National

Locked up in the Land of Liberty: Part II

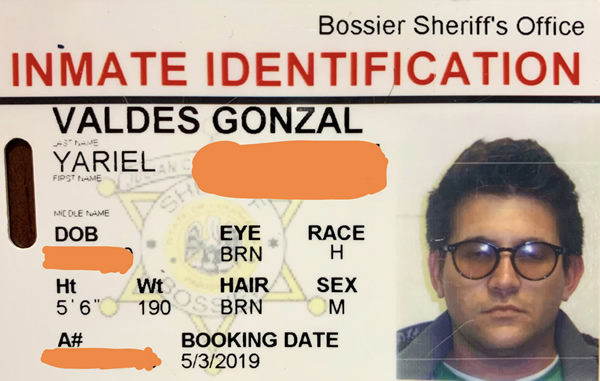

Yariel Valdés González suffered abuse at La. jail

Editor’s note: Washington Blade contributor Yariel Valdés González fled his native Cuba to escape persecution because of his work as an independent journalist. He asked for asylum in the U.S. on March 27, 2019. He spent nearly a year in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody until his release on March 4, 2020.

Valdés has written about his experiences in ICE custody that the Blade will publish in four parts. The Blade published the first part on July 7.

Welcome to hell! (May 3, 2019)

The trip between Mississippi and Louisiana took more than six hours, six endless hours shackled and handcuffed to go to an unknown location! We were in a mobile jail: The windows were secured with bars and inside there was a padlocked security gate, which separated us from the officers in charge of our transportation. I was traveling with Jéiser, a Honduran friend, on a metal seat that numbed my butt until I could barely feel it. The handcuffs were already beginning to leave marks on my hands.

The landscape was a great distraction: Immense forests, vast lakes, fields and houses submerged by the floods from the last rains, a few buildings, car dealerships. It was a quick glimpse of daily life in America, so close and yet so far away.

The truth was I did not want to miss out on that route, but sleepiness periodically defeated me. I had hardly slept at all the night before. I was lying on the floor in Tallahatchie waiting for the transfer, a long and tedious process.

Resting on the bus was in intervals because the handcuffs made it impossible to get into a comfortable position. We also had to go to the bathroom cuffed hand and foot and eat what they gave us: A bag with two pieces of bread, cheese, mayonnaise, some chips, some sweet cookies and a tiny bottle of water. You had to become almost a contortionist to eat like that, but necessity works wonders! And they even told us not to throw anything on the floor, an inconceivable order while being locked up in a moving vehicle.

We finally reached our destination: Bossier Parish Medium Security Facility. The jail from the outside looks like a large, rough, imposing and challenging concrete cube. A fat woman who spoke in Spanish and English entered the bus and led us into the prison. Several officers proceeded to free us from the handcuffs as soon as we got out. Finally! They gave me a cardboard box with my name that was, conveniently, already waiting for me! I also had a new identification number (also known as an A number), 91964, which would be my ID inside the jail.

We had to put our clothes and shoes in the box and they gave us the uniform: A bright yellow shirt and pants and plastic flip-flops so rough they looked like enemies of the feet. I think no one in this country would think of wearing them, much less the fabric of these clothes that are made in Pakistan with a 65 percent polyester and 35 percent cotton blend. The result is a garment that is rough to the touch and does not yield, further contributing to the feeling of confinement and suffocation. It is as if the uniform also reminds you that you are in prison.

After completing the registration process, they brought us to a classroom where we waited for the prison’s warden. He soon arrived with the help of the fat lady who translated into Spanish as he explained the rules of the game.

“You are not prisoners,” he warned in a stern voice. “You are only detained until your immigration process is complete, about which we have no power or information. We are only here to feed and care for you.”

The warden added that although we are not “prisoners,” as counterproductive it may seem, we are subject to the rules of any prisoner in this jail.

“Anyone who breaks them will be punished,” added that large man in his 40s with a threatening tone.

I was nevertheless happy to be out of Tallahatchie. I would only wait a few days here to see the judge and be able to go free to continue my process. I was told the judge can “reactivate” my parole and everything would be resolved soon. They led me to my dorm after the “friendly” welcome ended. A prisoner dressed in green stripes who was standing very close to the entrance gave me a bag with some belongings and a very thin mattress. They opened the door and I went inside.

People inside crowded around the door and a panel of glass that allowed us to see into the room. Everyone was eager to see the new victims.

“That is a Cuban,” one of them said as soon as I entered.

They immediately took my mattress when they heard my affirmative answer and helped me to settle in my bed, number 30 in the C-3 pod.

“Welcome to hell!,” another Cuban told me and little by little everyone was in charge of erasing all the hopes that sustained me.

“Nobody leaves here,” they said to me and the joy for the supposed end was fading.

They began to deny every bit of information that I brought with me. There are Cubans here who have been in prison for a year or more, only in this detention center. I could not believe it. All of them had “credible fear,” all of them were entitled to parole and all of them were locked up with their dreams hanging by a thread.

Many of the Cubans have already lost their asylum hearings and are appealing the immigration judge’s decision.

“The only ones who have left here have been deported or who have been out of Cuba for more than two years,” they warned me.

That option doesn’t apply to me, at least not at the moment, because I’ve only been off the island for seven months.

I felt like all the doors were closing. Each conversation was a slam to my longings, a slap that plunged me deeper into a sea of despair. I exploded. I burst into tears in my bed, under the blanket. I couldn’t control myself. I spent a long time trying to overcome that painful and bitter trance on my own, drawing upon my strength to get up from my hiding place.

I barely made it. I went to make the free calls that prisons always offer every time you arrive at a new detention center when you still don’t have money on your phone account. They are just three or five minute calls that only allow you to say where you are and how you are. I called my aunt and uncle and told them my current location and the ways for them to add money to an account so I could call them. I also contacted Michael, (my editor at the Washington Blade), and Hugo Landa, the director of Cubanet, an independent news site for which I worked from Cuba.

I poured all my frustrations on them. The words barely came out as my eyes were two springs of tears. They tried to calm me down as best they could. They told me that “each case is different” and not to worry because they would not abandon me. Their words comforted me a little bit. They were a small ointment for the open, latent and bleeding wound that Louisiana was giving me. I hung up while trying to erase the anguish from my face. I don’t know if I made it. I didn’t want to appear weak to everyone else, although I imagine my comrades from Tallahatchie were in the same situation.

I was hungry at night and the rest of the Cubans must have known that from their own experiences. They invited me to a meal they made at around 8 p.m. They served me some rice and soup, for which I will be forever grateful, in a glass. It was a delicacy from the gods in order to not go to sleep hungry, which is one of the worst sensations in life.

Not a country school or a high school (May 4, 2019)

Almost everyone in Bossier sleeps after dawn. I don’t feel much better than yesterday after waking up for the first time in this prison. The fatigue the long journey caused has of course diminished and my eyes no longer look so swollen and red from the insomnia that I suffered. I made a visual tour around me to adapt to my new “home.” Everything indicates that I will spend a long time here. The pod is much smaller than the one in Tallahatchie. It has a capacity for 80 people and is divided into three-level bunk beds and single beds.

My bed, bolted to the floor, like all of them, is one of the closest to the bathrooms. Fortunately, no unpleasant odors emanate from them, as the three urinals and four toilets work perfectly. What a relief! The bathroom area is the only one that remains fully illuminated at night in order to prevent falls when we go to do our business. It is also the only place in the pod where there are no surveillance cameras in order to preserve privacy. It is an area visible from the control tower, so “privacy” is misleading.

Three cameras that provide a 24×7 overview of the room guard the pod. That privacy thing here is a myth. The cameras see you when your comrades don’t. It’s a very uncomfortable feeling to be watched all the time, but I get it. There is no personal time here, not even for the most basic needs. There are no partitions between the toilets or the urinals, which are all made of metal. The showers are also located next to each other, without side or front curtains. It is simply a dead end corridor, where you have to bathe communally.

