Books

Geena Davis kicked ass onscreen long before she did in real life

Iconic actress revisits her ‘Polite’ life in new memoir

‘Dying of Politeness: A Memoir’

By Geena Davis

c.2022, Harper One

$28.99/288 pages

Years ago, a colleague videotaped me as I apologized for bumping into a desk. “I’m sorry,” I said to this inanimate object, “I hope I didn’t hurt your feelings.”

If you’re terminally polite, love kick-ass movies and worship bad-asses, you’ll lap up “Dying of Politeness: A Memoir” by badass, feminist, Academy-Award-winning actor and activist Geena Davis.

In the memoir (Davis’s debut as an author), Davis, 66, tells entertaining, sometimes moving, stories about her wide-ranging life: from her childhood (her parents were more polite than Emily Post ever dreamt of) to her acting career to finishing in 24th place in archery in the 2000 Summer Olympics trials.

Davis, a queer and feminist icon, has been in many movies. Her awards include an Oscar for best supporting actress for her portrayal of dog trainer Muriel Prichett in “The Accidental Tourist,” the adaptation of the Anne Tyler novel of the same name. Davis watched her boyfriend (Jeff Goldblum) turn into an insect in “The Fly” and played Barbara in the comedy-horror picture “Beetlejuice.”

Davis is loved by LGBTQ folk for her work in two 1990s classics.

In 1991, she was Thelma (Susan Sarandon was Louise) in “Thelma and Louise,” the classic film that made many women cheer and a lot of men squirm.

Just a year later, Davis was Dottie in the movie that’s still a fave of hetero and queer girls and women — “A League of Their Own.” Unlike the series with the same name recently released by Amazon Prime, the film has no explicitly queer characters. But with Madonna (Mae) and Rosie O’Donnell (Doris), the picture has a fab queer quotient.

You’d think, after watching Davis as Thelma and Dottie, that the Oscar-winning actor leapt from her mother’s womb as a badass.

But it’s clear from the get-go that it took more than a minute for Davis to emerge as her badass self. Davis could easily have titled not only the first chapter of her memoir, but the entire book, “My Journey to Badassery.”

“I kicked ass onscreen way before I did so in real life,” Davis writes.

But, “Dying of Politeness” is a more than apt title for the memoir. Her parents were loving, but polite to the point of absurdity.

They insisted that Davis say “no thank you, I’m not thirsty” “even if someone was handing me an already poured glass of ice water,” Davis writes.

One of Davis’s childhood memories was of the time her 99-year-old great-uncle drove her and her family to his house. The relative kept veering into the oncoming “if blessedly empty,” traffic lane, she recalls. Rather than saying anything, “my parents simply moved me to the spot between them on the back seat,” Davis writes, “thinking, I presume, that when the inevitable head-on collision occurred, I’d be killed a little less in the middle.”

The humor in this anecdote of a childhood brush with death is typical of the wit sprinkled throughout “Dying of Politeness.”

Davis, who grew up in Wareham, Mass., decided at age 3 that she wanted to be in the movies. After studying acting at Boston University, Davis left college and moved to New York.

Davis may have been as she writes, “a cripplingly polite New Englander,” but she wasn’t lacking in chutzpah.

In New York, Davis worked as a Lord and Taylor sales clerk. On a dare, she joined a group of mannequins in a café scene in the department store window. Soon, people lined up to watch her perform in street theater.

Davis got her first movie role in “Tootsie” after Sidney Pollack saw her pictures in the Victoria’s Secret catalogue. Dustin Hoffman, starring in the movie, mentored her. He told her not to sleep with her co-stars.

The memoir is more than entertaining. Davis writes of sexual harassment, her effort to create inclusion in Hollywood by founding the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media and how her dad cared for her mom when she had dementia.

It’s hard to think of a timelier book than “Dying of Politeness” in our current political climate. Badassery is needed now more than ever.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

You’re going to be on your feet a lot this month.

Marching in parades, dancing in the streets, standing up for people in your community. But you’re also likely to have some time to rest and reflect – and with these great new books, to read.

