Theater

America’s Bard

Legendary gay playwright Tennessee Williams honored in centennial festival

Tennessee Williams' homosexuality widely informed his work, often in coded ways. (Photo courtesy of the Tennessee Williams Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University)

He is the poet laureate of the American theater.

He pursued young men and boys with sexual voracity, especially hustlers, often rough trade, and those obsessively so in his latter years, but he also delighted greatly in the company of women.

His greatest creations on stage were in fact women, though some argue they were really coded figures who were actually gay males in drag. Certainly most of his heroines — especially perhaps Blanche DuBois in “A Streetcar named Desire” — were extensions of himself, valorous but doomed, haunted by desire, shadowed by failure, driven to despair and sometimes even to madness or to death.

He is Thomas Lanier Williams, born 100 years ago this weekend on Palm Sunday, March 26, 1911, in Columbus, Miss., to Edwina and Cornelius Williams. He was reared in an Episcopal rectory there, where his grandfather, Rev. Walter Dakin, was the local Episcopal priest, and later changed his name to “Tennessee” in honor of that same grandfather, who was born in that state.

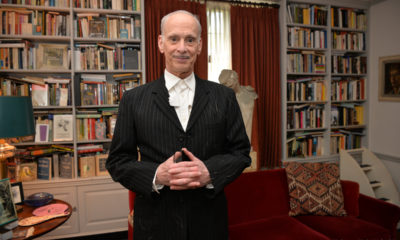

Williams’ sense of sin and salvation in sexuality was central to his inner drives, says Derek Goldman, artistic director of this weekend’s Tennessee Williams Centennial Festival, a raft of plays and staged readings and panel discussions featuring appearances by among others Edward Albee and John Waters (Visit performingarts.georgetown.edu/tenncentfest/festival/ for details). For a long time, Williams was closeted about being gay, though he let it be known to his friends. Goldman says that though Williams had a long-time love relationship with his life partner Frankie Merlo, he was also “very promiscuous, and slept around a lot,” when “his need was for several boys a day at times, and the younger and prettier the better.”

Georgetown University's production of 'Glass Menagerie,' one of Tennessee Williams' most famous works. From left are recent alumni Rachel Caywood and Clark Young with Prof. Sarah Marshall. (Photo by Sue Kessler, courtesy of Georgetown University)

In his writing, however, Goldman says, the thirst to slake his need for for constant sexual consummation, took a different form through sublimation, because in his writing, he “explores not so much the sex but how those desires have a place in society” — or do not. Goldman is also associate professor of theater and performance studies at Georgetown University, where the Williams Festival — known for short as “Tenn Cent Fest” — is housed, and he directs the university’s Davis Performing Arts Center. Goldman says the festival, most of which runs from today through Sunday, has “certainly been a labor of love,” including being able to teach a seminar on Williams work and “for this past year” he says he has been “steeped in all things Williams.”

Goldman’s own first encounter with Williams came on cable TV, however, when he was about 13 and saw the film adaptations of “Streetcar Named Desire” (1951,) and “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” (1958). In each case, of course, Hollywood producers insisted in excisions, and Goldman admits that “I now blush at the fact that they were so sanitized, taking much of the sexuality out.”

For example, Goldman points out that in the original version of “Cat” (which was on Broadway in 1955 when it was directed by Elia Kazan and won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama), it’s clear that Brick (first played by the actor Ben Gazzara) is actually bisexual, or even gay, as he admits to his feelings for his pro football buddy Skipper who has committed suicide. Goldman says that “the back story for Brick is his relationship with Skipper,” and that while Brick’s “sexuality is pretty complicated,” he has certainly “lost interest in Maggie sexually,” and “we understand that he definitely has homosexual desires.”

We, of course, mainly know Williams from his work. That is the only reason he rates such a “Tenn Cent Fest” weekend, more than a quarter century after his death, as Goldman is now curating. But behind and beneath that work was always his beating heart. Reading his private writing shows him “so emotionally naked, as he was working out his own stuff,” Goldman says.