There are five sinks with five mirrors between the showers and the toilets. There are five telephones located next to the door that a company called City Tele Coin operates. It’s acronym, CTC, reminds me of the inoperative Central de Trabajadores de Cuba. I just hope it is more useful and functional than the Cuban organization.

There are also two touch screens through which messages and video calls are received and sent that very close to my bed. They also have several applications for games, movies and music, although, of course, everything has to be paid for. One hour of listening to music, watching movies or playing Candy Crush costs $3. Highway robbery!

We have two microwaves and two televisions. The smallest one, locked in a transparent plastic box, is for watching television, and the largest one only shows slides with ICE information in several languages. There are two non-working drinking fountains and a cooler for ice at one end of the dorm. We only wash glasses, spoons and cups with water in a deep, silver metal sink. Garbage goes to two bins without covers that are located at both ends of the dorm.

Many Cubans would say this pod is similar to country schools or dorms for high school students, but we have air conditioning here. Water is not scarce and we do not study or work. It is, however, a compulsory stay that is unfair and, above all, cruel.

They feed us on trays with tasteless and poorly cooked food as they do in Cuba. We are under a quasi-military regime, subject to punishment and mistreatment. While I lived on the island, I only went to school in the country for a few days, which, by the way, was horrible, and I never lived in a high school. Maybe life is now collecting all those debts from me. I want to think that is the case.

Exploring Bossier (May 6, 2019)

As one of the “new” people, many have come up to me to tell me about the rules — including those that are unwritten — that govern this prison, or to explain how the prison works. That is not why these mandates are less important. They are, in fact, golden rules. Don’t “screw up” or suffer any punishment for doing something “prohibited.”

One of the most ruthless rules is they get rid of the bedsheets at around 7 a.m. every morning. One of the officers on duty forces you to wake up by shouting, “Wake up, make your bed!” and make the bed with the blanket across it, as though it were a military academy.

There are those who are fast asleep and do not listen to orders or simply refuse to lose their warmth so early in the morning, when the cold is bone chilling and sleep still lingers. I honestly can’t sleep after losing the comforter, but the vast majority of those who don’t have long sleeves that cover their arms and hands cover themselves with padding. Others cover themselves with a sheet or a towel to continue to sleep.

The officers once again enter to check that no one is covered. It sometimes does not matter whether the bed is not perfectly made, what matters is that no inch of your body is covered by that black blanket. Those who do not comply have their bedspreads removed and thrown into the hallway outside the pod. They are not brought back until after 4 p.m. when we can once again cover ourselves with them.

No one understands this rule, but we all suffer bitterly from it. I asked the jail’s warden during a later interrogation — about which you will later know why — about this inhuman behavior and he told me that they did it so that we could sleep at night. They did not achieve their goal because most of us continued to sleep in the fetal position and others covered their heads in a fruitless search for heat. The air conditioning penetrates every pore of my skin and freezes me to the core.

We suspect the officers lower the temperature in the morning which, combined with the lack of blankets, leaves us in a very vulnerable situation. It’s like living in a daytime winter, because they lift the blanket restriction in the afternoon.

The bathing schedule also begins at around 4:30 a.m., although we are also allowed to take a shower after breakfast (at around 4 a.m.) until approximately 6 a.m.

The water is extremely hot and the steam rises to form a cloud on the bathroom’s ceiling and reaches the pod, which around that time becomes warmer. The toilet area is painted an ochre color, darker than the rest of the dorm. The walls and the floor are covered with a kind of thick layer of waterproofing, which does not allow water to penetrate the walls or the floor. There are rectangular grids in the floor that allow for it to drain.

We all bathe in flip-flops for fear of fungus, hair, accumulated soap, black mold that forms along the edges of the walls and even semen, which more than a few “discharge” when masturbating if they manage to bathe alone. It almost always happens in the mornings, when the showers are empty because most people are still sleeping.

The Hindus are always the ones who initiate the evening bath. They sometimes spend more than half an hour there talking, joking and laughing, as if they were in a sauna. Bathing is one of the few pleasant moments here. Most of us take our time under the stream, trying to relax, putting our thoughts in order, or just leaving our minds blank, reassessing our lives and perspectives.

Some take it as a moment of fun: They play like children throwing cold water or ice onto each other, while the bathroom for others s the perfect curtain to hide the tears and the suffering repressed for so many months. It is a mixture of both for me that also mixes with the discomfort of using a shared bathroom.

I have only bathed communally a handful of times in my life, but it is something, like everything in life, to which I have gradually become accustomed. We bathe in long white cloth underpants that they give us when we arrive. They also sell them at the commissary.

We call these undergarments “libido killers” in Cuba because they annihilate any “sinful” desire. They are so demure and old-fashioned that only the elderly use it. I guess they seek to create that same effect here. We all seem old and retired with no life or sexual desire.

Shopping ‘online’ from jail (May 8, 2019)

I was already able to shop at the commissary that City Tele Coin operates after they entered the money I had in the account. I received a receipt that corroborated it. We place our orders through tablets or on the two screens on the wall.

The commissary items arrive twice a week: Tuesday and Friday, the same for the four immigrant dorms. Your order is ready before you get to the window, where there is a woman and several prisoners who do the heavy lifting serve you. It’s like shopping online, an experience I’ve never experienced before. What a pity that a jail is the first place for this!

This country is so modernized that you can even shop online from prison. There is of course not everything one would like in the commissary. It is a selection the company makes to meet the most basic needs, mostly food and hygiene.

The prices are super high, to the point that a Maruchan soup costs $.85. We bought them in Tallahatchie for $.40 cents and I have been told they only cost $.10 in the supermarket. CTC charges eight times the soup’s original price, but there is no other way to shore up Bossier’s flimsy diet. They know it and take advantage of it.

But you don’t just have to buy soups, soft drinks, salt, mayonnaise or cookies. We also have to buy all of our essential items such as soap, shampoo, underwear, socks or toothpaste. A bar of soap, which the box says is forbidden to sell individually, costs $1.50. This prison is the only place where I have seen immigrants have to buy their own toiletries. Hygiene products in the previous prisons through which I went and where my comrades have remained are complimentary.

The only thing they give away here is toilet paper, a roll every Saturday. This prison also does not provide us with razors. They say it is “a security risk.” They claim the blades can be used to injure someone or for self-harm. This does not happen in other detention centers. They gave us the razors in Tallahatchie and in California. Many prisons require identification to get one and we do not receive the “identity card” back until you return it in perfect condition.

We have to remain unshaven all week until Saturday or Sunday comes when we can shave with electric clippers, which several comrades have bought at the commissary for $38. The weekend is the only time we have the right to shave or get a haircut. The officers keep the machines during the week and we do not have access to them.

This is life at Bossier: Full of difficulties added to those of the migratory process that is already extremely stressful and complex. But they say that one adapts to everything, although I am still not used to getting up at 3:30 a.m. for breakfast, eating lunch at 11 a.m. and eating dinner at 4 p.m.

Laundry service to wash the whites is on Tuesdays and Fridays. The rest of the clothes that we wear aside from the only yellow uniform that we have are white: Sweatshirts, underwear, socks, towels. They change our uniforms on Thursdays and Sunday, while they wash our sheets on Sunday. The laundry is lousy. The clothes usually come out dirtier than they were before. The garments arrive wet and we must be put on any surface to dry.

The white sheets have already faded, and their color now varies between gray and a “brownish” tone, the one that fabrics acquire when they are washed without care and are extremely used. God knows how long they have to live! Some look very battered with holes, stitched, tied, cropped, stained and almost transparent. Any of those can arrive every Sunday when they make the changes. You will receive the “best” if luck is with you, but they are not the most common. That sheet will stay with you during the coming week.

