Opinions

Renewed hope in India

I now have more explicit legal protections there than here

India’s Supreme Court on Sept. 6, 2018, struck down the country’s colonial-era sodomy law. (Photo by Legaleagle86; courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

When I came out to my dad, one of the first things he said was: “I wonder how many people in our family were gay but couldn’t say anything.”

I once looked through the family tree he has kept for 25 years, scanning seven generations of direct ancestors and distant relatives, wondering whose truth died with them.

During one visit to India, my grandmother took me to visit an old friend of hers. He was smartly dressed and well spoken, the sole occupant of an apartment littered with books and art. As my grandmother explained, he was a “confirmed bachelor” who had never married.

I think of him often. I’ll never know for sure if he was gay or not, but I do know there were generations of gay men in India who only had two options: a marriage based on a lie or a quiet life alone in the closet. And I wonder how different my life would have been if my family had stayed in India instead of immigrating to America when I was three years old. Which option would I have picked?

Thankfully, I had other options. I grew up and came out in an America just beginning to awaken to the cause of LGBTQ equality. I followed Ellen DeGeneres out of the closet and Edie Windsor to the altar. Later, I followed my dreams all the way to Barack Obama’s White House.

For these reasons, among others, I will always be extraordinarily proud to be an American. In no other country is my story – immigrating, coming out, marrying the person I love and starting a family, serving the highest office in the land – even possible.

And yet, that pride has always come with a corresponding set of complicated emotions about India, a deep personal connection tempered by sadness, guilt, and resignation.

Recently, my husband and I have talked about living abroad for a year or two when our daughter is older. In many ways, living in India would be a powerful way to teach her about a country that may not be a part of her genetic makeup but is nonetheless a very real part of who she is, who her appa is, and the values we hope to instill in her.

But every time we talk about it, I rule it out. How could we live as a family – even temporarily, and even with the privilege of American citizenship – in a place where our very relationship is criminal?

All of that changed on Sept. 6, when India’s Supreme Court unanimously struck down Section 377, the provision of the penal code criminalizing homosexuality, and further ruled that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is prohibited.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of this ruling. Not only did Section 377 codify discrimination, it was used for years as a tool by government and police to raid, arrest, and stigmatize queer Indians. In their judgements, the Justices spoke to this long history of oppression, calling Section 377 “irrational, indefensible, and manifestly arbitrary,” speaking to the inherent dignity and equality owed LGBTQ individuals, and calling for full and equal protection under the law – a goal we have yet to attain here in America.

It’s not lost on me that, as a consequence of this historic ruling, I now have more explicit legal protection in the land of my birth than in the land that I love.

That said, this is just the first step. Much like Lawrence paved the way for the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and the freedom to marry, India too will have to grapple with the meaning and implementation of full equality for its LGBTQ citizens.

But for now, it signals the beginning of an end to loveless marriages and closeted confirmed bachelors. Even more importantly, it shows the way to a future of endless possibilities and unlimited options for future generations of Indians – and Indian Americans.

In January, my husband, daughter, and I will travel to India for a family reunion. In many ways, we will be returning to exactly the same country we’ve visited before. But in one very important way, we will be visiting a new land, with renewed hope for the future.

Gautam Raghavan served as President Obama’s liaison to the LGBTQ and AAPI communities from 2011 to 2014, currently advises the Indian American Impact Project and Biden Foundation, and is the editor of the forthcoming ‘West Wingers: Stories from the Dream Chasers, Change Makers, and Hope Creators Inside the Obama White House’ to be published by Penguin Books on Sept. 25.

Renee Good. Alex Pretti.

During this last year, I wondered who would be the first U.S. citizen to be shot by our government. It was not a matter of if, but when. Always.

And now we know.

I thought it would be soldiers. But the masked men got there first. Because when you mix guns and protests, guns inevitably go off. The powers that be always knew it, hoped for it, and wanted it to happen.

Why? Because masked men and guns instill fear. And that’s the point. Ask yourself when’s the last time you saw masked men and guns in our cities, or anywhere for that matter. I always thought that men masked men with guns robbed banks. I was wrong.

Masked men want to rob us of our dignity as human beings. Of our assurance in the calmness and contentment of our communities. They want to rob us of our trust in our institutions, and our faith in each other. And truly they want to rob us of the happiness and joy that we all constantly yearn to find in our lives.

But our only collective ability as a nation to push back is our protests. Peaceful protests. As Renee and Alex did.

But peaceful protests? Because they are the perfect power to shame the cowardice of those that believe guns and force are the only true authority. Fortunately, our last hope and fiercest ally is our Constitution, which gives us the power — and the right — to protest.

How much more peaceful can you get when you hear Renee Good’s last words, “I’m not mad at you, Dude.” I may be mad at the system, the government, the powers of unknown people pulling the strings but not you personally. “Dude.” Peaceful to the last word.

Yet, what becomes lost in the frantic pace of hair-trigger news cycles, of officials declaring impetuous damnations alongside johnny-on-the spot podcasters spouting their split-second opinions are the two human beings who have lost their lives.