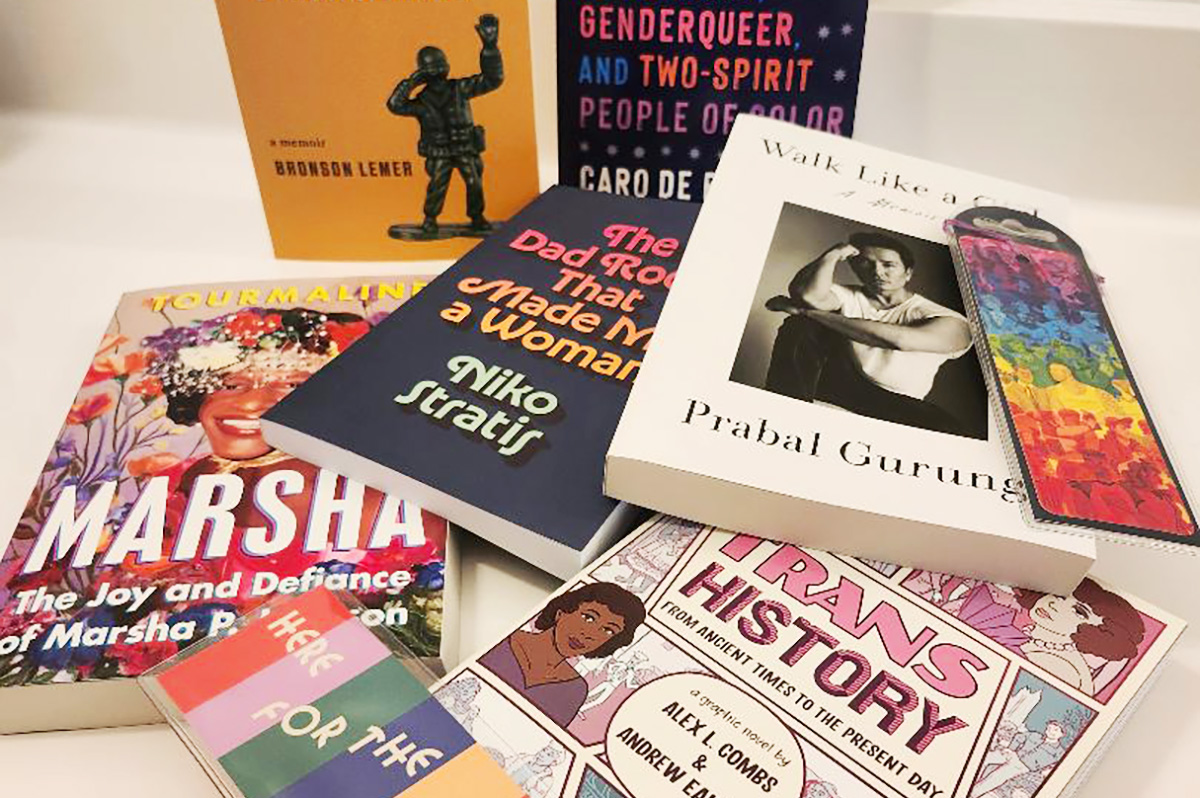

First, dip into a biography with “Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson” by Tourmaline (Tiny Rep Books, $30), a nice look at an icon who, rumor has it, threw the brick that started a revolution. It’s a lively tale about Marsha P. Johnson, her life, her activism before Stonewall and afterward. Reading this interesting and highly researched history is a great way to spend some time during Pride month.

For the reader who can’t live without music, try “The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman” by Niko Stratis (University of Texas Press, $27.95), the story of being trans, searching for your place in the world, and finding it in a certain comfortable genre of music. Also look for “The Lonely Veteran’s Guide to Companionship” by Bronson Lemer (University of Wisconsin Press, $19.95), a collection of essays that make up a memoir of this and that, of being queer, basic training, teaching overseas, influential books, and life.

If you still have room for one more memoir, try “Walk Like a Girl” by Prabal Gurung (Viking, $32.00). It’s the story of one queer boy’s childhood in India and Nepal, and the intolerance he experienced as a child, which caused him to dream of New York and the life he imagined there. As you can imagine, dreams and reality collided but nonetheless, Gurung stayed, persevered, and eventually became an award-winning fashion designer, highly sought by fashion icons and lovers of haute couture. This is an inspiring tale that you shouldn’t miss.

No Pride celebration is complete without a history book or two.

In “Trans History: From Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Alex L. Combs & Andrew Eakett ($24.99, Candlewick Press), you’ll see that being trans is something that’s as old as humanity. One nice part about this book: it’s in graphic novel form, so it’s lighter to read but still informative. Lastly, try “So Many Stars: An Oral History of Trans, Nonbinary, Genderqueer, and Two-Spirit People of Color” by Caro De Robertis (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. $32.00) a collection of thoughts, observations, and truths from over a dozen people who share their stories. As an “oral history,” you’ll be glad to know that each page is full of mini-segments you can dip into anywhere, read from cover to cover, double-back and read again. It’s that kind of book.