You hold on to it or try to change it if it’s bad. The same happens with the blankets, only that they go to the laundry once a month. When the blankets come back “clean,” you no longer know which one you had before. They are all in a drawer and we form a line to receive them. A prisoner hands it to us one by one. It is the same with the sheets. You only have to try to get an officer to change a comforter in poor condition if he is in a good mood. There are those who prefer to secretly “change” it from someone else. That’s the situation here. I live in a jungle and its survival of the fittest.

An international hostel (May 11, 2019)

The ethnic makeup of my pod is a concoction. I live in a multicultural pod; where various traditions, customs, religions, races, languages, temperaments and even smells intermingle. I sleep on one side, next to three Hindus. I had certainly never interacted with people from India before. They, like everyone, have their particular characteristics, but they don’t bother me.

I have actually developed a certain empathy with them. We communicate in broken English on both sides. They, in turn, try to teach me words and phrases in Punjabi, their native language, as almost all of them come from the Indian province of Punjab. Punjabi is extremely difficult and they have fun teaching me expressions that they make me say to their classmates in the middle of the night. And I repeat them with no idea what I’m saying. They all die laughing.

These “lessons” generally take place when we are already in bed and I also try to teach them the basics of Spanish. They already know some words, and of course they are the most repeated curses in the pod and the occasional greeting. Some manage to get through those words and string together some sentences with difficulty. They teach me “bad words” in their dialect as they repeat “bad words” in my language.

Communication here is not just based on a universal language, such as English. We use mimicry, we stage situations and some people even draw what they want to say to achieve a clear understanding.

My level of English luckily allows me to speak the basics; the same with the Hindus as well as the Chinese, Sri Lankans, Africans, Bengalis, Nepalese or Syrians. The most common nationalities are Cuban and Hindus, two groups of more than 20 immigrants who sometimes gauge their strength in efforts to lead the pod.

There is also a significant group from Central America: Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua are the countries represented the most in this ajiaco of exiles. While I am cultivating friendships with my new “roommates,” I spend most of the time with my friends from Tallahatchie, especially with Jéiser, a Honduran who is only 18-years-old with whom I have a lot in common, especially because we are both gay.

I have honestly achieved a certain closeness with the Central Americans that I don’t have with the Cubans. I manage to identify more with their ways of acting, even though we have certain cultural differences. They are more polite, simple and kind and obviously less vulgar and noisy. But successful coexistence is about tolerating everyone equally, with their defects and virtues. That does not, however, mean that they approve of many attitudes that seem entirely despicable to me. We all live together in this international “dorm” with the same purpose and nothing and no one should divert us from that.

The outside world from behind bars (May 15, 2019)

Going outside has been one of the most effective treatments for my emotional well-being since I’ve been in this process. I went to the “yard” in Mississippi every day at different times. There was a schedule for it on the cell door and it was generally followed, but not here.

My comrades tell me that recreation in this jail is almost as rare as Halley’s Comet, which passes earth every 75 years. Another blow, as if there weren’t enough already. They took me out to the “outside world” a few days after I arrived.

I have to go through a corridor where I see the rest of the three pods in order to get to the yard. Mine, C-3, is the first one on the left. I then see C-2 through a large window and pass the doors to C-1 and C-4. We all wave and shout at our friends in the other dorms at that time, but we should not be very excited because this type of communication is prohibited and they can, as punishment, reduce our recreation time or simply eliminate it.

I had to write my name and my Bossier ID number on a sheet that the officers leave outside the pod before I left. You won’t be able to leave if you don’t fill it out, although there are several officers who are flexible. Some let you sign up just before you leave; others do not even check the list, while a few look with a magnifying glass and check if you are on the page.

They tell us that again before leaving, and report it to the control tower. The heat suddenly hits me when the last door opens. The sun, the light, the fresh air, the smell of the wet grass, a mass of sensations invade me when I see myself outside of that concrete square where I stay 24×7. I walk down a sidewalk to a kind of tiny patio. I’m in the outside world, but surrounded by chain-link fences with barbed wire on top.

The perimeter contains a concrete square and there are three wooden benches and two bars for exercising around it. Gigantic towers with 10 spotlights on top of them border the “yard.” They illuminate the installation. They bathe the jail’s outside environment in a yellowish color after nightfall.

There are no bathrooms, no telephones, no exercise equipment and no water, much less a shade in which to shelter in the courtyard. The officer who is protected from the sun by a metal roof is the only one who has that privilege. He guards us with a shotgun. I’m not sure if it has real bullets or rubber ones, but it is still intimidating. Some carry it in their hand all the time in a constant state of alert, as if a breach were possible. Other guards just put it in a corner and start looking at their cell phones.

It is healing to be around the landscape. Bossier is in the middle of nowhere, deep in the American South and surrounded by splendid and expansive forests. The trees are located a few meters away, but the grass around the “yard” is perfectly mowed because they can easily pursue those who try to escape if there is a breach. The vegetation stands out in different shapes, sizes and shades at the end of the lawn. They form a dense green boundary in which I am told deer, squirrels and wild pigs live.

This natural sight gives me a bit of spiritual calm. That’s why I never stay in the pod when they call recreation. Once you leave you cannot go back inside until they order it and you lose the opportunity if for some reason you could not leave on time because of a medical appointment, court or a meeting with a lawyer. I close my eyes once I am in front of the fence and take gigantic breaths of air to disinfect my lungs from that still, machine-generated air of that enclosure.

The temperature is not too hot and the day gives me a very blue sky through which several planes fly, leaving that thin contrail by which they can be tracked. My comrades talk in a group around me, others take the opportunity to walk while a few kneel in intimate prayer. They put their hands together and some rest their heads on the fence, as if trying to fit through its tiny holes.

This time we are the only ones from my pod, but I have been told that they sometimes allow several dorms into the yard at the same time. That allows friends who were separated to meet there.

You can also see through the bars a road where few cars drive past in two directions and there is a maximum security prison right out front. A minimum security prison is a little further to the left. The road to the right of me leads to a little town called Plain Dealing.

It is wonderful to once again feel the sun’s rays on my pale skin, the wind that slowly rustles the branches and the sweet song of a little bird while flying from a tree to a pole with a surveillance camera.

“Life does not stop, the world continues its course,” I tell myself, even though I feel like I will spend the rest of my days in this prison.

Going out to the yard helps me remember that there is a better life waiting for me out there and that I must keep fighting to achieve it. A few people have the opposite reaction. Visiting the “yard” becomes a bittersweet drink, seeing freedom so close but at the same time so far away. It is such a brutal irony that some cannot overcome it and flee from it, hiding in the pod. They prefer not to get out of the “oyster” so they don’t get excited about something they cannot have.

I see an officer approaching in the distance and the guard with the shotgun yells: “Line up!” It is a sign that time is up. I’d say it’s been half an hour, maybe a little less. Time seems to run out faster when you enjoy it the most.

I’m an ‘alien’ (May 23, 2019)

I received a document a few days ago that notified me about my first court date. It will be May 23. It also included a phone number that has information about the process. Detainees can find out the date of a hearing, its result, and how their appeal process is going by dialing the number 6000 and following the instructions. The point is I was already warned. I had my first appearance before the judge only 20 days after I arrived in this place.

My comrades had told me a little about the immigration process to which I will be subjected and what would happen in my first hearing. I shouldn’t be nervous because nothing important would happen this time.

They took me, along with eight other immigrants, early in the morning to a tiny room with a door marked “attorney,” which is evidently used not just for legal visits, but also for court hearings. An officer named Crawford was waiting for us inside. A television, a table with a few seats and several stacks of documents are in the room. The hearing is through video conference. The court is in the town of Jena.

They turn on the television and a man in his 50s with brown hair, a large build and glasses appears. He is wearing the classic black robe and is sitting at a desk surrounded by papers and a computer with the American flag behind him.

He introduces himself. He tells us through a Spanish interpreter that he is Immigration Judge Grady Crooks and that we are in an initial hearing to learn about our rights as immigrants.

“You are in immigration court because the government believes you are here illegally and we will decide if you will return to your home countries in a three-part process,” the judge said.

