Books

A fascinating tale of Paris and literature in early 20th century

If you love books and sexual freedom you’ll adore ‘The Paris Bookseller’

‘The Paris Bookseller’

By Kerri Maher

c. 2022, Berkley

$26/336 pages

In LGBTQ bars, men dance with men and women kiss women. In artistic neighborhoods, straight people dine and drink with their queer friends. Queer couples and throuples are among the leaders of the avant-garde. Yet, there’s some repression. Books are banned.

You might think such goings-on can only be found in a present-day gayborhood or cultural hotspot.

But, this isn’t just a 21-century tableau. It was the scene a century ago in Paris where queer and hetero artists and writers, flirting, dancing, making art, drinking, dining and partying together, created some of the most acclaimed writing of the 20th century.

At the center of it all was Sylvia Beach and her bookshop Shakespeare and Company.

“The Paris Bookseller,” a new novel by Kerri Maher, brings us into the creative, diverting world of Paris from 1917 to 1936. Many titans of modernist art and literature thrived there (often before they were famous) – from Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas to Ernest Hemingway to Ezra Pound to Andre Gide to Paul Valery to James Joyce. Some were French. Others were American, British, Irish, or Canadian expats.

Sylvia Beach, a bookish American lesbian, who loved Paris, writers, books, and especially, her bookshop, was the friend, librarian, sometimes publisher, hand-holder – den mother – of this community.

Maher has given readers a fab work of historical fiction. Much has been written about Joyce, Stein, Hemingway and their gang. But comparatively little has been written about Beach, who lived from 1887 to 1962.

Beach lived openly for years with her lover and business partner Adrienne Monnier, and published Joyce’s groundbreaking novel “Ulysses,” which had run into censorship.

“The Bookseller” is a fascinating tale of the day-to-day life of Shakespeare and Company, the cultural hub, that nurtured the post-World War I generation of writers and artists.

Told from Beach’s point of view, the novel brings us inside Beach’s solar plexus as she delights in cafes and literary readings; strokes Joyce’s cranky ego and, later, with Monnier, faces the economic hardships of the Depression.

Beach was born in Baltimore. Her father was a Presbyterian minister and her mother supported women’s suffrage. Beach had two sisters – Holly and Cyprian, an actress who was also a lesbian.

In 1901, Beach moved with her family to Paris when her father was appointed assistant minister of the American Church in Paris. She lived in Princeton, N.J., for a time when her father was a minister there.

She then lived in Spain and worked for the Red Cross’ Balkan Commission of the Red Cross. As a volunteer in World War I, she did arduous farm work in Touraine, France.

But Paris had captured Beach’s heart. “Nothing compared to Paris,” Beach thought on her return to the City of Light, “not knocking on doors with Cyprian and Holly and Mother for the National Woman’s Party in New York; not her first longed-for kiss with her classmate Gemma Bradford; not winning the praise of her favorite teachers.”

If you like novels that make your heart pound with tension every nano-sec, “The Paris Bookseller” may not be the book for you. There are no severed heads. Gertrude Stein takes a few digs at Beach. There’s some snark. Monnier and Beach privately refer to Joyce as the “crooked Jesus” because he can be so annoying. But no knives are taken out.

Yet, “The Paris Bookseller” in its cozy, elegant way has more than its share of drama. It feels relatable to today – when increasing numbers of books are being banned.

Because being gay has been decriminalized in France since the French Revolution, LGBTQ people could live openly in post World War I Paris.

Yet there was a backlash against this freedom.

“Ulysses” was banned because it was thought to be obscene. Against this backdrop, a century ago, on Feb. 2, 1922, Beach published “Ulysses.”

Maher deftly engulfs us in the exaltation, joy, pain, and financial difficulties that Beach endured in dealing with Joyce and publishing his masterpiece.

If you love Paris, cafes, books, difficult geniuses, sexual freedom and censorship battles, you’ll adore “The Paris Bookseller.”

Books

Feminist fiction fans will love ‘Bog Queen’

A wonderful tale of druids, warriors, scheming kings, and a scientist

‘Bog Queen’

By Anna North

c.2025, Bloomsbury

$28.99/288 pages

Consider: lost and found.

The first one is miserable – whatever you need or want is gone, maybe for good. The second one can be joyful, a celebration of great relief and a reminder to look in the same spot next time you need that which you first lost. Loss hurts. But as in the new novel, “Bog Queen” by Anna North, discovery isn’t always without pain.