“It shows the undulation between guilt and shame (at being gay), not being accepted for who he really was, and also being able to claim it with pride,” Goldman says. “It was not just one thing. It was a stew of contradictions pulsing back and forth in private.”

In one of Williams’ one-act plays, “Suddenly, Last Summer,” that opened off-Broadway in 1958 as part of a double-bill titled “In The Garden District,” the play is basically two long monologues, considered one of his starkest and most poetic works. Best known from the 1959 film adaptation, it is a mystery melodrama about why Catherine (Elizabeth Taylor in the film) has been institutionalized for severe emotional disturbance, the result of the violent death of her cousin Sebastian by dismemberment and cannibalism by local boys, the objects of his predatory sexual desire, she had witnessed during their trip to Spain. Sebastian’s wealthy mother, Violet Venable (Katharine Hepburn) is determined to hide the exact circumstances of her son’s death and the fact that he was gay.

Maya Roth, Georgetown’s director of theater and performance studies, is directing “Suddenly, Last Summer” at the Davis Performing Arts Center April 7-16. “It is a play about violence against homosexual men,” she says. “It’s about Sebastian,” who is never seen, except at a distance in memory, “and his queerness that can’t be mentioned, the love that dare not speak its name, that’s what ‘Suddenly, Last Summer’ is about.” Though sanitized in the film version, it was written as one of his early plays but for a long time remained unproduced. When it was finally presented on stage, it was a kind of “coming out” for Williams, she says, “and it was really radical, and the reason why Hollywood had to airbrush it out.”

Asked about the legacy of Williams — his many plays as well as novels and short stories and occasional screenplays — Goldman says, “it’s more than a legacy, it’s the urgency still in his work, because it’s still very fresh,” in what he calls its “incredible lyricism and heat, the poetry of its fierce and ferocious imagery, in its language as windows into the soul.”

“He’s the poet of the vulnerable, whose compassion is in the size of his tenderness and faith in the beauty of the broken, those who have suffered the collateral damages of a world that doesn’t celebrate individuality, that doesn’t make allowances for the beauty of the broken,” Goldman says. “He’s the one who pierces the heart and the intellect, but it’s the heart, the emotional connection that we have to his work, that is most indelible.”

“He’s our American Shakespeare,” Goldman says, “combining the elevation of lyricism and magician-ship of language with the power of great story-telling,” and for Goldman, of all of Williams’ work there stands what he calls “the holy trinity,” his own “personal pantheon” of Williams’ three greatest creations: “The Glass Menagerie” (1944), “Streetcar Named Desire” (1948) and “Camino Real” (1953). The latter is being performed in a staged reading directed by Goldman tonight at 7:45 p.m.

It’s been a year filled with drama and music, re-imaginings and new works. There was a lot on offer in 2025, and much to enjoy. Here are 10 now-closed productions that come to mind.

On Valentine’s Day at Folger Theatre on Capitol Hill, out actor Holly Twyford served as narrator for “The Love Birds” a Folger Consort work that melds medieval music with a world-premiere composition by acclaimed composer Juri Seo and readings from Geoffrey Chaucer’s “A Parlement of Foules”

Standing behind a podium, Twyford beautifully read Chaucer’s words (translated from Middle English and backed by projected slides in the original language), alternating with music played on old and new instruments.

While Mosaic Theater’s “A Case for the Existence of God,” closed in mid-December, it’s proving a production not soon forgotten. Precisely staged by Danilo Gambini, and impressively acted by Lee Orsorio and Jaysen Wright, the soul-searching two hander by out playwright Samuel D. Hunter, tells the story of two men who form an unlikely friendship based on single-fatherhood, a specific sadness, and hope.

The action unfolds in a small office in southern Idaho, where the pair discuss the perplexing terms of a mortgage loan while delving deep into their lives and backgrounds. Nothing is left off the table.

Shakespeare Theatre Company’s spring production of “Uncle Vanya” gave audiences something both fresh yet enduring. Staged by STC’s artistic director Simon Godwin, the production put an impeccably pleasing twist on Russian playwright Anton Chekhov’s classic. It ranks among the very best area productions of the year.

