Opinions

LGBTQ elder voices matter now more than ever

Global Story Archive highlights often ignored perspectives

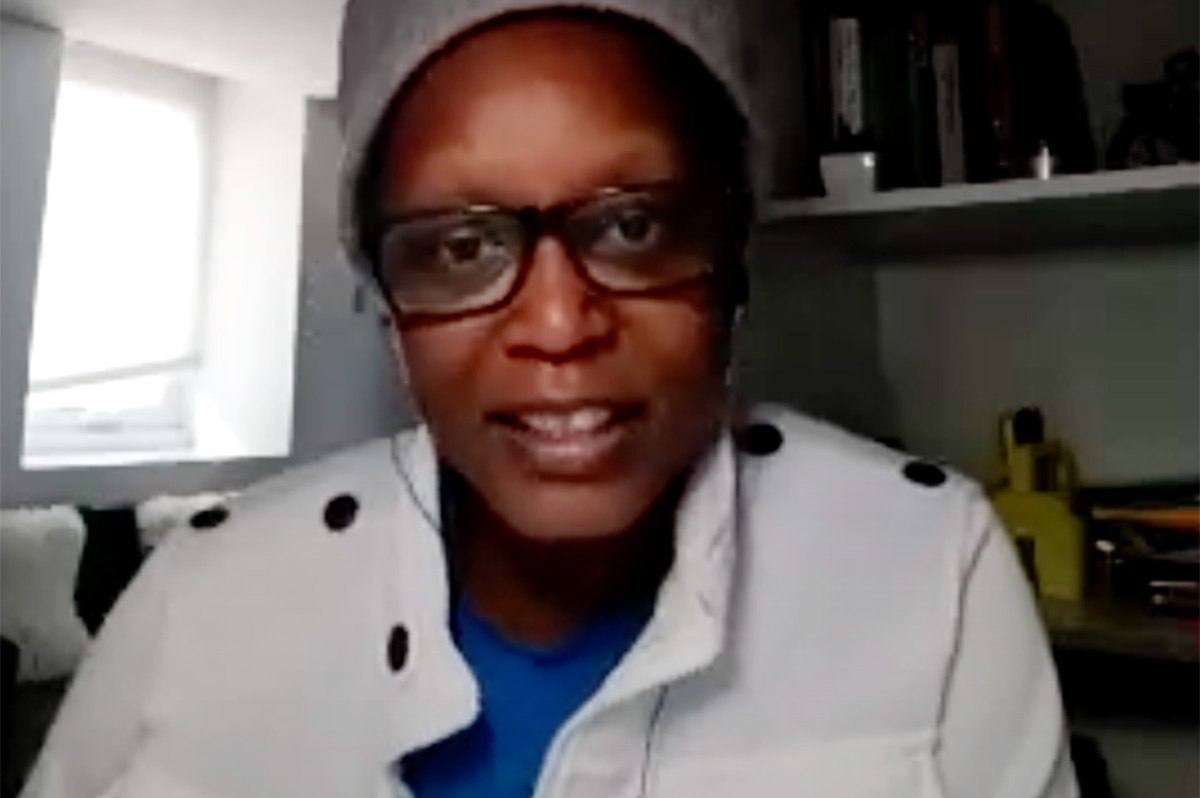

Kasha Nabagesera is widely regarded as the Mother of the Ugandan LGBTQ+ human rights movement. As one of the most prominent human rights activists of our time, she is no stranger to speaking publicly about her life. However, when I had the privilege of sitting down with her this February, she opened up about a part of her story that is often overlooked—or, even worse, ridiculed. Aging.

When Kasha turned 40, she began to notice a shift in how people viewed and spoke about her lived experience. In the years since, she has received hurtful and dismissive messages from younger LGBTQ+ people who believe her age renders her opinions and perspective irrelevant. These individuals fail to recognize that the sacrifices made by Kasha and other elders have paved the way for today’s young queer people to live their lives openly and proudly.

Disregard for LGBTQ+ elders is not just disrespectful—it’s a missed opportunity for connection at a time when solidarity among LGBTQ+ people is desperately needed. The number of anti-LGBTQ+ bills continues to rise in state legislatures across the U.S., and about one-third of the world’s countries, including 60 UN member states, still criminalize consensual same-sex sexual acts.

