Books

After 1,000 pages, you’ll hunger for more Highsmith

Acclaimed queer novelist revealed in new tome of diaries

‘Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks: 1941-1995′

Edited by Anna Von Planta

c.2020, Liveright

$39.95/1,024 pages

“The unfortunate truth is that art sometimes thrives on unhappiness,” queer novelist Patricia Highsmith, who lived from 1921 to 1995, wrote in her journals.

Fortunately, for aficionados of charming murderers, Hitchcock and queer folk on the cultural scene decades before Stonewall, this was true for Highsmith.

The creative process will always remain mysterious. Yet, in “Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks: 1941-1995,” brilliantly edited by Anna Von Planta, we gain insight into how Highsmith made art while living a hard-working, hard-drinking, hard-loving life. Along with gossip and fascinating glimpses of Highsmith’s travels.

But fair warning: seeing how literary sausage is made isn’t always pretty.

Highsmith lived an often unhappy, misanthropic life. As she got older, she came to prefer snails to people and dedicated one of her books to her cat.

Yet, Highsmith created more art than most of us could even dream of.

Over half a century, Highsmith wrote numerous short stories and 22 novels. Some of her best-known works are embedded in the cultural landscape.

Her novel “Strangers on a Train” was made into an unforgettable movie with the same name by Alfred Hitchcock. If you can sleep soundly after watching the amusement park scene in “Strangers,” you’re a more intrepid movie fan than I.

Her 1952 novel “The Price of Salt” (later reissued as “Carol”) is one of the first novels to feature lesbian characters with a happy ending. (The characters don’t die or go to prison.) In 2015, “Carol” was made into a movie by Todd Haynes.

Her Ripley novels featuring the captivating murderer Tom Ripley have also been adapted into movies.

If you’re entranced by murder, you’re likely a Highsmith fan. And, you’re in good company. Gore Vidal called Highsmith “one of our great modernist writers.” Graham Greene dubbed her “the poet of apprehension.”

Sometimes an iconic writer’s work stops being relatable. Not so with Highsmith.

Her novels, in which murderers routinely disguise themselves and identities shift, are more timely than ever in this age of avatars and catfishing.

A film adaptation of HIghsmith’s novel “Deep Water,” starring Ben Affleck and Ana de Armas, is forthcoming in 2022.

Yet, despite her popularity, during her lifetime, Highsmith hid much of her private life.

Born in Texas, she went to Barnard College and lived in Greenwich Village in New York in the 1940s. After that, she lived in Europe.

Her last home in Switzerland, her friends said, was “practically windowless.” They likened it to “Hitler’s bunker.”

It’s not surprising that Anna Von Planta has said that it took 25 years to edit Highsmith’s diaries and notebooks.

At some 1,000 pages, the volume is a lot to read. Yet, after Highsmith died, 8,000 pages of diaries and notebooks were found.

Unless you’re an indefatigable, insatiable scholar or fan, you wouldn’t want to read Highsmith’s diaries and notebooks in one sitting. It would be like eating five holiday feasts without a break. No matter how delicious, the food would be too filling, and, boring, by the fifth go-around.

These journals and notebooks are meant to be dipped into and savored morsel by morsel.

In her diary entries, Highsmith recorded the events of her life – the gossip, the sex, the drinking, the break-ups – the parties.

“Why can’t I go to a resort, pick up a girl, have a whirl, and drop her?” Highsmith writes in her diary in June 1950.

Highsmith’s notebook entries contained her thoughts on writing and writers. “Why writers drink: they must change their identities a million times in their writing,” Highsmith writes in a August 1951 notebook entry. “This is tiring, but drinking does it automatically for them. One minute they are a king, the next a murderer, a jaded dilettante, a passionate and forsaken lover.”

In her journals, Highsmith is witty, observant, bitter, narcissistic and bigoted (as, when, as she aged, she became increasingly anti-Semitic). But, she is, always, alive.

“I am ravenously hungry for a woman” she writes in her diary in 1950.

Long after reading Highsmith’s last journal entry, where she writes “death’s more like life, unpredictable,” you’ll hunger for more Highsmith.

Books

‘The Vampire Chronicles’ inspire LGBTQ people around the world

AMC’s ‘Interview with the Vampire’ has brought feelings back to live

Four kids pedaled furiously, their bicycles wobbling over cracked pavement and uneven curbs. Laughter and shouted arguments about which mystical creature could beat which echoed down the quiet street. They carried backpacks stuffed with well-worn paperbacks — comic books and fantasy novels — each child lost in a private world of monsters, magic, and secret codes. The air hummed with the kind of adventure that exists only at the edge of imagination, shaped by an imaginary world created in another part of the planet.

