National

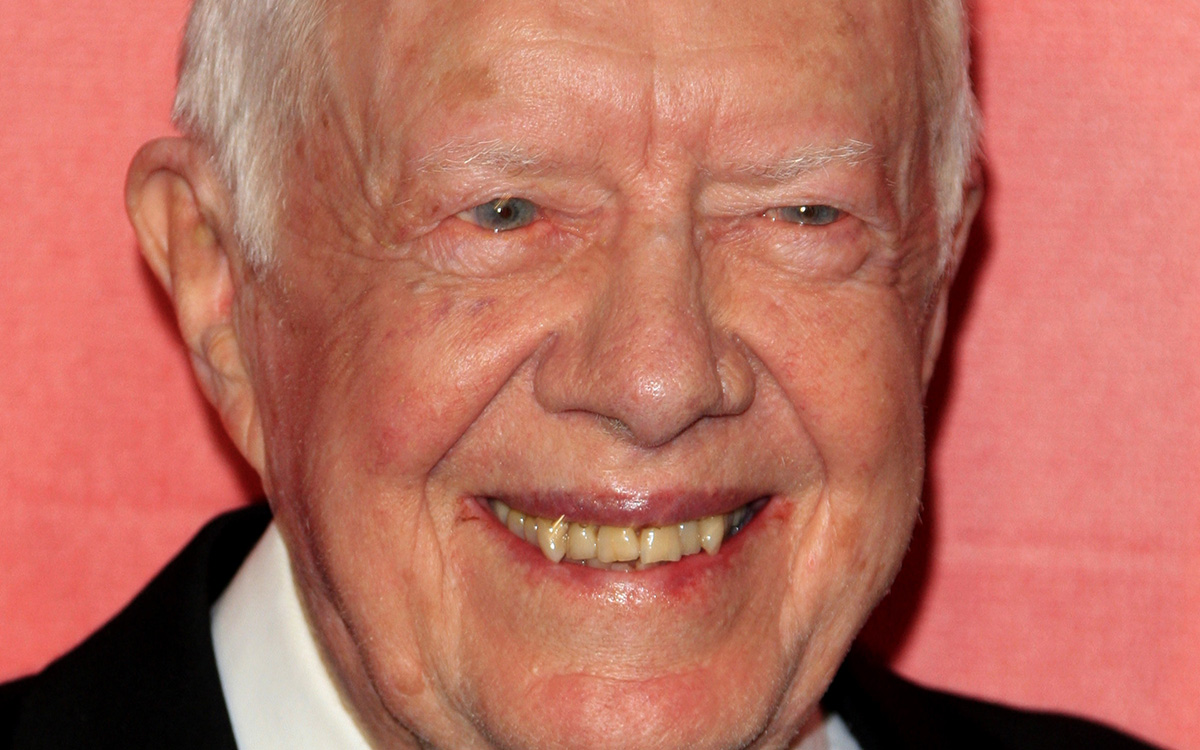

Jimmy Carter, beloved humanitarian and human rights advocate, was supporter of LGBTQ rights

Historic, first-ever meeting with gay activists held at Carter White House in 1977

Former President Jimmy Carter, who died Sunday at the age of 100, is being remembered by both admirers and political observers as a progressive southern Democrat and former Georgia governor who pushed for an end to racial injustice in the U.S., and as a beloved humanitarian who worked hard as president and during his post-presidential years to improve the lives of people in need throughout the world.

Carter’s death comes over a year after the passing on Nov. 19, 2023, of former First Lady Rosalynn Carter, his wife and devoted partner of 77 years. Carter also had the distinction of becoming the oldest living former U.S. president after the death at the age of 94 of former President George H.W. Bush on Nov. 30, 2018.

The former president’s passing also follows his decision in February 2023 to receive hospice care at his family home in Plains, Ga., at the age of 98 after declining additional medical intervention to continue treatment of several ailments that required hospitalization over the previous several months.

Modest beginnings

Jimmy Carter was born Oct. 1, 1924, at a hospital in his hometown of Plains, Ga., where he was raised on his parents’ peanut farm. His decades of public service took place after he graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1946 and he began his service as a submariner.

He left the Navy after the death of his father in 1953, taking over the Carter family business in what was then a segregated Georgia with strong lines between Blacks and Whites. He was an early supporter of the nascent civil rights movement and became an activist within the Democratic Party and a leading voice for the change needed to end racial segregation.

