Books

New book puts kibosh on sentimentality of WWII films

‘Mercury Pictures Presents’ a fab read by acclaimed writer Anthony Marra

‘Mercury Pictures Presents’

By Anthony Marra

c.2022, Hogarth

$28.99/408 pages

“Mercury Pictures Presents,” a new novel by acclaimed writer Anthony Marra, brings the grit and pain embedded in the fabled days of yesteryear, close to home.

I’ll bet that when the news brings you down, you, like me, watch Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman in “Casablanca.” Or, maybe, Bette Davis in “Watch on the Rhine,” where Sara (Davis) supports her anti-fascist husband Kurt (Paul Lukas).

Old Hollywood movies set in World War II are our comfort food. It was good back then, we think, watching Victor Laszlo and Ilsa. The U.S. fought to rescue the world from fascism, and its citizens basked in freedom.

If only.

“Mercury Pictures Presents” puts the kibosh on our sentimental illusions.

The novel is set in Los Angeles just before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Much of it takes place at Mercury Pictures, a B-picture Hollywood studio.

Maria Lagana, a young Italian woman, works for Artie Feldman, head of the studio.

In many ways, Feldman would fit in well in a Marx Brothers movie or a funny TV sit-com. He’s a gruff, bald, sometimes crude, Jewish guy who names and displays his toupees. But a heart of gold and moral scruples are intertwined with this slapstick.

Artie and his brother Ned (with whom he doesn’t get along) came to America in the 1910s. They owned a movie theater named the “Titanic.” As you’ve likely guessed it didn’t do well. Still, they landed in Hollywood.Maria, Artie’s right hand, emigrated with her mother in the 1930s from Italy to the U.S. to escape Mussolini.

When she was young in Italy her father, a defense lawyer, took her on Sundays to see American movies. (They preferred Hollywood flicks over church.)

But these care-free excursions ended when her dad was arrested for defending anti-fascists.

Maria lives with her mom in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of LA where her elderly, commanding, but loving, always wearing black, Italian great-aunts live.

Maria’s boyfriend is Eddie Lu, a Chinese American actor, who would love to have roles in films of Shakespeare’s plays.

Maria is overwrought with worry and guilt about her father. He’s imprisoned in “exile” in Italy. Her dad’s letters to her don’t make sense. Because, like her correspondence to him, they’re bowdlerized by government censors.

“Mercury Pictures Presents” is operatic in scope.

Though much of the action occurs at the Mercury Pictures studio (which could go bankrupt at any moment), the story morphs from LA to Sicily to Utah (where a model of a German village is created).

As in real life, tragedy and comedy intermingle in the novel.

A Sicilian photographer escapes Italy (using someone else’s name). Prisoners in Italy live under deplorable conditions. The U.S. may be “the land of the free.” But because she’s emigrated from Italy, a country with which America is at war, Maria and her family must register as aliens. They’re not allowed to travel more than five miles from their homes.

Just as you begin to wonder how much pain you can take, the mood shifts.

Eddie talks with Bela Lugosi about the miseries of Tinsel Town. Hollywood only wants to cast Eddie in demeaning “Asian” parts. Lugosi complains that only one postage stamp has been made with his image. His rival Boris Karloff “has two stamps,” he says.

Mercury Pictures studio gets a momentary boost, when it, like other Hollywood studios, is called upon to make propaganda films for the War effort.

But there’s a problem when the Army brass expects Mercury’s filmmakers to film the propaganda in actual combat. “A filmmaker needs multiple takes to get the right shot” on a studio sound stage, Artie says, “The idea that you’re going to send a couple guys into a foxhole with a camera and expect to compete with Hollywood just isn’t feasible.”

“If you want the war to look real on screen, you’ll have to fake it,” he adds.

Marra, 38, isn’t faking it. “Mercury Pictures Presents” more than lives up to the promise of “The Tsar of Love and Techno” and “A Constellation of Vital Phenomena,” his earlier award-winning work. It’s a fab read.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Two new books on dining out LGBTQ-style

Visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers

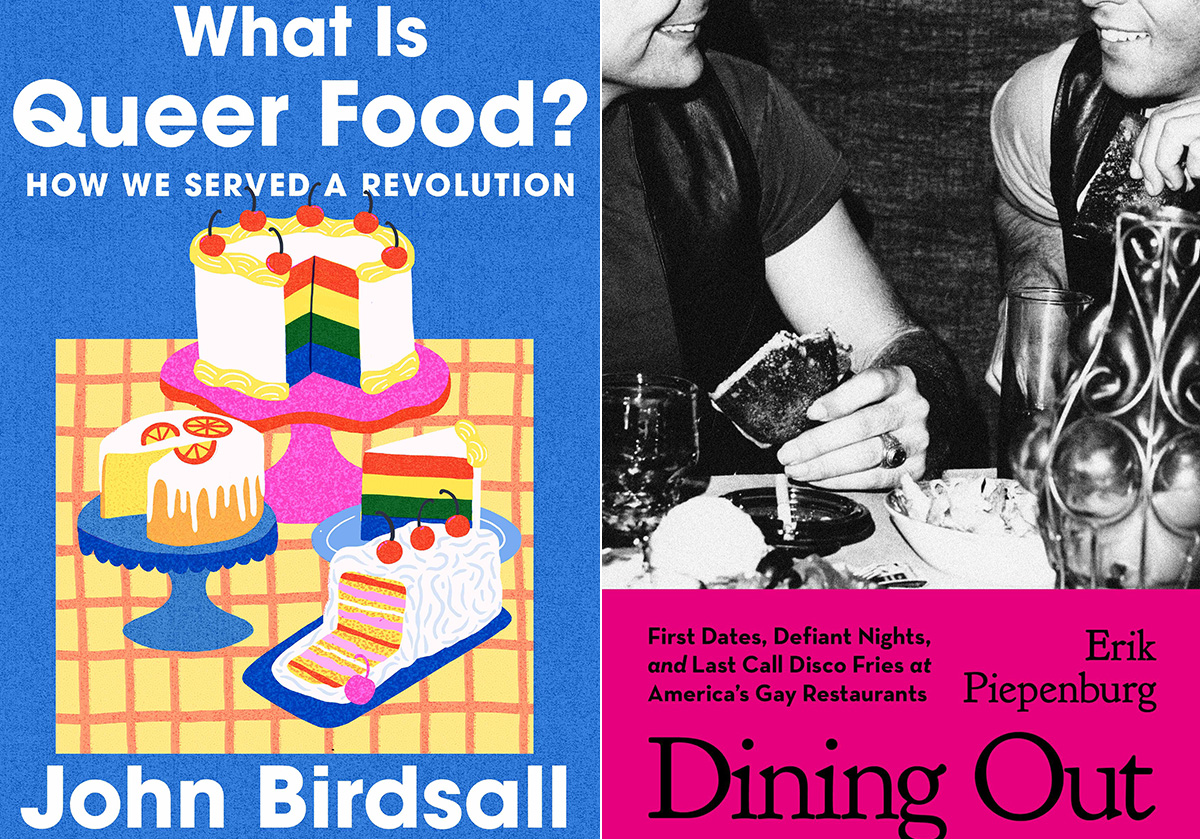

‘What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution’

By John Birdsall

c.2025, W.W. Norton

$29.99/304 pages

‘Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants’

By Erik Piepenburg

c.2025, Grand Central

$30/352 pages

You thought a long time about who sits where.

Compatibility is key for a good dinner party, so place cards were the first consideration; you have at least one left-hander on your guest list, and you figured his comfort into your seating chart. You want the conversation to flow, which is music to your ears. And you did a good job but, as you’ll see with these two great books on dining LGBTQ-style, it’s sometimes not who sits where, but whose recipes were used.

When you first pick up “What is Queer Food?” by John Birdsall, you might miss the subtitle: “How We Served a Revolution.” It’s that second part that’s important.

Starting with a basic gay and lesbian history of America, Birdsall shows how influential and (in)famous 20th century queer folk set aside the cruelty and discrimination they received, in order to live their lives. They couldn’t speak about those things, he says, but they “sat down together” and they ate.

That suggested “a queer common purpose,” says Birdsall. “This is how who we are, dahling, This is how we feed our own. This is how we stay alive.”

Readers who love to cook, bake or entertain, collect cookbooks, or use a fork will want this book. Its stories are nicely served, they’re addicting, and they may send you in search of cookbooks you didn’t know existed.

Sometimes, though, you don’t want to be stuck in the kitchen, you want someone else to bring the grub. “Dining Out” by Erik Piepenburg is an often-nostalgic, lively look at LGBTQ-friendly places to grab a meal – both now and in the past.

In his introduction, Piepenburg admits that he’s a journalist, “not a historian or an academic,” which colors this book, but not negatively. Indeed, his journeys to “gay restaurants” – even his generous and wide-ranging definitions of the term – happily influence how he presents his narrative about eateries and other establishments that have fed protesters, nourished budding romances, and offered audacious inclusion.

Here, there are modern tales of drag lunches and lesbian-friendly automats that offered “cheap food” nearly a century ago. You’ll visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers on holidays. Stepping back, you’ll read about AIDS activism at gay-friendly establishments, and mostly gay neighborhood watering holes. Go underground at a basement bar; keep tripping and meet proprietors, managers, customers and performers. Then take a peek into the future, as Piepenburg sees it.

The locales profiled in “Dining Out” may surprise you because of where they can be found; some of the hot-spots practically beg for a road trip.

