World

Mexicans with HIV/AIDS struggle with treatment access

Government in 2019 created new health care entity

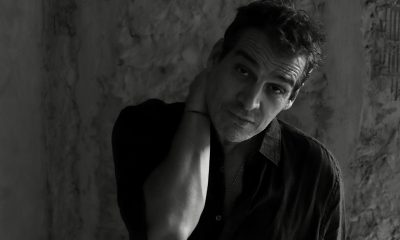

Roberto Navarro has been a dancer since he was 17. Jazz became his passion and he fell in love with classical dancing after he took many classes. And he began to teach four years later.

“I’m so happy when I teach dancing to my girls because they bring me so much joy, I feel like I help my girls to become better women, without noticing I’m some kind of a therapist,” Navarro told the Washington Blade.

He discovered the discipline of dancing in heels in 2014, which made him connect and explore more with his sexuality. He did, however, suffer a lot of bullying because of it.

Navarro — a 33-year-old gay man who is originally from Sahuayo de Morelos in Michoacán state — currently owns a dance salon. Navarro said he started to become an entrepreneur, but it hasn’t been easy because of the pandemic.

He was diagnosed with HIV in 2016. Navarro suffered from depression for several months after he learned his status.

“I woke up very overwhelmed in the morning thinking that I had to go to the hospital to make a long line of patients; to have blood drawn for fast screening tests,” he said. “We arrived at 7 in the morning and left until 1 in the afternoon.”

Navarro has been receiving treatment for almost five years, and he is still dancing.

“Subsequently, I went to my consultations every three or six months depending on my results,” he stated. “By the third month I was undetectable.”

Navarro started with Atripla, an antiretroviral drug he received through Mexico’s Seguro Popular, and he was undetectable a month later.

A shortage of Atripla forced a change to Biktarby after President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2019 scrapped Seguro Popular and created the Health Institute for Wellbeing (INSABI). The pharmaceutical company Gilead has said there are many counterfeit versions of the drug on the market.

Seguro Popular in 2018 had almost 52 million beneficiaries. The National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) said INSABI at the end of 2020 had more than 34 million beneficiaries.

Antiretroviral drugs have been available in Mexico since 2003, although the Mexican health system is divided into various subsystems based on where one works.

- Institute of Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE)

- Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMS)

- INSABI (Health Institute for Wellbeing) that was previously known as the Seguro Popular

They vary in the time it takes to receive medication and the time for CD4 viral load tests. The availability of appointments with infectious disease specialists varies in each of the three public health systems.

People with INSABI will take longer to get tests and have access to doctors. It must also be recognized that everyone, in theory, has the possibility of accessing medicines, but it also depends on the states in which they live.

From Seguro Popular to INSABI

The number of people without access to healthcare in Mexico rose from 20 million to almost 36 million between 2018-2020. INSABI, more than a year after its creation, still does not completely cover the same amount as its predecessor.

INSABI is an independent agency through the Ministry of Health that aims to “provide and ensure the free provision of health services, medicines and other inputs associated with people without social security.” The General Health Law says it was to replace Seguro Popular, which was in place from 2004-2019.

“The situation for treatment right now, it’s quite complex, particularly because there have been many changes in the health department of Mexico, and this has to do with the fact that in 2003 when the Seguro Popular was established; there was an increase to comprehensive care for people living with HIV and resources for prevention strategies which are mainly handled through civil society organizations that obtained money from the government.” stated Ricardo Baruch, who has worked at the International Family Planning Federation for almost 15 years.

López,, who took office in 2018, sought to eliminate Seguro Popular, which was the mechanism by which access to antiretroviral drugs were given to most people living with HIV in the states with greater vulnerability. This change was done in theory to expand access for everyone, but the opposite happened.

There is less access due to the modification of purchasing mechanisms and a huge shortage throughout the country. Baruch says this situation has caused a treatment crisis across Mexico.

“The truth is that the Seguro Popular helped me a lot to have my treatments on time, what I do not like is that there is not enough staff to attend all the patients that we are waiting for our consultations,” said Erick Vasquez, a person who learned in February he is living with HIV.