He’d always stuck to the story.

In 1961, or so he claimed, Isabel Navarro argued with her husband, as they had many times. At one point, she stalked out. Done. Gone, but there was always doubt – and now it seemed he’d been lying for decades: when peat cutters discovered the body of a young woman near his home in northwest England, Navarro finally admitted that he’d killed Isabel and dumped her corpse into a bog.

Officials prepared to charge him.

But again, that doubt. The body, as forensic anthropologist Agnes Lundstrom discovered rather quickly, was not that of Isabel. This bog woman had nearly healed wounds and her head showed old skull fractures. Her skin glowed yellow from decaying moss that her body had steeped in. No, the corpse in the bog was not from a half-century ago.

She was roughly 2,000 years old.

But who was the woman from the bog? Knowing more about her would’ve been a nice distraction for Agnes; she’d left America to move to England, left her father and a man she might have loved once, with the hope that her life could be different. She disliked solitude but she felt awkward around people, including the environmental activists, politicians, and others surrounding the discovery of the Iron Age corpse.

Was the woman beloved? Agnes could tell that she’d obviously been well cared-for, and relatively healthy despite the injuries she’d sustained. If there were any artifacts left in the bog, Agnes would have the answers she wanted. If only Isabel’s family, the activists, and authorities could come together and grant her more time.

Fortunately, that’s what you get inside “Bog Queen”: time, spanning from the Iron Age and the story of a young, inexperienced druid who’s hoping to forge ties with a southern kingdom; to 2018, the year in which the modern portion of this book is set.

Yes, you get both.

Yes, you’ll devour them.

Taking parts of a true story, author Anna North spins a wonderful tale of druids, vengeful warriors, scheming kings, and a scientist who’s as much of a genius as she is a nerd. The tale of the two women swings back and forth between chapters and eras, mixed with female strength and twenty-first century concerns. Even better, these perfectly mixed parts are occasionally joined by a third entity that adds a delicious note of darkness, as if whatever happens can be erased in a moment.

Nah, don’t even think about resisting.

If you’re a fan of feminist fiction, science, or novels featuring kings, druids, and Celtic history, don’t wait. “Bog Queen” is your book. Look. You’ll be glad you found it.