After reading this book, you’ll feel welcome at any of them.

If these books don’t shed enough light on queer food, then head to your favorite bookstore or library and ask for help finding more. The booksellers and librarians there will put cookbooks and history books directly in your hands, and they’ll help you find more on the history and culture of the food you eat. Grab them and you’ll agree, they’re pretty tasty reads.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

You’re going to be on your feet a lot this month.

Marching in parades, dancing in the streets, standing up for people in your community. But you’re also likely to have some time to rest and reflect – and with these great new books, to read.

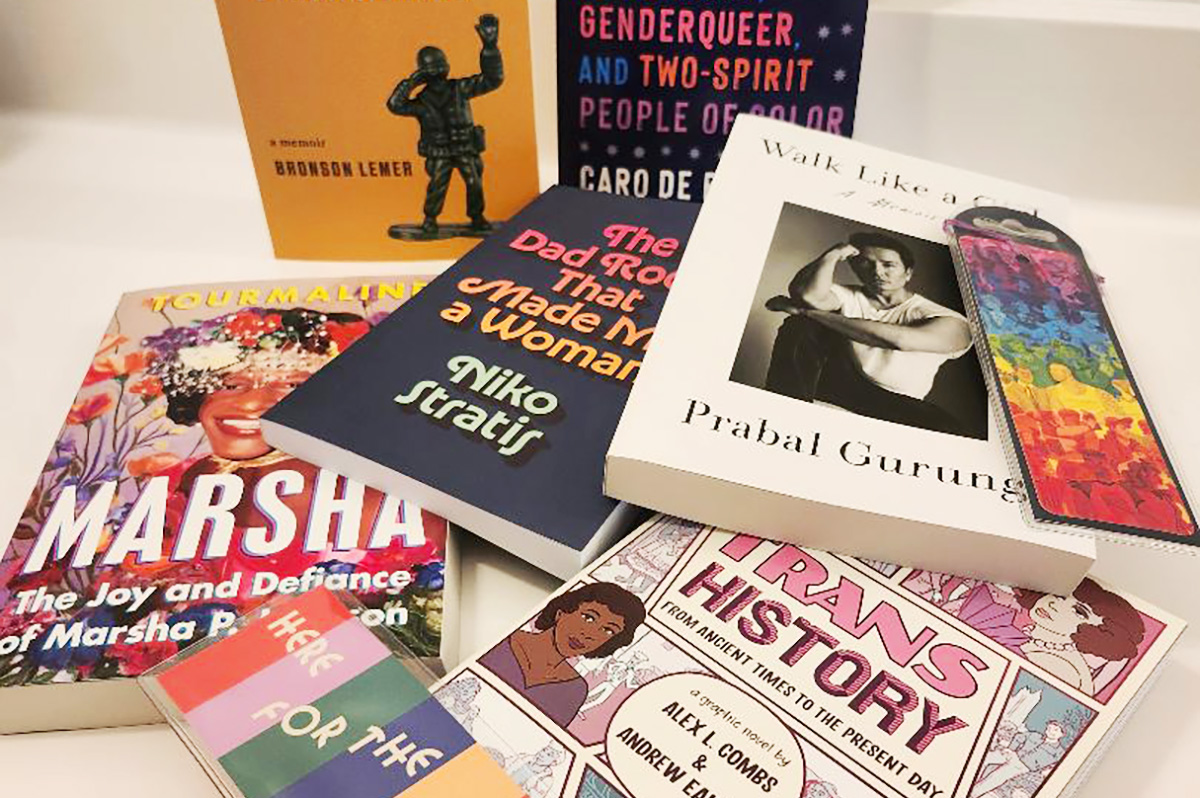

First, dip into a biography with “Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson” by Tourmaline (Tiny Rep Books, $30), a nice look at an icon who, rumor has it, threw the brick that started a revolution. It’s a lively tale about Marsha P. Johnson, her life, her activism before Stonewall and afterward. Reading this interesting and highly researched history is a great way to spend some time during Pride month.

For the reader who can’t live without music, try “The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman” by Niko Stratis (University of Texas Press, $27.95), the story of being trans, searching for your place in the world, and finding it in a certain comfortable genre of music. Also look for “The Lonely Veteran’s Guide to Companionship” by Bronson Lemer (University of Wisconsin Press, $19.95), a collection of essays that make up a memoir of this and that, of being queer, basic training, teaching overseas, influential books, and life.

If you still have room for one more memoir, try “Walk Like a Girl” by Prabal Gurung (Viking, $32.00). It’s the story of one queer boy’s childhood in India and Nepal, and the intolerance he experienced as a child, which caused him to dream of New York and the life he imagined there. As you can imagine, dreams and reality collided but nonetheless, Gurung stayed, persevered, and eventually became an award-winning fashion designer, highly sought by fashion icons and lovers of haute couture. This is an inspiring tale that you shouldn’t miss.