And if these six books aren’t enough, if they don’t quite fit what you crave now, be sure to ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for help. There are literally tens of thousands of books that are perfect for Pride month and beyond. They’ll be able to determine what you’re looking for, and they’ll put it directly in your hands. So stand up. March. And then sit and read.

a&e features

James Baldwin bio shows how much of his life is revealed in his work

‘A Love Story’ is first major book on acclaimed author’s life in 30 years

‘Baldwin: A Love Story’

By Nicholas Boggs

c.2025, FSG

$35/704 pages

“Baldwin: A Love Story” is a sympathetic biography, the first major one in 30 years, of acclaimed Black gay writer James Baldwin. Drawing on Baldwin’s fiction, essays, and letters, Nicolas Boggs, a white writer who rediscovered and co-edited a new edition of a long-lost Baldwin book, explores Baldwin’s life and work through focusing on his lovers, mentors, and inspirations.

The book begins with a quick look at Baldwin’s childhood in Harlem, and his difficult relationship with his religious, angry stepfather. Baldwin’s experience with Orilla Miller, a white teacher who encouraged the boy’s writing and took him to plays and movies, even against his father’s wishes, helped shape his life and tempered his feelings toward white people. When Baldwin later joined a church and became a child preacher, though, he felt conflicted between academic success and religious demands, even denouncing Miller at one point. In a fascinating late essay, Baldwin also described his teenage sexual relationship with a mobster, who showed him off in public.

Baldwin’s romantic life was complicated, as he preferred men who were not outwardly gay. Indeed, many would marry women and have children while also involved with Baldwin. Still, they would often remain friends and enabled Baldwin’s work. Lucien Happersberger, who met Baldwin while both were living in Paris, sent him to a Swiss village, where he wrote his first novel, “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” as well as an essay, “Stranger in the Village,” about the oddness of being the first Black person many villagers had ever seen. Baldwin met Turkish actor Engin Cezzar in New York at the Actors’ Studio; Baldwin later spent time in Istanbul with Cezzar and his wife, finishing “Another Country” and directing a controversial play about Turkish prisoners that depicted sexuality and gender.

Baldwin collaborated with French artist Yoran Cazac on a children’s book, which later vanished. Boggs writes of his excitement about coming across this book while a student at Yale and how he later interviewed Cazac and his wife while also republishing the book. Baldwin also had many tumultuous sexual relationships with young men whom he tried to mentor and shape, most of which led to drama and despair.

The book carefully examines Baldwin’s development as a writer. “Go Tell It on the Mountain” draws heavily on his early life, giving subtle signs of the main character John’s sexuality, while “Giovanni’s Room” bravely and openly shows a homosexual relationship, highly controversial at the time. “If Beale Street Could Talk” features a woman as its main character and narrator, the first time Baldwin wrote fully through a woman’s perspective. His essays feel deeply personal, even if they do not reveal everything; Lucian is the unnamed visiting friend in one who the police briefly detained along with Baldwin. He found New York too distracting to write, spending his time there with friends and family or on business. He was close friends with modernist painter Beauford Delaney, also gay, who helped Baldwin see that a Black man could thrive as an artist. Delaney would later move to France, staying near Baldwin’s home.

An epilogue has Boggs writing about encountering Baldwin’s work as one of the few white students in a majority-Black school. It helpfully reminds us that Baldwin connects to all who feel different, no matter their race, sexuality, gender, or class. A well-written, easy-flowing biography, with many excerpts from Baldwin’s writing, it shows how much of his life is revealed in his work. Let’s hope it encourages reading the work, either again or for the first time.

You’ve done your share of marching.

You’re determined to wring every rainbow-hued thing out of this month. The last of the parties hasn’t arrived yet, neither have the biggest celebrations and you’re primed but – OK, you need a minute. So pull up a chair, take a deep breath, and read these great books on gay history, movies, and more.

