Opinions

Census 2020 is complicated, but it counts

Critical funds for LGBTQ Americans at risk

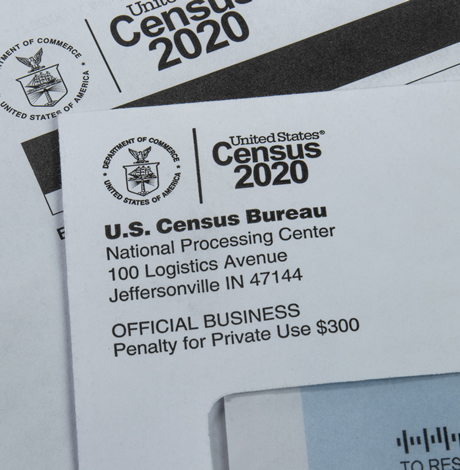

By now, everyone should have received a mailing from the U.S. Census Bureau to get counted. I have complicated feelings about the census.

While the census is critically important to ensure a fair allocation of funding for services and political representation, it will not deliver the full acceptance and freedom of the LGBTQ community. After all, it’s a government survey. It will not capture the breadth of human experience in America today. So why are my feelings complicated?

Some aspects of my identity are reflected in the census. I’m gay. There is no census question asking about sexual orientation. Yet, the relationship question counts same-sex married spouses and unmarried partners. While being a same-sex couple is a poor proxy for sexual orientation, the 2010 census uncovered more than 700,000 same-sex couples in the U.S.

I’m a dad of an adopted African-American child. Many LGBTQ people build families through adoption. The census counts transracial families. In fact, every year census data is used to allocate $8 billion for foster care and adoption assistance that can help queers start families.

At the same time, my community is erased. Trans and gender non-conforming people must respond to a binary sex question. They must choose between their sex assigned at birth or how they identity today. The census asks about biology, not identity, and today while Facebook has more than 52 genders, the U.S. government only has two. It sucks.

Even India, Nepal, Pakistan (and Washington and Oregon) recognize a third gender. I and my organization, the National Queer Asian Pacific Islander Alliance have urged the Census Bureau to recognize all of our community.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, health care is especially critical. The census is used to allocate $311 billion in medical assistance annually, according to the George Washington University Institute for Public Policy. More resources flow to where there is greater need based on the relative size of the population.

I teach a class on Asian American Queerness at Hunter College CUNY. So many of my students benefit from the $29 billion in financial aid (Pell Grants) for college every year.

The census continues to be used to allocate $645 million in HIV funding. I could go on and recount the importance of an accurate census:

• $457 million for community mental health services;

• $133 million for domestic violence prevention programs;

• $48 million for community arts programs and for queer and trans artists;

• $4.7 million to prevent abuse, neglect, and exploitation of elders.

The more people who respond to the census, the more likely resources will flow to under-resourced communities.

But for me the most importance aspect of the census is the political influence that the data drives. The census can be a check on the outsized political influence that some intolerant states command when apportioning congressional seats among the states based on population.

Census data is also used to redraw congressional, state legislative and city council district boundaries to make them equal in population. Sure, some districts can be gerrymandered. But voting rights advocates can also use the data to draw districts that give communities of color, and those who have be traditionally underrepresented, a voice in the halls of power.

The census is required by law. People can be fined $100 for not responding. Federal law also ensures that personal information is private and may not be shared with the immigration service, IRS, or law enforcement.

NQAPIA is monitoring the census to keep our community safe. We have lawyers ready to sue if there are breaches and who are available to answer questions. You can report problem to us at bit.ly/2ULyiLy.

The census holds a lasting impact. To be missed is to be gone for the next 10 years. Let’s be counted.

Glenn D. Magpantay is a long-time civil rights lawyer who led community education and advocacy efforts for Census 2000 and 2010. He is executive director of the National Queer Asian Pacific Islander Alliance.

Opinions

Supreme Court decision on opt outs for LGBTQ books in classrooms will likely accelerate censorship

Mahmoud v. Taylor ruling sets dangerous precedent

With its ruling Friday requiring public schools to allow parents to opt their children out of lessons with content they object to — in this case, picture books featuring LGBTQ+ characters or themes — the Supreme Court has opened up a new frontier for accelerating book-banning and censorship.