How habituated we’ve become as we instantly devour their instant obituaries. The sum of their lives declared in less than 10 seconds of cellphone video. They haven’t just lost their lives. They’ve lost all of their lives. And now we watch over and over again as their death is re-revealed, re-churned, re-evaluated, and re-consumed. In that endless repetition, we forget the meaning of life itself.

We must remember that Renee and Alex believed in their communities, in the purpose of their work, in the happiness of their loves and lives, and in the dignity and curiosity of life itself. They were singular individuals who did not deserve to die at the end of a gun barrel for any reason, ever.

How fitting that Renee was a poet. Sometimes in confronting the massiveness of loss in our lives, we look to our poetry and our psalms, our hymns and our lullabies, to find a moment of solace in our communal grief, and to remember Renee and Alex, for what they gave us in life.

Yet, at this moment, I cannot escape the reality of what was taken from them so soon, so violently and so forever. They were exceptionally courageous and normal people, and for that reason, I must remember them through a poem to explain to me, and others, the unexplainable.

I dream of this not happening.

I dream this day and night.

For none of this is real.

And none of this is right.

I dream of these sons and daughters

who now will not go home,

and dream of their mothers and fathers,

who now must stand alone.

I dream of all the flowers that they will never hold —

the kisses never shared again, the secrets to not be told.

I dream of all the sunsets that for them will never set,

I dream of all the love they gave and now they must forget.

I dream of all their dinners

with wine to never spill,

or books to read, or bread to break

or babies to be held.

I dream of each one still reaching

in the middle of the night,

for a hand that needs another

to stop a nightmare’s flight.

I dream of them not dreaming,

which I could never do,

for how can you not dream a dream

that never will come true.

I dream of this not happening.

I dream this day and night.

For none of this is real

And none of this is right.

Carew Papritz is the award-winning author of “The Legacy Letters,” who inspires kids to read through his “I Love to Read” and the “First-Ever Book Signing” YouTube series.

Opinions

Gay Treasury Secretary’s silence on LGBTQ issues shows he is scum

Scott Bessent is a betrayal to the community

We all know the felon in the White House is basically a POS. He is an evil, deranged, excuse for a man, out only for himself. But what is just as sad for me is the members of the LGBTQ community serving in his administration who are willing to stand by silently, while he screws the community in so many ways. The leader, with his silence on these issues, is the highest ranking “out” gay ever appointed to the Cabinet; the current secretary of the treasury, the scum who goes by the name, Scott Bessent.

Bessent has an interesting background based on his Wikipedia page. He is from South Carolina and is what I would call obscenely wealthy. According to his financial assets disclosure to the U.S. Office of Government Ethics, Bessent’s net worth was at least $521 million as of Dec. 28, 2024; his actual net worth is speculated to be around $600 million. He married John Freeman, a former New York City prosecutor, in 2011. They have two children, born through surrogacy. I often wonder why guys like Bessent conveniently forget how much they owe to the activists in the LGBTQ community who fought for the right for them to marry and have those children. Two additional interesting points in the Wikipedia post are Bessent reportedly has a close friendship with Donald Trump’s brother Robert, whose ex-wife, Blaine Trump, is the godmother of his daughter. The other is disgraced member of the U.S. House of Representatives, John Jenrette, is his uncle.

Bessent has stood silent during all the administrations attacks on the LGBTQ community. What does he fear? This administration has kicked members of the trans community out of the military. Those who bravely risked their lives for our country. The administration’s policies attacking them has literally put their lives in danger. This administration supports removing books about the LGBTQ community from libraries, and at one point even removed information from the Pentagon website on the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the first atomic bomb, thinking it might refer to a gay person. It was actually named after Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot, Col. Paul Tibbets. That is how dumb they are. Bessent stood silent during WorldPride while countries around the world told their LGBTQ citizens to avoid coming to the United States, as it wouldn’t be safe for them, because of the felon’s policies.

Now the administration has desecrated the one national monument saluting the LGBTQ community, Stonewall, in New York City, by ordering the removal of the rainbow flag. The monument honors the people who get credit for beginning the fight for equality that now allows Bessent, and his husband and children, to live their lives to the fullest. That was before this administration he serves came into office. I hope his children will grow up understanding how disgusting their father’s lack of action was. That they learn the history of the LGBTQ community and understand the guts it took for a college student Zach Wahls, now running for the U.S. Senate from Iowa, to speak out for his “two moms” in the Iowa State Legislature in 2011, defending their right to marry.

Bessent is sadly representative of the slew of gays in the administration, all remaining silent on the attacks on the community. They are mostly members of the Log Cabin Republicans who have given up on their principles, if they ever had any, to be subservient to the felon, and the fascists around him, all for a job.

