a&e features

Newsom pardons LGBTQ and Black icon Rustin, stained by ‘historic homophobia’

‘Laws have been used as legal tools of oppression’

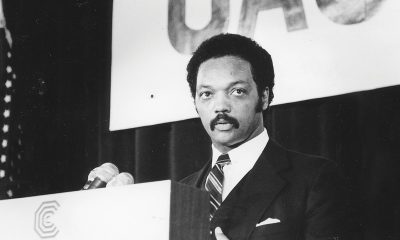

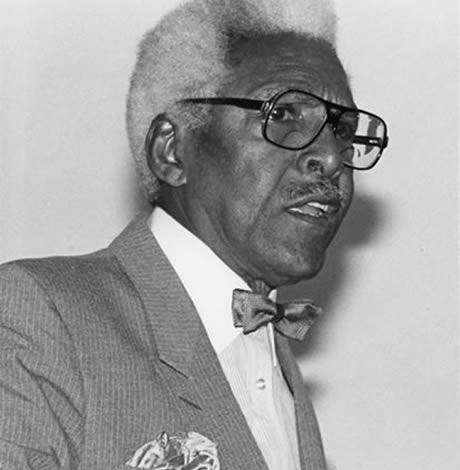

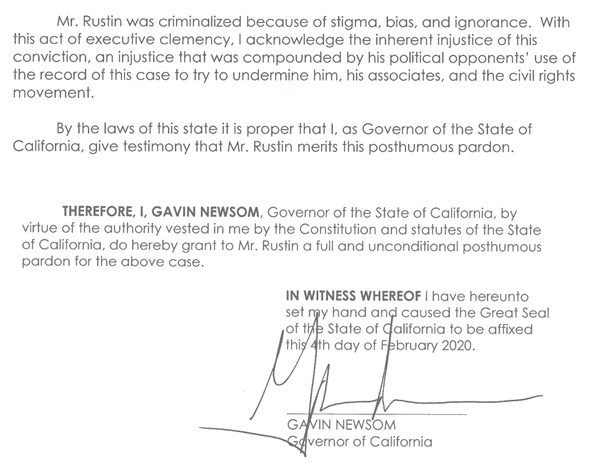

It was a patch of blue in the dark storm stalled over the divided states of America. On Feb. 5, California Gov. Gavin Newsom parted the pall and pardoned Bayard Rustin, mentor to Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington. Though President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Rustin the Medal of Freedom in 2013, the gay civil rights icon still had the stain of a 1953 “morals charge” arrest in Pasadena on his lifetime of achievement.

“In California and across the country, many laws have been used as legal tools of oppression, and to stigmatize and punish LGBTQ people and communities and warn others what harm could await them for living authentically,” Newsom said in a statement. “I thank those who advocated for Bayard Rustin’s pardon, and I want to encourage others in similar situations to seek a pardon to right this egregious wrong.”

Excerpt of the pardon certificate

Rustin’s pardon launches a new clemency initiative for people who were prosecuted in California for being gay. In 1970, after the Stonewall riots and the movement for Gay Liberation, Assemblymember Willie Brown introduced the Consenting Adult Sex Bill to repeal the sodomy law and decriminalize gay sex. Five years later, with help from San Francisco Mayor George Moscone, the bill was finally passed and signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown on May 12, 1975. But those convicted of engaging in consensual adult sexual conduct remained on the Sex Offender Registry until 1997, when a new law established a process enabling individuals to request removal. However, the original criminal conviction remained.

Newsom’s announcement acknowledges the systemic persecution of LGBTQ people and offers legal reparation.

“In California and across the country, charges like vagrancy, loitering, and sodomy have been used to unjustly target [LGBTQ] people. Law enforcement and prosecutors specifically targeted LGBTQ individuals, communities and community spaces for criminal prosecution. Now, as a proudly LGBTQ-allied state, California is turning the page on historic wrongs,” says the press release.

“There’s a cloud hanging over him because of this unfair, discriminatory conviction, a conviction that never should have happened, a conviction that happened only because he was a gay man,” state Sen. Scott Wiener, chair of California’s legislative LGBTQ caucus said Jan. 21 at a news conference with Assemblymember Shirley Weber, chair of the state’s Legislative Black Caucus, formally asking for a pardon.

