Arts & Entertainment

SMYAL set to celebrate 40th anniversary

D.C. LGBTQ youth advocacy group remains focused on the future

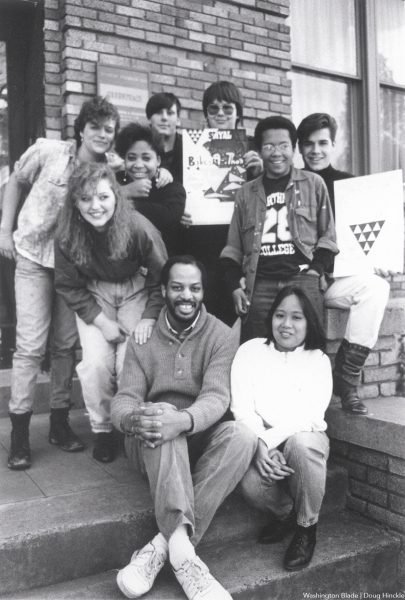

Founded in 1984 by a small group of volunteer gay and lesbian activists who recognized the need for a safe place for LGBTQ youth to meet and receive support, the group SMYAL has evolved over the past 40 years into one of the nation’s largest organizations providing a wide range of support, including housing and mental health counseling, for LGBTQ youth in the D.C. metro area.

SMYAL’s work over its 40-year history and its plans for the future were expected to be highlighted and celebrated at its annual fundraising brunch scheduled for Saturday, Sept. 21 at D.C.’s Marriott Marquis Hotel. SMYAL says the event will be hosted by a “star-studded group,” including MSNBC’s Jonathan Capehart.

“What a profound moment and opportunity to be able to be here while celebrating the 40th anniversary,” said Erin Whelan, who began her role as SMYAL’s executive director in September 2022. “It’s an exciting time for us,” Whelan told the Blade in a Sept. 11 interview along with SMYAL’s Director of Communications Hancie Stokes.

“We just finished a strategic plan,” Whelan said. “Not only are we reflecting on the previous 40 years but really looking to the next three to five years,” she said, adding that the plan calls for continuing SMYAL’s growth, which accelerated over the past four or five years.

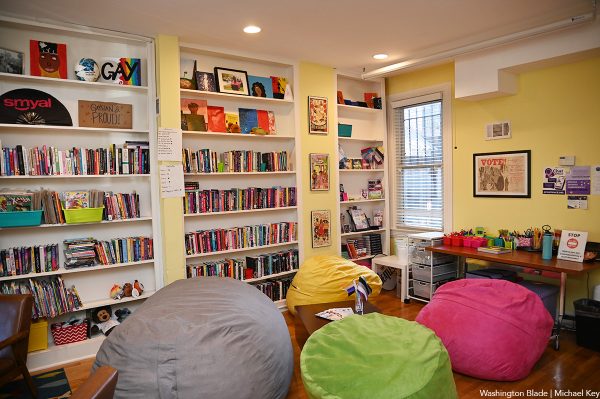

Whelan and Stokes spoke with the Washington Blade at SMYAL’s headquarters and LGBTQ youth drop-in center in the Capitol Hill neighborhood. SMYAL’s ability to purchase that building in 1997 through financial support from the community, has played an important role in SMYAL’s history, according to Whelan and Stokes.

The two-story building consists of two attached row houses that it has converted into offices and meeting space.

The two pointed to information posted on the SMYAL website, including information from D.C.’s Rainbow History Project, which tells the story of SMYAL’s founding in 1984. It was a time when many LGBTQ youth faced hardship and discrimination as well as challenges from their families, some of whom were unaccepting of their kids who thought about identifying as gay, lesbian or gender nonconforming.

Local gay activist and attorney Bart Church, one of SMYAL’s co-founders, told fellow activists that he was prompted to help launch an LGBTQ youth advocacy group after learning that gender nonconforming youth, including some who “crossed dressed” and identified as a gender other than their birth gender, were being incarcerated in D.C.’s St. Elizabeth’s psychiatric hospital.

“Recognizing that that these young people were not mentally ill, but instead needed programs that were safe and affirming to explore their identities, Bart and several other allied community members formed a group called SMYAL,” a statement released by SMYAL says. It says Church and other founders named the group the Sexual Minority Youth Assistance League.

