Local

Will the Slowe-Burrill House become a National Landmark?

Process raises questions about what constitutes LGBTQ history

On Oct. 5, 2020, the Slowe-Burrill House was put on the National Register for Historic Places for its association with Lucy Diggs Slowe, most recognized for her work as the first Dean of Women at Howard University, where she served from 1922 until her death in 1937.

Even before her appointment at Howard, she boasted an extraordinary vitae. As an undergraduate at Howard, she was a founding member of the first sorority for African-American women. After graduating valedictorian of her class, and earning her master’s at Columbia University, Slowe took a position teaching at the Armstrong Manual High School in D.C., where she so impressed the school board that they appointed her to found the first-ever junior high school for African Americans in the national capital region.

As Tamara Beauboeuf-Lafontant describes in her book-length study of Slowe’s deanship, “To Live More Abundantly,” Slowe’s tenure at Howard was defined by her advocacy for what she called the “New Howard Woman” in her inaugural address to the students, a woman who was “of extreme culture and refinement.” She worked tirelessly, often at odds with the administration, to encourage the women of Howard to pursue the social sciences, not just the liberal arts thought to befit future mothers, and to explore careers outside of teaching, which was, as Slowe described, “the only occupation which is open to them with few handicaps.” Slowe was unsatisfied with the absence of women’s housing on campus, which she argued was necessary as a “laboratory for practical education in human relationships,” and orchestrated funding from Congress to build three new dormitories for a Women’s Campus. Slowe was so successful in her projects that, as one student reported, “we spoke among ourselves of our dean, not as Dean Slowe but as Dean Swift.”

Given Slowe’s remarkable life, and the National Park Service’s registration of her house as a historic site in recognition of that life, one would be forgiven for wondering why the site is titled the “Slowe-Burrill House” after both Slowe and her life partner, Mary Burrill. While the National Register nods to Burrill’s career as a teacher and playwright, it makes clear her historical significance is primarily as Slowe’s partner. The title of the site is less in recognition of Burrill herself than of Slowe and Burrill’s same-sex relationship at a time in which it would have been especially risky for a public figure like Slowe. While Slowe and Burrill were able to frame their partnership within 19th century ideals of romantic friendship, those ideals were coming under increasing scrutiny by the 20th century, which saw the pathologizing of women’s intimate relationships in the growing medical discourse around sexuality.

Now the Slowe-Burrill House is up for nomination as a National Landmark at the next meeting of the National Historic Landmark Committee this spring. Dr. Susan Ferentinos, a specialist in LGBTQ public history, was contacted by the National Park Service back in 2016 to help identify potential landmarks related to LGBTQ history. Ferentinos noticed there was a particular absence of LGBTQ landmarks in D.C., and put together a shortlist of sites including the Slowe-Burrill House. Ferentinos has been working through that list since, most recently preparing a national landmark nomination for the Furies Collective, which the Blade reported on in November.

But the bar for a National Historic Landmark is far higher than for the National Register of Historic Places. Only 3% of items on the National Register earn a further designation as a National Historic Landmark, and the priority for federal funding that goes with it. Will the Slowe-Burrill House meet that higher bar?

One way a site gets approved is by association with a nationally significant figure, and Lucy Diggs Slowe certainly has the national standing required. As Dean of Women, her work extended far beyond the campus of Howard University. Slowe established the National Association of College Women, an alumnae organization for Black women college graduates across the country. Under her leadership, the organization raised money to help young Black women attend college, worked to institutionalize gender equity in higher education, and led initiatives to foster interracial understanding with white college alumnae. Slowe was the first Black member of the National Association of Deans of Women, where she endlessly fielded her white peers’ concerns with racial matters on campus. And Slowe served on the national board of Young Women’s Christian Association, which gave her the connections she needed to go on a cross-country tour of colleges to talk about race relations among college women.

But if Slowe’s impact on women’s and African-American history on a national level is undoubtable, things are less clear when it comes to her mark on LGBTQ history. Slowe’s relationship with Burrill was a private matter, and not one she sought to advertise on the national stage. If Slowe’s house becomes a national landmark, will it still be as the Slowe-Burrill House? Or just the Slowe House?