The court will first decide if we are here illegally. After establishing if we are illegal, it will seek to determine if there is a way to legally stay in this country. (This is the second stage.) The court will finally decide if we are eligible for some form of release. Crooks says this process takes 60 to 90 days from today until the final hearing.

He then read to us the rights that we have, including the possibility of representing ourselves or hiring a lawyer at no cost to the government at any portion of the process. We may also present evidence, including testimonials, documents and photos in support of our petition. It is also our right to examine and challenge evidence, as well as having the possibility to appeal the court’s final decision if we are not satisfied with it.

“You are aliens who came seeking asylum at a port of entry and therefore do not apply for a bond,” Crooks explained. He then told those of us who were afraid to return to their countries and were interested in applying for asylum to raise our hands and then administered an oath. Only one of us did not raise their hand and the judge affirmed that he was then going to speak with each one of us individually.

“To receive asylum in the United States, the applicant must demonstrate that he suffered persecution or will suffer in the future, based on his race, religion, nationality, political opinion or because he is a member of a particular social group,” Crooks explained. “To be protected under the United Nations Convention against Torture they must show that they would be tortured by someone their government cannot control.”

He said at the end of this hearing we would have the I-589 asylum form and broadly explained how to fill it out. Everything has to be in English and each document has to be translated into that language. They gave us two yellow envelopes with the addresses of the court and the government. The original must go to His Honor and one copy goes to the government. We must keep another copy.

The judge asked if we had questions about the process and we explained the parole situation. We informed him that we had been granted the possibility of obtaining a parole, which is nothing more than the conditional release that can be granted to an immigrant who presented themselves at a port of entry to request asylum, after passing our “credible fear” interview in Mississippi.

This document’s objective is to be released in order to complete the asylum process in freedom after an ICE officer interviews you and you have the required documents, but none of that has happened. I went to the judge myself to inform him the interview never took place, even though my family had sent the documents on time with only one day to do so. They only sent a document that said parole had been denied without any further explanation.

Crooks said he had nothing to do with it. It was ICE’s responsibility. He only took care of the bonds for which we are not eligible.

“As arriving aliens, you will remain detained during your processes,” he ruled.

My soul froze. The judge thus confirmed all the comments in the pod about parole denials and sentenced us to a prolonged and unjust confinement.

I swallowed hard and tried to calm myself down. We started talking to each other and decided that we would not be defeated. We were not satisfied with the judge’s answers and would fight as long as possible in search of some encouraging news. Someone claimed people got parole in other states, but everyone here was denied outright.

“This only happens in Louisiana?,” asked one hearing attendee.

“The parole decision has nothing to do with Louisiana. That decision was made before coming to this state. Parole has nothing to do with this court,” reaffirmed the judge as if to close the matter. We then immediately went to speak with him individually because none of the nine of us had a lawyer with whom we could consult.

Crooks in my personal interview asked me a few more specific questions. I answered some of them in English, so he figured out that I knew something about the language.

“Can you write in English?,” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Could you help your counterparts fill in the form? You have a skill that is in high demand now,” he said.

“Yes, of course. I will help them,” I said.

He looked at his calendar and said I should send the documents on June 5 and that my second court hearing would take place on June 13.

“Go to work. We will see each other soon,” he concluded.

The training begins! (May 28, 2019)

I began to write the answers to the questions that the asylum form requested after I carefully analyzed them. The space to write is miniscule, so I will, to the best of my ability, use my capacity for penmanship that I learned during my career. I wrote and rewrote. I wrote it from scratch again. I edited it to make it perfect every time I read it. Here I am. The more I search, the more I find. It is the formal request for asylum, the one that the judge and the government will read. Everything that happened to me has to be there in detail.

I collected several articles and documents while I was in Mexico that prove the persecution of the independent press in Cuba. I also managed to obtain several letters from the editors of the media outlets for which I have worked that attest to my performance and corroborate my story.

There will be 40 pages in each envelope after I select them, so I need a total of 20 stamps that I must buy at the commissary. A stamp must be affixed to every four pages. Each book of stamps costs $5.50 and comes with 10 stamps. Everything must be ready before the judge’s deadline.

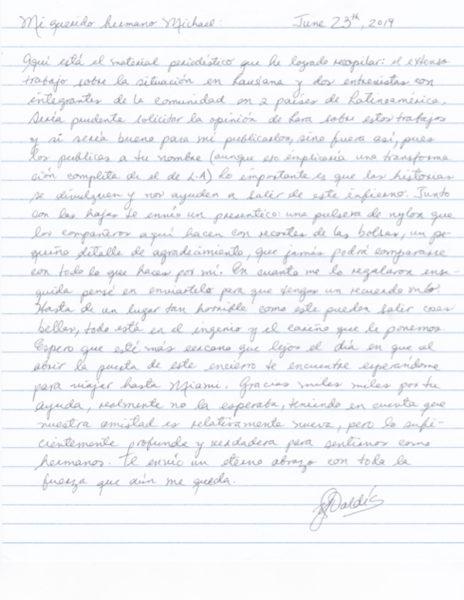

Michael over the last few days has spoken to me about the need for a lawyer. I did not think it was necessary at first, but seeing the situation as it is, I believe that the work of a man-woman of law is crucial because I don’t know the ins and outs of this process and immigration laws are extremely complex, even for the lawyers themselves. Trump’s current policy is highly anti-immigrant and one must have all the necessary support possible.

The point is I don’t have the money to hire a lawyer. Michael, who has become another brother to me, tells me not to worry about it, but I do. I sometimes think I am abusing his trust and friendship. He does not take “no” for an answer and said that he would take care of everything. I have no choice but to accept it. It would also be stupid and rude to reject that helping hand, which many would like to have, extended with such affection and concern.

I will then take care of paying off the monetary debt. Michael has promised me and my family that he will get me out of here and he does not know how that fierceness motivates me every day. It makes me feel secure and fills me with confidence. His unconditional support has been fundamental for me. I feel protected by his hope and strength, and it makes me more courageous so I can face everything and everyone.

Michael a few weeks later told me that he had already spoken with a lawyer who would take over my case. He will meet her soon. Her name is Lara Nochomovitz and she is one of the few lawyers who regularly visits this prison. I had already heard her name several times because she represents many people here. I had already submitted my I-589 form and several documents to prove my case by the time I first met with Lara. My second hearing was very close.

I can see something in Lara that tells me she is more than a legal representative. I had the feeling that I could trust her and that I would become her friend. She told me after I gave her my “credible fear” interview (ICE gives us a transcript of the telephone conversation), my asylum form and talking to her about the reasons why I had come to the United States that my case was powerful and she was willing to fight with me. Lara was also frank and direct.

“We will not win asylum because of the judge we have right now. I will prepare all the documents and we will work together for a perfect hearing to win the appeal,” she said in a strong tone, which left me feeling somewhat hopeless, but at the same time I felt that I could trust her.

She never gives her clients false hope and she speaks the truth, however harsh it may be. She always prepares me for the worst and in part I thank her because that is how I am arming myself with a shell that will cushion the blows to come. She asked me if I was willing to fight to the end and I replied, with sadness showing on my face, that I couldn’t return to Cuba.

The asylum process typically takes between three to four months and the first appeal takes about six more. Ten months in freedom pass like a flash, but in prison they seem like an endless storm that not everyone is able to bear. I just hope I have the necessary endurance and capacity for it, and I must build it myself if I don’t. The training begins!

The ‘wonders’ of Bossier (June 3, 2019)

Life here is sometimes as precarious as in Cuba. Necessity makes us find one, two and even three uses for the same thing that we would throw away in the outside world without thinking. Various comrades’ ingenuity is as admirable as that of the Cuban innovators who create something from nothing and reuse even the unimaginable because of this socialist underdevelopment.

