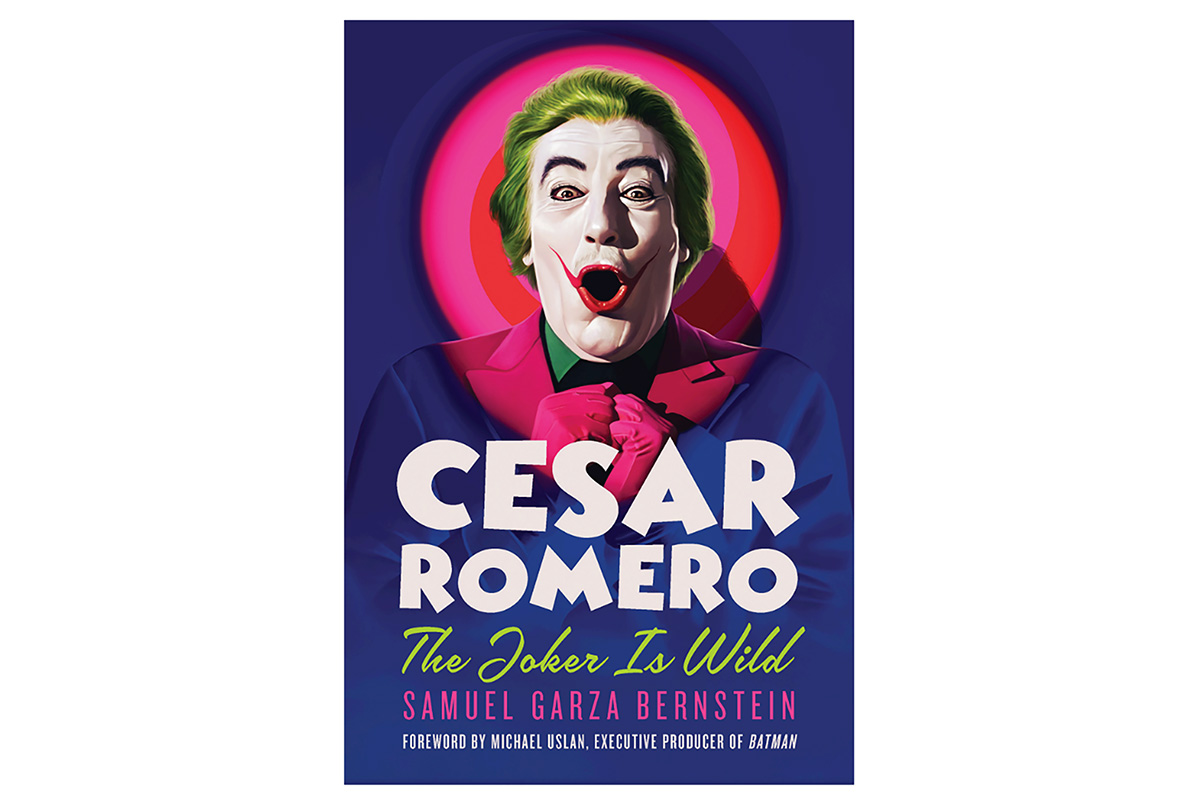

Commentary

The Joker as queer icon

Cesar Romero’s camp performance is part of my gay coming of age

That Cesar Romero was a gay man is not a revelation at this point—scandalous or otherwise. During his years as a studio contract star in the 1930s to the early 1950s, he participated in the dream machine fantasy of dating eligible Hollywood actresses, but looking back at his fan magazine coverage today, it never seems forced or false. He and Joan Crawford laugh uproariously in each other’s arms; he shares a cigarette with Ann Sheridan with a gleeful, conspiratorial gleam in his eye; he winks at Betty Furness with a clear sense of intimacy.

He’s clearly having a blast. Romero is lucky that something he is genuinely passionate about—dancing and nightclubbing—makes him appear as something of a hetero wolf to movie fans. He doesn’t have to pretend as much as other gay stars. Tall, masculine, and graceful, he satisfies the dictates of the era in terms of what being a man is all about. That his ironic nickname is “Butch” is never given much scrutiny. So how does this hunk become a gay icon?