“I’m thrilled that Governor Newsom is pardoning Bayard Rustin and that he acted so quickly and decisively in response to our request. I also applaud the Governor for broadening this work to provide other criminalized LGBT people with a path to clear their records of wrongful convictions on homophobic charges. These actions are consistent with the Governor’s deep and longstanding support for the LGBT community,” Wiener said in a statement. “Generations of LGBT people – including countless gay men – were branded criminals and sex offenders simply because they had consensual sex. This was often life-ruining, and many languished on the sex offender registry for decades. The Governor’s actions today are a huge step forward in our community’s ongoing quest for full acceptance and justice.”

“On behalf of the Black Caucus, I want to thank the Governor for granting this posthumous pardon. The Arc of Justice is long, but it took nearly 70 years for Bayard Rustin to have his legacy in the Civil Rights movement uncompromised by this incident. Rustin was a great American who was both gay and black at a time when the sheer fact of being either or both could land you in jail,” said Weber. “This pardon assures his place in history and the Governor’s ongoing commitment to addressing similar convictions shows that California is finally addressing a great injustice.”

“Civil rights champion Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, ‘The time is always right to do what is right.’ For our friend Governor Newsom, that time is today. We are grateful to the governor for demonstrating our California values by pardoning civil rights hero, Bayard Rustin — a trusted aide to Dr. King — and for creating a system for other LGBTQ+ people to seek pardon from unjust convictions, said Equality California Executive Director Rick Zbur. “Today, Governor Newsom, and indeed the entire Golden State, did the right thing.”

That the pardon comes at the beginning of Black History Month is notable. On the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington, Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. wrote on The Root: “I ask that if you teach your children one new name from the heroes of black history, please let it be Bayard Rustin.”

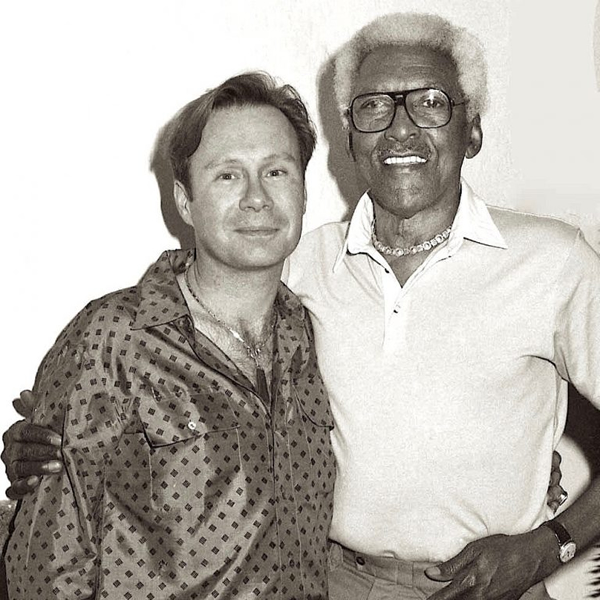

“For decades, this great leader, often at Dr. King’s side, was denied his rightful place in history because he was openly gay,” said President Obama, presenting Rustin’s medal to his longtime partner, Walter Naegle on Aug. 8, 2013. “No medal can change that, but today, we honor Bayard Rustin’s memory by taking our place in his march towards true equality, no matter who we are or who we love.”