Comfort is the one thing that does not exist in this prison. It is a forbidden luxury that simply does not fit into the most basics of living. We have to settle for the cheapest food, products and services since we are a burden to the government. You don’t have to be very smart to figure that out.

Based on that premise, our creative abilities skyrocket. One of the most popular inventions is showers, although almost all of us refer to them in our prison Spanglish. “Las showers” help us in the bathrooms, where the water that falls is a harsh and hot jolt.

The opening through which the water flows is so small and comes out with such pressure that it feels like the sting of a bee protecting its hive when it hits my skin. The solution they found was to make a contraption, which is nothing more than two pieces of plastic put together. A hole is generally cut first on one side of an empty cream container, a shampoo bottle or any other bottle. The second piece goes through the other end, which is usually another container, which could be one for seasoning with the lid open.

A container of salt or garlic powder, which they sell at the commissary, is best for this purpose because its lid has small holes through which the spices come out. The water instead falls over my body like a warm waterfall, allowing me to bathe without shock. The water therefore achieves the effect of massaging my skin. It is by far the most popular invention because, incredibly, it also acts as a hot water heater. Your shower will heat up a bit more if the water isn’t warm enough.

Showers must be kept out of the reach of prison staff. They do not hesitate to collect them and throw them in the first garbage can they see because it is another one of the restrictions here, although it does not make any sense.

Another invention is the yarn that some make with the patience of weavers. The raw material is the bags to line the garbage cans that they bring to us every morning. They obviously make the yarn out of the unused bags. They take out thin strips that twist to form a kind of cord. They then stretch that cord to form a thin but extremely strong thread, which also serves as a rope to hang clothes.

Only one or two people in the prison can do anything else with that nylon line. My friend Erick is one of them. He learned in this same place to weave these threads and make bracelets, necklaces, rosaries, crucifixes and even rings out of them. It is like a nylon jewelry box. There are probably not many in the world. He weaves the threads into various designs with great patience. He has achieved such a level of perfection that he can even place names, initials and figures on the bracelets and necklaces.

He combines black and white bags with candy wrappers of various colors and thus creates bracelets worthy of admiration. He usually makes them for free. He rarely asks for anything in return, even though he doesn’t have an instant soup to warm his stomach at the end of the day.

There is a Cuban in C-1 who also makes bracelets, but he charges two Maruchans for them. I ordered one for Michael. They are one of the few beautiful things that comes out of this evil place. I once tried to send a bracelet to my friend in a letter, but those items are considered “contraband” and are not allowed out. I don’t know what harm a nylon bracelet can do out there in the world.

There was a time when wearing bracelets was a crime. It bothered the officers and they would probably take them off if you went to the doctor, for example. They have recently realized that they are harmless and some officers even wear them while they are working. We give them away to those who like us. I now remember David, a friendly officer who babbled some words in Spanish that he learned through repetition, who had two bracelets on one of his wrists.

They are perfectly washable and dry very quickly because they are made of nylon. Erick gave me one with the word “freedom,” which I always wear on my right wrist because that is what I want for my life.

My third favorite creation is puddings. I have not made any, because they require several ingredients and are honestly too much work. It was obviously a group of Cubans who I saw make them for the first time. Who in Cuba has not eaten pudding? The Hindus ordered one to celebrate one of their birthdays, and I saw the process up close.

They poured the dessert that they give us at a meal — what we call “marquesitas” (a kind of panetela) in Cuba with a layer of cream on top — into a bowl. That works like the dough to which they add milk, chocolate, peanut butter and sugar. You can also add oatmeal, cookie dough, fruits and even cereal. It is a rare combination of sugary food exists.

Everything is mixed together form a doughy and homogeneous mass, which is cooked in the microwave for approximately 40 minutes. The result is a dense pudding that is cream or darker in color, depending on the ingredients used. Some Central American, Cuban and Syrian friends often make them for dessert and they sometimes give me a portion. They inevitably remind me of what my grandmother made when I was a child with a little bit of milk and a few eggs, but with plenty of bread and love.

I am a fervent fan of this “wonder.” It was the dish that cured my hunger before going to sleep for several months. It’s the closest thing to a hot meal from home that most of us here have. Erick, my inseparable companion, and I prepared the soups and we added mortadella or hot dogs, carrots or green peas, rice with chicken or croquettes, depending what we could save from the day’s meals. We added a little water to hydrate the noodles and increase the amount of food.

We preferred to eat it dry, like spaghetti with vegetables and some chicken or chopped meat. We also seasoned it with mayonnaise, hot or barbecue sauce. It seems like a nonsensical jumble of food when we describe it like this, but it turned out to be a fairly decent meal. The very need to have something better drove us to eat what was at least something substantial that filled us.

We had to eat the cold, raw soup, with the noodles softened by water on more than a few occasions because we did not have a microwave. It was either taken away as a form of collective punishment or was broken. I joke with Erick every so often that I will write a cookbook with 50 different recipes for making a Maruchan soup when I get out of here and will distribute it among the prisons. It would surely be a bestseller.

My family of choice

There is a very famous phrase that says family is not chosen. We can form one with friends, couples, neighbors and even in-laws. Many times these people become more important than a person who carries your own blood. This is not my case. Neither in good times nor in bad times, like this one, where people are really tested, do I have complaints about the family that has embraced me or the one that I have created over the years.

They have all been very aware of me and they have not hesitated to prove their worth, even with the smallest of my requests. I feel lucky. One of the good things about this confinement has been the friendships that I have made and that I will remember forever, even though these fatal circumstances have put us in the same time and place.

The cruel thing about these friendships is that they tend to be too ephemeral; cut off by detention center transfers, deportations, voluntary departures and, in very rare cases release into this country with asylum, bail or any other way.

Despite this, some have had a deep impact on me, to the point that we consider ourselves “brothers” or “carnal,” as Central Americans call their brothers. My first brother by choice is not physically within these walls, but his company is present every day. Although we have been friends for a short time, a single meeting was enough to solidify this brotherhood for which I will be eternally grateful.

Michael has been my salvation, my guardian angel, who has donated his time, his affection, his money and his trust. He has made the newspaper where he works available to me so that I can grow professionally and personally. I just hope one day I can repay so much dedication.

The first friends that this immigration gave me were in Tallahatchie, where I spent a month for my “credible fear” interview, which is just the beginning of this long process. You naturally meet many people while living in a collective pod, but you end up having true empathy for just a few of them. I lived in the JC pod with another Cuban during my time in that prison, but my closest friends were Darwin and Brittany.

We were unfortunately in different groups when leaving for Louisiana. I was first transferred along with Jéiser, another gay Honduran who almost joined us when we were leaving Tallahatchie. Darwin and Brittany remained behind, but they had the same destination, the state of Louisiana.

Michael recently sent me an article about Darwin’s situation at Jackson Parish Correctional Center. I later found out that he and his partner had won asylum and were now free. They were already living in the home of some people who welcomed them in Colorado. I also heard that Brittany was released before her final asylum hearing and she was also in Jackson with Darwin.

I sadly learned that they were suffering discrimination and abuse because of their sexual orientation in that detention center. Luckily, they are already free. It was a great relief to know that they were victorious in this whole process and that finally no one else will persecute them for loving another man.

Once here in Bossier, my friendship with Jéiser has strengthened to the point that he was the only person in the pod who knew about my breakup (with my boyfriend Lester) and gave me his full support. I realized during those days that I had gained a friend who was even willing to fight for me if necessary. He was the voice of reason in my wounded heart.

Our communication and trust allowed us to give us mutual support in moments as difficult as the negative response to Jéiser’s asylum or when his mother, who lives illegally in this country, insulted him on the phone because she found out that he was gay. You sometimes can’t find the right words to comfort a friend in such a situation. A hug or just a shoulder to cry on, however, is all that is needed. And there I was for him.