This is not a description of “Stranger Things,” nor of an American suburb in the 1980s. This is a small Russian village in the early 2000s — a place without paved roads, where most houses had no running water or central heating — where I spent every summer of my childhood. Those kids were my friends, and the world we were obsessed with was “The Vampire Chronicles” by Anne Rice.

We didn’t yet know that one of us would soon come out as openly bi, or that another — me — would become an LGBTQ activist. We were reading our first queer story in Anne Rice’s books. My first queer story. It felt wrong. And it felt extremely right. I haven’t accepted that I’m queer yet, but the easiness queerness was discussed in books helped.

Now, with AMC’s “Interview with the Vampire,” starring Jacob Anderson as Louis de Pointe du Lac — a visibly human, openly queer, aching vampire — and Sam Reid as Lestat de Lioncourt, something old has stirred back to life. Louis remains haunted by what he is and what he has done. Lestat, meanwhile, is neither hero nor villain. He desires without apology, and survives without shame.

I remember my bi friend — who was struggling with a difficult family — identifying with Lestat. Long before she came out, I already saw her queerness reflected there. “The Vampire Chronicles” allowed both of us to come out, at least to each other, with surprising ease despite the queerphobic environment.

While watching — and rewatching — the series over this winter holiday, I kept thinking about what this story has meant, and still means, for queer youth and queer people worldwide. Once again, this is not just about “the West.” I read comments from queer Ukrainian teenagers living under bombardment, finding joy in the show. I saw Russian fans furious at the absurdly censored translation by Amediateca, which rendered “boyfriend” as “friend” or even “pal,” turning the central relationship between two queer vampires into near-comic nonsense. Mentions of Putin were also erased from the modern adaptation — part of a broader Russian effort to eliminate queer visibility and political critique altogether.

And yet, fans persist to know the real story. Even those outside the LGBTQ community search for uncensored translations or watch with subtitles. A new generation of Eastern European queers is finding itself through this series.

It made me reflect on the role of mass culture — especially American mass culture — globally. I use Ukraine and Russia as examples because I’m from Ukraine, spent much of my childhood and adolescence in Russia, and speak both languages. But the impact is clearly broader. The evolution of mass culture changes the world, and in the context of queer history, “Interview with the Vampire” is one of the brightest examples — precisely because of its international reach and because it was never marketed as “gay literature,” but as gothic horror for a general audience.

With AMC now producing a third season, “The Vampire Lestat,” I’ve seen renewed speculation about Lestat’s queerness and debates about how explicitly the show portrays same-sex relationships. In the books, vampires cannot have sex in a “traditional” way, but that never stopped Anne Rice from depicting deeply homoromantic relationships, charged with unmistakable homoerotic tension. This is, after all, a story about two men who “adopt” a child and form a de facto queer family. And this is just the first book — in later novels we see a lot of openly queer couples and relationships.

The first novel, “Interview with the Vampire” was published in 1976, so the absence of explicit gay sex scenes is unsurprising. Later, Anne Rice — who identified as queer — described herself as lacking a sense of gender, seeing herself as a gay man and viewing the world in a “bisexual way.” She openly confirmed that all her vampires are bisexual: a benefit of the Dark Gift, where gender becomes irrelevant.

This is why her work resonates so powerfully with queer readers worldwide, and why so many recognize themselves in her vampires. For many young people I know from Eastern Europe, “Interview with the Vampire” was the first book in which they ever encountered a same-sex relationship.

But the true power of this universe lies in the fact that it was not created only for queer audiences. I know conservative Muslims with deeply traditional views who loved “The Vampire Chronicles” as teenagers. I know straight Western couples who did too. Even people who initially found same-sex relationships unsettling often became more tolerant after reading the books, watching the movie or the show. It is harder to hate someone who reminds you of a beloved character.

That is the strength of the story: it was never framed as explicitly queer or purely romantic, gothic and geeky audiences love it. “The Vampire Chronicles” are not a cure for queerphobia, but they are a powerful tool for making queerness more accessible. Popular culture offers a window into queer lives — and the broader that window, the more powerful it becomes.

Other examples include Will from “Stranger Things,” Ellie and Dina from “The Last of Us” (both the game and the series), or even the less mainstream but influential sci-fi show “Severance.” These stories allow audiences around the world to see queer people beyond stereotypes. That is the power of representation — not just for queer people themselves, but for society as a whole. It makes queer people look like real people, even when they are controversial blood-drinkers with fangs, or two girls surviving a fungal apocalypse.

