Arts & Entertainment

Queer, Crip and Here: Meet blind writer Caitlin Hernandez

Author navigates intersecting identities in life, work

(Editor’s Note: One in four people in America has a disability, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Queer and disabled people have long been a vital part of the LGBTQ+ community. Take two of the many queer history icons who were disabled: Michelangelo is believed to have been autistic. Marsha P. Johnson, who played a heroic role in the Stonewall Uprising, had physical and psychiatric disabilities. Today, Deaf/Blind fantasy writer Elsa Sjunneson; actor and bilateral amputee Eric Graise who played Marvin in the “Queer as Folk” reboot; and Kathy Martinez, a blind, Latinx lesbian, Assistant Secretary of Labor for Disability Employment Policy for the Obama administration, are only a few of the queer and disabled people in the LGBTQ community. Yet, the stories of this vital segment of the queer community have rarely been told. In its monthly, yearlong series, “Queer, Crip and Here,” the Blade will tell some of these un-heard stories.)

Some creators agonize for years before plunging into their art.

This wasn’t the case with queer, blind writer and teacher Caitlin Hernandez. Hernandez wrote her first “novel,” “Computer Whiz,” she writes in her bio, when she was in the fourth grade. She kept her monitor off so no one would see her “masterpiece.”

Reading and writing have been a part of Hernandez’s life for as long as she can remember. “I was writing, even as a little kid,” Hernandez, who was born in 1990 and grew up in Danville, Calif., said in a telephone interview with the Blade, “In first grade, I wrote stories in braille. They taught me to type. Because people were having to translate.”

As a kid, Hernandez used a tape recorder to tell stories. “That happens so often with blind kids,” said Hernandez, who lives in San Francisco with her partner Martha and Maite their Rottweiler.

Maite was Martha’s dog when the couple got together. “I call her my ‘stepdogter,’” Hernandez said. It’s clear from the get-go that she doesn’t take herself too seriously. Maite, her “stepdogter,” is “currently writing a picture book,” Hernandez jokes in her bio.

It’s commonly thought that disabled people lead sad, tragic lives. But Hernandez busts this myth. Martha, her partner, “reads braille with her eyes,” Hernandez whimsically writes in her bio.

Hernandez is committed to teaching and writing. But, she “loves eating coffee ice cream, watching Star Trek Voyager, singing, skipping and using her rainbow cane – sometimes all at once,” Hernandez writes in her bio.

Queerness is an integral part of Hernandez’s life: from her fiction, which tells stories of LGBTQ people, disabled people, and people of color to her rainbow cane.

“Queerness is considered cool now in many places,” Hernandez said, “it’s normalized.”

But that’s not true with disability, she added. “Generally, there’s more fear and misperceptions around disabled people,” Hernandez said.

Because of their discomfort with disabled people, she’s often left alone at social and literary gatherings.

“Because I’m blind, people frequently won’t talk to me,” Hernandez said, “even if I’ve read at an open mic.”

To make people feel more comfortable with her, Hernandez, totally blind since birth, sometimes uses a rainbow cane. “I designed it,” she said, “it has the colors of the rainbow flag. If you’re queer, you’ll get that.”

But it’s also beautiful because it’s a rainbow, Hernandez said, “It’s a great ice-breaker.”

(Hernandez uses her rainbow cane when she’s out with friends. When traveling by herself, she uses the white cane used by most blind people.)

Once people get to know [disabled people],” Hernandez said, “they’re chill with us.”

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), a landmark civil rights law, despite problems of enforcement and compliance, has done much to change life for disabled people.

The ADA generation (those born when or after the law was passed) has grown up with the expectation that disabled people have rights. They’re not surprised to see curb cuts or braille menus. They expect employers to make accommodations for disabled employees and hospitals to have sign language interpreters for Deaf people.

Yet despite the ADA, ableism persists (even within her own ADA generation), Hernandez said. A key reason why discomfort with and fear of disabled people is still so pervasive is the problem of representation, she said.

Hernandez, a Lambda Literary Emerging Writer Fellow in 2015 and 2018, is acutely aware of how disabled and queer and disabled people are portrayed in fiction and nonfiction.