Carter was first elected to public office in 1963 as a state senator, for which he served until 1967. He successfully ran for governor in 1970 and served as Georgia governor until 1975, when he turned his attention to a possible run for U.S. president as a progressive southern Democrat.

Many political observers have said although he was relatively unknown outside of Georgia and within the leadership of the Democratic Party, Carter was able to parlay voter fatigue and the public’s response to the Nixon Watergate scandal and the growing opposition to the Vietnam War to establish himself as an outsider candidate removed from scandal and bad policies.

Appearing to answer the nation’s needs at that time, Carter’s slogan at the start of his presidential campaign was, “A Leader, For A Change.” He came out ahead of nine other Democrats, most of them better known than him, to win the 1976 Democratic nomination for president.

The thirty-ninth President of the United States, Carter served from 1977 to 1981 at a time when support for LGBTQ people was in its early stages, with many elected officials remaining cautious about the potential political risk for outwardly embracing “gay rights.”

Yet during his 1976 presidential campaign, Carter surprised some political observers when he stated at a press conference during a campaign trip to San Francisco in May of that year that he would sign the Equality Act, the gay civil rights bill introduced by then U.S. Rep. Bella Abzug (D-N.Y.) if it reached his desk as president.

“I will certainly sign it, because I don’t think it’s right to single out homosexuals for abuse or special harassment,” he said.

While Carter did not back away from that statement, gay activists were disappointed at the time of the Democratic National Convention in New York City in July 1976, when they said convention officials at the request of the Carter campaign refused to include a gay rights plank as part of the Democratic Party’s platform approved at the convention.

Some LGBT Democratic activists attending the convention said they agreed with the contention of Carter supporters that Carter should not be hampered by a controversial issue that could hurt his chances of defeating Republican President Gerald Ford in the November 1976 presidential election.

Carter narrowly defeated Ford in the election. Some political observers said Ford might have won except for the negative fallout from his decision to pardon former President Richard Nixon, who resigned from office in the midst of the Watergate scandal and allegations that Nixon engaged in illegal activity by playing some role in the break-in at the Democratic Party headquarters in D.C.’s Watergate office building that triggered the scandal.

In March of 1977, just over two months after Carter was inaugurated as president, the White House hosted an historic, first-of-its-kind meeting with fourteen prominent gay rights leaders from throughout the country. Carter did not attend the meeting and was staying at the presidential retreat at Camp David, Md., at the time of the meeting, which was organized by presidential assistant for public liaison Margaret “Midge” Costanza. But White House officials said Carter was aware of the meeting and supported efforts by Costanza and other White House staffers to interact with the gay leaders.

“The meeting was a happy milestone on the road to full equality under the law for gay women and men, and we are highly optimistic that it will soon lead to complete fulfilment of President Carter’s pledge to end all forms of Federal discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation,” said Jean O’Leary, then co-executive director of the National Gay Task Force, which helped select the gay activists who attended the meeting. Among those attending was D.C. pioneer gay rights advocate Frank Kameny.

But about one year later in 1978, some LGBT leaders joined famed gay San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk in criticizing Carter for being slow to speak out against California’s Proposition 6, also known as the Briggs Initiative, a ballot measure asking voters to approve a law to ban gay and lesbian individuals from working in California public schools as teachers or staff members.

In a June 28, 1978, letter to Carter, Milk called on the president to take a stand against Proposition 6 and speak out more forcefully in support of LGBT rights. “As the President of a nation which includes 15-20 million lesbians and gay men, your leadership is vital and necessary,” Milk wrote.

About four months later, in a Nov. 4, 1978, campaign speech in support of California Democratic candidates in Sacramento, three days before the Nov. 7 election, Carter spoke out against Proposition 6 and urged voters to defeat it. Others who spoke out against it earlier were former President Ford and then former California GOP Governor Ronald Reagan as well as California’s then Democratic Governor Edmund Jerry Brown.

Voters defeated the proposition by a margin of 58.4 percent to 41.5 percent, with opponents of the anti-gay measure thanking Carter for speaking out against it.

During his presidency Carter helped put in place two new federal cabinet-level agencies – the Department of Energy and the Department of Education. One of the highlights of his presidential years was his role in bringing about the historic Camp David Accords, the peace agreements between Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat.