Mass culture is a universal language, spoken worldwide. And that is precisely why censorship so often tries — and fails — to silence it.

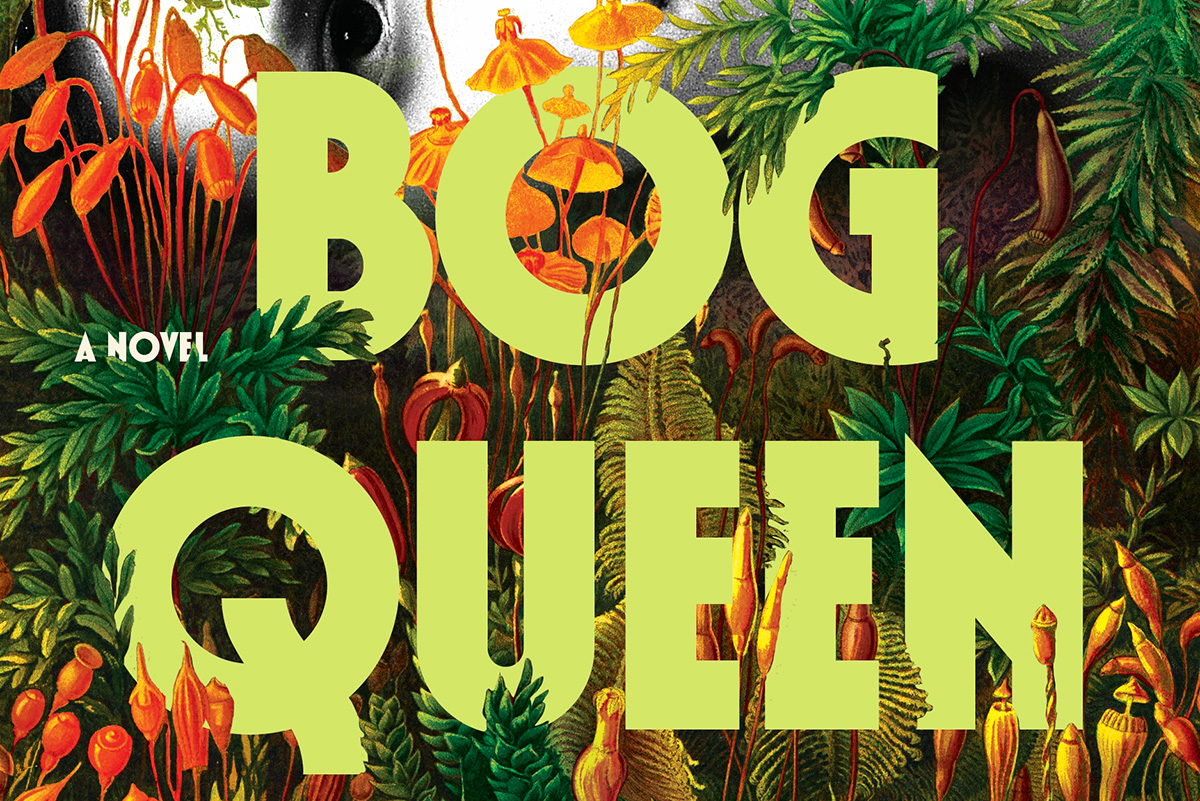

Books

Feminist fiction fans will love ‘Bog Queen’

A wonderful tale of druids, warriors, scheming kings, and a scientist

‘Bog Queen’

By Anna North

c.2025, Bloomsbury

$28.99/288 pages

Consider: lost and found.

The first one is miserable – whatever you need or want is gone, maybe for good. The second one can be joyful, a celebration of great relief and a reminder to look in the same spot next time you need that which you first lost. Loss hurts. But as in the new novel, “Bog Queen” by Anna North, discovery isn’t always without pain.

He’d always stuck to the story.

In 1961, or so he claimed, Isabel Navarro argued with her husband, as they had many times. At one point, she stalked out. Done. Gone, but there was always doubt – and now it seemed he’d been lying for decades: when peat cutters discovered the body of a young woman near his home in northwest England, Navarro finally admitted that he’d killed Isabel and dumped her corpse into a bog.

Officials prepared to charge him.

But again, that doubt. The body, as forensic anthropologist Agnes Lundstrom discovered rather quickly, was not that of Isabel. This bog woman had nearly healed wounds and her head showed old skull fractures. Her skin glowed yellow from decaying moss that her body had steeped in. No, the corpse in the bog was not from a half-century ago.

She was roughly 2,000 years old.

But who was the woman from the bog? Knowing more about her would’ve been a nice distraction for Agnes; she’d left America to move to England, left her father and a man she might have loved once, with the hope that her life could be different. She disliked solitude but she felt awkward around people, including the environmental activists, politicians, and others surrounding the discovery of the Iron Age corpse.