“Our lives are often represented so badly,” Hernandez said, “often by nondisabled creators. There’s a lot of fear and inaccuracy.”

Thankfully, there are a few fab books with disabled characters by disabled authors, Hernandez said. She loves “The Kiss Quotient” by Helen Hoang, who is autistic. The novel portrays the romance of an autistic econometrician and her biracial male escort.

Hernandez is a fan of “The Silence Between us,” a young adult romance featuring a Deaf character, by hard-of-hearing author Alison Gervais.

“The Chance to Fly,” co-authored by Ali Stroker, the bisexual, Tony-winning actress who uses a wheelchair, and Stacy Davidowitz, is one of Hernandez’s faves. The book, a novel for middle-schoolers, tells the story of a theater-loving, wheelchair using girl, who defies ableist expectations.

Hernandez began to think she was queer when she was in high school. But, she didn’t come out then to anyone except a few of her friends. “They kinda didn’t believe me,” Hernandez said, “because a friend of ours had already come out as queer and they thought I was trying to copy him.”

After she was in college, Hernandez, who earned a bachelor’s degree in literature from the University of California, Santa Cruz in 2012, came out to her parents.

Her folks, now divorced, were fine with her being queer.

Because nondisabled people frequently don’t see disabled people as datable or sexy, some aspects of coming out are more difficult if you have a disability, Hernandez said. “We often miss one of the rites of passage of coming out,” she said, “of saying ‘I am queer – here with my queer date (or partner).’”

Hernandez’s first relationship was with a woman who was closeted. “We couldn’t be out,” she said.

Hernandez got together with her partner Martha in November 2019. Then there was the pandemic and everything was cancelled. “So we didn’t get to go out as an out queer couple,” Hernandez said.

“Everybody knows I’m partnered with Martha,” she added.

But because of ableism, sometimes people don’t see her as Martha’s romantic partner, Hernandez said.

Like many, Hernandez navigates intersecting identities. “I’m thinking more about my being of mixed race,” Hernandez said, “My Mom is white. My Dad is one-half Mexican and one-half German. I can pass as white,” she added.

She’s grappling with what it means to have a Latinx last name, Hernandez said.

She wishes she had taken Spanish. “But I took French,” Hernandez said, “I wanted to do what my friends were doing.”

As a writer, Hernandez hopes to help children who live with intersecting identities.

Her work has appeared in “Aromatica Poetica,” “Wordgathering” and in “Barriers and Belonging,” “Firsts: Coming Of Age Stories by People with Disabilities” and other anthologies.

In 2013, “Dreaming in Color,” a musical written by Hernandez, was produced by CRE Outreach at the Promenade Playhouse in Santa Monica, Calif.

Hernandez’s unpublished young adult novel “Even Touch Has a Tune” is about a queer, blind girl falling in love with another girl and surviving sexual assault, Hernandez said in an email to the Blade. “It’s fiction but has a lot of autobiographical content,” she added.

If you’re disabled, you’re more vulnerable to sexual assault. When she was a freshman, Hernandez became friends with a fully sighted guy who she’d met in her classes. “He seemed nice,” she said, “but then he came over and touched me inappropriately.”

“I froze up,” Hernandez added, “if you’re disabled, you’re vulnerable. You’re taught to be polite – to keep quiet.”

While there’s more representation of disabled people in fiction, Hernandez is still discouraged.

Because of ableism, many literary agents may not want her “disabled and assault novel,” Hernandez said. (Her unpublished YA novel “Even Touch Has a Tune” is represented by Emily Keyes of Keyes Agency.)

Too frequently, representation of disabled people is focused on ableist tropes like “inspiration porn” and “overcoming,” Hernandez said. There isn’t interest in portraying scary, difficult aspects (like sexual assaults) of disabled people’s lives, she added.

But discouragement doesn’t stop Hernandez from writing or from connecting with kids as a teacher.

Hernandez earned a master’s degree in special education and her teaching credentials from San Francisco State University in 2016. Today, she is a resource specialist with the San Francisco Unified School District.

Hernandez enjoys forging a connection with disabled and nondisabled students. “Nondisabled kids come to me for extra help,” she said.