Featuring a topnotch cast led by Hugh Bonneville (TV’s “Downton Abbey”) in the title role, the play was set on an unfinished stage cluttered with costume racks and assorted props, all assembled by crew uniformed in black and actors in street clothes. Throughout the drama tinged with comedy, the actors continued to assist with ever increasingly period set changes accompanied by an underscore of melancholic cello strings. It was innovative and wonderful.

GALA Hispanic Theatre’s production of Manuel Puig’s “Kiss of the Spider Woman” was an intimate and affecting piece of theater. Staged by José Luis Arellano, it starred out actors Rodrigo Pedreira and Martín Ruiz as two very different men whose paths cross as convicts in an Argentine prison.

Arena Stage scored with a re-imagined and updated take on the widely liked musical “Damn Yankees.” Directed by Sergio Trujillo, the Broadway bound production has been “gently re-tooled for its first major revival in the 21st century,” moving the action from the struggling Washington Senators baseball team to the turn-of-the-century Yankees lineup. Ana Villafañe’s charmingly seductive Lola and a chorus of fit ball players made for a good time.

Also at Arena, out playwright Reggie D. White’s new work “Fremont Ave.” was very well received. A semi-autobiographical glimpse into home and the many definitions of that idea specifically relating to three generations of Black men, the work boasts a third act with a deeply queer storyline to boot.

Before his smash hit “Hamilton” transformed Broadway, Lin-Manuel Miranda wrote “In the Heights,” a seminal musical set against the vicissitudes of an upper Manhattan bodega. Infused with hip-hop, rap, and pop ballads, the romance/dramedy takes place over a lively few days in the vibrant, close-knit Latin neighborhood, Washington Heights.

Signature Theatre’s exciting take on “In the Heights” featured a talented cast including out actor Ángel Lozado as the bodega owner who figures prominently in the barrio and the action.

Studio Theatre’s recent production of lesbian playwright Paula Vogel’s newest work “The Mother Play,” a drama with humor, is about a well put together alcoholic mother and her two gay children living under difficult circumstances in the less glitzy parts of suburban Maryland. With nuanced performances and smart direction, the production was terrific.

Keegan Theatre surpassed expectations with its production of “Lizzie” a punk rock opera about Miss Borden, the fabled axe wielding title character. Performed by a super all-female cast, they belted a score that hits hard on subjects like money, queerness, and strained (to say the least) family relationships.

Round House Theatre impressed autumn audiences with “The Inheritance,” a two-part drama sensitively staged by out director Tom Story and acted by a mostly queer cast that included young actor Jordi Bertrán Ramírez in a breakout performance.

Penned by out playwright Matthew López, the epic work inspired by E.M. Forster’s novel “Howards End,” explores themes of love, legacy, and the AIDS crisis through the lives of three generations of gay men in New York City.

Prior to opening, Story commented that with the production’s predominately queer cast you get actors who “really understand the situation, the humor, and the struggle. It works well.” And he was right.

Theater

Out actor talks lead role in ‘Fiddler on the Roof’

Signature Theatre production runs through Jan. 25

‘Fiddler on the Roof’

Through Jan. 25

Signature Theatre

4200 Campbell Ave.

Arlington, Va.

Tickets start at $47

Sigtheatre.org

Out actor Ariel Neydavoud is deep into a three-month run playing revolutionary student Perchick in the beloved 1964 musical “Fiddler on the Roof” at Signature Theatre in Arlington. And like his previous gigs, it’s been a learning experience.

This time, he’s gleaning knowledge from celebrated gay actor Douglas Sills who’s starring as the show’s central character Tevya, a poor Jewish milkman in the fictional village of Anatevka in tsarist Russia circa 1905.

In addition to anti-Semitism and expulsion, Tevya is struggling with waning traditions in a changing world where his daughters dare suggest marrying for love. Daughter Hodel (Lily Burka) falls for Perchick, an outsider who comes to town brandishing new ideas.