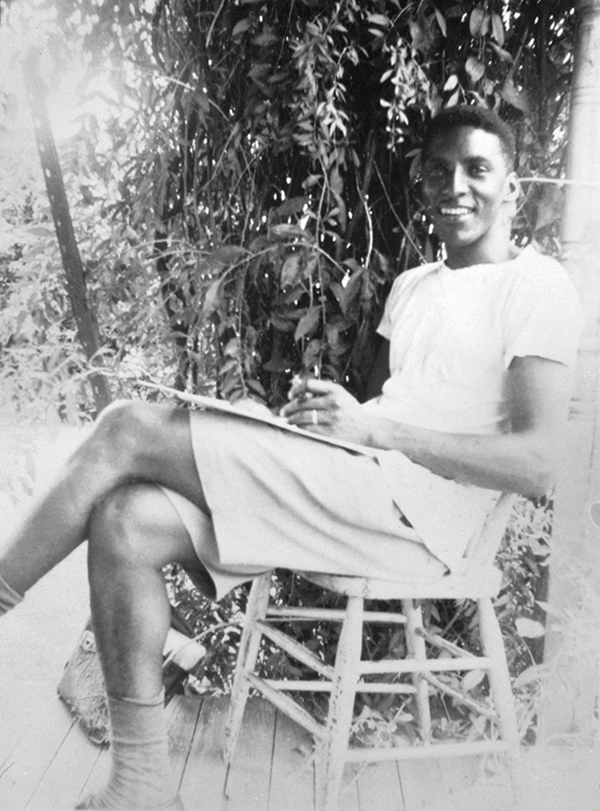

Born in 1912, Rustin learned about racism early on learned from his a Quaker grandmother in his West Chester, Pennsylvania hometown. She was also a member of the NAACP and intellectual civil rights leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson were house guests.

In high school, Rustin challenged the racially discriminatory Jim Crow laws by defying the rules to sit in the segregated balcony of a movie theater — for which he was arrested, as he recalled in the documentary Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin.

“I once went into the little restaurant next to the Warner Theatre, and—can you believe it?—there was absolute consternation. That was the first occasion in which I knew West Chester had three police cars. They surrounded the place as if we were going to destroy motherhood. I purposely got arrested, and then I made an appeal that all the black people and white people who were decent-minded should give 10 cents to get me out of jail. And I got out, because they took up a collection.”

Rustin knew he was gay in high school, he told Washington Blade reporter Peg Byron on Feb. 5, 1986. But he remained closeted until 1947 after an encounter with a child on a bus trip in the South:

“One of the reasons that I decided that I should no longer remain in the closet came from an experience I had as a black. One day, in 19…, way back as far as 1947, I walked into a bus in the South, all prepared to do what I had always done in the South. Take a seat in the rear.

As I was going by the second seat to go to the rear, a white child reached out for the red necktie I was wearing and pulled it. Whereupon its mother said, “Don’t touch a nigger.”

Something happened, and I said to myself, If I go and sit quietly in the back of that bus now, that child who was so innocent of race relations that it was going to play with me, will have seen so many blacks go in the back and sit down quietly that it’s going to end up saying, “They like it back there, I’ve never seen anybody protest against it.” That’s what people in the South would say.

So I said, I owe it to that child, not only to my own dignity, but I owe it to that child that it should be educated to know that blacks do not want to sit in the back, and therefore I should get arrested letting all these white people in the bus know that I do not accept that.

Now, it occurred to me shortly after that that it was an absolute necessity for me to declare homosexuality, because if I didn’t I was a part of the prejudice. I was aiding and abetting…

Peggy Byron: Sitting in the back, yeah…

BR: … the prejudice that was a part of the effort to destroy me. And that in the long run the only way I could be a free whole person was to face the shit.

But from my own experience I know how long it can take till you free yourself. Thirty-four years is a long time to free yourself.”

During those closeted years, he organized strikes in college, advocated to free the Scottsboro Boys, in 1936 joined the Young Communist League which fought segregation but left disillusioned when they dropped fighting Jim Crow to fight to get the US into World War II. Rustin then found two other pacifists – A. Philip Randolph, the head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and A. J. Muste, leader of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), who both became mentors.

By now Rustin was on FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s radar. Muste hired him to handle race relations. In 1941, the three pacifist socialists proposed a march on Washinton to protest segregation in the military and employment. After a meeting with President Roosevelt in the White House, FDR issued Executive Order 8802 (the Fair Employment Act) banning discrimination in defense industries and federal agencies. As an act of good faith in response, Randolph cancelled the march over Rustin’s objections. The military was finally desegregated in 1948 by President Truman, meaning black Americans fought racism and the Nazis and fascism, only to come home to Jim Crow.

