Arts & Entertainment

Menzel’s magic

Broadway powerhouse brings summer tour to Wolf Trap next week

Singer Idina Menzel balances motherhood, touring, Broadway and Hollywood in a busy career but says she enjoys the concerts most. (Photo courtesy Concord Music Group)

‘An Evening with Idina Menzel’

Aug. 3, 8:15 p.m.

Wolf Trap Filene Center

1551 Trap Rd.

Vienna, VA

Tickets range from $20 (lawn) to $100 (orchestra pit)

Idinamenzel.com

Pretty much any veteran live performer will say they have some little personal “trick” they use to keep their most oft-performed material fresh. For Idina Menzel and her trademark “Wicked” showstopper “Defying Gravity,” it’s sometimes a gay teen — perhaps with a little projecting — that helps get her through the song.

Well, that and what she describes as kind of obligation she has to the star-making material.

“That song is a personal gift to me,” she says. “I have a personal debt I owe to that music. Because I have to sing it so much, people ask if it gets monotonous. I can truthfully say that doesn’t happen because every time I sing it, I come from a different place. It could be the young 14-year-old boy in the front row singing it along with me who may not have come out yet. I know how much the song means to him, so I can sing it to him that night. I think it’s a testament to how well written a song it is that it can speak to so many different people.”

Menzel brings her summer tour to Wolf Trap next week for her only D.C.-area appearance. The Tony winner, who’s become a household name since she debuted in “Rent” in 1996 and later in “Wicked” in 2003, also varies her set list slightly from city to city, another show-freshening trick she swears by. She’ll perform in Virginia with the National Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Steven Reineke.

“I’m excited about the show not only because of the material I’m doing, but because I feel like I’ve found a way to make every city have a show that’s unique to them,” Menzel, 41, says. “People should know when they come to see the show they can leave feeling like they got to know a little piece of who I am and it’s not the same everywhere. Every city’s just a little bit different.”

“I’ve been doing it with the symphony for almost three years already, which I truly love. It’s been a wonderful experience for me, which is why I continue to do it,” Menzel says. “There’s an intimacy I’m able to maintain even though I have all these musicians behind me. I had to strike a balance with it early on. It was a little bit of work for me to figure out how to do that, but now it’s pretty natural and organic.”

Even after appearing in two seasons of “Glee” and in films like “Rent” and Disney’s “Enchanted,” Menzel still finds singing live to be her favorite brand of performance.

“I definitely thrive off of the live audience and the adrenaline of being in the moment,” she says.

In 2009, Menzel had her first child, son Walker, with fellow Broadway actor and husband Taye Diggs. Before motherhood, Menzel had a strict regimen for keeping her vocals up, but now being more flexible with her schedule as a mother has only enhanced her performance experiences, she says.

“The more I sing the better for me. I’m like a marathon runner as far as running everyday. So that’s kind of how I approach it — athletically. And I’m just finding that being a mom and having a little boy now has changed my whole perspective on that. I used to have such a ritual and routine that I still try to keep, but if I deviate from it I’m a little less hard on myself, and in return I feel like the rewards are greater for me professionally. I may not be as prepared vocally, but then I’m on stage and I feel more free.”

Menzel’s summer tour includes old favorites from her roles on Broadway in “Wicked” and “Rent,” as well as other hits featured in her concert “Barefoot at the Symphony” that aired on PBS and has now been released on DVD.

“There are a few songs I wouldn’t leave stage without singing. I’m constantly changing [the set list], trying to tell different stories,” Menzel says. “It’s half and half music people would expect and the other stuff is new stuff I want to challenge myself with.”

Looking back, Menzel finds that she was in very different places in life during her appearances on “Glee” in the show’s first and third seasons. She was still adjusting to being a mom while filming the first season, but during the filming of the third season was more used to juggling parenthood and her career.

“The last season I was on I enjoyed it a lot more. I was learning how to balance motherhood and work for myself. I was enjoying the cast and I didn’t have to run home every second to pump my boobs or whatever,” Menzel says. “I hope [the cast] are all really appreciating it and enjoying it in the moment because you can easily lose sight of how incredible it is. I would love to do more TV, but my definitive wish was to get back to New York and do another show.”

In addition to touring, Menzel is working on a number of projects. She’s working alongside composers of original pieces for new musicals to act as a “muse,” singing and doing readings of their work so they can hear the results of their writing. She’s also thrilled to start work as Elsa in a new Disney movie called “Frozen” set for release in 2013.

“It’s amazing for me, like a dream,” she says. “It’s an animated Disney movie and there’s lots of music in it. It’s a beautiful story, and we just got started.”

And yes, as clichéd as it might sound for a Broadway powerhouse, Menzel is aware and appreciative of her gay following.

“I did the Atlantis cruise ship with 1,000 gay men and I had probably the greatest time I’ve ever had,” she says.