There are so many like them who supported the felon in the last election. Some who believed in Project 2025, others who didn’t bother to read it. Many continue to stand with him, with the sycophants in the Congress, and the incompetents and fascists in the administration, as they work to destroy our country and end the democracy that has served us so well for 250 years. To keep out all immigrants from a nation of immigrants. They all seem to forget it was immigrants who built our country, who fought against a king, and won. These sycophants now support the man who wants to be king. Who openly says, “I am president I can do anything only based on my own morality,” which history clearly shows us he has none.

I believe we will survive these horrendous times in American history. We have fought a king before and won. We have kept our country alive and thriving through a civil war. We the people will defeat the felon and his minions, along with the likes of those who stood by silently like Scott Bessent. They seem to forget “Silence = Death.”

Peter Rosenstein is a longtime LGBTQ rights and Democratic Party activist.

Opinions

Unconventional love: Or, fuck it, let’s choose each other again

On Valentine’s Day, the kind of connection worth celebrating

There’s a moment at the end of “Love Jones” — the greatest Black love movie of the 21st century — when Darius stands in the rain, stripped of bravado, stripped of pride, stripped of all the cleverness that once protected him.

“I want us to be together again,” he says. “For as long as we can be.”

Not forever. Not happily ever after. Just again. And for as long as we can. That line alone dismantles the fairy tale.

“Love Jones” earns its place in the canon not because it is flawless, but because it is honest. It gave us Black love without sanitizing it. Black intellect without pretension. Black romance without guarantees. It told the truth: that love between two whole people is often clumsy, ego-driven, tender, frustrating, intoxicating—and still worth choosing.

That same emotional truth lives at the end of “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” my favorite movie of all time. Joel and Clementine, having erased each other, accidentally fall back into love. When they finally listen to the tapes that reveal exactly how badly they hurt one another, Clementine does something radical: she tells the truth.

“I’m not perfect,” she says. “I’ll get bored. I’ll feel trapped. That’s what happens with me.”

She doesn’t ask Joel to deny reality. She invites him into it. Joel’s response isn’t poetic. It isn’t eloquent. It’s not even particularly brave. He shrugs.

“Ok.”

That “OK” is one of the most honest declarations of love ever written. Because it says: I hear you. I see the ending. I know the risk. And I’m choosing you anyway.

Both films are saying the same thing in different languages. Nina and Darius. Clementine and Joel. Artists and thinkers. Romantics who hurt each other not because they don’t care — but because they do. Deeply. Imperfectly. Humanly.

They argue. They retreat. They miscommunicate. They choose pride over vulnerability and distance over repair. Love doesn’t fail because they’re careless — it fails because love is not clean.

What makes “Love Jones” the greatest Black love movie of the 21st century is that it refuses to lie about this. It doesn’t sell permanence. It sells presence. It doesn’t promise destiny. It offers choice.

And at the end — just like “Eternal Sunshine” — the choice is made again, this time with eyes wide open.

When Nina asks, “How do we do this?” Darius doesn’t pretend to know.

“I don’t know.”

That’s the point.

Love isn’t a blueprint. It’s an agreement to walk forward without one.

I recently asked my partner if he believed in soul mates. He said no—without hesitation. When he asked me, I told him I believe you can have more than one soul mate, romantic or platonic. That a soul mate isn’t someone who saves you — it’s someone whose soul recognizes yours at a particular moment in time.

He paused. Then said, “OK. With those caveats, I believe.”

That felt like a Joel shrug. A grown one.

We’ve been sold a version of love that collapses under scrutiny. Fairy tales promised permanence without effort. Celebrity marriages promised aspiration without truth. And then reality — messy, public, human—stepped in. Will and Jada didn’t kill love for me. They clarified it.

No relationship is perfect. No love is untouched by disappointment. No bond survives without negotiation, humility, and repair. What matters isn’t whether love lasts forever. What matters is whether, when confronted with truth, you still say yes.

“Love Jones” ends in the rain. “Eternal Sunshine” ends in a hallway. No swelling orchestras. No guarantees. Just two people standing at the edge of uncertainty saying: Fuck it. I love you. Let’s do it again.

That’s not naïve love. That’s courageous love.

And on Valentine’s Day — of all days — that’s the kind worth celebrating.

Randal C. Smith is a Chicago-based attorney and writer focusing on labor and employment law, civil rights, and administrative governance.

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoTrump falsely links trans people to terrorism

-

Virginia5 days ago

Virginia5 days agoFellow lawmakers praise Adam Ebbin after Va. Senate farewell address

-

National5 days ago

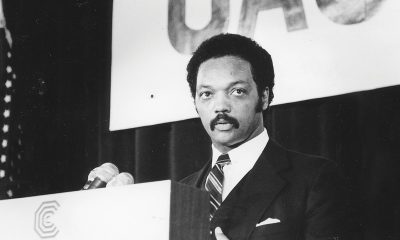

National5 days agoLGBTQ activists mourn the Rev. Jesse Jackson

-

Massachusetts4 days ago

Massachusetts4 days agoEXCLUSIVE: Markey says transgender rights fight is ‘next frontier’