Of course, as far as I’m concerned, dancing with Carmen Miranda is enough to qualify. Miranda dances with many others in her fruity Technicolor fantasies—Wallace Beery, Steve Cochran, Groucho Marx, Dean Martin—but no one else matches her energy level and attitude the way Romero does in “Week-End in Havana” and “Springtime in the Rockies,”though in the latter it’s a group number. Miranda is part of his legacy in other ways. There’s also a censored Fox publicity photo where he is hoisting her in a lift that reveals Carmen is no fan of a Brazilian wax. And a woman in California identifies as the daughter of Carmen and Cesar, though without DNA analysis, the claim is impossible to prove or disprove. For the record, she acknowledges Cesar’s sexuality—just claims that Carmen brought out his fluidity. And if a gay man is going to sleep with a woman, it does seem appropriate that the woman in question would be Carmen Miranda.

Cesar Romero is in the business almost 40 years before “Batman”comes along in 1966. In those years he goes from Broadway dancer to Latin lover, from Shirley Temple’s “exotic” kidnapper to the Cisco Kid, from sociopathic gangster to perennial variety show guest star. Always a leading man. Always a romantic possibility. He is almost 60 when he plays the Joker for the first time. His full-bodied, hammy, joyful performance vaults him into pop cultural superstardom. He’s on lunch boxes, school supplies, board games, T-shirts, jigsaw puzzles, and trading cards; he becomes an action figure and a Halloween mask; toys inspired by him include joy buzzers, squirting flowers, and trick guns; and the character goes from being one of many Batmanvillains to rivaling the popularity of the Caped Crusaders themselves.

I believe that letting go of the masculine myth of leading man stardom is really what makes the Joker possible. It’s what lets Romero cut loose so wildly. There are usually a few buxom girls hanging around his lair, but Adam West gets his full attention. It isn’t until the late 1970s, when “Batman”is in afternoon reruns, that I see Romero as the Joker for the first time. I fall in love immediately, and it is the camp element that attracts. This is not just my introduction to the Joker and Romero; it is my first real exposure to live-action superheroes of any kind, leaving me with a sense of the genre being great fun and, more important, as a place that is queer friendly, though I don’t have the vocabulary or sense of cultural identity to articulate it in that way at the time. The only other nascent LGBTQIA+ representation in the media I remember from that era is also camp—with the usual suspects—performers like Charles Nelson Reilly, Paul Lynde, Rip Taylor, and Wayland Flowers and Madame (a phenomenally popular ventriloquist and his garrulous drag queen-like puppet). More serious fare, like “That Certain Summer”and “Boys in the Band,” is not in my childhood experience, and the idea of lesbians, bisexuals, and trans people is not yet on my radar.

I recognize these men as projections of my future self. While I don’t imagine myself growing up and plotting the demise of grown men who wear their underpants outside of their tights, I recognize the humor, the mannerisms, and the undercurrents if not the physicality of the innuendos. And Cesar Romero takes no shit. By the end of the first of each two-episode story, he’s always winning. I know he will lose by the end of the second part, but on some level, I recognize that as a fulfillment of the narrative demands of the form rather than as a personal loss for him. To me, he is a winner, and I like that very much. I’m an effeminate kid, thankfully not bullied or particularly singled out, but for a variety of reasons, I don’t feel very powerful. The Joker’s wild abandon is inspiring and empowering in a cockeyed sort of way. It has nothing to do with conforming to anyone’s idea of being masculine, and it has everything to do with proudly letting your freak flag fly.

In 1989, when “Batman”gets its historic reboot, the menace of Jack Nicholson is startlingly different from Cesar Romero. By the time of the Oscar-winning performances of Heath Ledger and Joaquin Phoenix, as well as Jared Leto, where the Joker becomes a truly frightening psychopath, Nicholson comes to seem relatively lighthearted, closer to Romero than to Ledger or Phoenix. The camp is mostly gone, but not the queerness. An underlying gender fluidity still informs the Joker through all of the live-action performances, and the character’s erotic obsession with Batman has deepened. With Romero it never had a truly carnal edge. By the time we hit Ledger, Phoenix, and Leto—the character appears entirely pansexual—frankly it’s the most recognizably human part of him that remains in his current incarnation. My original notion of the superhero space being LGBTQIA+ friendly has proven spectacularly accurate—prescient even. Now, Robin, Harley Quinn, Catwoman, and Batwoman are all queer identifying across various media. But Cesar Romero got there first, and for me, his lighthearted, gleeful camp performance will always be a part of my own gay coming of age. Hail Cesar.