I sadly confirmed that Jéiser’s mother was not worthy of the son she had, who survived a trip on La Bestia, the freight train that transports immigrants across Mexico, and had survived in this country’s prisons for several months without ever receiving a penny from her, not even to call her. Stories like Jéiser’s are often repeated in this confinement. They confirm that for some, the blood family is nothing more than a fleeting memory to know simply from where we come.

Friendship with this Honduran later brought closer ties with other Central Americans such as Kevin, Erick, El Papi, José or Lenin. We exercised, played cards and had dinner together at night. I became so comfortable with these people that sometimes it was not necessary to ask for anything. Everything they had was also mine and vice versa.

Despite the immense cultural differences that separated us, I came to build a curious friendship with some Hindus, and I say curious because we communicate in butchered English. They mixed in Spanish words and I mixed in Punjabi words. It’s really a lot of fun when you manage to pronounce a word in their language and also coherently fit it into a sentence in Spanish or English.

I achieved that unusual spirit of brotherhood with one Hindu man in particular. His name is Suchil Kumar and he gave me a true test of friendship one afternoon when he was exercising with some Cubans. The guys told him that he had to stop “hanging out with me” if he wanted to exercise with them.

Suchil, indignant, told them that it did not matter, that there were other places in the dorm to exercise. I hugged him with emotion when he told me about it, and I knew that I had gained a friend who loved and respected me for who I am. He thus confirmed the homophobic and disgusting nature of some of his countrymen, at whom I could never look with pleasure again.

Suchil and I joked a lot with each other and with the rest. We tried one card game with another and the hours seemed to fly by. We sometimes met in the showers and shared several moments of true confidence until he was transferred to another pod. We only saw each other sporadically in the yard. He was deported to India and I couldn’t give him a goodbye hug.

Erick, with whom I began to relate through other friends, occupies another special place in my family of choice. We drowned our loneliness with a bowl of Maruchan when those friends were deported. Our friendship began “through the kitchen” and it was strengthened by shared opinions and similar mannerisms. Erick and I have a very similar temperament: Laid back and very cool guys, as they would say here in America.

He spends most of the day in bed playing “Con Quién,” a Latino version of poker, talking, watching a movie or sharing meals. I sit in his bed — that is our table — after receiving the lunch and dinner tray and prepare a snack before going to sleep.

For several months we made a soup each night for both of us, which tempered our hunger, but also unknowingly brought us closer and, of course, gave us a few extra pounds, which we are still trying to lose. There are several families of friends in C-3, who are united by common nationalities, language, culture or simple affinity.

Africans, Cubans, Hindus, Central Americans, Chinese and Syrians coexist in this community. The latter constitute a very unique group. To me it is the most sincere and united family. The Syrians at the end of the day prepare a banquet for its seven members, which includes a soup with ingredients that a Cuban would never think of mixing. They prepare coffee, fruits and everything they can gather from the day’s meals. They cook a black pudding for dessert whenever they can gather the necessary items and willingly share it with the rest of us.

They stay together all day talking in their native language that sounds really strange to the ears of Spanish speakers. The Sri Lankan tribe is the most peaceful of all in C-3. They want for very little. They are incapable of offending a fellow detainee or an officer with their own language, knowing that they will not understand them. They are everyone’s friends. They are the noblest and most correct beings that I have ever met in here.

I fondly remember Piké, a Sri Lankan who won his asylum case after an appeal, and with whom I often talked and joked. He would always stop by my bunk before going to sleep to say good night and say, “tomorrow is ours” with a smile. Every time he saw that I was down he would come over to give me words of encouragement and solidarity.

On the day of his departure, a fellow countryman said goodbye with tears in his eyes and we were all very happy for little Piké, because he had won a nine-month battle. It is bittersweet — happy and sad at the same time — when a friend leaves. My heart is torn because I lose a friend, but an innocent soul leaves this damned confinement for which I have few things to thank. One of them this family of choice that I have created and the one that I will create with those who will keep coming.

Confinement without you

(I received a letter on July 4, 2019, from Lester that ended our relationship of nearly two years. He swore that he still loved me. His words deeply hurt me, leaving me even more vulnerable in the loneliness of prison. Here is a version of my farewell letter.)

Since we said goodbye at the Havana airport on that day in September, I had not experienced such a profound sense of loss. I now remember that afternoon, punctuated by thunder and lightning, when I began to cry from the rain and invaded the atmosphere of darkness like a crude parallelism of my life.

My eyes were unstoppable rivers of sadness at the moment we said goodbye, while yours suffered a devastating drought. I knew that this forced separation affected you as much as it did me, but your stoic temperament prevented you from showing it.

The last picture I took of you, separated by the immigration line at the airport, was that of a man who was suffering, but refused to show it. A breakup letter from you after 10 months once again sows in me the same desolation of that goodbye.

I felt your words because for some time I noticed how your voice through the phone came with an icy tone. You were no longer the same and in part I didn’t blame you because it was me who took the first step that put a sea in the way. You proposed to give us “some time,” a “pause” in our sweet courtship of almost two years, but I know well that this is the most common euphemism for not hurting the other person too much when you want to end a love relationship. At least I have to thank you for that, but trust me: It didn’t work out.

Behind this proposal is the desire for a “friendly breakup” that rarely works out. I still accepted it. Could I do more? You must go hand in hand along the same path in a relationship. It is no longer valid when one of the two decides to take a detour.

Distance always marked our history: A four-hour bus ride separated us in Cuba, but that was not a deterrent to building a solid and resistant love. What’s more, we had plenty of love, even during my stay in Colombia and Mexico, but you banished me from your life with a tired apology when I needed you the most.

This farewell shakes the fortress here that holds me inside. You left me without love when your memory was the cure for much of my nostalgia. Despite this, I know that it was not an easy decision, because I managed to see the purest emotions in you and giving that up is never easy.

That’s why I can’t quite hate you. My friends say that you have erased my common sense and I am nothing more than a blind man who cannot see the reality in front of him. Perhaps time, with its healing energy, will give me back the tranquility and the reasoning that you have taken with you. Now I see everything without colors, withered … I have masochistic instincts and every so often I reread your letter trying to convince myself that you have definitely left and the anguish returns, which at times frees me from its punishment.

There is not a moment in the day that goes by when I don’t think about you or remember those caresses that are no longer mine. I swear I could still feel them, despite the distance that separates us. I didn’t want to think that this would happen to us when I got on the plane that rainy afternoon in September, but somewhere in my mind lived the phantom of the definitive separation.

From the bottom of my heart I want you to make all your dreams come true and that ours is that story that you remember when they talk to you about someone unforgettable in your life. I will try to heal the wounds of disappointment for when I embrace freedom again over here, to be healthy of you.

Prison journalism

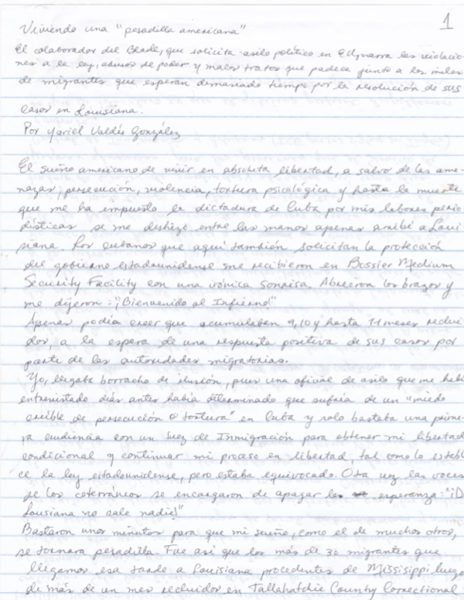

The idea of writing about Louisiana had been on my mind for several days. I had already done journalism in Tallahatchie by interviewing my friends Darwin and Britany and I was also thinking of sitting down to organize the ideas for those interviews around the situation of the LGTBQ community in Honduras and Guatemala, the countries from which my friends come. Their testimonies were terrifying voices in my ears, which could not understand such disproportionate evil or justification.