The reality is that our elders are true pioneers of the LGBTQ+ movement worldwide. They have survived decades of discrimination and state-sanctioned violence, leading them to face many unique challenges.

Many report having to “go back into the closet” to access care in later years, lack family support networks, and discrimination in housing and healthcare. LGBTQ+ older adults are also less likely to have retirement savings due to decades of employment discrimination.

Through these struggles, LGBTQ+ elders have developed remarkable wisdom, and their lived experiences can provide a roadmap for resilience in the face of new obstacles. But too often, we fail to listen to them, and their contributors are forgotten.

Over the last three and a half years as director of International Programs at SAGE, I have spoken with hundreds of elders worldwide about their lives and legacies. Most have shared similar experiences of ageism and a desire to pass on their knowledge to younger generations.

One of those elders is Reingard Wagnar, a 74-year-old lesbian and activist from Germany. She said that not only are older women in society rendered invisible anyway, but it is especially true for older lesbians. She wants people to know that elder LGBTQ+ folks are here, and they have much to share.

Another elder I had the honor of meeting, Kevin Mchawiro, is a Kenyan journalist and believes stories can also serve as a source of inspiration and that love does indeed win.

To collect, preserve, share and amplify the stories of elders like Kasha, Reingard, and Kevin, I created The Global Story Archive. Supported by SAGE and in collaboration with a global network of not-for-profit organizations and independent activists, this first-of-its-kind collection features the voices of dozens of LGBTQ+ elders who are eager to share their perspectives across generations and borders.

However, in the wake of Trump’s Executive Orders on Foreign Aid, the uncertainty of where funding and support lies, and what the future looks like, SAGE must close its global operations. This suspension is happening in tandem with the dismantling of foreign aid programs that advance the well-being of other underserved populations, including immigrants, women, and those burdened by disease.

The loss extends beyond funding cuts or policy shifts; it represents the erosion of programs that have fostered solidarity and advanced the well-being of us all.

If you find yourself asking how to find resilience in this turmoil, the answer is simple: look to our elders. Our international community of LGBTQ+ elders has lived through and witnessed moments of upheaval, tragedy, and triumph, and they hold priceless knowledge to counsel younger generations through hardship.

The state of the world is uncertain, but as elders will tell you, it can get better.

To hear and learn from the voices of our global community of LGBTQ+ elders, please visit The Global Story Archive.

Hannah Yore is an international health and human rights advocate with expertise in aging, care work, and LGBTIQ human rights. She is the former director of International Programs at SAGE and is a dedicated palliative care and end-of-life doula.

Opinions

Criteria for supporting a candidate in D.C.

We deserve statehood and mayoral control of our National Guard

Choosing a candidate to support for office in D.C. is a little different than choosing one in other places. As everyone knows, D.C. isn’t a state; though apparently not everyone understands what that means.

D.C. was granted home rule in 1974, but the legislation gave us only partial control of our government. Congress retained the right to review all legislation and budgets for 30 days. During that time, it can reject legislation fully or just make changes. Recently, Congress has used that power to turn down legislation when the Council revised our criminal code and screwed with legislation regarding how we tax our own residents. Congress has messed with our budgets as well. We saw what happened when the felon in the White House took control of the MPD for 30 days, allowed under the home rule legislation, and how he has full control over the D.C. National Guard and the implications that has had.

We have no representation in Congress, just a delegate. That person has been given a vote in committees when Democrats controlled the House, but even then, no vote in the full House. That all has severe implications for our elected officials. They must be aware of these things when they speak out, and when they propose and pass legislation. I personally saw that close up when we fought for marriage equality in the District. Those of us leading the charge worked with the Council on legislation to first recognize gay marriages from other states. Only after that legislation went through the review period without being stopped did the Council move to pass marriage equality in the District. Then we held our breath for the 30-day review period. There have been other instances where Congress stopped crucial legislation and put amendments onto our bills, like stopping us from spending certain money on needle exchange during the height of the AIDS crisis and stopping us from spending federal money on abortions.