That question arose early in Ferentinos’s work with Kathryn Smith, the National Historic Landmarks Coordinator for the Capital Region. On an early draft for the nomination, Dr. Ferentinos got the feedback that perhaps Slowe wasn’t really a national figure in LGBTQ history, and that they should be focusing on other criteria of national significance. But Ferentinos, who made it clear she does not speak for the National Park Service, vehemently disagreed. “I said to [Kathryn Smith], I feel so strongly that this property is significant to LGBTQ history. What this feedback is telling me is that I haven’t done a good enough job yet. I’m willing to do a couple extra rounds of revision … in order to do this right because it is really important.”

As Dr. Ferentinos sees it, LGBTQ history is often simply figured as a history of political activism, which excludes the huge number of folks who managed to carve out a professional life while leading a life as LGBTQ, however private it may have been. And if she’s ever going to get a chance to nominate someone who represents this broader vision of LGBTQ history, it’s Slowe.

It is well known that at the end of her career, Slowe had a protracted fight with the president of Howard University, Mordecai Johnson. Despite having arranged in her contract to live off-campus, as all male deans did, Johnson was intent on forcing Slowe to live on campus, so that she could better supervise the students — and from a shanty next to the college dump. Slowe fought Johnson to defend her contract right up until her death. While Slowe was dying from pneumonia in her bed, instead of appointing an interim dean, Johnson issued her an ultimatum: report to work or be replaced. Burrill refused to answer the demand, and a replacement was named. Slowe died a month later, on Oct. 21, 1937.

As Beauboeuf-Lafontant describes it in her book, this story is yet another example of Slowe’s fight for gender equality, to have the rights and privileges afforded to male deans. But while Beauboeuf-Lafontant makes no mention of the role Slowe’s relationship with Burrill played in this tale, Ferentinos thinks it was a central factor. “There are memos that could seem very innocent [to] a historian who is not trained in LGBTQ history,” Ferentinos explained. There would be a memo, for instance, asking Slowe to give an account of the financial hardship the move would cause her. “It could seem like a bureaucratic crossing of Ts,” Ferentinos said. “Or it could be read as calling her bluff. It wouldn’t cause her a financial hardship, it would cause her partner a financial hardship.”

Kathryn Smith reported being satisfied with Ferentinos’s revisions of the nomination, but was cautious about predicting whether or not they would succeed. “We are supportive of the arguments she’s making, but it will ultimately be up to the NHL [National Historic Landmark] committee to determine and to make the recommendation as to whether this argument will stand.” At stake here is more than just Slowe. Is LGBTQ history just the history of figures who publicly advocated the rights of queer people? Or is it also the history of those who worked to build whatever life they could, no matter how private they kept it?

(CJ Higgins is a postdoctoral fellow with the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute at Johns Hopkins University.)

District of Columbia

D.C. police arrest man for burglary at gay bar Spark Social House

Suspect ID’d from images captured by Spark Social House security cameras

D.C. police on Feb. 18 arrested a 63-year-old man “of no fixed address” for allegedly stealing cash from the registers at the gay bar Spark Social House after unlawfully entering the bar at 2009 14th St., N.W., around 12:04 a.m. after it had closed for business, according to a police incident report.

“Later that day officers canvassing for the suspect located him nearby,” a separate police statement says. “63-year-old Tony Jones of no fixed address was arrested and charged with Burglary II,” the statement says.

The police incident report states that the bar’s owner, Nick Tsusaki, told police investigators that the bar’s security cameras captured the image of a man who has frequently visited the bar and was believed to be homeless.

“Once inside, the defendant was observed via the establishment’s security cameras opening the cash register, removing U.S. currency, and placing the currency into the left front pocket of his jacket,” the report says.

Tsusaki told the Washington Blade that he and Spark’s employees have allowed Jones to enter the bar many times since it opened last year to use the bathroom in a gesture of compassion knowing he was homeless. Tsusaki said he is not aware of Jones ever having purchased anything during his visits.