Samuel Garza Bernstein is an award-winning author, screenwriter, and playwright. His latest book is ‘Cesar Romero: The Joker Is Wild.’

Commentary

Defunding LGBTQ groups is a warning sign for democracy

Global movement since January 2025 has lost more than $125 million in funding

In over 60 countries, same-sex relations are criminal. In many more, LGBTIQ people are discriminated against, harassed, or even persecuted. Yet, in most parts of the world, if you are an LGBTIQ person, there is an organization quietly working to keep people like you safe: a lawyer fighting an arrest, a shelter offering refuge from violence, a hotline answering a midnight call. Many of those organizations have now lost so much funding that they may be forced to close.

One year ago this week, the U.S. government froze foreign assistance to organizations working on human rights, democracy, and development worldwide. The effects were immediate. For LGBTIQ communities, the impact has been severe and far-reaching.

For 35 years, Outright International has helped build and sustain the global movement for the rights of LGBTIQ people, working with local partners in more than 75 countries. Many of those partners are now facing sudden closure.

Since January 2025, more than $125 million has been stripped from efforts advancing the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer people globally. That figure represents at least 30 percent of yearly international funding for this work. Organizations that ran emergency shelters, legal defense programs, and HIV prevention services have been forced to close or drastically scale back operations. At Outright alone, we lost funding for 120 grants across nearly 50 countries. We estimate that, without intervention, 20 to 25 percent of our grantee partners risk shutting down entirely.

But this is not only a story about one community. It is a story about how authoritarianism works, and what it costs when we fail to recognize the pattern.

The playbook is not subtle

Researchers at Outright and partners across human rights and democracy movements have documented the same sequence playing out across sectors worldwide: governments defund organizations before passing restrictive legislation, eliminating the groups most likely to document abuses before abuses occur.

In December, CIVICUS downgraded its assessment of U.S. civic freedoms from “narrowed” to “obstructed,” citing what it called a “rapid authoritarian shift.” The message was unmistakable: independent organizations that hold power to account are under growing pressure, in the United States and around the world.

And the effects have cascaded globally. When one of the world’s largest funders of democracy support and human rights work withdraws, it doesn’t just leave a funding gap. It sends a signal to authoritarians everywhere: the coast is clear.

The timing is not coincidental. In the super election year of 2024, 85 percent of countries with national elections featured anti-LGBTIQ rhetoric in campaigns. Across the 15 countries we tracked, governments proposed or enacted laws restricting gender-affirming care, rolling back legal gender recognition, and censoring LGBTIQ expression. The defunding often came first. Governments know that if they can starve the movement, there will be no one left to document what comes next.

Why US readers should care

It may be tempting to see this as a distant crisis, especially at a moment when LGBTIQ rights in the United States are under real pressure. But this story is closer to home than it appears. American funding decisions often help determine whether organizations protecting LGBTIQ people abroad can keep their doors open. And when independent organizations are weakened, no matter where they are, the consequences do not stay contained. The same political networks driving anti-LGBTIQ legislation in the United States share strategies and resources with movements abroad. Global repression and domestic rollback are not separate stories. They are the same story, unfolding in different places.

LGBTIQ organizations are often the first target, but never the last

Why target LGBTIQ communities first? Because we are politically easier to isolate. The same playbook — foreign funding restrictions, bureaucratic harassment, banking access denial — is now being deployed against environmental groups, independent media, women’s rights organizations, and election monitors. When one part of our community is silenced, all of us become more vulnerable. What happens to us is a preview of what happens to everyone.

This is not speculation. It is documented history. In Hungary, the government restricted foreign funding for civil society before passing its “anti-LGBTQ propaganda” law. In Russia, “foreign agent” designations preceded the criminalization of LGBTIQ identity. In Uganda, funding restrictions on human rights organizations came before the Anti-Homosexuality Act. The pattern repeats because it works.