Hernandez has accomplished much. But, “I’ve learned I don’t have to be a role model,” she said, “I don’t have to be perfect.”

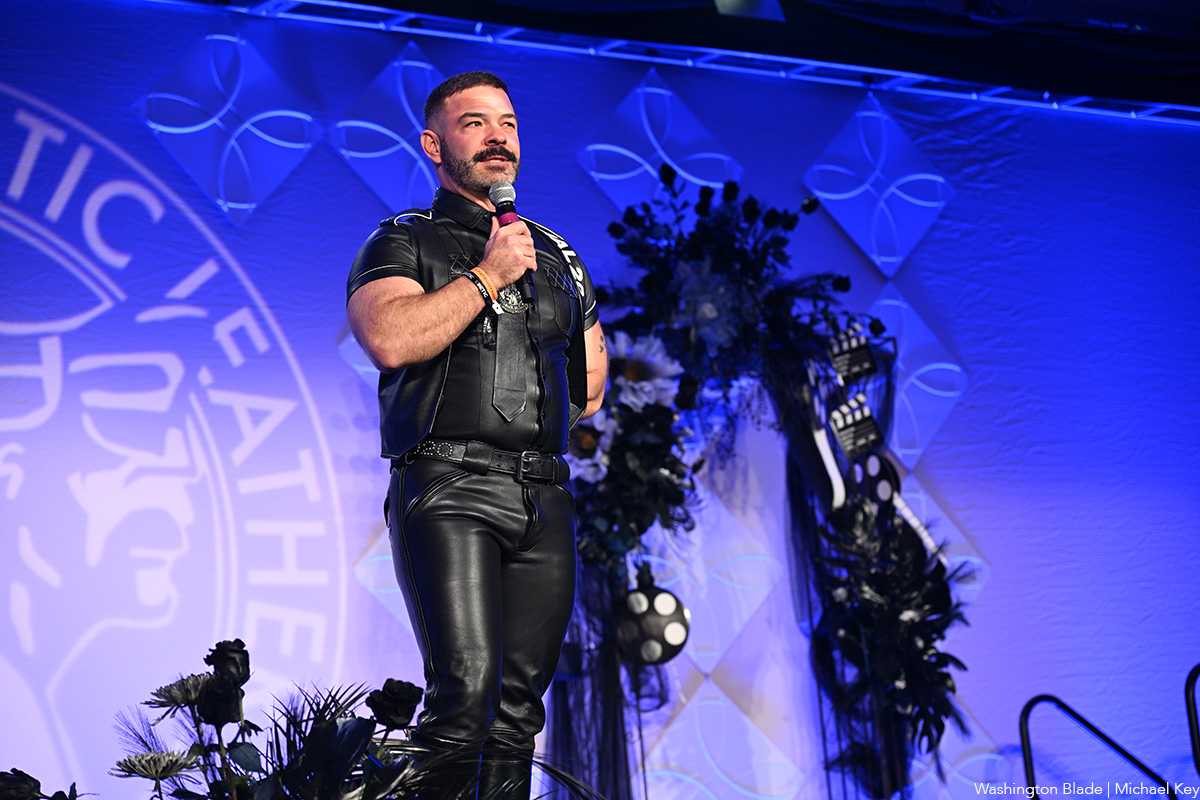

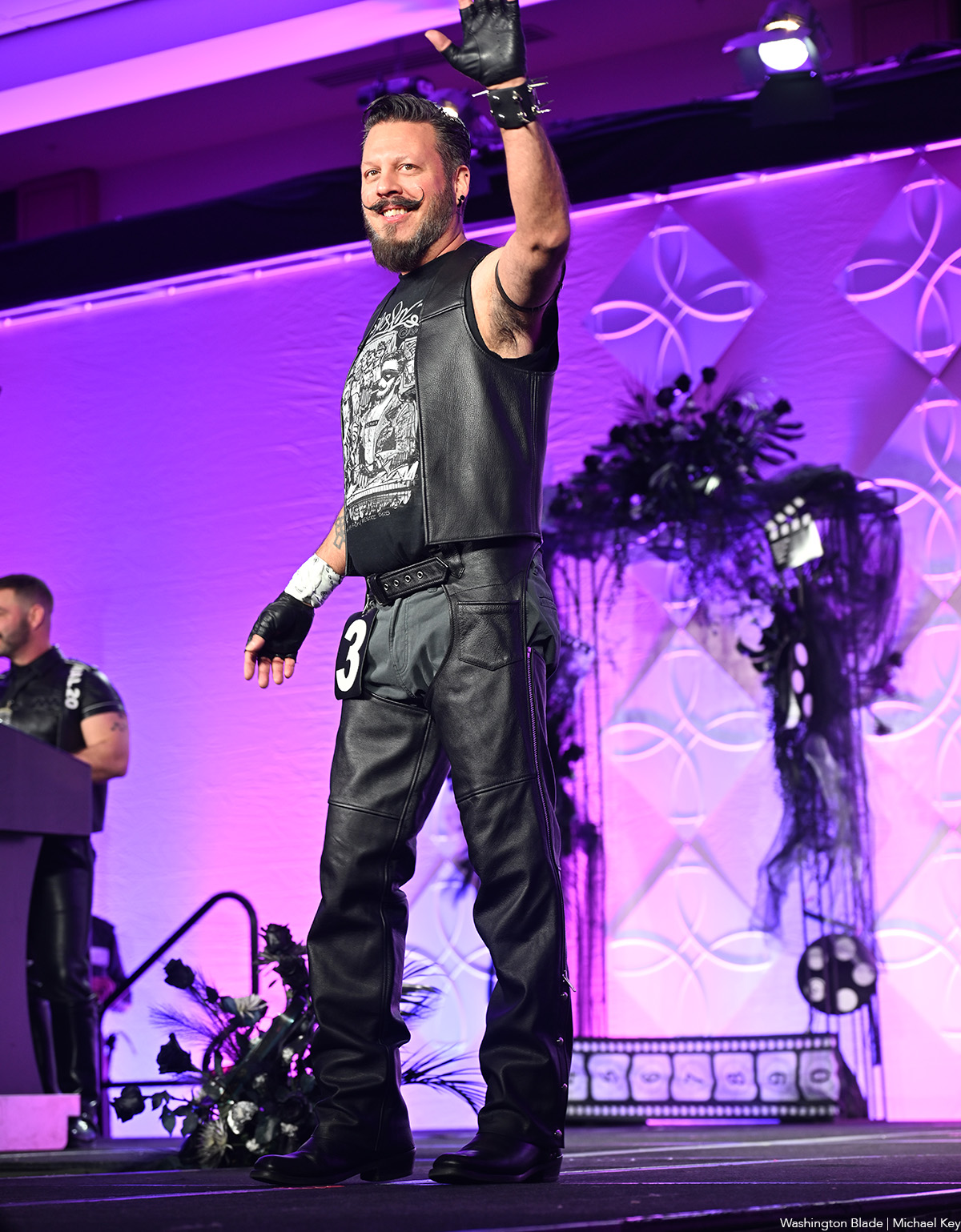

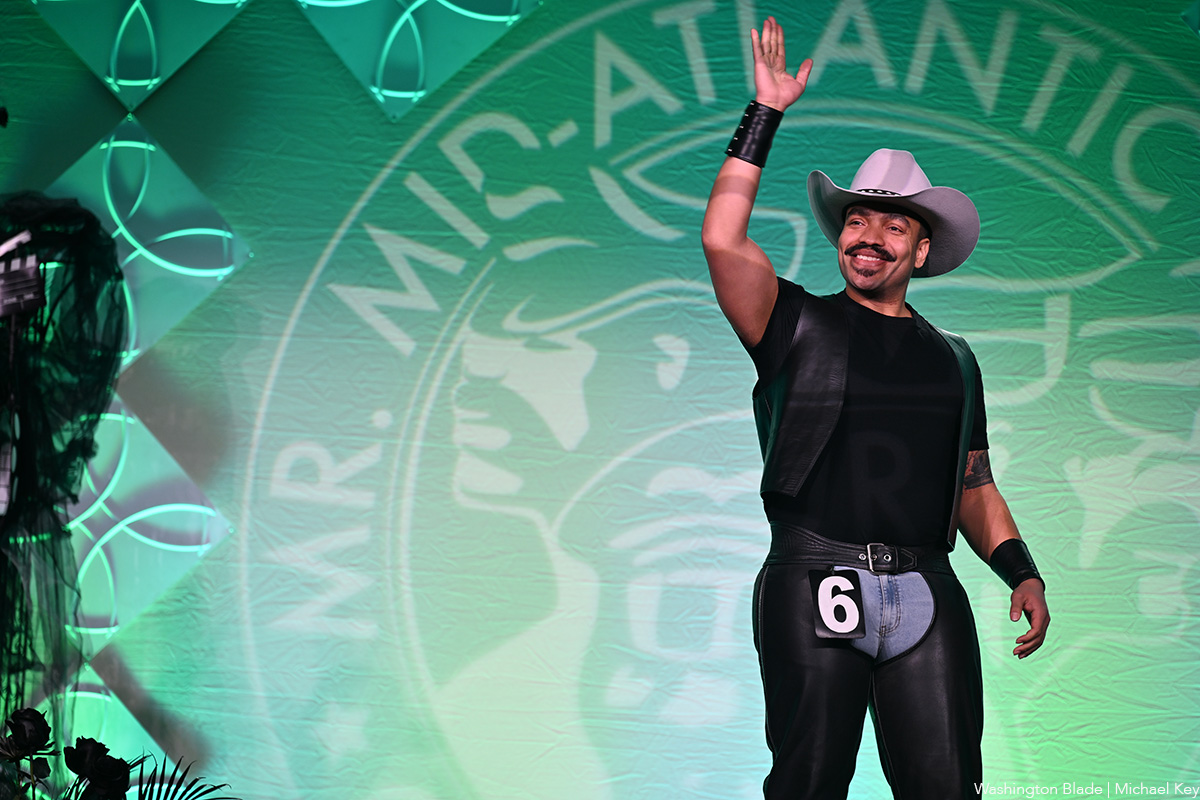