So, when deciding who to support I want to be sure a candidate understands the implications if they attack Congress and the president, especially when Republicans are in charge. The fact is we have been screwed even by some Democrats. In today’s world, until we get rid of the felon, and Democrats take back both houses of Congress, all of our elected officials, but particularly our mayor, will be walking a tightrope. Beating your chest and attacking what they are doing is not the way to go. Again, we are not in the same position as cities like Portland, Minneapolis, or LA. We saw that again when the courts said the National Guard had to leave those cities, the president couldn’t send them in, but D.C. was exempt from that decision because he can send them here. The president, not the mayor, controls the National Guard in D.C.

Once I am comfortable a candidate understands all that, my criteria for supporting them of course includes many other things. I am a liberal, born in New York City. I taught public school in Harlem and was a member of the teacher’s union. Then went to work for progressive Congresswoman Bella S. Abzug (D-N.Y.). After that, I served as Coordinator of Local Government for the City of New York, during the time of the financial control board there. Then came to D.C. in 1978 to work for the Carter administration. I have been an activist all my life in the areas of civil rights, women’s rights, disability rights, and finally LGBTQ rights. I am a community and Democratic activist. All this impacts my decisions regarding candidates. I want to hear consistency from them. I don’t have a problem with people changing their mind on issues based on principle but do have a problem when it seems like they do so based on which way the wind is blowing. Like those who screamed ‘Defund the Police’ until the community they thought wanted to hear that in D.C. actually told them they wanted more police, not less. They simply wanted them better trained, held more accountable, and more community oriented.

I want a candidate to support statehood for D.C., but while fighting for that, they should speak out for budget and legislative autonomy. They must support mayoral control of the DC National Guard, and a full 4,000 member, well trained, MPD. They must understand how MPD works with federal law enforcement like the FBI, park police, capitol police, and the secret service. They need to reject working with ICE. They need to support more affordable housing, but not city owned housing, which has proven to be a failed experiment. They need to pledge to work to end homelessness providing decent, and available, shelters around the city for both individuals, and families in need. I want a strong education Mayor who supports teachers, and works to expand accountability for charter schools, holding them to the same standards as the public schools. We must have strong programs for both college bound students, and those who want another path, including internships and apprenticeships. Strong support for UDC, healthcare both affordable and available for all, and rental and food assistance when needed. There needs to be a strong focus on reducing the cost of childcare. A focus on the ARTS, libraries, and recreation centers, across all wards of the city. A focus on the environment, and affordable and accessible transportation. Of course, for me it’s a given they must support, and speak out, for the full panoply of rights for the LGBTQ community.

Looking at that list clearly means the city needs to raise the money to pay for all of it. Any candidate running for office who says they don’t support a strong, and vibrant, business sector, is either naïve, or just dumb, and will not have my support. A vibrant business community provides jobs, and in the long run the taxes that pay for the things we all want government to provide.

Once again D.C. is in a different place. We don’t collect taxes from those who work here but live in Maryland or Virginia. So, we have to be smart about the businesses we encourage to locate here and encourage them to hire D.C. residents, who then will pay taxes here. D.C. has developed a strong sports economy. That will be enhanced by the new RFK site, and includes the teams at the Capital Center, Audi Field, and Nats Stadium. Together they bring millions of people into D.C., who spend their money here. When groups like the Working Families Party, who suggest they are anti-business, endorse a candidate, I am wary of that candidate. We can’t be anti-business in D.C. I look at some candidates trying to replicate Mamdani’s victory in New York City by promising the moon. What they don’t seem to realize, or pretend not to, but voters must understand, is we in D.C., our Council and mayor, can’t promise what a New York City mayor does, hoping the governor and Albany, will help him out. In D.C. we don’t have an Albany to help us out. There is no governor coming to the rescue, it’s just us, and what we can negotiate with our Albany, which unfortunately consists of the president and Congress. Some may remember in 1995 we had the Control Board foisted on us. It was lucky at the time the president was a Democrat, Bill Clinton, and he named the board and chair, first Andrew Brimmer, and then the incredible Alice Rivlin. Can you imagine if Congress did that today who Trump would name to control our city?

So, we can’t only dump on them, and attack them, at least the mayor can’t, as she/he/they have to often ask them for help, and stave off their gratuitous attacks. As a columnist, and private citizen, I can attack the felon and his Republican sycophants in Congress all I want, I do and will continue to do so. But those we elect need to understand some constraint. The need to understand sometimes they are walking that tightrope when dealing with the White House and Congress.