Though on one hand she says it makes no difference — “an audience is an audience, made up of all different kinds of people” — she says the gay kids who tell her “Wicked” helped them come out mean a lot.

“All that kind of stuff is part of the benefits I reap from what I do for a living. It enriches me as a person and I feel like everyone’s in it together out there.”

Gay conductor to lead NSO for Menzel show

By BRIAN T. CARNEY

Maestro Steven Reineke says his friend Idina Menzel wouldn’t want him to say too much about what she’ll be singing at their upcoming performance with the National Symphony Orchestra at Wolf Trap.

But he does mention, “She covers a lot of material in her set. And she tells great stories. She’s very interactive with the audience. There’s even some audience participation.”

He’s more forthcoming about the first half of the program, which will start with one of his own compositions. The gay composer and conductor wrote “Celebration Fanfare” when he was 25 (he turns 42 in September) and notes that the piece is still performed frequently by orchestras and concert bands across the country. The work is dedicated to Erich Kunzel, conductor of the Cincinnati Pops, who served as a mentor to Reineke and encouraged his career as both composer and conductor.

Reineke resisted the temptation to start the evening with his own version of “Defying Gravity,” though Reineke’s piece was written to celebrate another kind of flight — the centennial of the Wright Brother flight. He says it’s a funny coincidence that Broadway composer Stephen Schwartz used the same title for the Act I finale of “Wicked,” a number that has become a signature piece for Menzel.

“We just happened to come up with the same title. They have nothing to do with each other whatsoever,” he says.

Reineke started composing when he was a teenager. He remembers, “I had all this music running around my head. I started to plunk things out on the piano because I just needed to get these songs out. It wasn’t really a conscious choice.”

It was also about that time he realized he was gay.

”I came out to myself when I was 17 years old, a senior in high school getting ready to go off to college. I’ll never forget having that cathartic moment when I stared in the mirror and said the words out loud, ‘I am gay.’ That was the hardest part about the process.”

As he began his professional life, Reineke remained open about his sexuality and says it was “a no brainer” because “I was never really in. The more notoriety I got, the more it came up, and I’m just not the kind of person to deny it. I just treat it as a very normal part of life. There was no big coming out.”

Reineke isn’t sure why the “classical closet” (cultural critic K. Robert Schwarz’s term for the dearth of classical musicians who are openly LGBT) still persists so strongly. He does note, “I do wish that more people would treat is as a non-issue, whether they’re in the arts, or sports figures, or television or whatever.”

Staying in the closet, he says, only perpetuates myths.

“That’s one thing that keeps the stigma about it. People staying buried instead of saying, ‘Here I am, deal with it.’”

His sexuality has not played a major role in his musical career. As a composer, he often takes his cue from the visual and visceral imagery he finds in mythology and nature. Reineke, who initially wanted to be a film composer, says he needs a visual image in mind before he starts composing: “Basically I’m creating a soundtrack to my own movie in my own head.”

As a conductor and music director (he’s also music director of the New York Pops and the principal pops conductor for the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and the National Symphony Orchestra here in Washington), Reineke says his focus is on the audience and the musicians.

“I have no particular agenda other than the health and success of the orchestra and the good times had by an audience.”