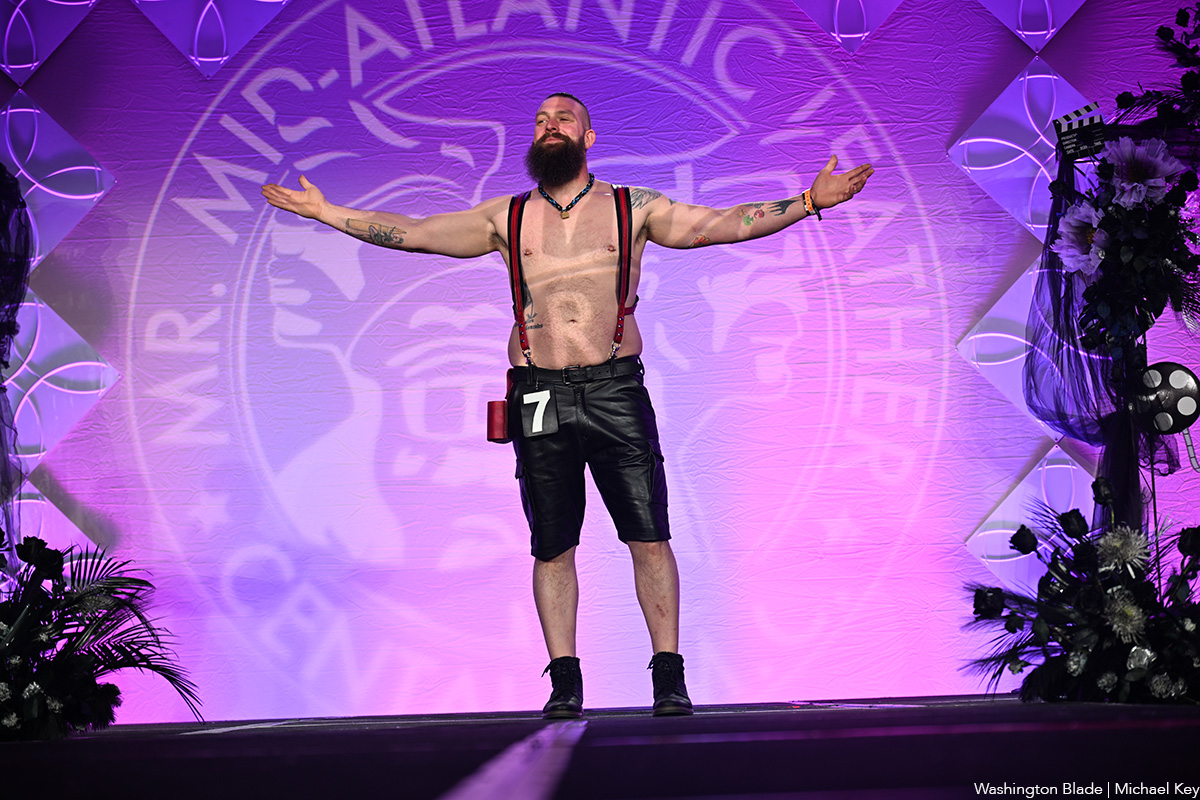

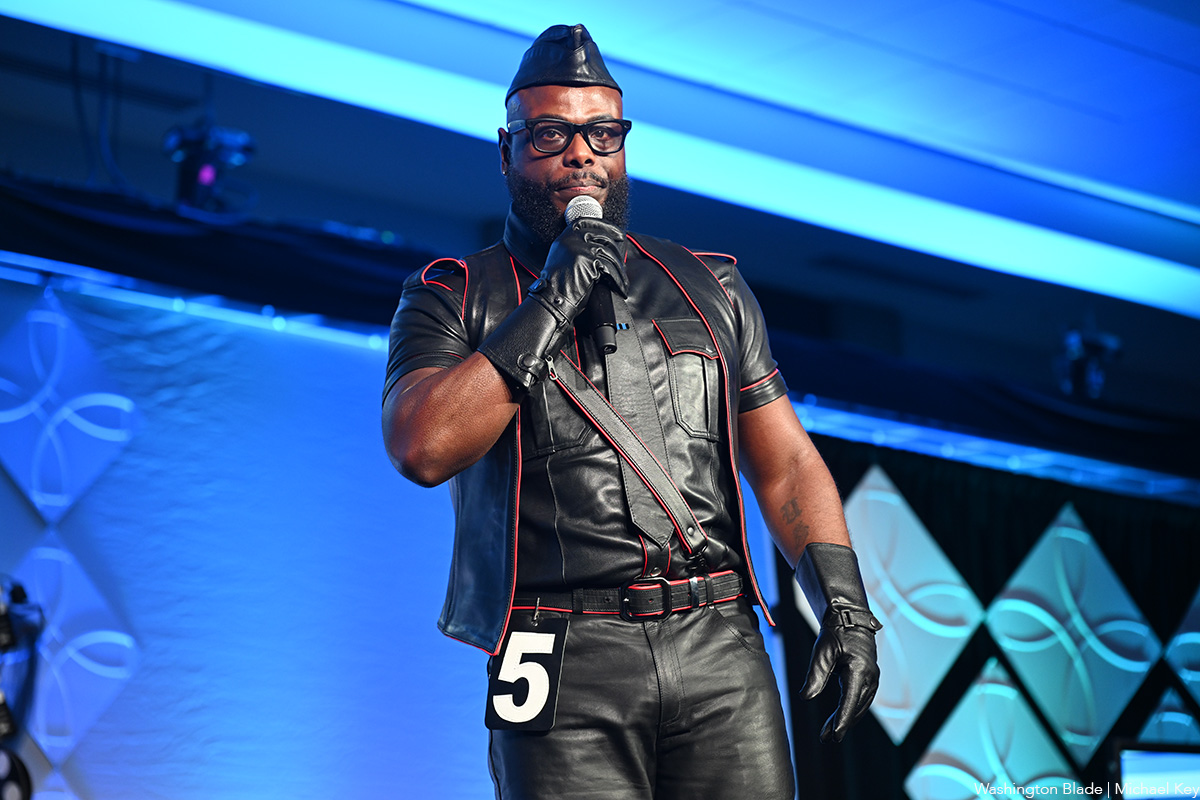

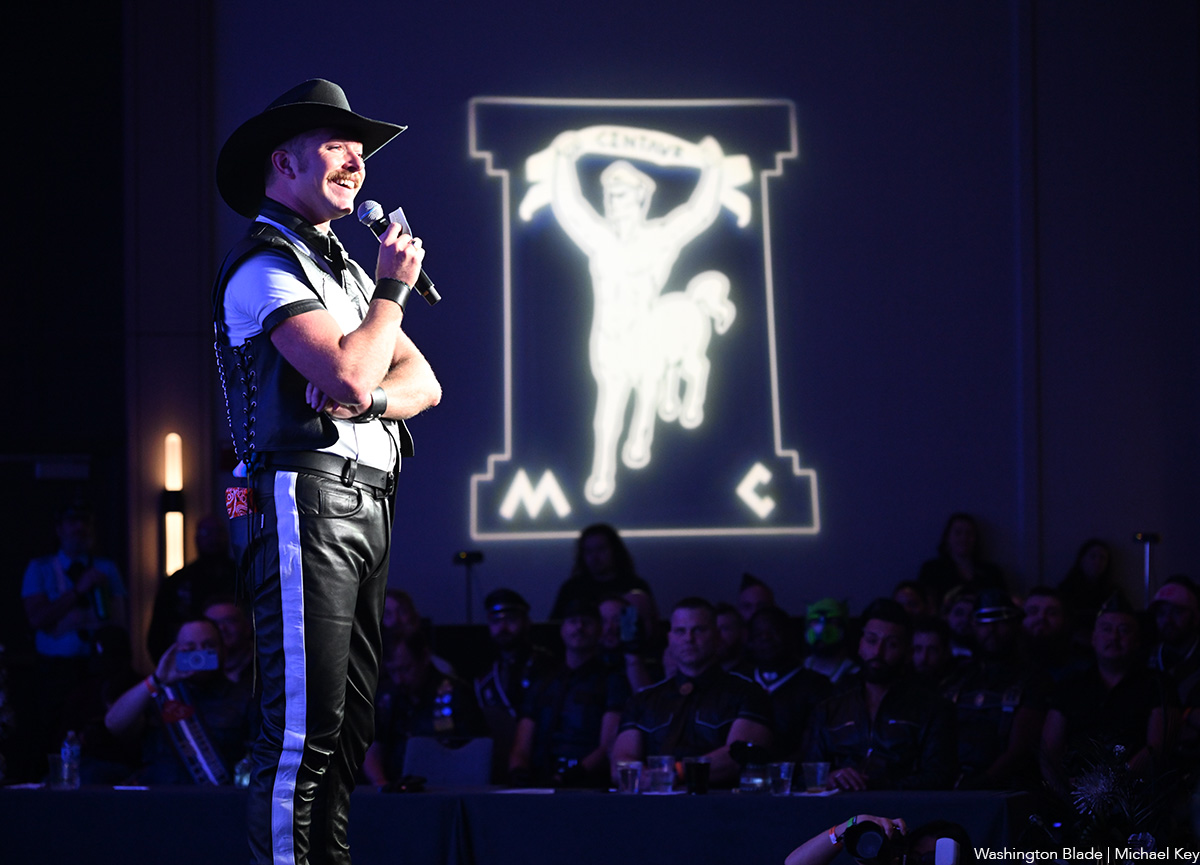

The 2026 Mr. Mid-Atlantic Leather competition was held at the Hyatt Regency Capitol Hill on Sunday. Seven contestants vied for the title and Gage Ryder was named the winner.

(Washington Blade photo by Michael Key)

Theater

Voiceless ‘Antony & Cleopatra’ a spectacle of operatic proportions

Synetic production pulls audience into grips of doomed lovers’ passion

‘Antony & Cleopatra’

Through Jan. 25

Synetic Theater at

Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Klein Theatre

450 7th St., N.W.

Synetictheater.org

A spectacle of operatic proportions, Synetic Theater’s “Antony & Cleopatra” is performed entirely voiceless. An adaptation of the Bard’s original (a play bursting with wordplay, metaphors, and poetic language), the celebrated company’s production doesn’t flinch before the challenge.