And along with its compelling and humor filled storyline, “Fiddler” boasts iconic numbers like “If I Were a Rich Man,” “Tradition,” “Matchmaker, Matchmaker,” and “Sunrise, Sunset.”

Neydavoud, born and raised as an only child in the West Los Angeles neighborhood lightheartedly referred to as Tehrangeles (due to the large Iranian-American population), has always been passionate about performing. “It’s like I came out of the womb tap dancing,” he says. Fortunately, his mother, an accomplished pianist and composer, served as built-in accompanist.

He began acting and singing at kid camps and a private Jewish middle school alongside classmate Ben Platt. In his teens, Neydavoud spent three glorious weeks at Stagedoor Manor, a well-known theater camp in Upstate New York, where he solidified his desire to pursue theater as a profession, and started to feel comfortable with being queer.

Following high school, he studied at AMDA (American Musical and Dramatic Academy) and soon after morphed from theater student to professional actor.

WASHINGTON BLADE: Your entry into showbiz seems to have been a smooth one.

ARIEL NEYDAVOUD: I’m happy to hear it seems that way. I’d rarely describe anything about this profession as smooth; nonetheless, what I love about this work is that it gives opportunities to have so many new experiences: new shows, new parts, and new communities who come together in a moment’s notice purely for the sake of creating art.

BLADE: Tell us about Perchick.

NEYDAVOUD: He comes to Anatevka and challenges their ideals and way of life. That’s something I can relate to.

I’m Jewish on both sides, but I’m also queer, first generation American, [his mother and father are from Germany and Iran, respectively], and a person of color. I never feel like I belong to a single community. That’s what has emboldened my inner activist to speak up and challenge ideas that I don’t necessarily buy into.

BLADE: You sing beautifully. Perchick’s song is “Now I have Everything,” an Act II melody about finding love. Was it an instant fit for you?

NEYDAVOUD: Not instantly.I’m traditionally a first tenor. Perchick is baritone range, a little outside of my comfort zone. After being cast, I asked our director Joe Calarco if he would be comfortable raising the key, something they did with the recent Broadway revival. He was firm about not doing that.

As an artist I see challenges as opportunities to grow, so it’s been really good exploring my lower register.

BLADE: Audiences have commented on an intimacy surrounding this production.

TK: It’s performed in the round with a dining table at its center. It could be a sabbath or seder table, however you interpret it, but I find it a brilliant way to illustrate community and tradition.

It feels like the audience is invited to the table and join the residents of Anatevka. The show’s moments of joy like the betrothal song “To Life (L’Chaim)” are intensified, and conversely the pogrom scenes are made more difficult. It feels like we’re sharing space.

BLADE: Do your encompassing identities broaden casting possibilities for you?

NEYDAVOUD: Marketing yourself as ethnically ambiguous can be a helpful tool. After “Hamilton” and the pandemic there was more of a shift toward authenticity. I try to steer toward playing Middle Eastern, Southwest Asian, Jewish, and mixed-race characters without being too prescriptive.

BLADE: Tell us your dream roles?

NEYDAVOUD: I’d love to play the Emcee in Cabaret [often portrayed as a gender-fluid, queer-coded, or non-binary figure]. And I’d like to direct a production of “Godspell” with a fully Middle Eastern cast. I think portraying Jesus and disciples in Middle Eastern bodies as Bohemian idealists living under an oppressive regime could be especially impactful.

BLADE: Can today’s queer audiences relate to life on the shtetl?

NEYDAVOUD: As a piece, “Fiddler” is timeless. Beyond the magical score, it hits home with just about anyone who’s ever felt othered. There are relevant themes of displacement and persecution, and maintaining cultural identity in the wake of turbulence, all ideas that tend to resonate with queer people.

Theater

Studio’s ‘Mother Play’ draws from lesbian playwright’s past

A poignant memory piece laced with sadness and wry laughs

‘The Mother Play’

Through Jan. 4

Studio Theatre

1501 14th St., N.W.

$42 – $112

Studiotheatre.org

“The Mother Play” isn’t the first work by Pulitzer Prize-winning lesbian playwright Paula Vogel that draws from her past. It’s just the most recent.