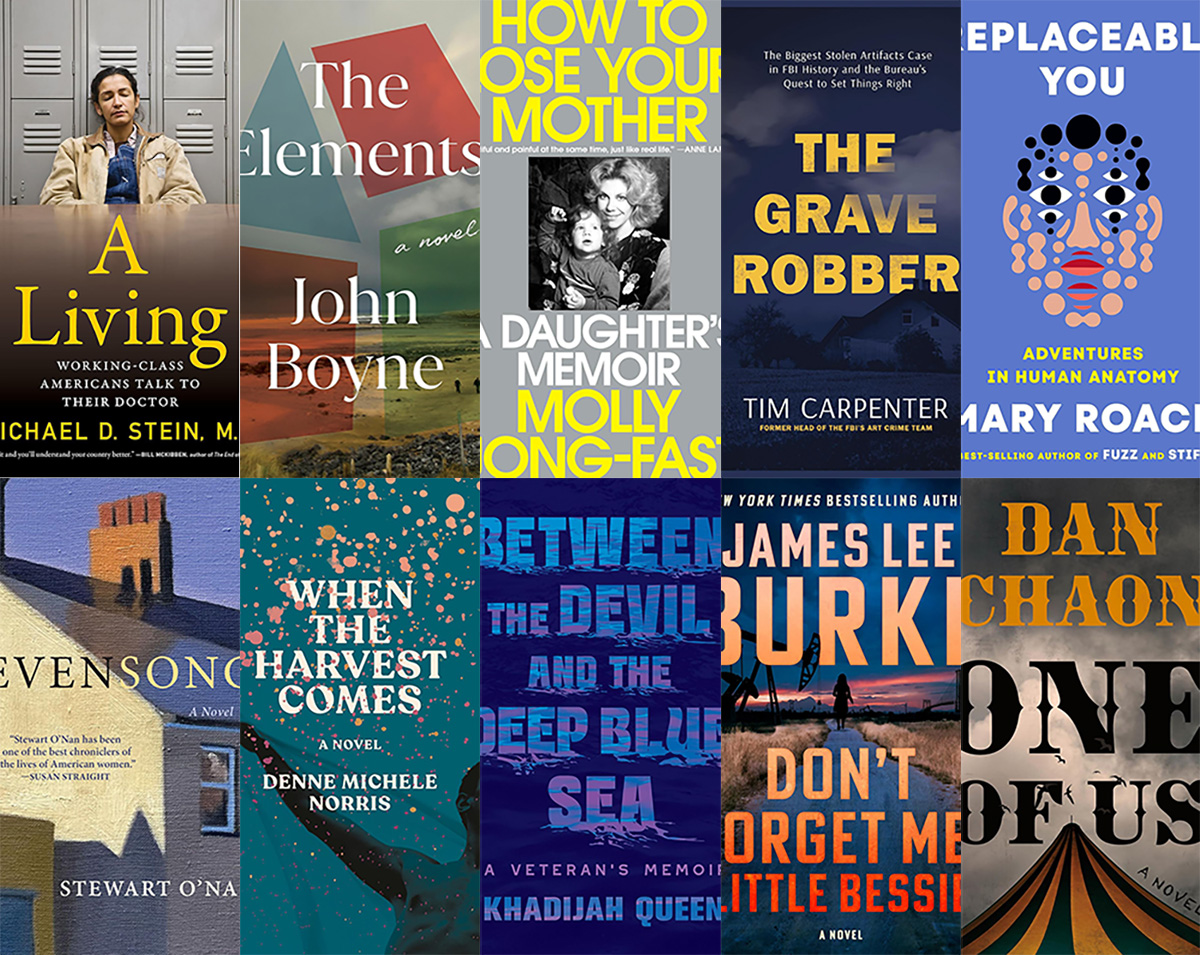

This past year, you’ve often had to make do.

Saving money here, resources there, being inventive and innovative. It’s a talent you’ve honed, but isn’t it time to have the best? Yep, so grab these Ten Best of 2025 books for your new year pleasures.

Nonfiction

Health care is on everyone’s mind now, and “A Living: Working-Class Americans Talk to Their Doctor” by Michael D. Stein, M.D. (Melville House, $26.99) lets you peek into health care from the point of view of a doctor who treats “front-line workers” and those who experience poverty and homelessness. It’s shocking, an eye-opening book, a skinny, quick-to-read one that needs to be read now.

If you’ve been doing eldercare or caring for any loved one, then “How to Lose Your Mother: A Daughter’s Memoir” by Molly Jong-Fast (Viking, $28) needs to be in your plans for the coming year. It’s a memoir, but also a biography of Jong-Fast’s mother, Erica Jong, and the story of love, illness, and living through the chaos of serious disease with humor and grace. You’ll like this book especially if you were a fan of the author’s late mother.

Another memoir you can’t miss this year is “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: A Veteran’s Memoir” by Khadijah Queen (Legacy Lit, $30.00). It’s the story of one woman’s determination to get out of poverty and get an education, and to keep her head above water while she goes below water by joining the U.S. Navy. This is a story that will keep you glued to your seat, all the way through.

Self-improvement is something you might think about tackling in the new year, and “Replaceable You: Adventures in Human Anatomy” by Mary Roach (W.W. Norton & Company, $28.99) is a lighthearted – yet real and informative – look at the things inside and outside your body that can be replaced or changed. New nose job? Transplant, new dental work? Learn how you can become the Bionic Person in real life, and laugh while you’re doing it.

The science lover inside you will want to read “The Grave Robber: The Biggest Stolen Artifacts Case in FBI History and the Bureau’s Quest to Set Things Right” by Tim Carpenter (Harper Horizon, $29.99). A history lover will also want it, as will anyone with a craving for true crime, memoir, FBI procedural books, and travel books. It’s the story of a man who spent his life stealing objects from graves around the world, and an FBI agent’s obsession with securing the objects and returning them. It’s a fascinating read, with just a little bit of gruesome thrown in for fun.

Fiction

Speaking of a little bit of scariness, “Don’t Forget Me, Little Bessie” by James Lee Burke (Atlantic Monthly Press, $28) is the story of a girl named Bessie and her involvement with a cloven-hooved being who dogs her all her life. Set in still-wild south Texas, it’s a little bit western, part paranormal, and completely full of enjoyment.

“Evensong” by Stewart O’Nan (Atlantic Monthly Press, $28) is a layered novel of women’s friendships as they age together and support one another. The characters are warm and funny, there are a few times when your heart will sit in your throat, and you won’t be sorry you read it. It’s just plain irresistible.