According to Tsusaki, Spark closed for business at around 10:30 p.m. on the night of the incident at which time an employee did not properly lock the front entrance door. He said no employees or customers were present when the security cameras show Jones entering Spark through the front door around 12:04 a.m.

Tsusaki said the security camera images show Jones had been inside Spark for about three hours on the night of the burglary and show him taking cash out of two cash registers. He took a total of $300, Tsusaki said.

When Tsusaki and Spark employees arrived at the bar later in the day and discovered the cash was missing from the registers they immediately called police, Tsusaki told the Blade. Knowing that Jones often hung out along the 2000 block of 14th Street where Spark is located, Tsusaki said he went outside to look for him and saw him across the street and pointed Jones out to police, who then placed him under arrest.

A police arrest affidavit filed in court states that at the time they arrested him police found the stolen cash inside the pocket of the jacket Jones was wearing. It says after taking him into police custody officers found a powdered substance in a Ziploc bag also in Jones’s possession that tested positive for cocaine, resulting in him being charged with cocaine possession in addition to the burglary charge.

D.C. Superior Court records show a judge ordered Jones held in preventive detention at a Feb. 19 presentment hearing. The judge then scheduled a preliminary hearing for the case on Feb. 20, the outcome of which couldn’t immediately be obtained.

District of Columbia

Judge rescinds order against activist in Capital Pride lawsuit

Darren Pasha accused of stalking organization staff, board members, volunteers

A D.C. Superior Court judge on Feb.18 agreed to rescind his earlier ruling declaring local gay activist Darren Pasha in default for failing to attend a virtual court hearing regarding an anti-stalking lawsuit brought against him by the Capital Pride Alliance, the group that organizes D.C.’s annual Pride events.

The Capital Pride lawsuit, initially filed on Oct. 27, 2025, accuses Pasha of engaging in a year-long “course of conduct” of “harassment, intimidation, threats, manipulation, and coercive behavior” targeting Capital Pride staff, board members, and volunteers.

In his own court filings without retaining an attorney, Pasha has strongly denied the stalking related allegations against him, saying “no credible or admissible evidence has been provided” to show he engaged in any wrongdoing.

Judge Robert D. Okum nevertheless on Feb. 6 approved a temporary stay-away order requiring Pasha to stay at least 100 feet away from Capital Pride’s staff, volunteers, and board members until the time of a follow-up court hearing scheduled for April 17. He reduced the stay-away distance from 200 yards as requested by Capital Pride.

In his two-page order issued on Feb. 18, Okun stated that Pasha explained that he was involved in a scooter accident in which he was injured and his phone was damaged, preventing him from joining the Feb. 6 court hearing.

“Therefore, the court finds there is a good cause for vacating the default,” Okun states in his order.

At the time he initially approved the default order at the Feb. 6 hearing that Pasha didn’t attend, Okun scheduled an April 17 ex parte proof hearing in which Capital Pride could have requested a ruling in its favor seeking a permanent anti-stalking order against Pasha.

In his Feb. 18 ruling rescinding the default order Okun changed the April 17 ex parte proof hearing to an initial scheduling conference hearing in which a decision on the outcome of the case is not likely to happen.

In addition, he agreed to consider Pasha’s call for a jury trial and gave Capital Pride 14 days to contest that request. The Capital Pride lawsuit initially called for a non-jury trial by judge.

One request by Pasha that Okum denied was a call for him to order Capital Pride to stop its staff or volunteers from posting information about the lawsuit on social media. Pasha has said the D.C.-based online blog called DC Homos, which Pasha claims is operated by someone associated with Capital Pride, has been posting articles portraying him in a negative light and subjecting him to highly negative publicity.

“The defendant has not set forth a sufficient basis for the court to restrict the plaintiff’s social media postings, and the court therefore will deny the defendant’s request in his social media praecipe,” Okun states in his order.

A praecipe is a formal written document requesting action by a court.

Pasha called the order a positive development in his favor. He said he plans to file another motion with more information about what he calls the unfair and defamatory reports about him related to the lawsuit by DC Homos, with a call for the judge to reverse his decision not to order Capital Pride to stop social media postings about the lawsuit.