Vasquez, 34, is an artist who works in Guadalajara and Playa del Carmen.

Vasquez did not have health insurance like other people through IMS. He obtained access to Seguro Popular through an organization that supports people with HIV, but he has to wait until October for his first appointment.

Vasquez, who has a very low viral load, in March began a job through which he obtained IMS. He had access to his treatments through it.

He received three months worth of Biktarvy at the end of June; one prescription for each month. He said the drug is not difficult to obtain.

“I have not had any problem with the medication, it is not difficult to get it when you are on the insurance, but there is still a long time left until October,” said Vasquez.

The cost of the antiretroviral treatment in Mexico is approximately $650 per month, and one bottle has only 30 pills.

“I have not had side effects, I have not had nausea, I don’t vomit, I take a pill daily, it is one every 24 hours,” Vasquez said. “I feel very well and I hope very soon to be undetectable.”

Infrastructure over health

Prevention resources were eliminated, and health resources today are used to finance the Felipe Ángeles International Airport at the Santa Lucía military base in Zumpango in Mexico state, a new refinery, the Mayan train and other major infrastructure projects. And this causes many people who want to access treatment not to receive them. It takes much

The cost of the work, including the land connected with the Mexico City International Airport and various military facilities, is set at 82,136,100,000 Mexican pesos and there are provisions to serve 19.5 million passengers the first year of operations, according to a report from the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA).

There are, on the other hand, far fewer HIV tests and this shortage has led to a much higher arrival of late-stage HIV cases and even AIDS in hospitals. This trend is particularly serious among transgender women and men who have sex with men.

“Here in Mexico we concentrate the HIV pandemic, and that we are at a time when this issue of shortages has not stabilized, that there is already more clarity in purchases, but it is well known that all these changes in health systems continue for a year over the years they cause the situation to be increasingly fragile and in the matter of migrants that previously there was certainty so that they could access medicines through the Seguro Popular, now there is a legal limbo for which in some states it depends: on the states, the clinic or social worker; whether or not they give you medications,” said Baruch.

“If you are not a resident or a national here in Mexico, this is a matter won for people in transit seeking political asylum or who had stayed in Mexico,” he added.

Migrants lack access to HIV treatment

Mexico is located between the three regions with the world’s highest rates of HIV: the Caribbean, Central America, and the U.S. This has been used as a foundation for a culture of hatred against migrants, according to Siobhan McManus, a biologist, philosopher, and researcher at the Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Sciences and Humanities of the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

The lack of opportunities, violence and climate change that forces people whose livelihoods depend on agriculture to abandon their homes prompts migration from Central America.

Most migrants — LGBTQ or otherwise — experience violence once they arrive in Mexico.

Chiapas and other states have created an extensive network of clinics known by the Spanish acronym CAPASITS (Centro Ambulatorio para la Prevención y Atención en SIDA e Infecciones de Transmisión Sexual) that are specific HIV and STD units in major towns. They are often within close proximity to most people’s homes.

Sonora and Chihuahua states, which border the U.S., often have such clinics in only one or two cities. This lack of access means people will have to travel up to six hours to access these treatments.

People who have already been receiving treatment for a long time were previously given up to three months of treatment. They now must travel every month to receive their medications because of the shortages.

PrEP available in Mexico

The shortage of medical drugs for people who already live with HIV is a current issue for the Mexican government, but they have made free PrEP available for those who want to prevent themselves from the virus.

Ivan Plascencia, a 24-years old, who lives in Guadalajara, the capital of Jalisco state , has been using PrEP for several years since he became sexually active and he never had any complaints about the medication. Plascencia instead recommends his close friends to take advantage of this prevention drug that is available in one of the CAPASITS where he lives.

Post-pandemic screening tests

There are an estimated 260,000 people in Mexico who are living with HIV. Upwards of 80 percent of them knew their status before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The number of new cases that were detected in 2020 were 60 percent less than the previous year, but this figure does not mean HIV rates have decreased.

In Jalisco, which is one of Mexico’s most populous states with upwards of 8 million people, there was a 40 percent increase in positive cases in 2020 compared to 2019. This increase has put a strain on service providers.