Books

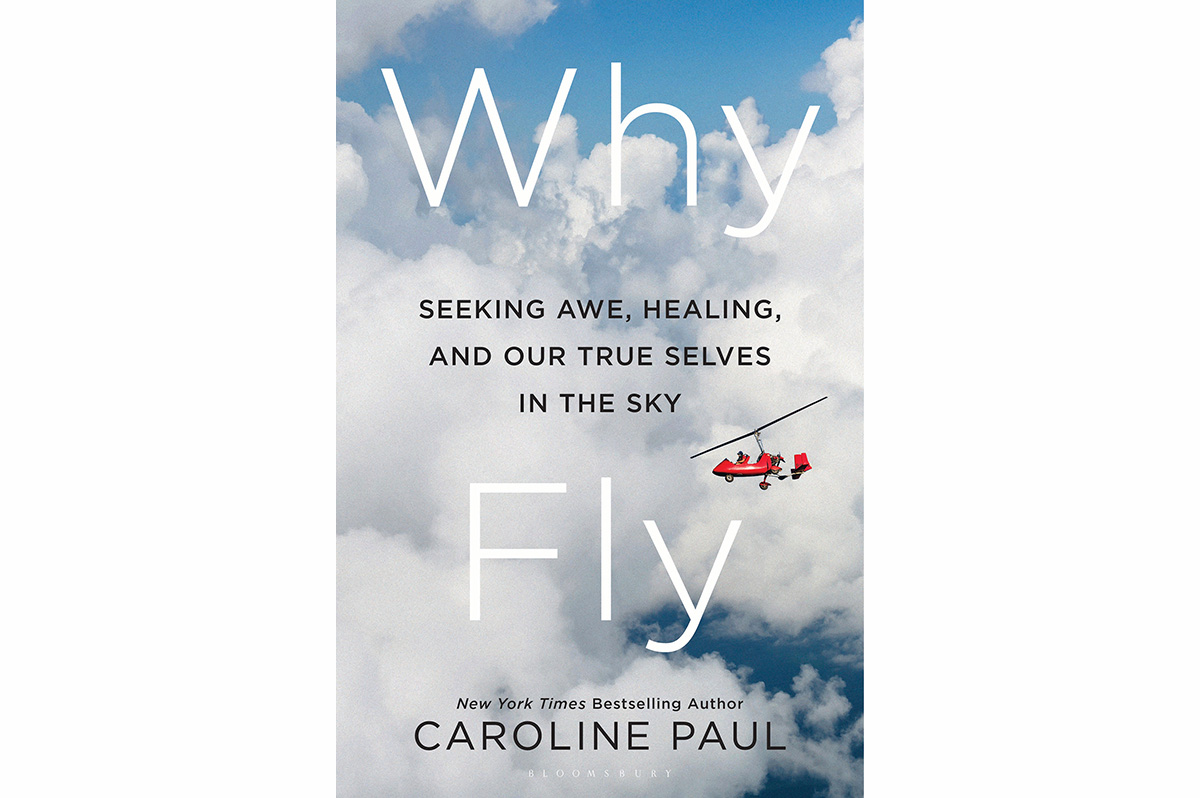

Love or fear flying you’ll devour ‘Why Fly’

New book chronicles a lifetime obsession with aircraft

‘Why Fly’

By Caroline Paul

c. 2026, Bloomsbury

$27.99/256 pages

Tray table folded up.

Check. Your seat is in the upright position, the airflow above your head is just the way you like it, and you’re ready to go. The flight crew is making final preparations. The lights are off and the plane is backing up. All you need now is “Why Fly” by Caroline Paul, and buckle up.

When she was very young, Paul was “obsessed” with tales of adventure, devouring accounts written by men of their derring-do. The only female adventure-seeker she knew about then was Amelia Earhart; later, she learned of other adventuresome women, including aviatrix Bessie Coleman, and Paul was transfixed.

Time passed; Paul grew up to create a life of adventure all her own.

Then, the year her marriage started to fracture, she switched her obsession from general exploits to flight.

Specifically, Paul loves experimental aircraft, some of which, like her “trike,” can be made from a kit at home. Others, like Woodstock, her beloved yellow gyrocopter, are major purchases that operate under different FAA rules. All flying has rules, she says, even if it seems like it should be as freewheeling as the birds it mimics.

She loves the pre-flight checklist, which is pure anticipation as well as a series of safety measures; if only a relationship had the same ritual. Paul loves her hangar, as a place of comfort and for flight in all senses of the word. She enjoys thinking about historic tales of flying, going back before the Wright Brothers, and including a man who went aloft on a lawn chair via helium-filled weather balloons.

The mere idea that she can fly any time is like a gift to Paul.

She knows a lot of people are terrified of flying, but it’s near totally safe: generally, there’s a one in almost 14 million chance of perishing in a commercial airline disaster – although, to Paul’s embarrassment and her dismay, it’s possible that both the smallest planes and the grandest loves might crash.

If you’re a fan of flying, you know what to do here. If you fear it, pry your fingernails off the armrests, take a deep breath, and head to the shelves. “Why Fly” might help you change your mind.

It’s not just that author Caroline Paul enjoys being airborne, and she tells you. It’s not that she’s honest in her explanations of being in love and being aloft. It’s the meditative aura you’ll get as you’re reading this book that makes it so appealing, despite the sometimes technical information that may flummox you between the Zen-ness. It’s not overwhelming; it mixes well with the history Paul includes, biographies, the science, heartbreak, and exciting tales of adventure and risk, but it’s there. Readers and romantics who love the outdoors, can’t resist a good mountain, and crave activity won’t mind it, though, not at all.

If you own a plane – or want to – you’ll want this book, too. It’s a great waiting-at-the-airport tale, or a tuck-in-your-suitcase-for-later read. Find “Why Fly” and you’ll see that it’s an upright kind of book.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Theater

Out actor Kevin Cahoon on starring role in ‘Chez Joey’

Arena production adapted from Broadway classic ‘Pal Joey’

‘Chez Joey’

Through March 15

Arena Stage

1101 Sixth St., S.W.

Tickets start at $93

Arenastage.org

As Melvin Snyder in the new musical “Chez Joey,” out actor Kevin Cahoon plays a showbiz society columnist who goes by the name Mrs. Knickerbocker. He functions as a sort of liaison between café society and Chicago’s Black jazz scene circa 1940s. It’s a fun part replete with varied insights, music, and dance.