Meanwhile, Rustin came to California to try to help Japanese Americans who were losing their property and their rights as the federal government imprisoned them in internment camps. He also foreshadowed the Freedom Rides by trying to desegregate interstate bus travel in 1942, for which he was arrested outside Nashville, beaten but never charged.

By 1948, the year after he came out, Rustin was well-known enough to be invited to India for an international pacifist conference.

“Mahatma Gandhi had been assassinated earlier that year, but his teachings touched Rustin in profound ways. ‘We need in every community a group of angelic troublemakers,’ he wrote after returning to the States. ‘The only weapon we have is our bodies, and we need to tuck them in places so wheels don’t turn,’” Prof. Gates writes.

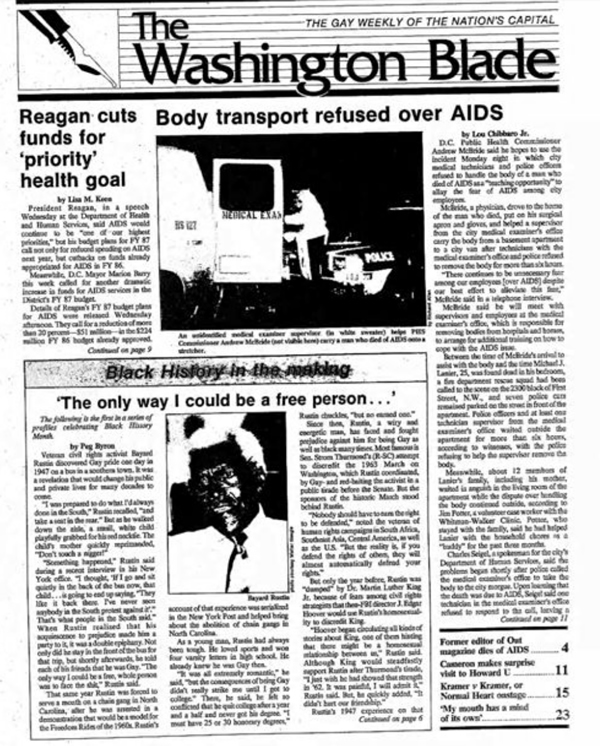

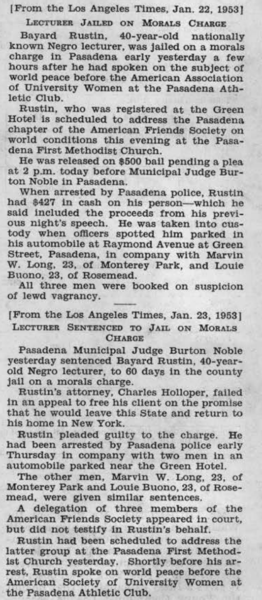

The incident for which Rustin was pardoned happened in 1953. By now a respected organizer, Rustin traveled around the country giving speeches. After a speech one January night in Pasadena, police officers found him having sex with two white men in a parked car. Rustin was arrested, sentenced to jail for 60 days and was forced to register as a sex offender for the “morals charge.”

The arrest severely damaged his career in a country terrified by McCarthyism. He was forced to cancel speaking engagements and resigned from his leadership position with Muste’s Fellowship for Reconciliation.

He struggled to find work, resorting to manual labor as a furniture mover, Naegle said later.

“I know now that for me sex must be sublimated if I am to live with myself and in this world longer,” he wrote in a March 1953 letter.

In 1955, Rustin secretly wrote “Speak Truth to Power: A Quaker Search for an Alternative to Violence.“In 1956, he found his way back into the civil rights movement, traveling to Alabama to advise Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. on how to organize his Montgomery Bus Boycott using Gandhi’s principles of non-violence. The two were introduced by Rustin’s friend Coretta Scott.

“King really had a very, very limited idea about nonviolence,” Julian Bond, who helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, told Democracy Now’s Amy Goodman. “It is Bayard Rustin who really tutored him, who said, ‘This is what you have to do.’ Rustin was horrified to see these pistols in King’s home, you know, and these armed guards around King’s home, because it just went against everything he believed in about nonviolence. If it hadn’t been for Bayard Rustin, Dr. King wouldn’t have had any understanding, I don’t think, of nonviolence. And Rustin tutored him and made him into the person we know he became.”