Bulgaria

Top EU court issues landmark transgender rights ruling

Member states must allow name, gender changes on ID documents

The European Union’s highest court on Thursday ruled member states must allow transgender people to legally change their name and gender on ID documents.

The EU Court of Justice in Luxembourg issued the ruling in the case of “Shipova,” a trans woman from Bulgaria who moved to Italy.

“Shipova” had tried to change her gender and name on her Bulgarian ID documents, but courts denied her requests for nearly a decade.

A ruling the Bulgarian Supreme Court of Cassation issued in 2023 essentially banned trans people from legally changing their name and gender on ID documents. Two Bulgarian LGBTQ and intersex rights groups — the Bilitis Foundation and Deystvie — and ILGA-Europe and TGEU – Trans Europe and Central Asia supported the plaintiff and her lawyers.

“Because her life in Italy also depended on her Bulgarian documents, the lack of documents reflecting her lived gender creates an obstacle to her right to move and reside within EU member states,” said the groups in a press release. “This mismatch between her gender identity and expression and her gender marker in her official documents leads to discrimination in all areas of life where official documents are required. This includes everyday activities such as going to the doctor and paying for groceries by card, finding employment, enrolling in education, or obtaining housing.”

Denitsa Lyubenova, a lawyer with Desytvie, in the press release said the case “concerns the dignity, equality, and legal certainty of trans people in Bulgaria.” TGEU Senior Policy Officer Richard Köhler also praised the ruling.

“Today, the EU Court of Justice has taken an important step towards a right to legal gender recognition in the EU,” said Köhler. “Member states must allow their nationals living in another member state to change their gender data in public registries and identity cards to ensure they can fully enjoy their freedom of movement. National laws or courts cannot stand in their way.”

“Thousands of trans people in the EU are breathing a sigh of relief today,” added Köhler.

Senegal

Senegalese lawmakers approve bill to further criminalize homosexuality

A dozen men arrested in February for ‘unnatural acts’

Senegalese lawmakers on Wednesday approved a bill that would further criminalize consensual same-sex sexual relations in the country.

The Associated Press notes the measure that Prime Minister Ousmane Sonko introduced in February would increase the penalty for anyone convicted of engaging in consensual same-sex sexual relations from one to five years in prison to five to 10 years. The AP further indicates the bill would prohibit the “promotion” or “financing” of homosexuality in the country.

The bill passed with near unanimous support. Only three of 135 MPs abstained.

President Bassirou Diomaye Faye is expected to sign the measure.

The National Assembly in 2021 rejected a bill that would have further criminalized homosexuality in Senegal.

Senegalese police last month arrested a dozen men and charged them with committing “unnatural acts.”

Volker Türk, the U.N. high commissioner for human rights, in a statement described the bill as “deeply worrying.”

“It flies in the face of the sacrosanct human rights we all enjoy: the rights to respect, dignity, privacy, equality and freedoms of expression, association, and peaceful assembly,” he said.

Türk also urged Faye not to sign the bill.

“I urge the president not to sign this harmful law into effect, and for authorities to repeal the existing discriminatory law and to uphold the human rights of all in Senegal, without discrimination,” said Türk.

Malaysia

Malaysia blocks access to Grindr, other gay dating websites

Restrictions part of continued anti-LGBTQ crackdown

Malaysia has blocked access to Grindr, Blued, and other gay dating websites, and is now considering further steps to restrict their mobile application.

Communications Minister Fahmi Fadzil on Feb. 25 said the government is pursuing legal measures to curb the availability of LGBTQ dating apps on Google’s Play Store and Apple’s App Store.

Fadzil, in a written parliamentary reply, said the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission has not received any requests to remove the mobile versions of Grindr and Blued from app stores, noting the challenges of regulating platforms owned by foreign companies.

“Control over applications on platforms such as Google Play and Apple Store is subject to regulations and policies set by the said platform providers, since both applications are owned by foreign companies operating outside of Malaysia,” Fadzil said. “This includes those that spread lewd or immoral content, exploitation, abuse, scams, exploiting children or threats towards public safety.”