And yet, even as these attacks intensify, victories continue. In 2025, Saint Lucia struck down a colonial-era law criminalizing consensual same-sex intimacy after a decade of regional planning and coalition-building. Courts in India, Japan, and Hong Kong upheld trans people’s rights. Budapest Pride became the largest in Hungarian history — and one of the country’s biggest public demonstrations — despite a government ban. In Thailand, years of patient advocacy culminated in marriage equality becoming law in 2025, the first such victory in Southeast Asia.

These wins happened because our movement built the capacity to survive hostility. Legal defense funds. Documented evidence. Regional coalitions. Emergency response networks. The organizations behind these victories are precisely the ones now facing drastic funding cuts and even closure.

What we are doing and what we need

On Jan. 20, 2026, Outright International publicly launched Funding Our Freedom, a $10 million emergency campaign running through June 30, 2026. We have already secured over $5 million in pledges from more than 150 donors. But the gap remains enormous.

The campaign supports two priorities that must move together. Half of the funds go directly to frontline LGBTIQ organizations facing sudden shortfalls: keeping staff paid, maintaining safe spaces, securing legal support, and continuing essential services. The other half supports Outright’s global work: documenting abuses, training activists, and advocating for LGBTIQ inclusion at the United Nations and other international forums. This is how LGBTIQ people remain seen, heard, and defended, even when governments attempt to erase them.

We structured Funding Our Freedom this way because frontline support without protection is fragile, and global advocacy without frontline truth is hollow. Both must survive.

Funding Our Freedom is not charity. It is how we keep the global LGBTIQ movement alive when governments try to erase it.

A call to those who believe in equality and democracy

If you are part of the LGBTIQ community, this moment is personal. Whether you give, share this work, host a small fundraiser, or bring others into the effort, you become part of what keeps our global community connected and protected.

If you are an ally or simply someone who believes in fairness, free expression, and accountable government, this fight is yours too. The defunding of LGBTIQ organizations is not an isolated decision. It is a test case. If it succeeds, the same tactics will be used against every group that challenges power and defends vulnerable people.

We are not asking for sympathy. We are asking for commitment. The organizations now being forced to close are the ones that document abuses, provide legal defense, support people in crisis, and show up when no one else will. If they disappear, we lose more than services. We lose the ability to know what is happening and to respond.

Authoritarians understand this. That is why they target us first.

The question is whether the rest of us understand it in time.

Maria Sjödin is the executive director of Outright International, where they has worked for over two decades advocating for LGBTIQ human rights worldwide. Learn more at outrightinternational.org/funding-our-freedom.

January arrives with optimism. New year energy. Fresh possibilities. A belief that this could finally be the year things change. And every January, I watch people respond to that optimism the same way. By adding.

More workouts. More structure. More goals. More commitments. More pressure to transform. We add healthier meals. We add more family time. We add more career focus. We add more boundaries. We add more growth. Somewhere along the way, transformation becomes a list instead of a direction.

But what no one talks about enough is this: You can only receive what you actually have space for. You don’t have unlimited energy. You have 100 percent. That’s it. Not 120. Not 200. Not grind harder and magically find more.

Your body knows this even if your calendar ignores it. Your nervous system knows it even if your ambition doesn’t want to admit it. When you try to pour more into a cup that’s already full, something spills. Usually it’s your peace. Or your consistency. Or your health.

What I’ve learned over time is that most people don’t need more motivation. They need clarity. Not more goals, but priority. Not more opportunity, but discernment.