“We met at first at Bart’s apartment,” said another co-founder, Joe Izzo, who later worked for many years as a mental health counselor at D.C.’s Whitman-Walker Clinic. In addition to the incarceration of some of the youth at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Izzo said the SMYAL founders were concerned about the impact of the AIDS epidemic on gay youth, who may not have been informed about safer sex practices.

D.C. gay activist and economist Chuck Goldfarb, who said he became involved as a SMYAL volunteer in 1986, said he recalls hearing from gay and lesbian social workers who also became involved with SMYAL “that a number of youths who were, in the term they used, cross dressing, were getting locked up in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital psychiatric ward.”

“And Bart Church called together people he knew were service providers and said let’s get together and do something about it,” Goldard told the Blade. “And the first thing they started doing was to put together a referral list of LGBT supportive therapists and counselors,” according to Goldfarb, who could be called to help LGBT youth, and their families address issues such as sexual orientation and gender identity.

Among the original group of founders credited with helping to transform SMYAL into a larger, more comprehensive organization was Stephan Wade, who developed a training program and led a needs assessment effort. The assessment, among other things, determined that what LGBT youth at that time most needed was a safe place to meet and socialize with others like themselves, the SMYAL write-up says.

“Within three years, SMYAL established a well-respected program of youth socialization and education as well as a training program for adult professionals, with outreach to schools, runaway shelters, and juvenile correctional facilities,” the write-up says. “Many individuals contributed to the SMYAL program, but it was Stephan Wade’s expertise and leadership that turned a plan into reality,” it says. The write-up says Wade died of AIDS-related complications in 1995.

With Wade and his fellow volunteers putting in place SMYAL’s first drop-in center for LGBTQ youth and the other programs supported by volunteer counselors and other professionals, SMYAL hired its first full-time staff member in 1989, the write-up says.

Stokes points out that SMYAL drew considerable media attention in 1990 when vocal opposition surfaced to ads SMYAL had placed in high school newspapers announcing its services for LGBT youth, which were initially approved by school officials. The opposition, coming from some parents and conservative advocates opposed to LGBTQ rights, in the long run may have generated attention to SMYAL and its programs that prompted others to support SMYAL including financially.

The SMYAL write-up says the first annual fundraising brunch, which is the organization’s largest fundraising event, began in 2003. Stokes said in the following years SMYAL has received support from local foundations and through a major individual donor program as well as from grants from the D.C. government that support specific SMYAL programs.

Stokes and Whelan also point out that in 2013 SMYAL changed its name from Sexual Minority Youth Assistance League to Supporting and Mentoring Youth Advocates and Leaders, which kept the SMYAL initials. The two said the change reflects SMYAL’s significant expansion of its services beyond its initial core program of providing a safe meeting space for LGBTQ youth.

The two note that in 2017 SMYAL began its housing program for homeless LGBTQ youth; in 2019 it launched its Little SMYALs program, which provides services for youth between the ages of 6 and 12 and their families. And in 2021 SMYAL launched its Clinical Services program, which provides mental health counseling for LGBTQ youth.

Stokes and Whelan said the Little SMYALs program involves parents bringing in their kids mostly to a Saturday gathering where the kids meet, socialize, and play games or do artwork. The two said in the age range of 6 to 12, the Little SMYALers, as they are called, are mostly dealing with their gender identity rather than sexual orientation.

“Kids are expressing to their parents or caregivers that they might feel different,” Whelan said. “Often times that’s expressing that they don’t feel like they are the gender in which they were born. And so, the parents are starting to talk with that youth about what that is.”

Stokes said the Little SMYALs program reaches out to parents as well as the youth. “How do we equip parents to be there to support and believe them when they come out,” is a question that Stokes said SMYAL tries to address. “How do you make sure you are a safe resource when your young person comes to you and says this is who I am? We want people to see you fully and authentically.”

Stokes and Whelan said SMYAL currently has a staff of about 43 and an annual budget of $5.1 million. They said about 90 families are currently enrolled in the Little SMYALs program, with about 30 families with their kids attending on a monthly basis. They said the youth ages 13 through high school age come at least twice a week after school hours and on Saturdays.