I urge everyone to look closely at all the candidates, and then when you decide who you want, make sure you VOTE!

Peter Rosenstein is a longtime LGBTQ rights and Democratic Party activist.

Opinions

The global cost of Trump’s foreign aid ideology

Expanded global gag rule polices people’s identity

U.S. Vice President JD Vance on Jan. 23 announced the new Promoting Human Flourishing in Foreign Assistance Policy. This policy, which has nothing to do with flourishing, is part of the Trump administration’s effort to weaponize U.S. foreign assistance to enforce ideological conformity, to police people’s identity, and to suppress dissent — both at home and abroad.

One of the policy’s three pillars advances a discriminatory framework that denies transgender people’s existence and seeks to censor organizations that affirm transgender people and their rights.

The new policy expands the Mexico City Policy, also known as the global gag rule, which has restricted U.S. foreign aid to non-U.S. civil society organizations providing abortion care under every Republican administration since 1984. What is new — and unprecedented — is the expansion of this rights-restricting logic to efforts addressing gender identity and, more broadly, nondiscrimination efforts.

The new policy also applies to more categories of aid recipients, including multilateral organizations such as UN agencies.

With the expanded global gag rule, the Trump administration seeks to make transgender people invisible globally, as it has within the U.S. Whether it is threatening steep tariffs for countries that resist Trump’s appetite for Greenland, or withholding funds for organizations that refuse to toe the ideological line, the chilling message is clear: standing in the way of the administration’s political or ideological goals will come at a high cost.

Under this rule, organizations risk losing U.S. funding if their activities are seen to fall under the spurious concept of “gender ideology.” Organizations are not allowed to provide, refer for, or support access to gender-affirming care. Neither can they offer accurate information, counseling, or public-facing support for transgender people. The restrictions even apply to cultural activities such as “drag queen workshops, performances, or documentaries.”

Organizations that receive any foreign aid from the U.S. will need to censor themselves, even if their own national or regional laws enable — or oblige — them to speak up for human rights.

This new policy comes after the Trump administration dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development, which has for decades provided the bulk of U.S. international development and humanitarian assistance.

To be clear, LGBT people, regardless of where they are, do not depend on the United States to organize, advocate, and stand up for their rights. And foreign aid is not the answer to undoing global inequity. But the sharp reversal of U.S. foreign policy will have wide-ranging consequences.

For years, protecting the rights of LGBT people had been a core tenet of the U.S. commitment to human rights. U.S. embassies often functioned as safe havens for human rights defenders in places where governments stoked homo- and transphobia for political gain. For LGBT people in the 65 countries that still criminalize same-sex intimacy, civil society-run clinics, supported with U.S. funds, became life-saving spaces — people could get HIV and other care there without fear of being turned away, ridiculed, or reported to the police.

Much of this is progress is now at risk. As a result of the U.S. funding cuts, organizations that directly provided health care and other services for LGBT people were forced to stop services abruptly, cutting off people’s access to chronic medication often without alternative care in place.

The impact extends beyond individual harm. Public health programs by definition are more likely to fail when stigma and fear are institutionalized. Transgender people are among the groups most at risk for ill health precisely because of discrimination and violence.

By prohibiting organizations, from local civil society groups to multilateral organizations like UNAIDS, from affirming transgender identities or addressing these underlying conditions, the expanded global gag rule actively undermines the foundations of effective public health programs.

Under the new and expanded gag rule, organizations face a terrible choice for accepting any U.S. funding. They can either self-censor and stop all work related to transgender people’s rights and needs. Or they forego U.S. funds and risk jeopardizing their organizational survival in an increasingly tough economic and funding climate.

This matters because civil society is one of the few effective counterweights to the global rise of populist and authoritarian governance. Alongside a coordinated global backlash against women’s and LGBT people’s rights are efforts to concentrate power, erode accountability, and close civic space.

Civil society organizations are crucial in exposing and resisting the authoritarian creep and in supporting marginalized groups. Gagging organizations into silence, or hollowing them out through funding cuts, accelerates civic space closure, and strengthens authoritarian governance.

Where the U.S. retreats and bullies, other countries and communities need to step up to offset the funding shortfalls and reduce organizations’ dependency on ideologically restricted U.S. foreign aid.