If you need a dark tale for what’s left of a dark winter season, then “One of Us” by Dan Chaon (Henry Holt, $28), it it. It’s the story of twins who become orphaned when their Mama dies, ending up with a man who owns a traveling freak show, and who promises to care for them. But they can’t ever forget that a nefarious con man is looking for them; those kids can talk to one another without saying a word, and he’s going to make lots of money off them. This is a sharp, clever novel that fans of the “circus” genre shouldn’t miss.

“When the Harvest Comes” by Denne Michele Norris (Random House, $28) is a wonderful romance, a boy-meets-boy with a little spice and a lot of strife. Davis loves Everett but as their wedding day draws near, doubts begin to creep in. There’s homophobia on both sides of their families, and no small amount of racism. Beware that there’s some light explicitness in this book, but if you love a good love story, you’ll love this.

Another layered tale you’ll enjoy is “The Elements” by John Boyne (Henry Holt, $29.99), a twisty bunch of short stories that connect in a series of arcs that begin on an island near Dublin. It’s about love, death, revenge, and horror, a little like The Twilight Zone, but without the paranormal. You won’t want to put down, so be warned.

If you need more ideas, head to your local library or bookstore and ask the staff there for their favorite reads of 2025. They’ll fill your book bag and your new year with goodness.

Season’s readings!

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

This gay author sees dead people

‘Are You There Spirit? It’s Me, Travis’

By Travis Holp

c.2025, Spiegel and Grau

$28/240 pages

Your dad sent you a penny the other day, minted in his birth year.

They say pennies from heaven are a sign of some sort, and that makes sense: You’ve been thinking about him a lot lately. Some might scoff, but the idea that a lost loved one is trying to tell you he’s OK is comforting. So read the new book, “Are You There, Spirit? It’s Me, Travis” by Travis Holp, and keep your eyes open.

Ever since he was a young boy growing up just outside Dayton, Ohio, Travis Holp wanted to be a writer. He also wanted to say that he was gay but his conservative parents believed his gayness was some sort of phase. That, and bullying made him hide who he was.

He also had to hide his nascent ability to communicate with people who had died, through an entity he calls “Spirit.” Eventually, though it left him with psychological scars and a drinking problem he’s since overcome, Holp was finally able to talk about his gayness and reveal his otherworldly ability.

Getting some people to believe that he speaks to the dead is still a tall order. Spirit helps naysayers, as well as Holp himself.

Spirit, he says, isn’t a person or an essence; Spirit is love. Spirit is a conduit of healing and energy, speaking through Holp in symbolic messages, feelings, and through synchronistic events. For example, Holp says coincidences are not coincidental; they’re ways for loved ones to convey messages of healing and energy.

To tap into your own healing Spirit, Holp says to trust yourself when you think you’ve received a healing message. Ignore your ego, but listen to your inner voice. Remember that Spirit won’t work on any fixed timeline, and its only purpose is to exist.

And keep in mind that “anything is possible because you are an unlimited being.”

You’re going to want very much to like “Are You There, Spirit? It’s Me, Travis.” The cover photo of author Travis Holp will make you smile. Alas, what you’ll find in here is hard to read, not due to content but for lack of focus.

What’s inside this book is scattered and repetitious. Love, energy, healing, faith, and fear are words that are used often – so often, in fact, that many pages feel like they’ve been recycled, or like you’ve entered a time warp that moves you backward, page-wise. Yes, there are uplifting accounts of readings that Holp has done with clients here, and they’re exciting but there are too few of them. When you find them, you’ll love them. They may make you cry. They’re exactly what you need, if you grieve. Just not enough.

This isn’t a terrible book, but its audience might be narrow. It absolutely needs more stories, less sentiment; more tales, less transcendence and if that’s your aim, go elsewhere. But if your soul cries for comfort after loss, “Are You There, Spirit? It’s Me, Travis” might still make sense.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

-

Colombia5 days ago

Colombia5 days agoGay Venezuelan man who fled to Colombia uncertain about homeland’s future

-

Arts & Entertainment5 days ago

Arts & Entertainment5 days ago2026 Most Eligible LGBTQ Singles nominations

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoKennedy Center renaming triggers backlash

-

District of Columbia5 days ago

District of Columbia5 days agoNew interim D.C. police chief played lead role in security for WorldPride