“And they do all sorts of things from sharing, just talking, listening to music, eating, and just being in community with each other,” Whelan said of the older kids. Stokes noted that SMYAL also organizes events for the older youth, including a Pride Prom for youth “who might not feel comfortable bringing their partner of choice to their school’s prom.”

The two said SMYAL also organizes an annual activist summit for youth interested in becoming leaders and organizers. They said about 90 youth attended this year’s summit.

“I think one thing that I’m really proud of is that we started as a grassroots organization out of a need in our community,” Whelan said. “And I think through the 40 years that we’ve been in existence, we continue to really anchor in what are the most pressing needs of our communities,” she said.

Further information about SMYAL’s programs and the upcoming brunch can be accessed at smyal.org.

Movies

Rise of Chalamet continues in ‘Marty Supreme’

But subtext of ‘American Exceptionalism’ sparks online debate

Casting is everything when it comes to making a movie. There’s a certain alchemy that happens when an actor and character are perfectly matched, blurring the lines of identity so that they seem to become one and the same. In some cases, the movie itself feels to us as if it could not exist without that person, that performance.

“Marty Supreme” is just such a movie. Whatever else can be said about Josh Safdie’s wild ride of a sports comedy – now in theaters and already racking up awards – it has accomplished exactly that rare magic, because the title character might very well be the role that Timothée Chalamet was born to play.

Loosely based on real-life table tennis pro Marty Reisman, who published his memoir “The Money Player” in 1974, this Marty (whose real surname is Mauser) is a first-generation American, a son of Jewish immigrant parents in post-WWII New York who works as a shoe salesman at his uncle’s store on the Lower East Side while building his reputation as a competitive table tennis player in his time off. Cocky, charismatic, and driven by dreams of championship, everything else in his life – including his childhood friend Rachel (Odessa A’zion), who is pregnant with his baby despite being married to someone else – takes a back seat as he attempts to make them come true, hustling every step of the way.

Inevitably, his determination to win leads him to cross a few ethical lines as he goes – such as stealing money for travel expenses, seducing a retired movie star (Gwyneth Paltrow), wooing her CEO husband (Kevin O’Leary) to sponsor him, and running afoul of the neighborhood mob boss (veteran filmmaker Abel Ferrara) – and a chain of consequences piles at his heels, threatening to undermine his success before it even has a chance to happen.

Filmed in 35mm and drenched in the visual style of the gritty-but-gorgeous “New Hollywood” cinema that Safdie – making his solo directorial debut without the collaboration of his brother Benny – so clearly seeks to evoke, “Marty Supreme” calls up unavoidable connections to the films of that era with its focus on an anti-hero protagonist trying to beat the system at its own game, as well as a kind of cynical amorality that somehow comes across more like a countercultural call-to-arms than a nihilistic social commentary. It’s a movie that feels much more challenging in the mid-2020s than it might have four or so decades ago, building its narrative around an ego-driven character who triggers all our contemporary progressive disdain; self-centered, reckless, and single-mindedly committed to attaining his own goals without regard for the collateral damage he inflicts on others in the process, he might easily – and perhaps justifiably – be branded as a classic example of the toxic male narcissist.

Yet to see him this way feels simplistic and reductive, a snap value judgment that ignores the context of time and place while invoking the kind of ethical purity that can easily blind us to the nuances of human behavior. After all, a flawed character is always much more authentic than a perfect one, and Marty Mauser is definitely flawed.

Yet in Chalamet’s hands, those flaws become the heart of a story that emphasizes a will to transcend the boundaries imposed by the circumstantial influences of class, ethnicity, and socially mandated hierarchy. His Marty is a person forging an escape path in a world that expects him to “know his place,” who is keenly aware of the anti-semitism and cultural conventions that keep him locked into a life of limited possibilities and who is willing to do whatever it takes to break free of them; and though he might draw our disapproval for the choices he makes, particularly with regard to his relationship with Rachel, he grows as he goes, navigating a character arc that is less interested in redemption for past sins than it is in finding the integrity to do better the next time – and frankly, that’s something that very few toxic male narcissists ever do.