Was the woman beloved? Agnes could tell that she’d obviously been well cared-for, and relatively healthy despite the injuries she’d sustained. If there were any artifacts left in the bog, Agnes would have the answers she wanted. If only Isabel’s family, the activists, and authorities could come together and grant her more time.

Fortunately, that’s what you get inside “Bog Queen”: time, spanning from the Iron Age and the story of a young, inexperienced druid who’s hoping to forge ties with a southern kingdom; to 2018, the year in which the modern portion of this book is set.

Yes, you get both.

Yes, you’ll devour them.

Taking parts of a true story, author Anna North spins a wonderful tale of druids, vengeful warriors, scheming kings, and a scientist who’s as much of a genius as she is a nerd. The tale of the two women swings back and forth between chapters and eras, mixed with female strength and twenty-first century concerns. Even better, these perfectly mixed parts are occasionally joined by a third entity that adds a delicious note of darkness, as if whatever happens can be erased in a moment.

Nah, don’t even think about resisting.

If you’re a fan of feminist fiction, science, or novels featuring kings, druids, and Celtic history, don’t wait. “Bog Queen” is your book. Look. You’ll be glad you found it.

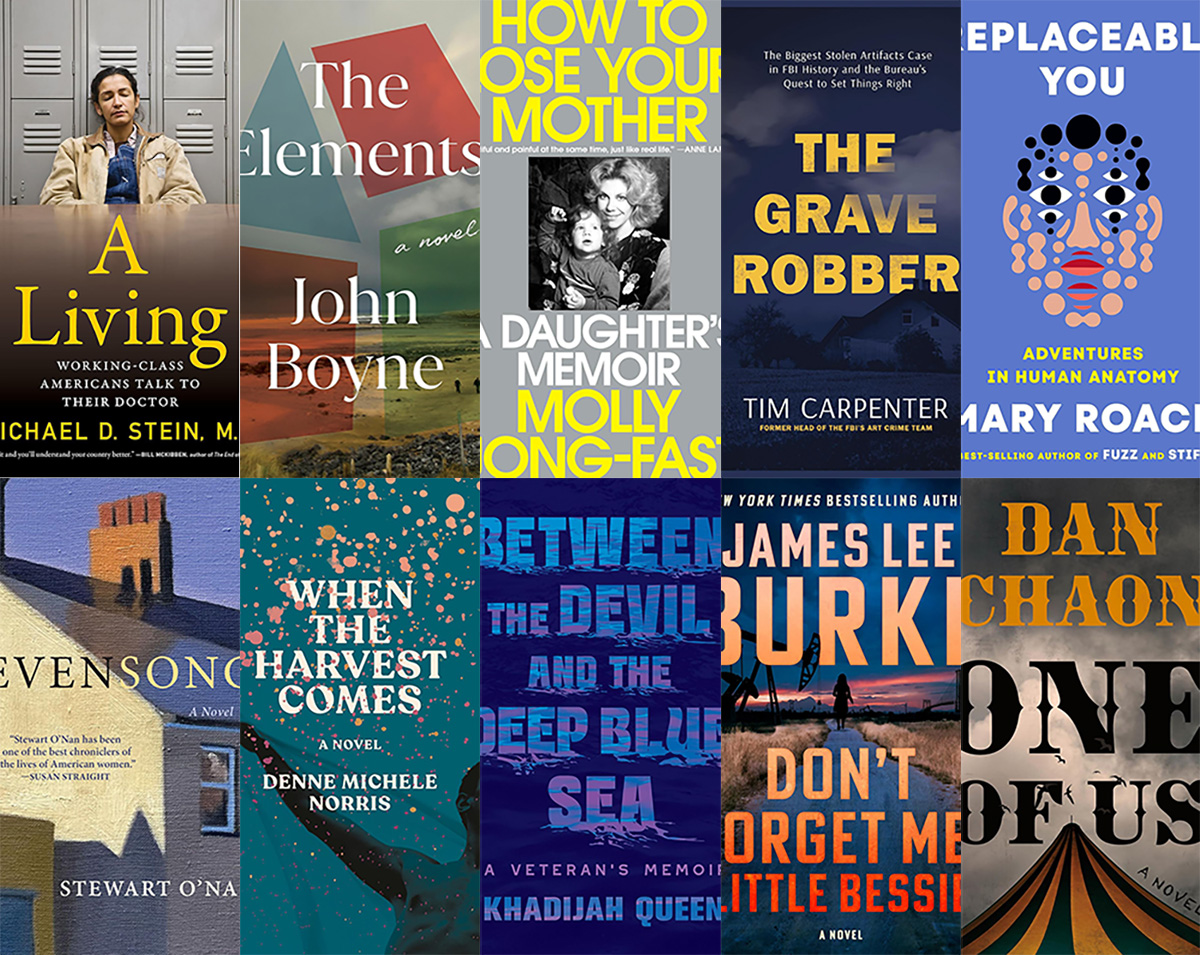

This past year, you’ve often had to make do.