They need to support marginalized groups, increase funding for civil society groups, and commit funds to bolster multilateral mechanisms such as the Global Fund, which supports funding to combat HIV/AIDS, TB, and Malaria. They should clearly and consistently affirm everyone’s human rights, without exception.

Alex Muller is the director of Human Rights Watch’s LGBT Rights Program.

..

Renee Good. Alex Pretti.

During this last year, I wondered who would be the first U.S. citizen to be shot by our government. It was not a matter of if, but when. Always.

And now we know.

I thought it would be soldiers. But the masked men got there first. Because when you mix guns and protests, guns inevitably go off. The powers that be always knew it, hoped for it, and wanted it to happen.

Why? Because masked men and guns instill fear. And that’s the point. Ask yourself when’s the last time you saw masked men and guns in our cities, or anywhere for that matter. I always thought that men masked men with guns robbed banks. I was wrong.

Masked men want to rob us of our dignity as human beings. Of our assurance in the calmness and contentment of our communities. They want to rob us of our trust in our institutions, and our faith in each other. And truly they want to rob us of the happiness and joy that we all constantly yearn to find in our lives.

But our only collective ability as a nation to push back is our protests. Peaceful protests. As Renee and Alex did.

But peaceful protests? Because they are the perfect power to shame the cowardice of those that believe guns and force are the only true authority. Fortunately, our last hope and fiercest ally is our Constitution, which gives us the power — and the right — to protest.

How much more peaceful can you get when you hear Renee Good’s last words, “I’m not mad at you, Dude.” I may be mad at the system, the government, the powers of unknown people pulling the strings but not you personally. “Dude.” Peaceful to the last word.

Yet, what becomes lost in the frantic pace of hair-trigger news cycles, of officials declaring impetuous damnations alongside johnny-on-the spot podcasters spouting their split-second opinions are the two human beings who have lost their lives.

How habituated we’ve become as we instantly devour their instant obituaries. The sum of their lives declared in less than 10 seconds of cellphone video. They haven’t just lost their lives. They’ve lost all of their lives. And now we watch over and over again as their death is re-revealed, re-churned, re-evaluated, and re-consumed. In that endless repetition, we forget the meaning of life itself.

We must remember that Renee and Alex believed in their communities, in the purpose of their work, in the happiness of their loves and lives, and in the dignity and curiosity of life itself. They were singular individuals who did not deserve to die at the end of a gun barrel for any reason, ever.

How fitting that Renee was a poet. Sometimes in confronting the massiveness of loss in our lives, we look to our poetry and our psalms, our hymns and our lullabies, to find a moment of solace in our communal grief, and to remember Renee and Alex, for what they gave us in life.

Yet, at this moment, I cannot escape the reality of what was taken from them so soon, so violently and so forever. They were exceptionally courageous and normal people, and for that reason, I must remember them through a poem to explain to me, and others, the unexplainable.

I dream of this not happening.

I dream this day and night.

For none of this is real.

And none of this is right.

I dream of these sons and daughters

who now will not go home,

and dream of their mothers and fathers,

who now must stand alone.

I dream of all the flowers that they will never hold —

the kisses never shared again, the secrets to not be told.

I dream of all the sunsets that for them will never set,

I dream of all the love they gave and now they must forget.

I dream of all their dinners

with wine to never spill,

or books to read, or bread to break

or babies to be held.

I dream of each one still reaching

in the middle of the night,

for a hand that needs another

to stop a nightmare’s flight.

I dream of them not dreaming,

which I could never do,

for how can you not dream a dream

that never will come true.

I dream of this not happening.

I dream this day and night.

For none of this is real

And none of this is right.

Carew Papritz is the award-winning author of “The Legacy Letters,” who inspires kids to read through his “I Love to Read” and the “First-Ever Book Signing” YouTube series.

-

Mexico4 days ago

Mexico4 days agoUS Embassy in Mexico issues shelter in place order for Puerto Vallarta

-

Real Estate4 days ago

Real Estate4 days ago2026: prices, pace, and winter weather

-

Theater4 days ago

Theater4 days agoJosé Zayas brings ‘The House of Bernarda Alba’ to GALA Hispanic Theatre

-

Netherlands4 days ago

Netherlands4 days agoRob Jetten becomes first gay Dutch prime minister