In truth, it’s not surprising that Chalamet nails the part, considering that it’s the culmination of a project that began in 2018, when Safdie gave him Reisman’s book and suggested collaborating on a movie based on the story of his rise to success. The actor began training in table tennis, and continued to master it over the years, even bringing the necessary equipment to location shoots for movies like “Dune” so that he could perfect his skills – but physical skill aside, he always had what he needed to embody Marty. This is a character who knows what he’s got and is not ashamed to use it, who has the drive to succeed, the will to excel, and the confidence to be unapologetically himself while finding joy in the exercise of his talents, despite how he might be judged by those who see only ego. If any actor could be said to reflect those qualities, it’s Timothée Chalamet.

Other members of the cast also score deep impressions, especially A’zion, whose Rachel avoids tropes of victimhood to achieve her own unconventional character arc. Paltrow gives a remarkably vulnerable turn as the aging starlet who willingly allows Marty into her orbit despite the worldliness that tells her exactly what she’s getting into, while O’Leary embodies the kind of smug corporate venality that instantly positions him as the avatar for everything Marty is trying to escape. Queer fan-fave icons Fran Drescher and Sandra Bernhard also make small-but-memorable appearances, and real-life deaf table tennis player Koto Kawaguchi strikes a noble chord as the Japanese champion who becomes Marty’s de facto rival.

As for Safdie’s direction, it’s hard to find anything to criticize in his film’s visually stylish, sumptuously photographed (by Darius Khondji), and tightly paced delivery, which makes its two-and-a-half hour runtime fly by without a moment of drag.

It must be said that the screenplay – co-written by Safdie with Ronald Bronstein – leans heavily into an approach in which much of the plot hinges on implausible coincidences, ironic twists, and a general sense of orchestrated chaos that makes things occasionally feel a little too neat in the service of creating an outlandish “tall tale” narrative ; but let’s face it, life is like that sometimes, so it’s easy to overlook.

What might be more problematic, for some audiences, is Marty’s often insufferable – and occasionally downright ugly behavior. Yes, Chalamet infuses it all with humanizing authenticity, and the story is ultimately more about the character’s emotional evolution than it is about his winning at ping-pong, but it’s impossible not to read a subtext of American Exceptionalism into his winner-takes-all climb to victory – which is why “Marty Supreme,” for all its critical acclaim, is the subject of heated debate and outrage on social media right now.

As for us, we’re not condoning anything Marty does or says as he hustles his way to the winner’s circle. All we’re saying is that Timothée Chalamet has become an even better actor since he captured our attention (and a lot of gay hearts) in “Call Me By Your Name.”

And that’s saying a lot, because he was pretty great, even then.

a&e features

Visible and unapologetic: MAL brings the kink this weekend

Busy lineup includes dances, pups, super heroes, and more

MLK Weekend in D.C. brings the annual Mid-Atlantic Leather (MAL) Weekend. Just a short walk from where Congress has been attacking queer Americans this year, MAL takes place at the Hyatt Regency Washington for several days of intrigue, excitement, leather, and kink.

The Centaur Motorcycle Club — one of several similar groups dedicated to leather in the country — has been hosting MAL in its current form for more than 40 years. Originally a small gathering of like-minded people interested in the leather lifestyle, MAL has grown to include a full four days of events, taking place onsite at the Hyatt Regency Washington (400 New Jersey Ave., N.W.). Select partner happenings take place each night, and many more non-affiliated events are scattered across the DMV in honor of and inspired by MAL.

MAL Weekend has become an internationally renowned event that celebrates fetish culture, yet it also raises funds for LGBTQ organizations, “reinforcing its legacy as both a cultural and philanthropic cornerstone of the global leather community,” according to MAL organizers.

During the day, MAL events at the Hyatt include workshops, social gatherings, shopping, and other in-person engagements for the community.

“The Hyatt underwent an extensive top to bottom renovation after last year’s event,” says Jeffrey LeGrand-Douglass, the event chair. The lobby, meeting spaces, guest rooms, and other areas have been updated, he notes, “so I am very excited for our guests to experience the new design and layout for the first time. And of course as with every year, we look forward to the contest on Sunday afternoon and seeing who will become our new Mr. MAL.”

In the evening, MAL hands the reins to partner KINETIC Presents, the D.C.-based nightlife production company. KINETIC will host four consecutive nights of high-production events that fuse cutting-edge music, immersive environments, and performance. This year, KINETIC is popping open doors to new-to-MAL venues, international collabs, play zones, and a diverse lineup.