Pasha points to a video interview on the LGBTQ Team Rayceen broadcast, a link to which he sent to the Washington Blade, in which DC Homos operator Jose Romero acknowledged his association with Capital Pride Alliance.

Capital Pride Executive Director Ryan Bos didn’t immediately respond to a message from the Blade asking whether Romero was a volunteer or employee with Capital Pride.

Pasha also said he believes the latest order has the effect of rescinding the temporary stay away order against him approved by Okun in his earlier ruling, even though Okun makes no mention of the stay away order in his latest ruling. Capital Pride attorney Nick Harrison told the Blade the stay away order “remains in full force and effect.”

Harrison said Capital Pride has no further comment on the lawsuit.

District of Columbia

Trans activists arrested outside HHS headquarters in D.C.

Protesters demonstrated directive against gender-affirming care

Authorities on Tuesday arrested 24 activists outside the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services headquarters in D.C.

The Gender Liberation Movement, a national organization that uses direct action, media engagement, and policy advocacy to defend bodily autonomy and self-determination, organized the protest in which more than 50 activists participated. Organizers said the action was a response to changes in federal policy mandated by Executive Order 14187, titled “Protecting Children from Chemical and Surgical Mutilation.”

The order directs federal agencies and programs to work toward “significantly limiting youth access to gender-affirming care nationwide,” according to KFF, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that provides independent, fact-based information on national health issues. The executive order also includes claims about gender-affirming care and transgender youth that critics have described as misinformation.

Members of ACT UP NY and ACT UP Pittsburgh also participated in the demonstration, which took place on the final day of the public comment period for proposed federal rules that would restrict access to gender-affirming care.

Demonstrators blocked the building’s main entrance, holding a banner reading “HANDS OFF OUR ‘MONES,” while chanting, “HHS—RFK—TRANS YOUTH ARE NO DEBATE” and “NO HATE—NO FEAR—TRANS YOUTH ARE WELCOME HERE.”

“We want trans youth and their loving families to know that we see them, we cherish them, and we won’t let these attacks go on without a fight,” said GLM co-founder Raquel Willis. “We also want all Americans to understand that Trump, RFK, and their HHS won’t stop at trying to block care for trans youth — they’re coming for trans adults, for those who need treatment from insulin to SSRIs, and all those already failed by a broken health insurance system.”

“It is shameful and intentional that this administration is pitting communities against one another by weaponizing Medicaid funding to strip care from trans youth. This has nothing to do with protecting health and everything to do with political distraction,” added GLM co-founder Eliel Cruz. “They are targeting young people to deflect from their failure to deliver for working families across the country. Instead of restricting care, we should be expanding it. Healthcare is a human right, and it must be accessible to every person — without cost or exception.”

Despite HHS’s efforts to restrict gender-affirming care for trans youth, major medical associations — including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Endocrine Society — continue to regard such care as evidence-based treatment. Gender-affirming care can include psychotherapy, social support, and, when clinically appropriate, puberty blockers and hormone therapy.

The protest comes amid broader shifts in access to care nationwide.

NYU Langone Health recently announced it will stop providing transition-related medical care to minors and will no longer accept new patients into its Transgender Youth Health Program following President Donald Trump’s January 2025 executive order targeting trans healthcare.

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoTrump falsely links trans people to terrorism

-

Virginia5 days ago

Virginia5 days agoFellow lawmakers praise Adam Ebbin after Va. Senate farewell address

-

National5 days ago

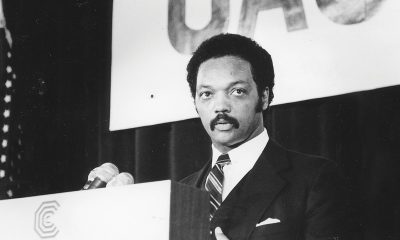

National5 days agoLGBTQ activists mourn the Rev. Jesse Jackson

-

Massachusetts4 days ago

Massachusetts4 days agoEXCLUSIVE: Markey says transgender rights fight is ‘next frontier’