Saving money here, resources there, being inventive and innovative. It’s a talent you’ve honed, but isn’t it time to have the best? Yep, so grab these Ten Best of 2025 books for your new year pleasures.

Nonfiction

Health care is on everyone’s mind now, and “A Living: Working-Class Americans Talk to Their Doctor” by Michael D. Stein, M.D. (Melville House, $26.99) lets you peek into health care from the point of view of a doctor who treats “front-line workers” and those who experience poverty and homelessness. It’s shocking, an eye-opening book, a skinny, quick-to-read one that needs to be read now.

If you’ve been doing eldercare or caring for any loved one, then “How to Lose Your Mother: A Daughter’s Memoir” by Molly Jong-Fast (Viking, $28) needs to be in your plans for the coming year. It’s a memoir, but also a biography of Jong-Fast’s mother, Erica Jong, and the story of love, illness, and living through the chaos of serious disease with humor and grace. You’ll like this book especially if you were a fan of the author’s late mother.

Another memoir you can’t miss this year is “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: A Veteran’s Memoir” by Khadijah Queen (Legacy Lit, $30.00). It’s the story of one woman’s determination to get out of poverty and get an education, and to keep her head above water while she goes below water by joining the U.S. Navy. This is a story that will keep you glued to your seat, all the way through.

Self-improvement is something you might think about tackling in the new year, and “Replaceable You: Adventures in Human Anatomy” by Mary Roach (W.W. Norton & Company, $28.99) is a lighthearted – yet real and informative – look at the things inside and outside your body that can be replaced or changed. New nose job? Transplant, new dental work? Learn how you can become the Bionic Person in real life, and laugh while you’re doing it.

The science lover inside you will want to read “The Grave Robber: The Biggest Stolen Artifacts Case in FBI History and the Bureau’s Quest to Set Things Right” by Tim Carpenter (Harper Horizon, $29.99). A history lover will also want it, as will anyone with a craving for true crime, memoir, FBI procedural books, and travel books. It’s the story of a man who spent his life stealing objects from graves around the world, and an FBI agent’s obsession with securing the objects and returning them. It’s a fascinating read, with just a little bit of gruesome thrown in for fun.

Fiction

Speaking of a little bit of scariness, “Don’t Forget Me, Little Bessie” by James Lee Burke (Atlantic Monthly Press, $28) is the story of a girl named Bessie and her involvement with a cloven-hooved being who dogs her all her life. Set in still-wild south Texas, it’s a little bit western, part paranormal, and completely full of enjoyment.

“Evensong” by Stewart O’Nan (Atlantic Monthly Press, $28) is a layered novel of women’s friendships as they age together and support one another. The characters are warm and funny, there are a few times when your heart will sit in your throat, and you won’t be sorry you read it. It’s just plain irresistible.

If you need a dark tale for what’s left of a dark winter season, then “One of Us” by Dan Chaon (Henry Holt, $28), it it. It’s the story of twins who become orphaned when their Mama dies, ending up with a man who owns a traveling freak show, and who promises to care for them. But they can’t ever forget that a nefarious con man is looking for them; those kids can talk to one another without saying a word, and he’s going to make lots of money off them. This is a sharp, clever novel that fans of the “circus” genre shouldn’t miss.

“When the Harvest Comes” by Denne Michele Norris (Random House, $28) is a wonderful romance, a boy-meets-boy with a little spice and a lot of strife. Davis loves Everett but as their wedding day draws near, doubts begin to creep in. There’s homophobia on both sides of their families, and no small amount of racism. Beware that there’s some light explicitness in this book, but if you love a good love story, you’ll love this.

Another layered tale you’ll enjoy is “The Elements” by John Boyne (Henry Holt, $29.99), a twisty bunch of short stories that connect in a series of arcs that begin on an island near Dublin. It’s about love, death, revenge, and horror, a little like The Twilight Zone, but without the paranormal. You won’t want to put down, so be warned.

If you need more ideas, head to your local library or bookstore and ask the staff there for their favorite reads of 2025. They’ll fill your book bag and your new year with goodness.

Season’s readings!

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.