According to KINETIC managing partner Zach Renovátes, 2026 is the most extensive MAL production to date. “The talent lineup is unreal: an all-star roster of international DJs, plus drag superstar performances at the Saturday main event,” he says.

Renovátes added that he’s “most excited about the collaborations happening all weekend — from bringing in MACHO from WE Party Madrid, to teaming up with local leather groups, to nonprofit partners, and Masc Diva [a queer nightlife collective].”

Official MAL events begin on Thursday with the Full Package/Three Day Pass Pick-Up from 5:30-8:30 p.m. at the Hyatt.

Thursday night is also the KINETIC kickoff party, called LUST. Running 10 p.m. – 3 a.m., it’s being held at District Eagle. DJ Jay Garcia holds it down on the first floor, while DJ Mitch Ferrino spins in the expansive upstairs. LUST features special performances from the performers including Serg Shepard, Arrow, Chase, and Masterpiece.

Renovátes notes that the LUST opening party at District Eagle coincides with the bar’s grand re-opening weekend. The bar will unveil its new permanent home on the renovated second floor. “it felt like the perfect place to start Mid-Atlantic Leather weekend — right in D.C.’s only dedicated home for kink communities,” he says.

After Thursday night, Friday is when daytime events begin at the Hyatt. The Exhibit Hall, on the ballroom level below the lobby, hosts upwards of 30 vendors, exhibitors, and booths with leather goods, fetish wear, clothes, toys, other accessories, providing hours of time to shop and connect with attendees and business owners. The Exhibit Hall will be open on Friday from 4-10 p.m., as well as on Saturday and Sunday afternoons.

DC Health is once again back at MAL, to provide preventative health services. In the past, DC Health has provided MPox vaccines, Doxy PEP, HIV testing, Narcan kits, and fentanyl test strips. This booth will be open on Friday 4-10 p.m.

Later, at 6 p.m., the Centaur MC is holding its welcome reception on the ballroom floor. After the Centaur’s Welcome Reception, the MIR Rubber Social is 8-11 p.m. A Recovery Meeting is scheduled at 10 p.m.

Many attendees enjoy visiting the guest room levels of the hotel. Note that to get in an elevator up to a hotel room, a staff member will check for a hotel room wristband. Non-registered guests can only access host hotel rooms if they are escorted by a registered guest with a valid wristband. Registered guests are permitted to escort only one non-registered guest at a time. Non-registered guests with a wristband who are already in the hotel before 10 p.m. may remain until midnight. However, non-registered guests without a wristband will not be admitted after registration closes.

Friday night, for the first time, KINETIC Presents is joining forces with WE Party to bring MACHO to Washington, D.C. This official MAL Friday event delivers two stages and two genres. On the UNCUT XXL stage, international Brazilian circuit superstars Erik Vilar and Anne Louise bring their signature high-energy sound. On the MACHO stage, Madrid’s Charly is joined by Chicago’s tech-house force, Karsten Sollors, for a blend of techno and tech house. UNCUT also features the XL Play Zone, a massive, immersive space exclusive to this event. The party takes place at the Berhta space from 10 p.m.-4 a.m..

“This year we’re bringing back the two-room format we debuted at WorldPride for both Friday and Saturday, so attendees can really tailor their experience — whether they’re in the mood for circuit or tech house.” says Renovátes.

Directly after Friday’s UNCUT XXL, UNDERWORLD Afters takes over District Eagle, from 3:30-8 a.m. International DJ Eliad Cohen commands the music.

Saturday, the Exhibit Hall opens earlier, at 11 a.m.. DC Health will also be back from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Saturday is also time for one of the most anticipated events, the Puppy Mosh, running from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. During the event, pup culture comes to life, when pups, handlers, and friends can enjoy an inclusive, safe pup zone. There is also a Recovery Meeting at 11 a.m., and the IML Judges Announcement takes place at noon.

The popular Super Hero Meet Up will be held 1:30 p.m. – 3 p.m., sponsored by One Magical Weekend, for cosplayers, comic enthusiasts, and their friends.

From 2-6 p.m., the Onyx Fashion Show will take place to showcase and highlight people of color in leather.