Currently enjoying an extended run at Studio Theatre, “The Mother Play,” (also known as “The Mother Play: A Play in Five Evictions,” or more simply, “Mother Play”) is a 90-minute powerful and poignant memory piece laced with sadness and wry laughs.

The mother in question is Phyllis Herman (played exquisitely by Kate Eastwood Norris), a divorced government secretary bringing up two children under difficult circumstances. When we meet them it’s 1964 and the family is living in a depressing subterranean apartment adjacent to the building’s trash room.

Phyllis isn’t exactly cut out for single motherhood; an alcoholic chain-smoker with two gay offspring, Carl and Martha, both in their early teens, she seems beyond her depth.

In spite (or because of) the challenges, things are never dull in the Herman home. Phyllis is warring with landlords, drinking, or involved in some other domestic intrigue. At the same time, Carl is glued to books by authors like Jane Austen, and queer novelist Lytton Strachey, while Martha is charged with topping off mother’s drinks, not a mean feat.

Despite having an emotionally and physically withholding parent, adolescent Martha is finding her way. Fortunately, she has nurturing older brother Carl (the excellent Stanley Bahorek) who introduces her to queer classics like “The Well of Loneliness” by Radclyffe Hall, and encourages Martha to pursue lofty learning goals.

Zoe Mann’s Martha is just how you might imagine the young Vogel – bright, searching, and a tad awkward.

As the play moves through the decades, Martha becomes an increasingly confident young lesbian before sliding comfortably into early middle age. Over time, her attitude toward her mother becomes more sympathetic. It’s a convincing and pleasing performance.

Phyllis is big on appearances, mainly her own. She has good taste and a sharp eye for thrift store and Goodwill finds including Chanel or a Von Furstenberg wrap dress (which looks smashing on Eastwood Norris, by the way), crowned with the blonde wig of the moment.

Time and place figure heavily into Vogel’s play. The setting is specific: “A series of apartments in Prince George’s and Montgomery County from 1964 to the 21st century, from subbasement custodial units that would now be Section 8 housing to 3-bedroom units.”

Krit Robinson’s cunning set allows for quick costume and prop changes as decades seamlessly move from one to the next. And if by magic, projection designer Shawn Boyle periodically covers the walls with scurrying roaches, a persistent problem for these renters.

Margot Bordelon directs with sensitivity and nuance. Her take on Vogel’s tragicomedy hits all the marks.

Near the play’s end, there’s a scene sometimes referred to as “The Phyllis Ballet.” Here, mother sits onstage silently in front of her dressing table mirror. She is removed of artifice and oozes a mixture of vulnerability but not without some strength. It’s longish for a wordless scene, but Bordelon has paced it perfectly.

When Martha arranges a night of family fun with mom and now out and proud brother at Lost and Found (the legendary D.C. gay disco), the plan backfires spectacularly. Not long after, Phyllis’ desire for outside approval resurfaces tenfold, evidenced by extreme discomfort when Carl, her favorite child, becomes visibly ill with HIV/AIDS symptoms.

Other semi-autobiographical plays from the DMV native’s oeuvre include “The Baltimore Waltz,” a darkly funny, yet moving piece written in memory of her brother (Carl Vogel), who died of AIDS in 1988. The playwright additionally wrote “How I Learned to Drive,” an acclaimed play heavily inspired by her own experiences with sexual abuse as a teenager.

“The Mother Play” made its debut on Broadway in 2024, featuring Jessica Lange in the eponymous role, earning her a Tony Award nomination.

Like other real-life matriarch inspired characters (Mary Tyrone, Amanda Wingfield, Violet Weston to name a few) Phyllis Herman seems poised to join that pantheon of complicated, women.

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoWhat to watch for in 2026: midterms, Supreme Court, and more

-

Opinions5 days ago

Opinions5 days agoA reminder that Jan. 6 was ‘textbook terrorism’

-

Colombia5 days ago

Colombia5 days agoClaudia López criticizes Trump over threats against Colombian president

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoImperial Court of Washington drag group has ‘dissolved’