I wrote both stories, trying to relive the terror of both, persecuted by homophobic and soulless gangs, in no time. The articles also sought to make their cases visible and that it could also serve as evidence in their migration processes. I don’t know if they were able to see them at some point, or if a relative told them, because they were already in different detention centers by the time I wrote them and they were published.

I immersed myself in the bleak panorama before my eyes after I finished the interviews. As I was just getting to jail, I decided to talk with the oldest immigrants in this place to get a more objective and comprehensive perspective. I spoke with several of them, mostly Cubans, who told me about the complex situation in which they were plunged, some more than a year ago.

I asked about the immigration process, both parole (parole for those who enter through a port of entry) and asylum, which is non-existent in this detention center. I also wanted to share the conditions of Bossier, without a doubt the worst place I have been since my arrival in this country.

I wanted to provide a broad, yet detailed view of how immigrants live in ICE prisons. I had several brave people who were willing to tell me all their experiences, which would combine with the daily life of the place and my own feelings. I could not write an impersonal, distant story, as dictated by academic rules because as a journalist I was also part of the situation and I was suffering it firsthand. So the result would be a mix of two journalistic genres: The account and the reporting.

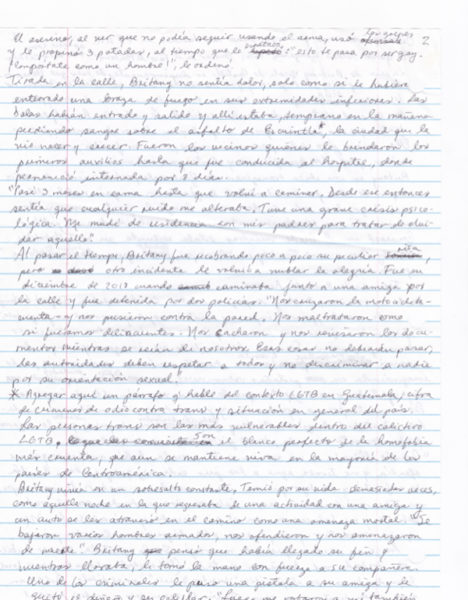

I spent several days listening to my comrades’ hardships and sharpening my senses to put this reality that increasingly grasped my chest on paper. I do not have a tape recorder, a cell phone or a camera, much less a computer here, so I went back to the prehistory of journalism, where everything was done with a pencil.

I wrote, crossed out, cleaned up the writing and edited it with the eyes of a proofreader. The sheet ended up being wounded by a playful machete, full of cut phrases, notes on the edges, reminders, arrows that redirect the reading and erasures in search of a better piece in each version. Sometimes I can’t even understand this ink jungle. I finally got material that in my opinion is worthy and extensive. I titled it: “Living an American Nightmare.”

I sent it to Michael by mail, the only avenue to which we have access for correspondence that officers thoroughly inspected before leaving. I also attached the two interviews with my Central American friends. Everything managed to bypass censorship. The officers fortunately do not understand any Spanish, so what they got their hands on was simply a bunch of incomprehensible words. I think it is the first time that knowing Spanish is an advantage.

Another result of this prison journalism was a story that I wrote about the journey that thousands of immigrants make every year on “La Bestia.” Those with whom I spoke were two Hondurans: I interviewed the first one in the detention center in California and the second was my comrade Jéiser here in Louisiana.

It remains an unpublished work that I keep in an envelope in my drawer. I hope it deserves to be published in the Blade or in any other media outlet that is interested in the immigration issue.

I had tried to keep a journal several times, but the words remained stuck in my mind and only a few listless, lifeless sentences came out. The tension in which my asylum process has kept me has prevented me from stringing together coherent ideas and I was unable to concentrate.

The narratives finally began to flow once I won my asylum on Sept. 18. The chronicles that detail what happened before that date were the result of an agonizing memory exercise like this one. The rest were born in the heat of events in the spirit of a campaign diary, because this is like any other battle in which I could also be seriously injured.

Writing for me is a relief within this confinement, a discipline that injects me with peace and distraction. It is, without a doubt, a productive way to spend time, one of the deadliest enemies within these four walls. These words are also motivated to overcome oblivion, that malicious vermin that erodes memories.

Living an ‘American nightmare’

My meeting with the warden

My article on Louisiana has been a success. Michael tells me that many people have read it and shared it on social media. Other websites have also aggregated it or have written their own versions of it and many people in Cuba already know where and how I am. My only fear is that my grandparents will find out. We have protected them because they are already too old and we must avoid unnecessary suffering and worry. It won’t solve anything if they know.

The Blade will have my story on the front page. It is a great honor for me, as a Cuban journalist and exile. Being on the cover of a newspaper has always thrilled me. Another article of mine had already headlined that gay weekly in the American capital, but undoubtedly this one will acquire other dimensions, which I hope will be positive for me and for those of us who live in Bossier. So it was.

One afternoon an officer called my name at the entrance to the pod. I picked up my documents thinking that it would be a legal visit. I was, however, brought to the reception area where I was greeted by another officer who began to speak to me. His first question was whether I spoke English. I replied, “a little.” A nurse of Mexican ancestry who was standing next to me would assist me if my vocabulary was not up to the level of the conversation.

With a serious tone, the warden told me that he had received a complaint: The human rights of immigrants in his prison were being violated. The person responsible was me and he had brought me before him to tell him about the “mistreatments” that I had suffered and that had reached the ears of his bosses who were obviously not happy with the bad publicity.

He had never dealt with me before. I wasn’t on any list of troublemakers or those who had not been disciplined, so he didn’t understand the root of it all. I had confused him. The warden looked concerned. His face revealed gestures of disorientation until I explained that I was a journalist. His face at that moment lit up and he came to understand what was happening. He was not aware of my article. He had only received that complaint that to him was baseless and full of lies.

We got into a debate on many issues with prison and the immigration process that I face here. He claimed that I (and everyone else) were just upset about the way things were going with the judge, but he couldn’t do anything about it. As the highest authority in the jail — only after a few minutes of conversation did I know that I was talking to the warden because I did not remember his face — he did have the power to change many of the absurd rules and racist and abusive behaviors of some of his subordinates.

He had not experienced many of the situations described in the article first hand, but therein lies one of the journalist’s functions: To cover other people’s problems and publicize them in search of an appropriate solution.

We each expressed our points of view on what we considered fair and unfair, rights and duties of immigrants in their custody and different situations that did not require a great effort to make our stay in this place more pleasant. I even complained about an officer who looked at us with the eyes of a crazy racist and treated us like subhumans who were inferior to him.

He said he would talk to him and asked about the officer who had brought me to him, a young man with weight and hatred to spare. I rated his behavior as “more or less,” so as not to put myself in such a difficult situation, and they all laughed.

The reception room where the interrogation took place was packed with officers. No one wanted to miss this unusual sight. They all looked at me with inquiring eyes, offended because I was “biting the hand that fed me.” That is why I had to measure my words with a ruler. I was entering dangerous territory. I could not forget my position: I am at their mercy, although the warden left me with the feeling that he is a rational and receptive man, or so he proved.

Our conversation progressed calmly, without rises in tone and in an atmosphere of respect, although the tension never left the room. I felt at various points that he understood my viewpoints and I had the remote illusion that some changes could come.

The warden, of course, did not like seeing his damaged reputation on the internet, and that made him defensive all the time. He tried to explain to me the causes of many actions, justifying the vile and ruthless behavior of some. He covered himself with a sheepskin before the wolf in front of him who had attacked his institution with “falsehoods.” There was not a second during the meeting in which he did not perceive the nervous pulses of my blood running through me from head to toe. I still managed to stay calm, despite the fact that my heart pounding in my chest proved the opposite.

The nurse asked me to write the title of the article — “Living an ‘American Nightmare'” —and the page where she could find it while the warden and I ended that conversation with a handshake. He took me back to my dorm with the same officer. An alert went off inside the prison from that moment on: They had an immigrant inside who could be heard on the outside. Inside me, on the contrary, hope was sewn that some improvements could come true. The most certain thing, however, was that I was forever marked as “the one who wrote the article.”