Finally, the Leather Cocktail Party – the original event of MAL – will be held 7-9 p.m. in the Ballroom. While this requires special tickets to attend, at 9 p.m. is the MAL cocktail party, which is open to wider attendees.

The last event of Saturday leaves the hotel, again a partnership with KINETIC. Kicking off at 10 p.m. and running until 4 a.m., it’s just the second time that KINETIC’s Saturday night party is an official MAL event and serves as the main weekend engagement.

Saturday night’s centerpiece is called KINK: Double Trouble. The night will feature a first-ever back-to-back set from international electronic music icons Nina Flowers and Alex Acosta on the Circuit/Tribal Stage. The other room – the Tech House Stage – curated by The Carry Nation and Rose, provides a darker, underground counterpoint, reinforcing the event’s musical depth and edge.

Beyond the DJs, KINETIC has called in the big shots for this party: “RuPaul’s Drag Race” legends Nymphia Wind and Plastique Tiara are set to headline. The party also takes place at Berhta.

Sunday, back at the hotel, there will be another Recovery Meeting at 10 a.m., and the Exhibit Hall opens again from 11 a.m.-5 p.m.

At 1 p.m., the anticipated and prestigious Mr. MAL Contest that celebrates the achievements of the leather community will be held in the Ballroom. This highly sought after title gives one man the power to become the Mid-Atlantic Leather man of the year. Sash and title winners must be (1) male, (2), a resident of North America, (3) At least 21 years of age; and (4) self-identify as gay. The first Mr. MAL was crowned in 1985. The Winner of Mr. MAL has the privilege of later competing in International Mr. Leather (IML) in Chicago on Memorial Day Weekend 2025.

From 4 p.m. to 12 a.m., MAL will hold its Game Night for the gaymers in attendance. There will also be a special screening of A24’s new film, “Pillion,” about a man who is swept off his feet when an enigmatic, impossibly handsome biker takes him on as his submissive.

Sunday closes with a community partner event produced by Masc Diva, featuring Horse Meat Disco with support from Coach Chris, at A.I. Warehouse in the Union Market district. It’s the same team that produced HMD during WorldPride at A.I. Warehouse.

Note that there are several types of passes for attendance to the hotel and parties. KINK VIP Weekend Passes include express entry, VIP areas, and enhanced amenities throughout the weekend, while MAL Full Weekend Package holders receive access to the official Sunday closing event.

At last year’s MAL events, KINETIC Presents raised more $150,000 for LGBTQ charities, and expects to match or exceed that impact in 2026.

Renovátes stated that “now more than ever, it’s important to create safe, affirming spaces for our community — but it’s just as important to be visible and unapologetic. We want to make it clear that the LGBTQ+ and leather communities aren’t going anywhere. We’ve fought too long and too hard to ever feel like we have to shrink ourselves again, no matter what the political climate looks like.”

In addition to the KINETIC events, various LGBTQ bars will hold parties celebrating the theme of the weekend. For example, Kiki, located on U Street NW, is hosting a party called KINKI, hosted by DJ Dez, on Saturday night. Sister bar Shakiki, on 9th Street NW, is hosting a party called Railed Out, a fetish-inspired party that features a play zone, on Thursday night. Flash, on U Street NW, will hold its infamous Flashy Sunday party to close out the weekend.

Books

‘The Vampire Chronicles’ inspire LGBTQ people around the world

AMC’s ‘Interview with the Vampire’ has brought feelings back to live

Four kids pedaled furiously, their bicycles wobbling over cracked pavement and uneven curbs. Laughter and shouted arguments about which mystical creature could beat which echoed down the quiet street. They carried backpacks stuffed with well-worn paperbacks — comic books and fantasy novels — each child lost in a private world of monsters, magic, and secret codes. The air hummed with the kind of adventure that exists only at the edge of imagination, shaped by an imaginary world created in another part of the planet.

This is not a description of “Stranger Things,” nor of an American suburb in the 1980s. This is a small Russian village in the early 2000s — a place without paved roads, where most houses had no running water or central heating — where I spent every summer of my childhood. Those kids were my friends, and the world we were obsessed with was “The Vampire Chronicles” by Anne Rice.