The legal case, Mahmoud v. Taylor, was brought by a group of elementary school parents in Montgomery County, Md., who objected to nine books with LGBTQ+ characters and themes. The books included stories about a girl whose uncle marries his partner, a child bullied because of his pink shoes, and a puppy that gets lost at a Pride parade. The parents, citing religious objections, sued the school district, arguing that they must be given the right to opt their children out of classroom lessons including such books. Though the district had originally offered this option, it reversed course when the policy proved unworkable.

In its opinion the court overruled the decisions of the lower courts and sided with the parents, ruling that books depicting a same-sex wedding as a happy occasion or treating a gay or transgender child as any other child were “designed to present … certain contrary values and beliefs as things to be rejected.” The court held that exposing children to lessons including these books was coercive, and undermined the parents’ religious beliefs in violation of the free exercise clause of the First Amendment.

This decision is the latest case in recent years to use religious freedom arguments to justify decisions that infringe on other fundamental rights. The court has used the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to permit companies to deny their employees insurance coverage for birth control, allow state-contracted Catholic adoption agencies to refuse to work with same-sex couples, and permit other businesses to discriminate against customers on the basis of their sexual orientation.

Here, the court used the Free Exercise Clause to erode bedrock principles of the Free Speech Clause at a moment when free expression is in peril. Since 2021, PEN America has documented 16,000 instances of book bans nationwide. In addition, its tracking shows 62 state laws restricting teaching and learning on subjects from race and racism to LGBTQ+ rights and gender — censorship not seen since the Red Scare of the 1950s.

Forcing school districts to provide “opt outs” will likely accelerate book challenges and provide book banners with another tool to chill speech. School districts looking to avoid logistical burdens and controversy will simply remove these books, enacting de facto book bans that deny children the right to read. The court’s ruling, carefully couched in the language of religious freedom, did not even consider countervailing and fundamental free speech rights. And it will make even more vulnerable one of the main targets of those who have campaigned for book bans: LGBTQ+ stories.

When understood in this wider context, it is clear that this case is about more than religious liberty — it is also about ideological orthodoxy. Many of the opt-out requests in Montgomery County were not religious in nature. When the reversal of the opt-out policy was first announced, many parents voiced concerns that any references to sexual orientation and gender identity were age-inappropriate.

The decision could allow parents to suppress all kinds of ideas they might find objectionable. In her dissent, Justice Sotomayor cites examples of objections parents could have to books depicting patriotism, interfaith marriage, immodest dress, or women’s rights generally, including the achievements of women working outside the home. If parents can demand a right to opt their children out of any topic to which they hold religious objections, what is to stop them from challenging books featuring gender equality, single mothers, or even a cheeseburger, which someone could theoretically oppose for not being kosher? This case throws the door open to such possibilities.

But the decision will have an immediate and negative impact on the millions of LGBTQ+ students and teachers, and students being raised in families with same-sex parents. This decision stigmatizes LGBTQ+ stories, children, and families, undermines free expression and the right to read, and impairs the mission of our schools to prepare children to live in a diverse and pluralistic society.

Literature is a powerful tool for building empathy and understanding for everyone, and for ensuring that the rising generation is adequately prepared to thrive in a pluralistic society. When children don’t see themselves in books they are left to feel ostracized. When other children see only people like them they lose out on the opportunity to understand the world we live in and the people around them.

Advocates should not give up but instead take a page from the authors who have written books they wished they could have read when they were young — by uplifting their stories. Despite this devastating decision, we cannot allow their voices to be silenced. Rather, we should commit to upholding the right to read diverse literature.

Elly Brinkley is a staff attorney with PEN America.

Opinions

Pragmatic presidents invest in America

We need targeted, accountable investment in workforce stability

America may soon elect a president who identifies as LGBTQ. This possibility is no longer far-fetched, nor should it be alarming. What matters far more than who the president is, is whom the president serves.

In America, we care who the president loves because we want to know whether they love the people they represent. Not just the powerful or the visible, but those struggling to contribute more fully. The farmer in Iowa. The single mother in Ohio. The veteran in Houston who sleeps in his truck.