Staged by Paata Tsikurishvili and choreographed by Irina Tsikurishvili, this worthy remount is currently playing at Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Klein Theatre, the same venue where it premiered 10 years ago. Much is changed, including players, but the usual inimitable Synectic energy and ingenuity remain intact.

As audiences file into the Klein, they’re met with a monumental pyramid bathed in mist on a dimly lit stage. As the lights rise, the struggle kicks off: Cleopatra (Irina Kavsadze) and brother Ptolemy (Natan-Maël Gray) are each vying for the crown of Egypt. Alas, he wins and she’s banished from Alexandria along with her ethereal black-clad sidekick Mardian (Stella Bunch); but as history tells us, Cleopatra soon makes a triumphant return rolled in a carpet.

Meanwhile, in the increasingly dangerous Rome, Caesar (memorably played by Tony Amante) is assassinated by a group of senators. Here, his legendary Ides of March murder is rather elegantly achieved by silver masked politicians, leaving the epic storytelling to focus on the titular lovers.

The fabled couple is intense. As the Roman general Antony, Vato Tsikurishvili comes across as equal parts warrior, careerist, and beguiled lover. And despite a dose of earthiness, it’s clear that Kavsadze’s Cleopatra was born to be queen.

Phil Charlwood’s scenic design along with Colin K. Bills’ lighting cleverly morph the huge pyramidic structure into the throne of Egypt, the Roman Senate, and most astonishingly as a battle galley crashing across the seas with Tsikurishvili’s Antony ferociously at the helm.

There are some less subtle suggestions of location and empire building in the form of outsized cardboard puzzle pieces depicting the Mediterranean and a royal throne broken into jagged halves, and the back-and-forth of missives.

Of course, going wordless has its challenges. Kindly, Synectic provides a compact synopsis of the story. I’d recommend coming early and studying that page. With changing locations, lots of who’s who, shifting alliances, numerous war skirmishes, and lack of dialogue, it helps to get a jump on plot and characters.

Erik Teague’s terrific costume design is not only inspired but also helpful. Crimson red, silver, and white say Rome; while all things Egyptian have a more exotic look with lots of gold and diaphanous veils, etc.

When Synetic’s voicelessness works, it’s masterful. Many hands create the magic: There’s the direction, choreography, design, and the outrageously committed, sinewy built players who bring it to life through movement, some acrobatics, and the remarkable sword dancing using (actual sparking sabers) while twirling to original music composed by Konstantine Lortkipanidze.

Amid the tumultuous relationships and frequent battling (fight choreography compliments of Ben Cunis), moments of whimsy and humor aren’t unwelcome. Ptolemy has a few clownish bits as Cleopatra’s lesser sibling. And Antony’s powerful rival Octavian (ageless out actor Philip Fletcher) engages in peppy propaganda featuring a faux Cleopatra (played by Maryam Najafzada) as a less than virtuous queen enthusiastically engaged in an all-out sex romp.

When Antony and Cleopatra reach their respective ends with sword and adder, it comes almost as a relief. They’ve been through so much. And from start to finish, without uttering a word, Kavsadze and Tsikurishvili share a chemistry that pulls the audience into the grips of the doomed lovers’ palpable passion.

Out & About

Love board games and looking for love?

Quirk Events will host “Board Game Speed Dating for Gay Men” on Thursday, Jan. 22 at 7 p.m. at KBird DC.

Searching for a partner can be challenging. But board games are always fun. So what if you combined board games and finding a partner?

Picture this: You sit down for a night of games. A gaming concierge walks you through several games over the course of the night. You play classics you love and discover brand new games you’ve never heard of, playing each with a different group of fun singles. All while in a great establishment.

At the end of the night, you give your gaming concierge a list of the folks you met that you’d like to date and a list of those you met that you’d like to just hang out with as friends. If any two people put down the same name as each other in either column, then your gaming concierge will make sure you get each other’s e-mail address and you can coordinate a time to hang out.

Tickets cost $31.80 and can be purchased on Eventbrite.