We didn’t yet know that one of us would soon come out as openly bi, or that another — me — would become an LGBTQ activist. We were reading our first queer story in Anne Rice’s books. My first queer story. It felt wrong. And it felt extremely right. I haven’t accepted that I’m queer yet, but the easiness queerness was discussed in books helped.

Now, with AMC’s “Interview with the Vampire,” starring Jacob Anderson as Louis de Pointe du Lac — a visibly human, openly queer, aching vampire — and Sam Reid as Lestat de Lioncourt, something old has stirred back to life. Louis remains haunted by what he is and what he has done. Lestat, meanwhile, is neither hero nor villain. He desires without apology, and survives without shame.

I remember my bi friend — who was struggling with a difficult family — identifying with Lestat. Long before she came out, I already saw her queerness reflected there. “The Vampire Chronicles” allowed both of us to come out, at least to each other, with surprising ease despite the queerphobic environment.

While watching — and rewatching — the series over this winter holiday, I kept thinking about what this story has meant, and still means, for queer youth and queer people worldwide. Once again, this is not just about “the West.” I read comments from queer Ukrainian teenagers living under bombardment, finding joy in the show. I saw Russian fans furious at the absurdly censored translation by Amediateca, which rendered “boyfriend” as “friend” or even “pal,” turning the central relationship between two queer vampires into near-comic nonsense. Mentions of Putin were also erased from the modern adaptation — part of a broader Russian effort to eliminate queer visibility and political critique altogether.

And yet, fans persist to know the real story. Even those outside the LGBTQ community search for uncensored translations or watch with subtitles. A new generation of Eastern European queers is finding itself through this series.

It made me reflect on the role of mass culture — especially American mass culture — globally. I use Ukraine and Russia as examples because I’m from Ukraine, spent much of my childhood and adolescence in Russia, and speak both languages. But the impact is clearly broader. The evolution of mass culture changes the world, and in the context of queer history, “Interview with the Vampire” is one of the brightest examples — precisely because of its international reach and because it was never marketed as “gay literature,” but as gothic horror for a general audience.

With AMC now producing a third season, “The Vampire Lestat,” I’ve seen renewed speculation about Lestat’s queerness and debates about how explicitly the show portrays same-sex relationships. In the books, vampires cannot have sex in a “traditional” way, but that never stopped Anne Rice from depicting deeply homoromantic relationships, charged with unmistakable homoerotic tension. This is, after all, a story about two men who “adopt” a child and form a de facto queer family. And this is just the first book — in later novels we see a lot of openly queer couples and relationships.

The first novel, “Interview with the Vampire” was published in 1976, so the absence of explicit gay sex scenes is unsurprising. Later, Anne Rice — who identified as queer — described herself as lacking a sense of gender, seeing herself as a gay man and viewing the world in a “bisexual way.” She openly confirmed that all her vampires are bisexual: a benefit of the Dark Gift, where gender becomes irrelevant.

This is why her work resonates so powerfully with queer readers worldwide, and why so many recognize themselves in her vampires. For many young people I know from Eastern Europe, “Interview with the Vampire” was the first book in which they ever encountered a same-sex relationship.

But the true power of this universe lies in the fact that it was not created only for queer audiences. I know conservative Muslims with deeply traditional views who loved “The Vampire Chronicles” as teenagers. I know straight Western couples who did too. Even people who initially found same-sex relationships unsettling often became more tolerant after reading the books, watching the movie or the show. It is harder to hate someone who reminds you of a beloved character.

That is the strength of the story: it was never framed as explicitly queer or purely romantic, gothic and geeky audiences love it. “The Vampire Chronicles” are not a cure for queerphobia, but they are a powerful tool for making queerness more accessible. Popular culture offers a window into queer lives — and the broader that window, the more powerful it becomes.

Other examples include Will from “Stranger Things,” Ellie and Dina from “The Last of Us” (both the game and the series), or even the less mainstream but influential sci-fi show “Severance.” These stories allow audiences around the world to see queer people beyond stereotypes. That is the power of representation — not just for queer people themselves, but for society as a whole. It makes queer people look like real people, even when they are controversial blood-drinkers with fangs, or two girls surviving a fungal apocalypse.

Mass culture is a universal language, spoken worldwide. And that is precisely why censorship so often tries — and fails — to silence it.