The initial agreement, signed in September 1978, which led to the first-ever peace treaty between Israel and Egypt one year later in 1979, came about after Carter invited the two Middle East leaders to meet together with him and to begin negotiations at the U.S. presidential retreat at Camp David, Md. Sadat and Begin were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1978 for their contributions to the historic agreements that were brokered by President Carter.

Despite this and other important achievements, Carter faced multiple setbacks the following year in 1979 related to international developments that political observers say Carter and his advisors failed to address properly. Among them was the revolution in Iran that toppled the reign of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and installed the fundamentalist Islamic regime headed by Ayatollah Khomeini that led to a dramatic drop in Iran’s production and sale of oil. That quickly led to a dramatic rise in the cost of gasoline for American consumers along with a shortage of gas at fuel pumps leading to long lines as filling stations.

If that were not enough, Carter was hit with the take-over of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on Nov. 4, 1979, by militant Iranian youths supported and encouraged by Khomeini who held as hostages 52 U.S. diplomats and American citizens with no sign that they would be released any time soon. As Carter’s poll ratings declined, then U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.) announced his candidacy for the 1980 Democratic presidential nomination in a rare challenge to an incumbent president.

With all that as a backdrop, gay Democratic activists launched a campaign to elect far more openly gay and lesbian delegates to the 1980 Democratic National Convention than they had in 1976. A record number of just over 100 gay and lesbian delegates emerged from this effort, with many of them pledged to Kennedy. And this time around, the Democratic Party leaders backing Carter at the convention, as well as Carter himself, according to some reports, expressed support for including a “gay” plank in the party’s platform, which the convention adopted in an historic first.

But when it became clear that Kennedy and California Governor Jerry Brown, who also challenged Carter for the 1980 Democratic nomination, did not have enough delegates to wrest the nomination from Carter, gay activists expressed concern that the Carter campaign was backing away from taking a stronger position in support of gay rights.

Their main concern was that the response by the Carter campaign to a “gay” questionnaire the National Gay Task Force sent to all the Democratic and Republican presidential candidates seeking their party’s nomination in 1980 was significantly less specific than the response by Kennedy and Brown.

Among other things, the activists said the Carter campaign’s response, which was prepared by Carter Campaign Chairperson Robert Strauss, did not make a commitment for Carter to sign an executive order ending the longstanding discrimination against gays and lesbians in federal government agencies, including the military. The Carter campaign response also did not express support for the national gay rights bill, even though Carter had expressed support for it back in 1976.

Carter supporters, including many in the then gay and lesbian community, pointed out that Straus’s response to the questionnaire expressed overall support for the rights of the gay and lesbian community and a commitment to follow up on that support over the next four years. Gay Carter supporters also pointed out that Carter would be far more supportive than Ronald Regan, who had captured the 1980 Republican presidential nomination.

Some historians have said that the final straw in dooming Carter’s chances for a second term, in addition to his seeming inability to gain the release of the American hostages held in Iran, was the final televised debate between Carter and Reagan. With most political observers saying Reagan was an infinitely superior television candidate, those observations appeared to be confirmed when Carter’s poll numbers dropped significantly following the final debate.

Although Reagan captured 51.8 percent of the popular vote, with Carter receiving 41.0 percent and independent candidate John Anderson receiving 6.6 percent, Reagan won an Electoral College landslide, with 489 electoral votes compared to 49 for Carter. Reagon won in 44 states, with Carter winning in just 6 states and the District of Columbia.

Carter Center and post-presidential career

Both Carter supporters as well as critics and independent political observers agree that Jimmy Carter’s years after leaving the White House have been filled with years of work dedicated to his passion for the advancement of human rights, peace negotiations, advancing worldwide democracy, and advancing disease prevention and eradication in developing nations.

Most of that work was accomplished through The Carter Center, an Atlanta based nonprofit organization that Carter and wife Rosalynn founded in 1982. Twenty years after its founding, Jimmy Carter was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002. The Nobel Committee, among other things, stated it selected Carter for the Nobel Peace Prize “for his decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development.”

In the years following his presidency Carter also continued to lend support as an ally to the LGBTQ community. During a book tour promoting his book, “A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety,” Carter stated in a July 2018 interview with Huff Post Live, that he supported same-sex marriage.