But that arrest record and the “open secret” of his homosexuality haunted him. Rustin was forced to resign from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference he co-founded after the powerful New York Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. threatened to tell the press that he and King were lovers.

Gay historian, John D’Emilio author of “Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin,” told Amy Goodman:

“Bayard himself was very aware that given social attitudes towards homosexuality and gay men and lesbians, he couldn’t wear it on his sleeve. He couldn’t, you know, be out there with the rainbow flag. This was before gay liberation. So Bayard himself was perfectly happy to keep this in the background and to move out of the way, if that was going to be good for the movement.

What made him unhappy and what made him feel like he had been done wrong was when people disavowed him. And there was a point, in 1960, when Rustin and Mr. Randolph and Dr. King were part of organizing major demonstrations at the presidential conventions, Republicans and Democrats, and at that point Representative Adam Clayton Powell from Harlem didn’t like the fact that these radicals, someone like Bayard Rustin, was getting so much attention and moving into his sphere in the Democratic Party.

And he put out the word to Dr. King that if you don’t distance yourself from Bayard Rustin, I am going to claim that there is something going on between the two of you. And that scared Dr. King, and Bayard made the decision to resign from his position. But he also expected at that point that he would be defended. And when he wasn’t defended, it was—it was painful. It was very painful. And he spent a couple of years, mostly—in the early ’60s, mostly involved in the peace movement rather than in the civil rights movement because of that rupture. And it’s the March on Washington that brought him back into the center of things.”

“That was around 1962,” Rustin told the Washington Blade via the special Making Gay History podcast. “And, naturally, I took the position that if people feel that I am a danger to some important movement, I would leave. But the thing which distressed me was that if… if Martin had taken the strong stand then that he took a year later, in ’63, vis-à-vis Strom Thurmond, he could have overcome it and kept me. But I understand his doing it, and I hold no grief with him about having done it. I just wish that he had shown the strength in ’62 that he showed when he backed me completely in ’63. But he was a year older and had another year’s experience.”

A. Philip Randolph brought Rustin back into the fold to organize the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom but NAACP’s Roy Wilkins saw Rustin as a liability and forced him to take a deputy position.

But then FBI Director J. Edger Hoover slipped Rustin’s arrest record to rabidly anti-gay South Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond – who had secretly fathered a child with his African-America maid. Three weeks before the march, Thurmond went public, trying to destroy the unprecedented event by denouncing Rustin as a gay communist and placing his arrest record in the congressional record.

Rustin told the Washington Blade:

“Now this became very clear to me in 1963, when I was organizing the March on Washington. And Strom Thurmond stood up in the Senate of the United States and for three-quarters of an hour, attacked me as a draft dodger, which was untrue, because I was a conscientious objector and well known as being a Quaker opposed to all violence. He attacked me as a former member of the Young Communist League, which was true. I had been. He attacked me as a homosexual. Which of course I was.

PB: You were the original commie-pinko-fag of the day, I suppose.”

BR: Yeah, exactly. Now, there were 10 leaders of that march. One of the most important Jews, the most important Catholic, the most important Protestant, Walter Reuther representing the trade union movement, and six black civil rights leaders.

When he attacked me, I had absolutely no basic apprehension and for a very good reason, because I had spent a great deal of my life defending prejudice against Catholics, against trade unions, against Jews, against blacks, against Protestants, and therefore I inwardly knew that those leaders, knowing of my history, had to come to my defense. And they did. And the important thing was that they voted that only one person should speak, and that was the founder of the march, Mr. A. Philip Randolph.”

For what spans five pages in the Congressional Record, Thurmond not only submitted the arrest record but the news articles about the arrest and conviction.

“The article states that he was convicted in 1953 in Pasadena, California, of a morals charge. The words ‘morals charge’ are true. But this is a clear-cut case of toning down the charge. The conviction was sex perversion,” says Thurmond.

“The senator is not interested in me if I were a murderer, a thief, a liar or a pervert. The senator is interested in attacking me because he is interested in destroying the movement. He will not get away with this,” Rustin said.