The adventures of Bamby … and others

My friend Jéiser’s nickname is Bamby. I don’t remember who named him that, but he is just as fragile and delicate as the Disney deer. He is so thin that he barely has meat on his bones to pinch. He combs his hair forward so it hangs from his head. It is shaved on the sides. Voluminous lips protrude from his face and his carefree and caring nature makes it almost impossible for anyone to get mad at him, including homophobes who can’t stand a gay man being too feminine.

In the pod, however, there are not many of those, or at least they do not bother to show it. Jéiser has cast his disturbing gaze on an American prisoner from the very day we arrived. He was a stocky Black man and his body was a canvas drawn in black ink from his face to his fingers. That was the only portion that was not covered in clothing, but we imagine his muscles under that uniform were equally covered by a layer of dissimilar patterns.

That Bossier tenant, like my Honduran friend, set his eyes on Bamby’s graceful figure as soon as we arrived in this place. Seeing him, his extra large lips whispered something to a fellow inmate as they shared sensual smiles. That ugly man contrasted with Jéiser’s clear image, so we always joke that if at some point the two coincide, that meeting would be as if a feather were dragged by a whirlwind.

But that, of course, was impossible. Despite the fact that we share this facility with convicts, they live on side D of the prison, in the opposite direction from C where we are. The only possible contact is with those who deliver the meals, help at the commissary, do the laundry or clean the hallways.

Bamby’s suitor is one of them. We cannot work here because immigrants have been stockpiled in this common prison. Work is reserved for inmates.

The prison romance was strengthened with the exchange of furtive signs and body language that both developed through the glass of the door and a window. The Black man spent minutes cleaning the same inch of the glass while he achieved some sort of communication with Jéiser. They sometimes have to resort to words because their mimicry sometimes failed them. There was another drawback: The language barrier was like an insurmountable wall that conspired against that romance, which became more intense with each passing day.

I entered the scene at that point. I became the lovers’ official interpreter and as such I began to translate and respond to messages written on scraps of paper, which after being read traveled down the drain at the request of the inmate, who feared that officers would find the prohibited correspondence.

This is how we learned that Bamby’s suitor had already been locked up for several years for drug smuggling and that he would soon return to freedom. The traffic of affections, meanwhile, increased. We wrote and received fiery epistles. Bamby and I had a lot of fun with it, and he gave us extra food from which we also benefited.

The suitor on several occasions managed to send Bamby trays full of food that included hidden pieces of fried chicken, desserts, sweets and of course messages with promises of affection of all kinds. This man was probably not gay and he would have never noticed Jéiser if he were in the outside world.

The heterosexuality of some who have been confined in a prison for many years, surrounded by only testosterone, can succumb to the carnal desires of whoever is able to satisfy them. They sometimes didn’t even have to go that far. The mere fact that they could satisfy those urgent needs of lonely men was enough to start a relationship full of morbidness.

But Bamby went much further. He began to share risqué words with that muscular Bossier waiter and one day while in the commissary line he admired him through the crack in the door to the room where he kept the cleaning utensils, making his erect penis happy. Beyond the pleasure that his own hand guaranteed, it was the presence of Bamby watching him just a few feet away without the barrier of a wall that catapulted him to a happy ending.

One afternoon, while the Black man was mopping the floor in the hallway, Jéiser was watching him from just a few feet away through the glass window. We watched something grow in his “lower zone” as Bamby whispered sexual words to him, sometimes not knowing exactly what they meant.

Bamby inside the dorm also stroked cocks hidden between bedspreads and towels. The Hindus, who live in another dimension of thought and are more open and laid back, let themselves be groped at the center of their pleasures and more than once in the bathrooms. The occasional voyeur witnessed how a playful mouth delved into the most intimate parts, while they were soaked by a morning shower when everyone slept in.

ICE could consider this to be a “sexual assault.” The agency has “zero tolerance” for any incidents of a sexual nature and there are posters in all dorms that announce it. This is very useful, especially to protect gay or transgender men from rape or abuse. But everything Bamby did was by consent, or rather caused by him.

The scenes starring Bamby weren’t a secret. It is difficult to contain the gossip in a place like this, where gossip is part of life. Some Central Americans, including another Honduran pretending to be gay in the eyes of ICE for his asylum case, complained about the antics of Bamby, who officers led to an interrogation during which they threatened him with isolation, with “venereal diseases brought by the Hindus” or with a change of dorm if he continued with his “practices.” None of that happened and Jéiser continued to do his thing, despite my advice to remain chaste. Discretion and obedience are not his virtues.

Bamby’s suitor did not appear for several days and we assumed that he had been transferred. It was not long before several food substitutes appeared to overflow the flaccid trays and the same notes with little hearts and phrases were once again there.

My experience, on the other hand, was much more innocent and measured. I exchanged several messages in the spirit of friendship with a convict who was also tattooed, dark-haired, and had a face and body worthy of admiration. I gave him a bracelet that my friends made and he returned the favor a few days later with an extra laundry bag with towels and a piece of chicken, which tasted glorious.

He got bored, and we stopped communicating after a few messages. The friendship was reduced to a few greetings or brief conversations when we met in the hallways. He admitted that he had also been locked up for drugs for more than four years. His incarceration had made him less social and he was now like a lonely ferret without much to say.

Sending and receiving the notes was also extremely complicated, since exposure to cameras and officers’ constant surveillance had to be avoided. I received the messages by hand a few times. The most common way was to put them on the trays when they left the dorm empty. It was dangerous traffic and it left me speechless several times.

A Salvadoran named Erick arrived a few months after deportation took Bamby from Bossier. Those who came with him affectionately nicknamed him “pajarita” and that is how we all began to call him around here. Erick was Jéiser’s understudy in every way. His life story unfortunately coincided with Bamby’s, so I had felt a sense of déjà vu several times.

I found myself writing messages another time, and this time I was rewarded with my own thank you tray. From time to time they change the inmates who cook, but that complicity between them and the gays is what remains intact. They hand out extra food in exchange for smiles and winks. It is sadly a way to survive for many here who do not have a penny in the commissary to buy a piece of candy.

Time for court

My second hearing was scheduled for June 13. The purpose of it is to check whether the asylum application and the accompanying evidence have reached the judge’s office and the government. From there they set a new deadline for the definitive hearing. Crooks had in his possession my Form I-589 and an additional 40 pages of evidence supporting my application.

I had my first contact with who would be my lawyer only a few days earlier and she recommended that I request more time to catch up on my case and work with a little less pressure. So I did it. I asked His Honor for a few more days because I was in the process of hiring a lawyer and was waiting for more documents from my home country.

Crooks gladly agreed and gave me over a month. My last hearing, also known as the hearing on the merits, would be on July 23. Lara, my legal representative, and I worked together on several occasions during that period. She contacted my family, colleagues and friends, who sent statements about my case.

My lawyer also located updated reports on freedom of expression in Cuba as well as on the situation of independent journalists on the island, who are increasingly besieged by a regime incapable of supporting criticism and left incapacitated by differences of opinion. Lara did a worthy job and I saw my file grow to more than 200 pages. She sent me more paperwork on my behalf a few days before the last hearing and she gave me more additional evidence on the same day it took place.

I did not feel safe on the day I sat down in front of the judge again, even though I had a solid case with a lot of evidence and preparation. My lawyer was not by my side. She was in the room with His Honor in Jena and I could only see them through a screen. Lara had told me that since the evidence had been delivered a few hours in advance, there was the possibility that the hearing would be postponed to allow more time to analyze the new documentation, but it was not certain.

My nerves got the best of me as soon as I entered the room. My heart was pounding like a drum in my chest and my hands succumbed to a tremor that, little by little, shook my whole body as if I were in the middle of a seizure. My brain ordered me to relax, but my heart raced through the depths of despair.