The moral test of any president is whether they recognize that a nation cannot call itself strong when millions of its people are locked out of participating in the economy. This is not sentiment. It is strategy.

We are heading toward a century of global competition where population, productivity, and workforce strength will decide which nations lead. The United States cannot afford to ignore the foundational truth that economic health begins with human stability. Without a well-fed, well-housed, well-prepared workforce, the American economy simply cannot compete.

Today, millions of Americans remain outside the labor force. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, roughly six million working-age Americans are not working or actively looking for work. Another 36.5 million live below the poverty line. Many of them lack the basic conditions required to contribute to our modern economy: shelter, nutrition, healthcare, or safety.

The result is predictable. A smaller workforce. Greater dependencies. Stagnant productivity. In 2024, the Congressional Budget Office projected a long-term decline in labor force participation unless structural barriers are addressed. This is not only an economic issue. It is a national security issue.

China and India are investing heavily in their own labor capacity. Meanwhile, we risk squandering ours. This is the backdrop against which the next president, whoever they are, must lead.

The role of government is not to provide individual comfort or cradle-to-grave care; that responsibility rightly belongs to families, communities, and civil society. Its role is to maintain the conditions necessary for every willing individual to contribute productively and invest with confidence. This means access to a safe home. It means access to basic nutrition. It means access to the building blocks of a productive life. Securing for our work forces what the Apostle Paul called diatrophas and skepasmata; or food and a place to sleep. These are not luxuries or favors. They are investments that yield growth in national capacity.

Too often these issues are framed in moral or ideological terms rather than pragmatic business interests. This rhetoric can mask poor planning, inefficiencies, and broken promises that leave communities worse off. Meanwhile these concerns go beyond common sense. They make business sense.

Consider housing. The National Low Income Housing Coalition reports a shortage of more than seven million affordable rental homes for extremely low-income households. This gap affects workforce mobility, job retention, and family stability. In cities with severe housing stress, employers cannot fill jobs because workers cannot live nearby.

Or take hunger. The USDA estimates that more than 47 million Americans live in food-insecure households. Children who are malnourished underperform in school. Adults who skip meals cannot stay focused on work. These are not abstract concerns. They are immediate threats to productivity and growth.

A president who understands this will not be swayed by ideology. They will ask: What strengthens our democracy? What builds a workforce that can out-innovate, out-produce, and out-lead our rivals?

The answer is not more bureaucracy. It is a targeted, accountable investment in workforce stability. Presidents should promote responsible public-private partnerships and remove barriers to full engagement. Communities need to strengthen local support and work with businesses on food, housing, and job training. Businesses recognize the returns on investments in workforce development and inclusive workplaces. Individuals should engage locally, build skills, and participate in practical solutions for community prosperity.

There is precedent. Conservative leaders have long understood that a stable society is a prerequisite for economic freedom. Abraham Lincoln supported land grants and public education. Dwight Eisenhower built the interstate system to connect markets and communities. Ronald Reagan expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit.

The next president should recognize these approaches. It is time to revive a governing vision that puts dignity at the heart of national strategy. That includes all Americans, from skilled professionals to warehouse workers, nurse’s aides, and long-haul truck drivers. Everyone has a responsibility to do their part to keep the economy moving.

This is where leadership matters. Not in posing as a cultural warrior, but in protecting our investments in the people who keep the nation running. A president who cares about this country will not ask what’s needed to make things easier. They will ask what’s needed to help us thrive together. They will help us choose the right way, the hard way, and maybe even the long way because building a competitive economy and a secure nation requires investing in the realities that make that happen.

If the next president can rise to that standard, then identity will matter far less than results. And maybe that is the clearest sign of progress yet.

Will Fries is a Maryland communications strategist with experience in multiple major presidential campaigns.

Opinions

We can’t afford Medicaid cuts in fight against HIV

A dangerous message about whose lives are deemed worth protecting

Right now, members of Congress are considering a budget proposal that would rip away life-saving health care coverage, particularly Medicaid from millions of people in the United States. This isn’t just unjust—it’s dangerous.