King and the other Big Six backed Rustin up this time because the attacks came from one of the worst Southern white supremacists. But after the march, Rustin was quietly denied his role as the seventh in the Bix Six group of civil rights leaders who called for the march: A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Jim Farmer, Whitney Young when the chief organizer of the march was disinvited to the White House to celebrate with President John F. Kennedy.

And yet, according to an extensive CNN report commemorating the 50th anniversary of the march, it was Rustin who saved the march for the organizers – from a Kennedy take over.

“The Kennedys were almost morbidly afraid of this march. They understood there’d been nothing like it,” Rep. Eleanor Holmes Norton, D-District of Columbia, who helped plan the march, told CNN.

“The Kennedy administration was afraid that if there was violence on the march, it would mean that the Civil Rights Act, which John F. Kennedy had just introduced, would never get passed,” said march planner Rachelle Horowitz. “When we first began planning the march, there was a concerted effort by the Kennedy administration to get it called off and to not let it take place.”

“They kept a watchful eye on the planning of the march,” said John Lewis, the 23-year-old elected to lead the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. “They stayed in touch with the (march) leadership,” which had been broadened to include four white leaders, representatives of the Protestant, Jewish and Catholic faiths, and civil rights advocate and United Auto Workers president Walter Reuther.

Reuther was recruited by the White House “to infiltrate the march and steer it away from radical rhetoric and direct action,” wrote Charles Euchner in his book “Nobody Turn Me Around,” about the historic march. “And so he did.”

Though JFK had come around to the idea of the march, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy’s office inside the Justice Department’s room 5110 “was the command center,” Jack Rosenthal, who was the department’s assistant press officer at the time, told CNN.

“There was a proposal on the table that Kennedy speak to the March on Washington,” march planner Courtland Cox told CNN. “And Bayard knew this would have been a disaster because it would’ve been taken over by (Kennedy) just because he’s president. It would’ve been Kennedy’s march.”

From CNN:

“So, Cox said Rustin and he excused themselves from that particular meeting and took a walk to the bathroom. Clearly flummoxed about the problem, Rustin took a sip from his back-pocket flask and came up with an idea on the fly.

“And Bayard got back into the meeting and he literally made this up,” Cox recalled. “He said that he heard … if the president spoke the Negroes were going to stone him.”

After that, the idea of Kennedy speaking at the march was never considered.”

None of the feared outbreaks of violence occurred.

“After the March on Washington was over, President Kennedy had invited us back down to the White House,” Lewis said. “He stood in the door of the Oval Office and he greeted each one of us. He was like a beaming, proud father. He was so pleased. So happy that everything had gone so well.”

Kennedy told King: “And you had a dream,” added Lewis.

Rustin’s role was overshadowed – as were his remarks at the march that August 28, 1963:

“We demand that segregation be ended in every school district in the year 1963! We demand that we have effective civil rights legislation—no compromise, no filibuster—and that include public accommodations, decent housing, integrated education, FEPC and the right to vote. What do you say? We demand the withholding of federal funds from all programs in which discrimination exists. What do you say?”

Rustin died of a perforated appendix on August 24, 1987, survived by Walter Naegle, his partner of 10 years.

One last thing, Julian Bond told Amy Goodman:

“I could not think of anybody else who at the time would have stepped forward, taken hold of this March on Washington, pull together all these hundreds of thousands of peoples, the buses, the trains. You know, I saw something just recently: They made 800,000 sandwiches. Imagine that. And it was all done at Bayard Rustin’s desire.

One thing I think we’re not hearing about Bayard Rustin is his sense of humor. He once said that Dr. King couldn’t bring vampires to a bloodbath. That was the kind of organizer Dr. King was not. But Bayard Rustin knew he was an organizer and was just wonderful at getting people to do things that they didn’t think they could do or didn’t know they wanted to do. He was just a great, great person….

I think those of us who were there in 1963 didn’t immediately realize how significant this was. As you said during the program, we didn’t see many people there early in the morning. The crowd grew and grew and grew. But even when they were all there, you had no idea how many there were. You know, you can’t look out at this mass of people and say, “This is 250,000 people.” You just have no idea who they are. And I think, for me, driving back to Atlanta later that day and then reading newspapers the next day in Atlanta and hearing what other people had to say about it, only then would we began to understand the significance of this thing—the largest gathering ever at a civil rights protest.