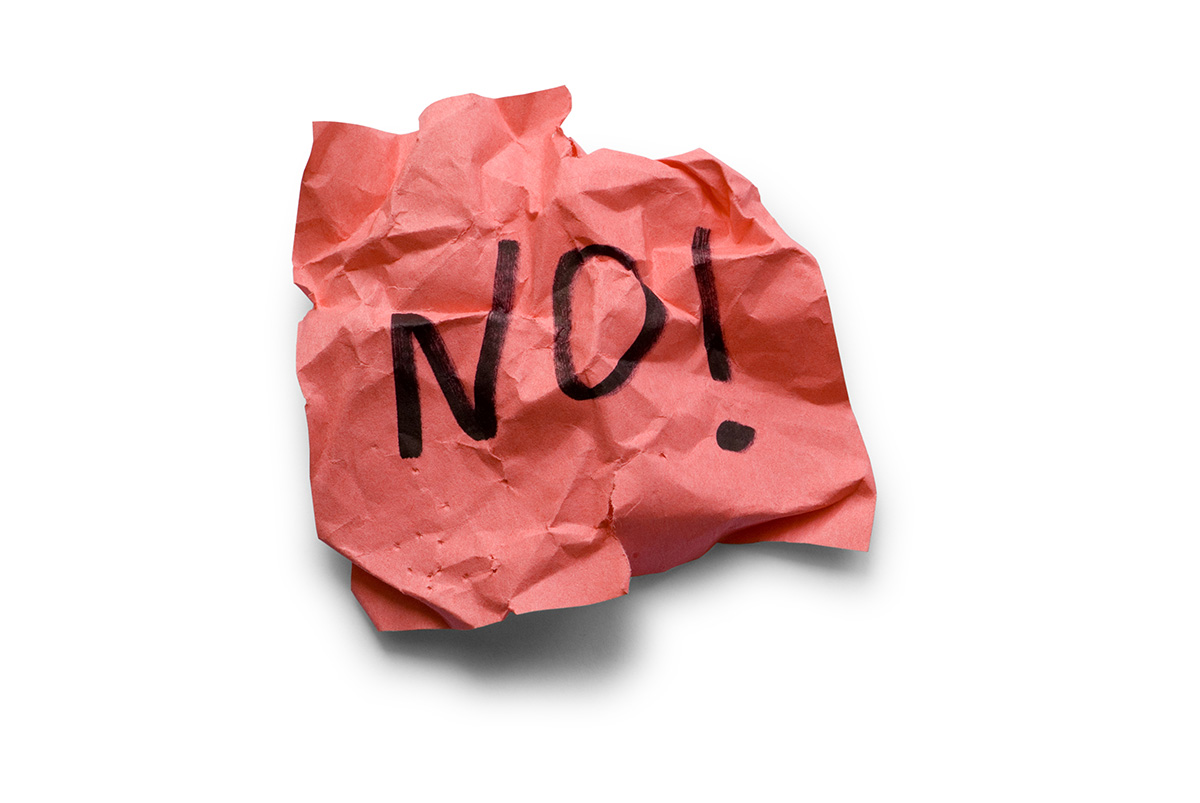

So this January, instead of asking what you’re going to add, I want to offer something different. What if this year becomes a season of no.

No to things that drain you. No to things that distract you. No to things that look good on paper but don’t feel right in your body. And to make this real, here’s how you actually do it.

Identify your one true priority and protect it

Most people struggle with saying no because they haven’t clearly said yes to anything first. When everything matters, nothing actually does. Pick one priority for this season. Not 10. One. Once you identify it, everything else gets filtered through that lens. Does this support my priority, or does it compete with it?

Earlier this year, I had two leases in my hands. One for Shaw and one for National Landing in Virginia. From the outside, the move felt obvious. Growth is celebrated. Expansion is rewarded. More locations look like success. But my gut and my nervous system told me I couldn’t do both.

Saying no felt like failure at first. It felt like I was slowing down when I was supposed to be speeding up. But what I was really doing was choosing alignment over optics.

I knew what I was capable of thriving in. I knew my limits. I knew my personal life mattered. My boyfriend mattered. My family mattered. My physical health mattered. My mental health mattered. Looking back now, saying no was one of the best decisions I could have made for myself and for my team.

If something feels forced, rushed, or misaligned, trust that signal. If it’s meant for you, it will come back when the timing is right.

Look inside before you look outside

So many of us are chasing who we think we’re supposed to be— who the city needs us to be. Who social media rewards. Who our resume says we should become next. But clarity doesn’t come from noise. It comes from stillness. Moments of silence. Moments of gratitude. Moments where your nervous system can settle. Your body already knows who you are long before your ego tries to upgrade you.

One of the most powerful phrases I ever practiced was simple: You are enough.

I said it for years before I believed it. And when I finally did, everything shifted. I stopped chasing growth just to prove something. I stopped adding just to feel worthy. I could maintain. I could breathe. I could be OK where I was.

Gerard from Baltimore was enough. Anything else I added became extra.