Fadzil was responding to a question about whether the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission had worked with app store providers to block downloads of such apps.

The Washington Blade reached out to Google and Apple multiple times for comment but did not receive a response.

Malaysia has stepped up digital restrictions targeting the LGBTQ community as part of a broader crackdown on what authorities describe as “deviant” or immoral content. Consensual same-sex sexual relations remain criminalized in the country under both civil and Sharia law.

Malaysia has proposed a Cyber Crime Bill that would expand the government’s legal powers to address the misuse of digital platforms, including the promotion of same-sex dating applications, Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi said. The bill would replace the Computer Crimes Act of 1997.

“We are disappointed in the decision to block access to Grindr in Malaysia and believe that online platform regulation should be proportionate and consistent with international human rights law,” a Grindr spokesperson told the Blade in an email.

“At Grindr, our mission is to help make a world where the lives of our global community are free, equal, and just,” added the spokesperson. “For many of our users, Grindr is often the primary way for them to connect, express themselves, and discover the world around them. In addition to serving as an important source of information, Grindr is committed to advancing the health and well-being of the community around the world and through our social impact initiative, Grindr for Equality, we partner with hundreds of advocates, community-based organizations, and public health agencies to support the global LGBTQ+ community.”

Grindr, based in California, is popular around the world. Blued, a China-based app that BlueCity operates, is one of the world’s largest social networking and dating platforms for gay men.

Blued did not respond to the Blade’s request for comment.

Online platforms ‘critical for LGBTQ people’

Malaysian authorities in May 2023 raided Swatch stores at shopping malls across the country and confiscated more than 160 rainbow-colored watches from the company’s Pride collection, saying the designs carried “LGBT connotations.” The raids, which the Home Affairs Ministry carried out, were widely criticized by advocacy groups.

Police last June opened an investigation into a closed-door LGBTQ sexual health workshop.

Selangor police chief Hussein Omar Khan said authorities were examining the event under the Penal Code for allegedly causing “disharmony or ill will” on religious grounds, as well as under the Communications and Multimedia Act, a law frequently used to police online speech. Critics said the investigation reflected growing government overreach and warned against the criminalization of public health initiatives aimed at marginalized communities. Activists cited this case as another example of Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s crackdown on LGBTQ rights.

The Home Affairs Ministry in November 2020 banned the book “Gay Is OK! A Christian Perspective,” written by Pastor Oyoung and published by Gerakbudaya in 2013, saying it was likely to be “prejudicial to public order, morality and the public interest.” The Kuala Lumpur High Court later overturned the ban and ordered the respondents — then-Home Affairs Minister Hamzah Zainudin and the Malaysian government — to pay costs of 5,000 Malaysian ringgit ($1,276.81.)

A 2014 Human Rights Watch report documented widespread discrimination and abuse against transgender women in the country.

The report found that trans people face arrests under laws that effectively criminalize “cross-dressing,” along with harassment and abuse by police and religious authorities. It also described systemic discrimination in employment, health care, and education, leaving many trans women marginalized and vulnerable to violence and exploitation.

Thilaga Sulathireh, a founding member of Justice for Sisters, a Malaysian trans rights group, said restrictions on LGBTQ people’s freedom of expression through censorship have been an ongoing trend in Malaysia over the past decade.

Sulathireh said there have been increasing calls to curb what critics describe as “LGBT normalization” in films, books, and social media, which activists link to what they say is a harmful and inaccurate perception that LGBTQ people are immoral. Sulathireh added Grindr had been blocked in Malaysia for several years and that, as of last weekend, the app was no longer available on Google Play and the Apple App Store. Sulathireh said Justice for Sisters views the move as a serious violation of LGBTQ people’s rights to nondiscrimination, dignity, privacy, and freedom of expression.

“The blocking of LGBTQ related apps is part of the on-going and increasing trend of state sponsored discrimination against LGBTQ people in Malaysia,” Sulathireh told the Blade in an email. “In late February, the deputy minister in the prime minister’s (Religious Affairs) Department announced that the government is opting to replace references to LGBT persons with the term “budaya songsang” (deviant culture) and encouraged others to do the same to avoid LGBT normalization in all spaces, including social media. At the same time, called on members of the public to immediately report ‘suspicious activities, events or content.’”