People came together to demand civil rights in America, and that was tremendously significant. But, as you say, if you compare these demands that Bayard read at the march with where we are today, you can see that clearly most of these things have not been achieved, and we still have a long, long way to go.”

While Rustin didn’t attend the White House meeting, he and A. Philip Randolph did make the cover of LIFE magazine.

“Rustin was one of the most important social justice activists in the U.S. in the 20th century,” says historian John D’Emilio.

That 1953 arrest record hung like an invisible chain around Rustin’s neck. Now he is really, finally free.

If you think you are eligible and would like to seek clemency, you can apply for a pardon and receive updates and information on the clemency initiative at www.gov.ca.gov/clemency

a&e features

D.C. springs back to life with new, returning events

Cherry blossoms, Rehoboth season kickoff, and more on tap

Longer and warmer days are back meaning: It’s time to get out of the house and enjoy Washington D.C.’s many events. Below are a few to check out this spring.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts will host “Making their Mark: Works from the Shah Garg Collection” until Sunday, July 26. This exhibition illustrates women artists’ vital role in abstraction, considers historical contributions, formal and material breakthroughs and intergenerational relationships among women artists over the last eight decades. For more details, visit. NMWA’s website.

Art in the Attic will host a pop-up on Saturday, March 14 at 6 p.m. at 1012 Madison St., Alexandria, Va. There will be a variety of vendors selling products across different modes of art. For more details, visit Eventbrite.

Play Play will host “Indoor Recess – The art of play” on Sunday, March 15 at 2 p.m. This event will embody classic recess energy, including opportunities to build and experience community and connections through games, movement, art stations, and creative freedom. Tickets are $12.51 and can be purchased on Eventbrite.

Spark Social will host “Gay Bar Crawl on U Street” on Friday, March 20 at 7:30 p.m. This will be a fun night out in gay D.C. with other gay people, whether you’re visiting D.C., new to the area, or just looking to expand your social circle. Many crawlers have formed lasting friendships and even romantic relationships after just one night out. Tickets are $35.88 and are available on Eventbrite.

Creative Suitland Arts Center will host “EFFERVESCENT: House of Swann” on Saturday, May 30 at 7 p.m. This will be a gay, good time where we will celebrate love, joy, wellness, and visibility for the LGBTQIA+ community. Tickets start at $17.85 and can be purchased on Eventbrite.

SWAG Works DC will host “Unapologetically Her” on Saturday, March 14 at 2 p.m. at 701 E St., S.E. This event is a powerful celebration of womanhood, resilience, creativity, and self-expression in honor of Women’s History Month. This all-women exhibition highlights the diverse voices, stories, and artistic perspectives of women who create boldly, live authentically, and stand confidently in their truth. This event is free and more details are available on Eventbrite.

9:30 Club will host “Gimme Gimme Disco: A Dance Party Inspired by ABBA” on Saturday, March 14 at 6 p.m. There will also be a “Donna Summer Power Hour – The Queen of Disco” segment during this event. It’ll be one hour of music with no skips. Tickets are available on 9:30 Club’s website.

Harder Better Faster Stronger will host “Heated Rivalry Rave” on Friday, March 20 at 9 p.m. at Howard Theatre. This event is open to all ages. Tickets are available on the theater’s website.

CAMP Rehoboth hosts its 25th annual Women’s+ FEST, April 9-12 in Rehoboth Beach, Del. Entertainers include headliner Mina Hartong, a comedian, storyteller, and founder of Lez Out Loud; and singer Yoli Mayor. There are dances, dinners, pickleball, and much more. Details and tickets at camprehoboth.org.

Also in Rehoboth Beach, the Washington Blade’s 19th annual Summer Kickoff Party is set for Friday, May 15 featuring Ashley Biden, who will accept an award on behalf of her brother Beau. State Rep. Claire Snyder-Hall will also speak. More speakers and the venue to be announced soon.