As a long-time self-described born-again Christian, Carter said in the interview, “I think Jesus would approve gay marriage,” adding, “I think Jesus would encourage any love affair if it was honest and sincere and was not damaging to anyone else, and I don’t see that gay marriage damages anyone else.”

His expression of support for same-sex marriage came four years after he responded to a question about his thoughts about LGBTQ rights and religion during an appearance at Michigan’s Grand Rapids Community College in 2014.

“I never knew of any word or action of Jesus Christ that discriminated against anyone,” he said. “Discrimination against anyone and depriving them of actual equal rights in the United States is a violation of the basic principles of the Constitution that all of us revere in this country,” Carter stated at the event.

Federal Government

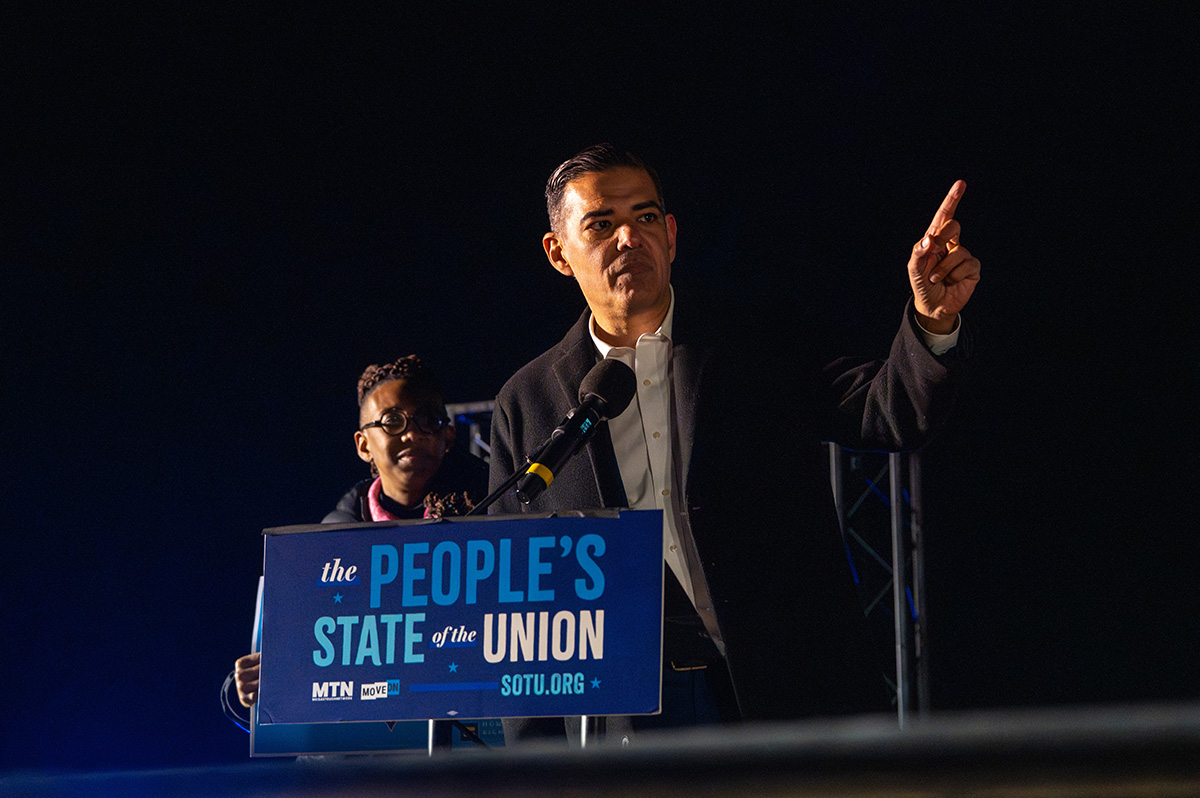

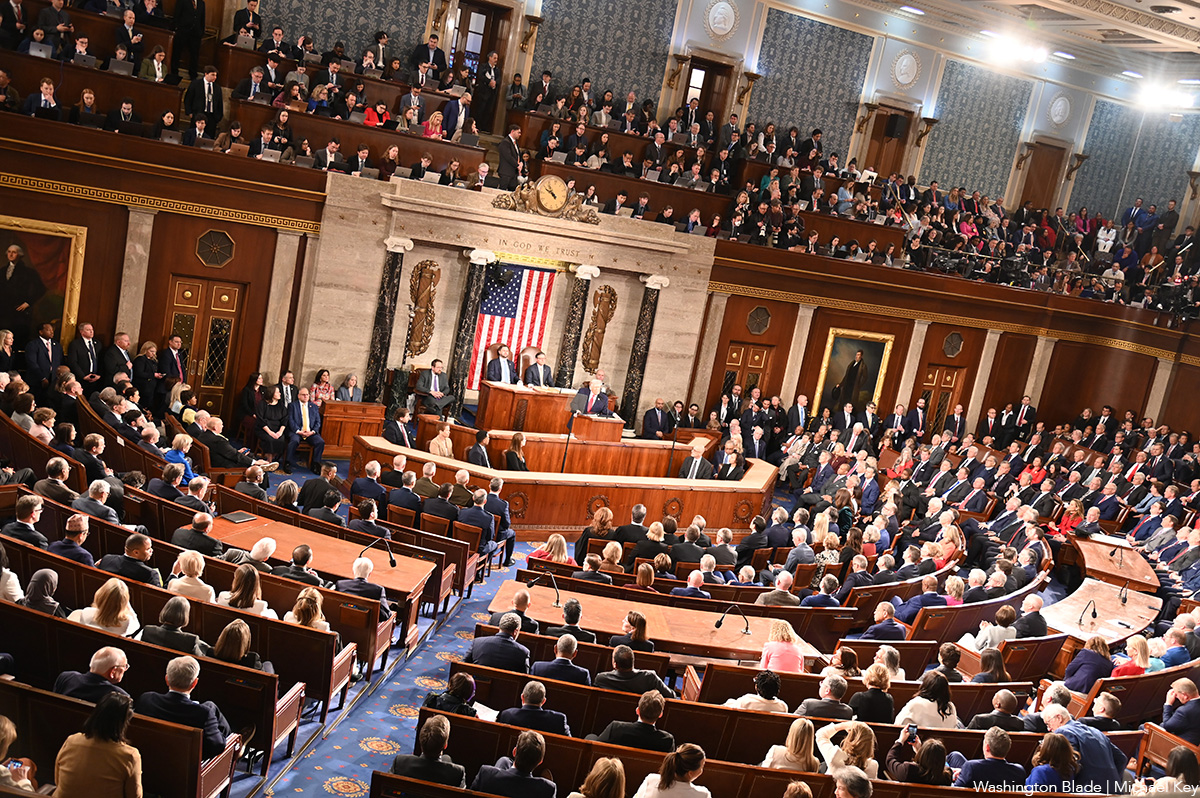

Two very different views of the State of the Union

As Trump delivered his SOTU address inside the Capitol, Democratic lawmakers gathered outside in protest, condemning the administration’s harmful policies.

As President Donald Trump delivered his State of the Union address inside the U.S. Capitol — touting his achievements and targeting political enemies — progressive members of Congress gathered just outside in protest.

Their message was blunt: For many Americans, particularly LGBTQ people, the country is not better off.

Each year, as required by Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution, the president must “give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union.” The annual address is meant to outline accomplishments and preview the year ahead. This year, Trump delivered the longest State of the Union in U.S. history, clocking in at one hour and 48 minutes. He spoke about immigration, his “law and order” domestic agenda, his “peace through strength” foreign policy doctrine, and what he framed as the left’s ‘culture wars’ — especially those involving transgender youth and Christian values.

But one year into what he has called the “Trump 2.0” era, the picture painted outside the Capitol stood in stark contrast to the one described inside.

Transgender youth

In one of the most pointed moments of his speech, Trump spotlighted Sage Blair, using her story to portray gender-affirming care as coercive and dangerous. Framing the issue as one of parental rights and government overreach, he told lawmakers and viewers:

“In the gallery tonight are Sage Blair and her mother, Michelle. In 2021, Sage was 14 when school officials in Virginia sought to socially transition her to a new gender, treating her as a boy and hiding it from her parents. Hard to believe, isn’t it? Before long, a confused Sage ran away from home.