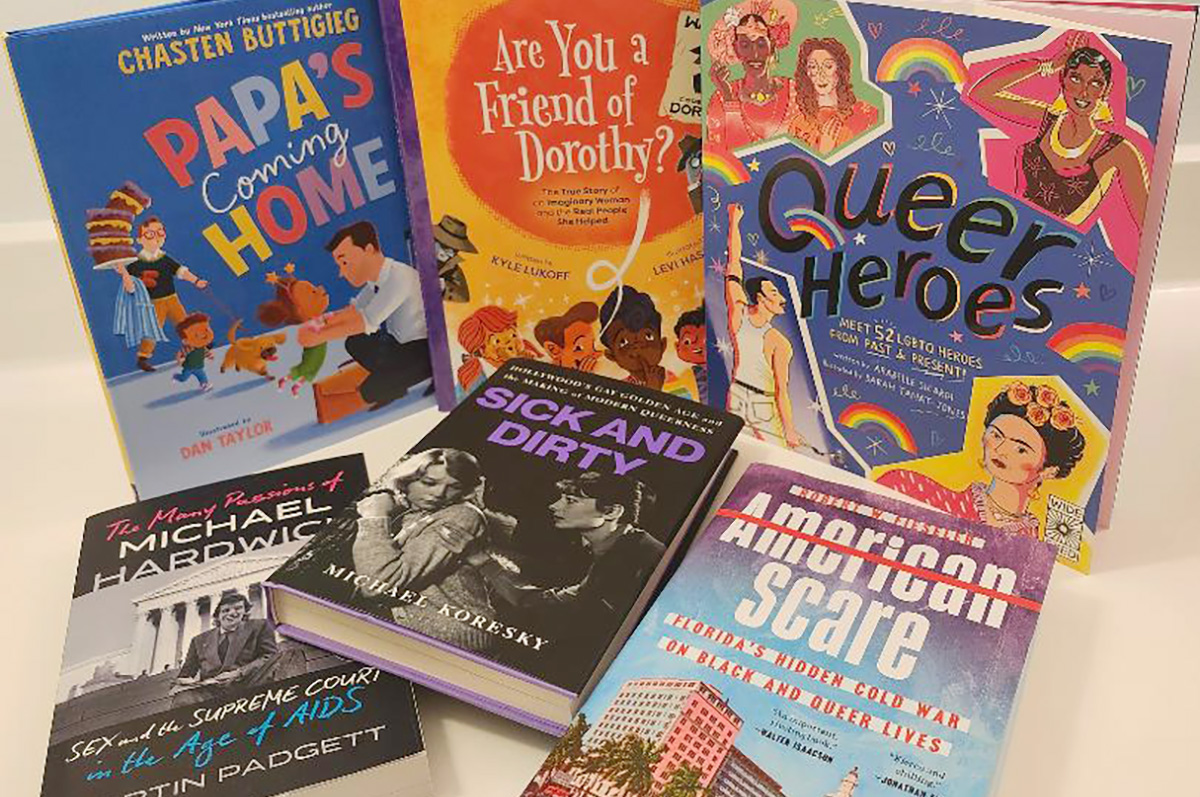

You probably don’t need to be told that harassment and discrimination was a daily occurrence for gay people in the past (as now!), but “American Scare: Florida’s Hidden Cold War on Black and Queer Lives” by Robert W. Fieseler (Dutton, $34) tells a story that runs deeper than you may know. Here, you’ll read a historical expose with documented, newly released evidence of a systemic effort to ruin the lives of two groups of people that were perceived as a threat to a legislature full of white men.

Prepared to be shocked, that’s all you need to know.

You’ll also want to read the story inside “The Many Passions of Michael Hardwick: Sex and the Supreme Court in the Age of AIDS” by Martin Padgett (W.W. Norton & Company, $31.99), which sounds like a novel, but it’s not. It’s the story of one man’s fight for a basic right as the AIDS crisis swirls in and out of American gay life and law. Hint: this book isn’t just old history, and it’s not just for gay men.

Maybe you’re ready for some fun and who doesn’t like a movie? You know you do, so you’ll want “Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness” by Michael Koresky (Bloomsbury, $29.99). It’s a great look at the Hays Code and what it allowed audiences to see, but it’s also about the classics that sneaked beneath the code. There are actors, of course, in here, but also directors, writers, and other Hollywood characters you may recognize. Grab the popcorn and settle in.

If you have kids in your life, they’ll want to know more about Pride and you’ll want to look for “Pride: Celebrations & Festivals” by Eric Huang, illustrated by Amy Phelps (Quarto, $14.99), a story of inclusion that ends in a nice fat section of history and explanation, great for kids ages seven-to-fourteen. Also find “Are You a Friend of Dorothy? The True Story of an Imaginary Woman and the Real People She Helped Shape” by Kyle Lukoff, illustrated by Levi Hastings (Simon & Schuster, $19.99), a lively book about a not-often-told secret for kids ages six-to-ten; and “Papa’s Coming Home” by Chasten Buttigieg, illustrated by Dan Taylor (Philomel, $19.99), a sweet family tale for kids ages three-to-five.

Finally, here’s a tween book that you can enjoy, too: “Queer Heroes” by Arabelle Sicardi, illustrated by Sarah Tanat-Jones (Wide Eyed, $14.99), a series of quick-to-read biographies of people you should know about.

Want more Pride books? Then ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for more, because there are so many more things to read. Really, the possibilities are almost endless, so march on in.