Sulathireh told the Blade a deputy minister recently outlined a range of government-led initiatives targeting LGBTQ people in Malaysia.

According to Sulathireh, these include so-called “spiritual guidance camps.” Sulathireh said some participants, including those who identify as “ex-LGBT” or part of the “hijrah” community, have been encouraged to act as peer educators to reach other LGBTQ people.

Additional initiatives the deputy minister listed include academic Islamic conferences, state-level sermons coordinated by the state Islamic councils, and mosque-level programs. Sulathireh told the Blade the government presented a paper to the Council of Rulers outlining what officials described as the negative implications of legal gender recognition. Sulathireh said authorities have also established a multiagency committee to address issues involving Muslim LGBTQ people, promoted what they call “psychospiritual therapy,” and worked with police and the Communications and Multimedia Commission to monitor the promotion of LGBTQ-related activities online.

“The blocking of these apps and websites severely impacts all areas of LGBTQ people’s lives,” said Sulathireh. “These platforms have proven critical for LGBTQ people to find support, communities, access life-saving resources, information and services, love and intimacy. I think being able to find love, intimacy and connections is critical for LGBTQ’s self-acceptance, self-worth, health, and well-being.”

“The blocking makes it even more challenging for people to connect safely online and offline,” added Sulathireh. “People will become more isolated and all of these have a severe impact on LGBTQ’s mental health and well-being, which is already poor.”

Sulathireh said Justice for Sisters research and observations indicate many LGBTQ people in Malaysia already experience social media and digital spaces as hostile environments. As a result, many limit their use of these platforms and adopt higher levels of self-censorship. Sulathireh added the recent bans targeting LGBTQ visibility on digital platforms are also unfolding alongside a broader policy push to restrict social media access for children under 16.

“The state sponsored LGBTQ discrimination over the years has resulted in increasing discrimination by non-state actors and anti-rights groups with impunity,” Sulathireh said. “This ban will further entrench the culture of impunity against LGBTQ people.”

Nalini Elumalai, senior Malaysia program officer at ARTICLE 19, an international freedom of expression organization, said the blocking of dating apps is not occurring in isolation but is happening under the guise of public morality, digital censorship, and the enforcement of laws that undermine the rights of LGBTQ individuals in Malaysia.

Elumalai noted that Deputy Religious Affairs Minister Marhamah Rosli recently urged the public to refrain from using the term “LGBT” and instead describe it as “deviant culture” in an effort to combat normalization and reduce LGBTQ-related content on social media. Elumalai said blocking Grindr and Blued represents an ongoing attack on the LGBTQ community, particularly their rights to freedom of expression, access to information, and to be treated equally before the law without discrimination — protections guaranteed under Articles 8 and 10 of Malaysia’s Federal Constitution.

“The blocking of LGBTQI+ dating platforms appears to reflect a broader pattern in Malaysia where LGBTQI+-related expression and activities face heightened scrutiny and repression, particularly when they become visible online,” said Elumalai in a statement to the Blade.

Elumalai noted JEJAKA, a community-based organization had to cancel their “Glamping with Pride” event that was to have taken place on Jan. 17-18 because of safety concerns after it received death threats on social media.

“Ongoing repression of LGBTQI+ expression will further entrench systemic discrimination against marginalized groups, normalise inequality, and perpetuate division and hostility among the people in Malaysia,” said Elumalai. “Further, when one group is punished or prevented from expressing themselves freely online, others, including various online platforms, may also self-censor out of fear that they too could face scrutiny or penalties, even for legitimate expressions.”

The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission has not responded to the Blade’s request for comment.

-

Health4 days ago

Health4 days agoToo afraid to leave home: ICE’s toll on Latino HIV care

-

Movies4 days ago

Movies4 days agoIntense doc offers transcendent treatment of queer fetish pioneer

-

Colombia4 days ago

Colombia4 days agoClaudia López wins primary in Colombian presidential race

-

The White House3 days ago

The White House3 days agoTrump will refuse to sign voting bill without anti-trans provisions