“After she was found in a horrific situation in Maryland, a left-wing judge refused to return Sage to her parents because they did not immediately state that their daughter was their son. Sage was thrown into an all-boys state home and suffered terribly for a long time. But today, all of that is behind them because Sage is a proud and wonderful young woman with a full ride scholarship to Liberty University.

“Sage and Michelle, please stand up. And thank you for your great bravery and who can believe that we’re even speaking about things like this. Fifteen years ago, if somebody was up here and said that, they’d say, what’s wrong with him? But now we have to say it because it’s going on all over, numerous states, without even telling the parents.

“But surely, we can all agree no state can be allowed to rip children from their parents’ arms and transition them to a new gender against the parents’ will. Who would believe that we’ve been talking about that? We must ban it and we must ban it immediately. Look, nobody stands up. These people are crazy. I’m telling you, they’re crazy.”

The story, presented as encapsulation of a national crisis, became the foundation for Trump’s renewed call to ban gender-affirming care. LGBTQ advocates — and those familiar with Blair’s story — argue that the situation was far more complex than described and that using a single anecdote to justify sweeping federal restrictions places transgender people, particularly youth, at greater risk.

Equality Virginia said the president’s remarks were part of a broader effort to strip transgender Americans of access to care. In a statement to the Blade, the group said:

“Tonight, the president is choosing to double down on efforts to disrupt access to evidence-based, lifesaving care.

“Rather than allowing families and doctors to navigate deeply personal medical decisions free from federal interference — or allowing schools to respond with nuance and compassion without putting marginalized children at risk — the president is instead advocating for reckless, one-size-fits-all political control.

“At a time when Virginians are worried about rising costs, economic uncertainty, and aggressive immigration enforcement actions disrupting communities and families, attacking transgender young people is a blatant political distraction from the real challenges facing our nation. Virginia families and health care providers do not need Donald Trump telling them what care they do or do not need.”

For many in the LGBTQ community, the rhetoric inside the chamber echoed actions already taken by the administration.

Earlier this month, the Pride flag was removed from the Stonewall National Monument under a National Park Service directive that came from the top. Community members returned to the site, raised the flag again, and filed suit, arguing the removal violated federal law. To advocates, the move was symbolic — a signal that even the legacy of LGBTQ resistance was not immune.

Immigration and fear

Immigration dominated both events as well.

Inside the chamber, Trump boasted about the hundreds of thousands of immigrants detained in makeshift facilities. Outside, Democratic lawmakers described those same facilities as concentration camps and detailed what they characterized as the human toll of the administration’s enforcement policies.

Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), speaking to the crowd, painted a grim picture of communities living in fear:

“People are vanishing into thin air. Quiet mornings are punctuated by jarring violence. Students are assaulted by ICE agents sitting outside the high school, hard working residents are torn from their vehicles in front of their children. Families, hopelessly search for signs of their loved ones who have stopped answering their phones, stop replying to text… This is un-American, it is illegal, it is unconstitutional, and the people are going to rise up and fight for Gladys Vega and all of those poor people who today need to know that the people’s State of the Union is the beginning of a long fight that is going to result in the end of Republican control of the House of Representatives and the Senate in the United States of America in 2026.”

Speakers emphasized that LGBTQ immigrants are often especially vulnerable — fleeing persecution abroad only to face detention and uncertainty in the United States. For them, the immigration crackdown and the attacks on transgender health care are not separate battles but intertwined fronts in a broader cultural and political war.

Queer leadership

After delivering remarks alongside Robert Garcia, Kelley Robinson, president of the Human Rights Campaign, took the stage and transformed the freezing crowd’s anger into resolve.

Garcia later told the Blade that visibility matters in moments like this — especially when LGBTQ rights are under direct attack.

“We should be crystal clear about right now what is happening in our country,” Garcia said. “We have a president who is leading the single largest government cover up in modern history, we have the single largest sex trafficking ring in modern history right now being covered up by Donald Trump and Pam Bondi In the Department of Justice. Why are we protecting powerful, wealthy men who have abused and raped women and children in this country? Why is our government protecting these men at this very moment? In my place at the Capitol is a woman named Annie farmer. Annie and her sister Maria, both endured horrific abuse by Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell. As we move forward in this investigation, always center the survivors; we are going to get justice for the survivors. And Donald Trump may call this investigation a hoax. He may try to deflect our work, but our message to him is very clear that our investigation is just getting started, and we will we will get justice for these survivors.”