No Pride celebration is complete without a history book or two.

In “Trans History: From Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Alex L. Combs & Andrew Eakett ($24.99, Candlewick Press), you’ll see that being trans is something that’s as old as humanity. One nice part about this book: it’s in graphic novel form, so it’s lighter to read but still informative. Lastly, try “So Many Stars: An Oral History of Trans, Nonbinary, Genderqueer, and Two-Spirit People of Color” by Caro De Robertis (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. $32.00) a collection of thoughts, observations, and truths from over a dozen people who share their stories. As an “oral history,” you’ll be glad to know that each page is full of mini-segments you can dip into anywhere, read from cover to cover, double-back and read again. It’s that kind of book.

And if these six books aren’t enough, if they don’t quite fit what you crave now, be sure to ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for help. There are literally tens of thousands of books that are perfect for Pride month and beyond. They’ll be able to determine what you’re looking for, and they’ll put it directly in your hands. So stand up. March. And then sit and read.

a&e features

James Baldwin bio shows how much of his life is revealed in his work

‘A Love Story’ is first major book on acclaimed author’s life in 30 years

‘Baldwin: A Love Story’

By Nicholas Boggs

c.2025, FSG

$35/704 pages

“Baldwin: A Love Story” is a sympathetic biography, the first major one in 30 years, of acclaimed Black gay writer James Baldwin. Drawing on Baldwin’s fiction, essays, and letters, Nicolas Boggs, a white writer who rediscovered and co-edited a new edition of a long-lost Baldwin book, explores Baldwin’s life and work through focusing on his lovers, mentors, and inspirations.

The book begins with a quick look at Baldwin’s childhood in Harlem, and his difficult relationship with his religious, angry stepfather. Baldwin’s experience with Orilla Miller, a white teacher who encouraged the boy’s writing and took him to plays and movies, even against his father’s wishes, helped shape his life and tempered his feelings toward white people. When Baldwin later joined a church and became a child preacher, though, he felt conflicted between academic success and religious demands, even denouncing Miller at one point. In a fascinating late essay, Baldwin also described his teenage sexual relationship with a mobster, who showed him off in public.

Baldwin’s romantic life was complicated, as he preferred men who were not outwardly gay. Indeed, many would marry women and have children while also involved with Baldwin. Still, they would often remain friends and enabled Baldwin’s work. Lucien Happersberger, who met Baldwin while both were living in Paris, sent him to a Swiss village, where he wrote his first novel, “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” as well as an essay, “Stranger in the Village,” about the oddness of being the first Black person many villagers had ever seen. Baldwin met Turkish actor Engin Cezzar in New York at the Actors’ Studio; Baldwin later spent time in Istanbul with Cezzar and his wife, finishing “Another Country” and directing a controversial play about Turkish prisoners that depicted sexuality and gender.

Baldwin collaborated with French artist Yoran Cazac on a children’s book, which later vanished. Boggs writes of his excitement about coming across this book while a student at Yale and how he later interviewed Cazac and his wife while also republishing the book. Baldwin also had many tumultuous sexual relationships with young men whom he tried to mentor and shape, most of which led to drama and despair.

The book carefully examines Baldwin’s development as a writer. “Go Tell It on the Mountain” draws heavily on his early life, giving subtle signs of the main character John’s sexuality, while “Giovanni’s Room” bravely and openly shows a homosexual relationship, highly controversial at the time. “If Beale Street Could Talk” features a woman as its main character and narrator, the first time Baldwin wrote fully through a woman’s perspective. His essays feel deeply personal, even if they do not reveal everything; Lucian is the unnamed visiting friend in one who the police briefly detained along with Baldwin. He found New York too distracting to write, spending his time there with friends and family or on business. He was close friends with modernist painter Beauford Delaney, also gay, who helped Baldwin see that a Black man could thrive as an artist. Delaney would later move to France, staying near Baldwin’s home.

An epilogue has Boggs writing about encountering Baldwin’s work as one of the few white students in a majority-Black school. It helpfully reminds us that Baldwin connects to all who feel different, no matter their race, sexuality, gender, or class. A well-written, easy-flowing biography, with many excerpts from Baldwin’s writing, it shows how much of his life is revealed in his work. Let’s hope it encourages reading the work, either again or for the first time.

-

U.S. Supreme Court5 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court5 days agoSupreme Court upholds ACA rule that makes PrEP, other preventative care free

-

U.S. Supreme Court5 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court5 days agoSupreme Court rules parents must have option to opt children out of LGBTQ-specific lessons

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoWes Moore hosts annual Pride reception

-

District of Columbia5 days ago

District of Columbia5 days agoActivists protest outside Hungarian Embassy in DC