to each other, and when they finally consummate their desires in that infamous and visceral tent scene, what we remember is the intensity of their passion, not the prurient details of their coupling – which are, in truth, more suggested than shown. Later, when growing comfort allows them to be tender with each other, it feels just as authentic. Both actors were outspoken allies, and though neither identified as gay or bisexual, their comfort and openness to the emotional (as well as physical) authenticity of the love story they were cast to play is evident in every moment they spend on the screen. It’s impossible to think of the movie being more perfect with anyone else but them.

As iconic as its starring pair have become, however, what made “Brokeback” a milestone was the challenge it threw in the face of accepted Hollywood norms, simply by telling a sympathetic story about same-sex love without judgment, stereotype, identity politics, or any agenda beyond simple humanistic compassion. It was the most critically acclaimed film of the year, and one of the most financially successful; though it lost the Oscar for Best Picture (to “Crash,” widely regarded as one of the Academy’s most egregious errors), it hardly mattered. The precedent had been set, the gates had been opened, and the history of queer cinema in mainstream Hollywood was forevermore divided into two eras – before and after “Brokeback Mountain.”

Still, its “importance” is not really the reason to revisit it all these years later. The reason is that, two decades later, it’s still a beautiful, deeply felt and emotionally resonant piece of cinema, and no matter how good you thought it was the first time, it’s even better than you remember it.

It’s just that kind of movie.

There was a time, early in his career, that young filmmaker Wes Anderson’s work was labeled “quirky.”

To describe his blend of dry humor, deadpan whimsy, and unresolved yearning, along with his flights of theatrical fancy and obsessive attention to detail, it seemed apt at the time. His first films were part of a wave when “quirky” was almost a genre unto itself, constituting a handy-but-undefinable marketing label that inevitably became a dismissive synonym for “played out.”

That, of course, is why every new Wes Anderson film can be expected to elicit criticism simply for being a Wes Anderson film, and the latest entry to his cinematic canon is, predictably, no exception.

“The Phoenician Scheme” – released nationwide on June 6 – is perhaps Anderson’s most “Anderson-y” movie yet. Set in the exact middle of the 20th Century, it’s the tall-tale-ish saga of Anatole “Zsa-Zsa” Korda (Benicio del Toro), a casually amoral arms dealer and business tycoon with a history of surviving assassination attempts. The latest – a bomb-facilitated plane crash – has forced him to recognize that his luck will eventually run out, and he decides to protect his financial empire by turning it over (on a trial basis, at least) to his estranged daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton), currently a novice nun on the verge of taking her vows. She conditionally agrees, despite the rumors that he murdered her mother, and is drawn into an elaborate geopolitical con game in which he tries to manipulate a loose cadre of “world-building” financiers (Tom Hanks, Bryan Cranston, Riz Ahmed, Mathieu Amalric, and Jeffrey Wright) into funding a massive infrastructure project – already under construction – across the former Phoenician empire.

Joined by his new administrative assistant and tutor, Bjorn (Michael Cera), Korda and Liesl travel the world to meet with his would-be investors, dodging assassination attempts along the way. His plot is disrupted, however, by the clandestine interference of a secret coalition of nations led by an American agent code-named “Excalibur” (Rupert Friend), who seeks to prevent the shift of geopolitical power his project would create. Eventually, he’s forced to target a final “mark” – his ruthless half-brother Nubar (Benedict Cumberbatch), with whom he has played a lifelong game of “who can lick who” – for the money he needs to pull it off, or he’ll lose his fortune, his oligarchic empire, and his slowly improving relationship with his daughter, all at once.

It’s clear from that synopsis that Anderson’s scope has widened far beyond the intimate stories of his earliest works – “Bottle Rocket,” “Rushmore,” “The Royal Tenenbaums,” and others, which mostly dealt with relationships and dynamics among family (or chosen family) – to encompass significantly larger themes. So, too, has his own singular flavor of filmmaking become more fully realized; his exploration of theatrical techniques within a cinematic setting has grown from the inclusion of a few comical set-pieces to a full-blown translation of the real world into a kind of living, efficiently-modular Bauhaus diorama, where the artifice is emphasized rather than suggested, and realism can only be found through the director’s unconventionally-adjusted focus.