“Chez Joey” is adapted from the Broadway classic “Pal Joey” by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart. It’s inspired by John O’Hara’s stories based on the exploits of a small-time nightclub singer published in The New Yorker.

A warm and humorous man, Cahoon loves his work. At just six, he began his career as a rodeo clown in Houston. He won the Star Search teen division at 13 singing songs like “Some People” from “Gypsy.” He studied theater at New York University and soon after graduating set to work playing sidekicks and comedic roles.

Over the years, Cahoon has played numerous queer parts in stage productions including “Hedwig and the Angry Inch,” “La Cage aux Folles,” “Rocky Horror” as well as Peanut in “Shucked,” and George the keyboardist in “The Wedding Singer,” “a sort of unicorn of its time,” says Cahoon.

Co-directed by Tony Goldwyn and the great Savion Glover, “Chez Joey” is a terrific and fun show filled with loads of talent. Its relevant new book is by Richard Lagravenese.

On a recent Monday off from work, Cahoon shared some thoughts on past and current happenings.

WASHINGTON BLADE: Is there a through line from Kevin, the six-year-old rodeo clown, to who we see now at Arena Stage?

KEVIN CAHOON: Anytime I want to land a joke in a theater piece it goes back to that rodeo clown. It doesn’t matter if it’s Arena’s intimate Kreeger Theatre or the big rodeo at the huge Houston Astrodome.

I was in the middle stadium and there was an announcer — a scene partner really. And we were doing a back and forth in hopes of getting laughs. At that young age I was trying to understand what it takes to get laughs. It’s all about timing. Every line.

BLADE: Originally, your part in “Chez Joey” Melvin was Melba who sings “Zip,” a clever woman reporter’s song. It was sort of a star feature, where they could just pop in a star in the run of “Pal Joey.”

CAHOON: That’s right. And in former versions it was played by Martha Plimpton and before her Elaine Stritch. For “Chez Joey,” we switched gender and storyline.

We attempted to do “Zip” up until two days before we had an audience at Arena. Unexpectedly they cut “Zip” and replaced it with a fun number called “I Like to Recognize the Tune,” a song more connected to the story.

BLADE: Wow. You must be a quick study.

CAHOON: Well, we’re working with a great band.

BLADE: You’ve played a lot of queer parts. Any thoughts on queer representation?

CAHOON: Oh yes, definitely. And I’ve been very lucky that I’ve had the chance to portray these characters and introduce them to the rest of the world. I feel honored.

After originating Edna, the hyena on Broadway in “The Lion King,” I left that to do “Hedwig and the Angry Inch” as standby for John Cameron Mitchell, doing one show a week for him.

Everyone thought I was crazy to leave the biggest musical of our time with a personal contract and getting paid more money that I’d ever made to get $400 a week at the downtown Jane Street Theatre in a dicey neighborhood.

At the time, I really felt like I was with cool kids. I guess I was. And I never regretted it.

BLADE: When you play new parts, do you create new backstories for the role?

CAHOON: Every single time! For Melvin, I suggested a line about chorus boys on Lakeshore Drive.

BLADE: What’s up next for Kevin Cahoon?

CAHOON: I’m about to do the New York Theatre Workshop Gala; I’ve been doing it for nine years in a row. It’s a huge job. I’ll also be producing the “Cats: The Jellicle Ball” opening on Broadway this spring; it’s a queer-centric uptown vogue ball with gay actor André de Shields reprising his role as “Old Deuteronomy.”

BLADE: There’s a huge amount of talent onstage in “Chez Joey.”

CAHOON: There is. I’m sharing a dressing room with Myles Frost who plays Joey. He won accolades for playing Michael Jackson on Broadway. We’ve become great friends. He’s a miracle to watch on stage. And Awa [Sal Secka], a D.C. local, is great. Every night the audience falls head over heels for her. When this show goes to New York, Awa will, no doubt, be a giant star.

BLADE: Do you think “Chez Joey” might be Broadway bound?

CAHOON: I have a good feeling it is. I’ve done shows out of town that have high hopes and pedigree, but don’t necessarily make it. “Chez Joey” is a small production, it’s funny, and audiences seem to love it.

The Capital Pride Alliance held the annual Pride Reveal event at The Schuyler at The Hamilton Hotel on Thursday, Feb. 26. The theme for this year’s Capital Pride was announced as: “Exist. Resist. Have the audacity!”

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

-

Federal Government4 days ago

Federal Government4 days agoTwo very different views of the State of the Union

-

Virginia5 days ago

Virginia5 days agoVa. activists preparing campaign in support of repealing marriage amendment

-

Opinions4 days ago

Opinions4 days agoThe global cost of Trump’s foreign aid ideology

-

Movies3 days ago

Movies3 days agoMoving doc ‘Come See Me’ is more than Oscar worthy