He told the Blade afterwards that having queer leaders front and center is itself an act of resistance.

“I obviously was very honored to speak with Kelley,” the California representative said. Kelley is doing a great job…it’s important that there are queer voices, trans voices, gay voices, in protest, and I think she’s a great example of that. It’s important to remind the country that the rights of our community continue to be attacked, and then we’ve got to stand up. Got to stand up for this as well.”

Robinson echoed that call, urging LGBTQ Americans — especially young people — not to lose hope despite the administration’s escalating rhetoric.

“There are hundreds of thousands of people that are standing up for you every single day that will not relent and will not give an inch until every member of our community is protected, especially our kids, especially our trans and queer kids. I just hope that the power of millions of voices drowns out that one loud one, because that’s really what I want folks to see at HRC. We’ve got 3.6 million members that are mobilizing to support our community every single day, 75 million equality voters, people that decide who they’re going to vote for based on issues related to our community. Our job is to make sure that all those people stand up so that those kids can see us and hear our voices, because we’re going to be what stands in the way.”

A boycott — and a warning

The list of Democratic lawmakers who boycotted the State of the Union included Sens. Ruben Gallego, Ed Markey, Jeff Merkley, Chris Murphy, Adam Schiff, Tina Smith, and Chris Van Hollen, along with dozens of House members.

For those gathered outside — and for viewers watching the livestream hosted by MoveOn — the counter-programming was not merely symbolic. It was a warning.

While the president spoke of strength and success inside the chamber, LGBTQ Americans — particularly transgender youth — were once again cast as political targets. And outside the Capitol, lawmakers and advocates made clear that the fight over their rights is far from over.

U.S. Military/Pentagon

4th Circuit rules against discharged service members with HIV

Judges overturned lower court ruling

A federal appeals court on Wednesday reversed a lower court ruling that struck down the Pentagon’s ban on people with HIV enlisting in the military.

The conservative three-judge panel on the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned a 2024 ruling that had declared the Defense Department and Army policies barring all people living with HIV from military service unconstitutional.

The 4th Circuit, which covers Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia, held that the military has a “rational basis” for maintaining medical standards that categorically exclude people living with HIV from enlisting, even those with undetectable viral loads — meaning their viral levels are so low that they cannot transmit the virus and can perform all duties without health limitations.

This decision could have implications for other federal circuits dealing with HIV discrimination cases, as well as for nationwide military policy.

The case, Wilkins v. Hegseth, was filed in November 2022 by Lambda Legal and other HIV advocacy groups on behalf of three individual plaintiffs who could not enlist or re-enlist based on their HIV status, as well as the organizational plaintiff Minority Veterans of America.

The plaintiffs include a transgender woman who was honorably discharged from the Army for being HIV-positive, a gay man who was in the Georgia National Guard but cannot join the Army, and a cisgender woman who cannot enlist in the Army because she has HIV, along with the advocacy organization Minority Veterans of America.

Isaiah Wilkins, the gay man, was separated from the Army Reserves and disenrolled from the U.S. Military Academy Preparatory School after testing positive for HIV. His legal counsel argued that the military’s policy violates his equal protection rights under the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

In August 2024, a U.S. District Court sided with Wilkins, forcing the military to remove the policy barring all people living with HIV from joining the U.S. Armed Services. The court cited that this policy — and ones like it that discriminate based on HIV status — are “irrational, arbitrary, and capricious” and “contribute to the ongoing stigma surrounding HIV-positive individuals while actively hampering the military’s own recruitment goals.”

The Pentagon appealed the decision, seeking to reinstate the ban, and succeeded with Wednesday’s court ruling.

Judge Paul V. Niemeyer, one of the three-judge panel nominated to the 4th Circuit by President George H. W. Bush, wrote in his judicial opinion that the military is “a specialized society separate from civilian society,” and that the military’s “professional judgments in this case [are] reasonably related to its military mission,” and thus “we conclude that the plaintiffs’ claims fail as a matter of law.”

“We are deeply disappointed that the 4th Circuit has chosen to uphold discrimination over medical reality,” said Gregory Nevins, senior counsel and employment fairness project director for Lambda Legal. “Modern science has unequivocally shown that HIV is a chronic, treatable condition. People with undetectable viral loads can deploy anywhere, perform all duties without limitation, and pose no transmission risk to others. This ruling ignores decades of medical advancement and the proven ability of people living with HIV to serve with distinction.”