His work is no longer “quirky” – instead, it has grown with him to become something more pithy, an extension of the surreal and absurdist art movements that exploded in the tense days before World War II (an era which bears a far-too-uncomfortable resemblance to our own) and expresses the kind of politically-aware philosophical ideas that helped to build the world which has come since. It is no longer possible to enjoy a Wes Anderson movie on the basis of its surface value alone; it is necessary to read deeper into his now-well-honed cinematic language, which is informed not just by his signature aesthetic but by intellectual curiosity, and by the art, history, and cultural knowledge with which he saturates his work – like pieces of a scattered puzzle, waiting to be picked up and assembled along the way. Like all auteurs, he makes films that are shaped by a personal vision and follow a personal logic; and while he may strive to make them entertaining, he is perhaps more interested in providing insight into the wildly contradictory, often nonsensical, frequently horrifying, and almost always deplorable behavior of human beings. Indeed, the prologue scene in his latest endeavor illustrates each of those things, shockingly and definitively, before the opening credits even begin.

By typical standards, the performances in “Phoenician Scheme” – like those in most of Anderson’s films – feel stylized, distant, even emotionally cold. But within his meticulously stoic milieu, they are infused with a subtle depth that comes as much from the carefully maintained blankness of their delivery as it does from the lines themselves. Both del Toro and Threapleton manage to forge a deeply affecting bond while maintaining the detachment that is part of the director’s established style, and Cera – whose character reveals himself to be more than he appears as part of the story’s progression – begs the question of why he hasn’t become a “Wes Anderson regular” long before this. As always, part of the fun comes from the appearances of so many familiar faces, actors who have become part of an ever-expanding collection of regular players – including most-frequent collaborator Bill Murray, who joins fellow Anderson troupers Willem Dafoe and F. Murray Abraham as part of the “Biblical Troupe” that enact the frequent “near-death” episodes experienced by del Toro’s Korda throughout, and Scarlett Johansson, who shows up as a second cousin that Korda courts for a marriage of financial convenience – and the obvious commitment they bring to the project beside the rest of the cast.

But no Anderson film is really about the acting, though it’s an integral part of what makes them work – as this one does, magnificently, from the intricately choreographed opening credit sequence to the explosive climax atop an elaborate mechanical model of Korda’s dream project. In the end, it’s Anderson himself who is the star, orchestrating his thoroughly-catalogued vision like a clockwork puzzle until it pays off on a note of surprisingly un-bittersweet hope which reminds us that the importance of family and personal bonds is, in fact, still at the core of his ethos.

That said, and a mostly favorable critical response aside, there are numerous critics and self-identified fans who have been less than charmed by Anderson’s latest opus, finding it a redundant exercise in a style that has grown stale and offers little substance in exchange. Frankly, it’s impossible not to wonder if they have seen the same movie we have.

“The Phoenician Scheme,” like all of its creator’s work, is ultimately an esoteric experience, a film steeped in language and concepts that may only be accessible to those familiar with them – which, far from being a means of shutting out the “unenlightened,” aims instead to entice and encourage them to think, to explore, and, perhaps, to expand their perspective. It might be frustrating, but the payoff is worth it.

In this case, the shrewd political and economical realities he illuminates behind the romanticized “Hollywood” intrigue and his deceptively eccentric presentation speak so profoundly to the current state of world we live in that, despite its lack of directly queer subject matter, we’re giving it our deepest recommendation.

-

U.S. Supreme Court2 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court2 days agoSupreme Court to consider bans on trans athletes in school sports

-

Out & About2 days ago

Out & About2 days agoCelebrate the Fourth of July the gay way!

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoSilver Spring holds annual Pride In The Plaza

-

Opinions5 days ago

Opinions5 days agoSupreme Court decision on opt outs for LGBTQ books in classrooms will likely accelerate censorship