Since the late 1970s, there has been a strong push to advance the rights and well-being of LGBTQ+ elders, including the growing number of people aging with HIV. This community faces unique and often complex quality of life issues that require consistent, comprehensive care. Medicaid provides essential coverage for these services, including access to HIV medications, primary and specialist care, long-term care, and behavioral health support. Proposed cuts to Medicaid would destabilize this vital lifeline, threatening the health and dignity of one of the most medically vulnerable and historically marginalized communities in our country.

Congress is deciding just how deeply Medicaid could be cut. What’s at stake amounts to one of the most significant threats to public health in recent memory—one that would have a devastating impact on people aging with HIV.

The facts are clear: Medicaid is the single largest source of health care coverage for people living with HIV in the United States, covering roughly 4 in 10 people living with the disease. Many of those individuals are older people who rely on Medicaid not just for access to HIV treatments, but for managing other conditions that often accompany aging with HIV—such as cardiovascular disease, cognitive issues, and diabetes.

We have made remarkable progress in responding to HIV. Today, with effective treatment, people living with HIV can lead long, healthy lives. When HIV is suppressed to undetectable levels, it cannot be transmitted sexually. But this progress depends on consistent access to care. Without Medicaid, many people risk losing access to the medications that keep them healthy and alive—and that help prevent the transmission of HIV.

Moreover, Medicaid expansion has been directly associated with increased access to PrEP, a medication that is up to 99% effective at preventing HIV acquisition. Scaling back Medicaid would not only affect people already living and aging with HIV, but it would also limit preventive care that is essential to reducing new cases of HIV. In a world that too often dismisses older people as non-sexual and overlooks their need for HIV prevention services, the last thing we need is to further restrict access to sexual health services.

Older people with HIV often experience higher levels of isolation, stigma, and economic insecurity. They are more likely to be housing insecure and to have little to no family support. Medicaid helps older people maintain independence and age with dignity. Cutting Medicaid isn’t just a policy decision—it would create real hardship and suffering in the community.

Across the country, advocates and service providers see this reality every day. Countless LGBTQ+ elders and people aging with HIV rely on Medicaid for basic care and services. But that security can disappear quickly. That’s why taking action—right now—to help protect Medicaid is critical.

Here’s what you can do:

Call your members of Congress at 866-426-2631 and tell them “No cuts to Medicaid.”

Write your members of Congress and tell them that Medicaid must be protected for people aging with HIV. Our colleagues at AIDS United have created a simple and effective tool to help you reach your representatives directly.

Join the SAGE Action Squad. When you sign up, you’ll receive alerts and updates on urgent advocacy issues affecting LGBTQ+ elders and people aging with HIV. It’s a powerful way to stay informed and engaged—and to ensure your voice is part of this movement.

We understand that budget decisions are complex. But we also believe that protecting health care for the most vulnerable members in our community should never be negotiable. Cutting Medicaid doesn’t just reduce spending—it puts lives at risk. It creates new barriers for people aging with HIV to access care, manage their health, and live with dignity. It also limits critical prevention services for those vulnerable to acquiring HIV, undermining efforts to end the HIV epidemic.

If enough of us act, we can help stop these Medicaid cuts from happening. We can ensure that Medicaid continues to serve the people who need it most.

SAGE has been at the forefront of this fight for decades. We’ve helped secure victories in access, equity, and representation. But we can’t do it alone. We must come together to defend the programs that safeguard the health, dignity, and future of our community. Cutting Medicaid would not only roll back progress—it would deepen disparities, put lives at risk, and send a dangerous message about whose lives are deemed worth protecting. We must speak out and demand that our elected leaders prioritize care over cuts. Let’s protect Medicaid. Let’s protect people aging with, and vulnerable to, HIV. Let’s protect our community—and build a future where every older person with HIV can age with health, respect, and pride.

Terri L Wilder, MSW is the HIV/Aging Policy Advocate at SAGE where she implements the organization’s federal and state HIV/aging policy priorities.

-

U.S. Supreme Court3 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court3 days agoSupreme Court upholds ACA rule that makes PrEP, other preventative care free

-

U.S. Supreme Court3 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court3 days agoSupreme Court rules parents must have option to opt children out of LGBTQ-specific lessons

-

India5 days ago

India5 days agoIndian court rules a transgender woman is a woman

-

National4 days ago

National4 days agoEvan Wolfson on the 10-year legacy of marriage equality