“As both the 4th Circuit and the district court previously held, deference to the military does not extend to irrational decision-making,” said Scott Schoettes, who argued the case on appeal. “Today, servicemembers living with HIV are performing all kinds of roles in the military and are fully deployable into combat. Denying others the opportunity to join their ranks is just as irrational as the military’s former policy.”

New York

Lawsuit to restore Stonewall Pride flag filed

Lambda Legal, Washington Litigation Group brought case in federal court

Lambda Legal and Washington Litigation Group filed a lawsuit on Tuesday, challenging the Trump-Vance administration’s removal of the Pride flag from the Stonewall National Monument in New York earlier this month.

The suit, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, asks the court to rule the removal of the Pride flag at the Stonewall National Monument is unconstitutional under the Administrative Procedures Act — and demands it be restored.

The National Park Service issued a memorandum on Jan. 21 restricting the flags that are allowed to fly at National Parks. The directive was signed by Trump-appointed National Park Service Acting Director Jessica Bowron.

“Current Department of the Interior policy provides that the National Park Service may only fly the U.S. flag, Department of the Interior flags, and the Prisoner of War/Missing in Action flag on flagpoles and public display points,” the letter from the National Park Service reads. “The policy allows limited exceptions, permitting non-agency flags when they serve an official purpose.”

That “official purpose” is the grounds on which Lambda Legal and the Washington Litigation Group are hoping a judge will agree with them — that the Pride flag at the Stonewall National Monument, the birthplace of LGBTQ rights movement in the U.S., is justified to fly there.

The plaintiffs include the Gilbert Baker Foundation, Charles Beal, Village Preservation, and Equality New York.

The defendants include Interior Secretary Doug Burgum; Bowron; and Amy Sebring, the Superintendent of Manhattan Sites for the National Park Service.

“The government’s decision is deeply disturbing and is just the latest example of the Trump administration targeting the LGBTQ+ community. The Park Service’s policies permit flying flags that provide historical context at monuments,” said Alexander Kristofcak, a lawyer with the Washington Litigation Group, which is lead counsel for plaintiffs. “That is precisely what the Pride flag does. It provides important context for a monument that honors a watershed moment in LGBTQ+ history. At best, the government misread its regulations. At worst, the government singled out the LGBTQ+ community. Either way, its actions are unlawful.”

“Stonewall is the birthplace of the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement,” said Beal, the president of the Gilbert Baker Foundation. The foundation’s mission is to protect and extend the legacy of Gilbert Baker, the creator of the Pride flag.

“The Pride flag is recognized globally as a symbol of hope and liberation for the LGBTQ+ community, whose efforts and resistance define this monument. Removing it would, in fact, erase its history and the voices Stonewall honors,” Beal added.

The APA was first enacted in 1946 following President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s creation of multiple new government agencies under the New Deal. As these agencies began to find their footing, Congress grew increasingly worried that the expanding powers these autonomous federal agencies possessed might grow too large without regulation.

The 79th Congress passed legislation to minimize the scope of these new agencies — and to give them guardrails for their work. In the APA, there are four outlined goals: 1) to require agencies to keep the public informed of their organization, procedures, and rules; 2) to provide for public participation in the rule-making process, for instance through public commenting; 3) to establish uniform standards for the conduct of formal rule-making and adjudication; and 4) to define the scope of judicial review.

In layman’s terms, the APA was designed “to avoid dictatorship and central planning,” as George Shepherd wrote in the Northwestern Law Review in 1996, explaining its function.

Lambda Legal and the Washington Litigation Group are arguing that not only is the flag justified to fly at the Stonewall National Monument, making the directive obsolete, but also that the National Park Service violated the APA by bypassing the second element outlined in the law.

“The Pride flag at the Stonewall National Monument honors the history of the fight for LGBTQ+ liberation. It is an integral part of the story this site was created to tell,” said Lambda Legal Chief Legal Advocacy Officer Douglas F. Curtis in a statement. “Its removal continues the Trump administration’s disregard for what the law actually requires in their endless campaign to target our community for erasure and we will not let it stand.”

The Washington Blade reached out to the NPS for comment, and received no response.