Turning 40 made this clearer than ever. My twenties were about finding myself. My thirties were about proving myself. My forties are about being myself.

I wish I knew then what I know now. I hope the 20 year olds catch it early. I hope the 30 year olds don’t wait as long as I did.

Because the only way to truly say yes to yourself is by saying no first.

Remove more than you add

Before you write your resolutions, try this. If you plan to add three things this year, identify six things you’re willing to remove. Habits. Distractions. Commitments. Energy leaks.

Maybe growth doesn’t look like expansion for you this year. Maybe it looks like focus. Maybe it looks like honoring your limits. January isn’t asking you to become superhuman. It’s asking you to become intentional. And sometimes the most powerful word you can say for your future is no.

With love always, Coach G.

Gerard Burley, also known as Coach G, is founder and CEO of Sweat DC.

Commentary

Honoring 50 queer, trans women with inaugural ‘Carrying Change’ awards

Naming the people who carry our movements forward

Dear friends, partners, and community:

We write to you as two proud Black and Brown queer women who have dedicated our lives to building safer, bolder, and more just communities as leaders, organizers, policy advocates, and storytellers.

We are June Crenshaw and Heidi Ellis.

June has spent almost 10 years guiding the Wanda Alston Foundation with deep compassion and unwavering purpose, ensuring LGBTQ+ youth experiencing homelessness have access to stability, safety, and a path forward. Her leadership has expanded housing and support services, strengthened community partnerships, and helped shift how Washington, D.C. understands and responds to the needs of queer and trans young people. In her current role with Capital Pride Alliance, June advances this work at a broader scale by strengthening community infrastructure, refining organizational policies, and expanding inclusive community representation.

Heidi is the founder of HME Consulting & Advocacy, a D.C.–based firm that builds coalitions and advances policy and strategy at the intersection of LGBTQ+ justice and racial equity. Her work spans public service, nonprofit leadership, and strategic consulting to strengthen community-driven solutions.

We’re writing because we believe in intentional recognition — naming the people who carry our movements forward, who make room for those who come next, and who remind us that change is both generational and generative. Too often, these leaders do this work quietly and consistently, without adequate public acknowledgment or what one might call “fanfare,” often in the face of resistance and imposed solitude — whether within their respective spaces or industries.

Today, we are proud to introduce the Torchbearers: “Carrying Change” Awards, an annual celebration honoring 50 unstoppable Queer and Trans Women, and Non-Binary People whose leadership has shaped, and continues to shape, our communities.

This inaugural list will recognize:

- 25 Legends — long-standing leaders whose decades of care, advocacy, and institution-building created the foundations we now stand upon; and

- 25 Illuminators — rising and emerging leaders whose courage, creativity, and innovation are lighting new paths forward.

Why these names matter: Movement memory keeps us honest. Strategy keeps us effective. Recognition keeps us connected. By celebrating both Legends and Illuminators side by side, we are intentionally bridging histories and futures — honoring elders, uplifting survivors, and spotlighting those whose work and brilliance deserve broader support, protection and visibility.

Who will be included: The Torchbearers will represent leaders across a diverse range of sectors, including community organizing, public service, sports, government, entertainment, business, education, legal industry, health, and the arts — reflecting the breadth and depth of queer leadership today. They include organizers providing direct service late into the night; policy experts shaping budgets and laws; artists and culture workers changing hearts and language; healers and mutual-aid leaders; and those doing the quiet, essential work that sustains us all.

Intersectionality is our core commitment: identity in its fullness matters, and honorees must reflect the depth, diversity, and nuance of queer leadership today.

How you can engage: Nominate, amplify, sponsor, and attend. Use your platforms to uplift these leaders, bring your organization’s resources to sustain their work, and help ensure that recognition translates into real support — funding, capacity, visibility, and protection.

We are excited, humbled, and energized to stand alongside the women and non-binary leaders who have carried us, and those who will carry this work forward. If history teaches us anything, it’s that the boldest change happens when we shine light on one another, and then pass the flame.

YOU CAN MAKE A NOMINATION HERE

June Crenshaw serves as deputy director of the Capital Pride Alliance. Heidi Ellis is founder of HME Consulting & Advocacy.