The annual D.C. Cherry Blossom Festival kicks off March 21 at DAR Constitution Hall and culminates with Petalpalooza on April 4, the day-long, outdoor street party with music and art, stretching across Navy Yard, and ending with fireworks over the Anacostia River.

a&e features

‘Queer Eye’ star Dorriene Diggs on life before and after appearing on hit show

Emotional January episode highlighted 40-year love affair with partner

Dorriene Diggs, 70, whose 40-year relationship with her domestic partner, Diane until Diane’s passing in 2020, the couple’s tense relationship with their respective parents, and Dorriene’s current living arrangement with her straight sister Jo, were the focus of a final season episode of the popular TV series “Queer Eye.”

In a recent interview with the Washington Blade, Diggs told of how her appearance on the show has impacted her life. She elaborated on the many aspects of her life experiences that she told to the five “Queer Eye” co-hosts who interviewed her and her sister in their D.C. home.

Although her parents and her partner’s parents, who have since passed away, were not accepting of their relationship, Diggs has said most of her family members at this time reacted positively to her appearance on the show.

“They loved it,” she told the Blade. “Yes, everybody that saw the show called me and said they loved the show, they really enjoyed themselves watching it.”

Through an arrangement with D.C.’s Rainbow History Project, the “Queer Eye” show featuring Diggs and her sister was presented in a special screening on a large video screen at the D.C. History Center in January.

“Dorriene, a 70-year-old Black lesbian living in Washington, D.C., had spent decades building a life with her partner while navigating silence within her own family,” a “Queer Eye” statement announcing the episode on Diggs states.

“The Fab Five did not arrive to introduce Dorriene to herself, but to help ensure her story was finally heard in full,” the statement says.

Blade: Can you tell us how your appearance on the “Queer Eye” program came about? How did they find out about you?

Diggs: You know, I still don’t have all the details. I think it was my niece, Missy. And she knows somebody there from “Queer Eye.”

Blade: So, did you first learn about it when someone from “Queer Eye” contacted you?

Diggs: No, the “Queer Eye” guy knocked on my bedroom door and started talking. I was in my bedroom watching television and the next thing I know my door opened up and there was Karamo [Karamo Brown, one of the “Queer Eye” co-hosts] with his big black cowboy hat on, opening the door grinning. … They contacted Jo first. And when they came here, they realized there was a gay woman in the house, too. Because my name was not mentioned at first. After they came here, they learned about me, because when Missy reached out to them, she reached out to them about Jo. But that doesn’t bother me. This was all about Jo in the beginning, and not me. … They started talking to me and Jo. And he said, Dorriene, ‘you’ve done so much for so many people, it’s time for someone to do something for you.’ That’s what they said. He said, ‘this is the day we’re doing it for you.’

And so, they put me and my sister up in a hotel for a week. They gave us a personal driver to take us anywhere we wanted to go. And then they took us to a bunch of places. We didn’t know why they were doing all of this. We had no idea that they were renovating the house and renovating our bedrooms. We had no idea.

Blade: What was your reaction when you saw the home renovation?

Diggs: It was amazing. And they bought us all new complete wardrobes – clothes, shoes. But most of the stuff they got me I gave away to a women’s shelter. But it was so nice. Actually, to meet the guys. I’ve been watching the show for 10 years. I have watched it from the beginning. And actually, it brought me and my sister closer – really. We’re closer now than we’ve ever been. She’s my baby sister – not the baby, but next to the baby. She’s the younger one.

Blade: What has been the reaction to your appearance on the show? Do more people now recognize you?

Diggs: Yes, yes. I’m getting phone calls and it’s almost like I’m a celebrity. And I don’t want people to make a fuss over me. All the things I did I did from the heart. I really did. And I don’t want people to think I’m more than I am. I’m just a good Christian woman that believes in giving back.

And I do. God gives me help giving. That’s what I do. And I don’t want anything in return from anyone. You know, because I know what it means to not to have. I know what it means to go to bed hungry, with no food. Going to school with holes in your shoes. I know that. I know that feeling. I’ve been there. And I promised myself as a kid I would never live like this again. And when I got bold enough to leave home, I left home at 14, and I moved in with a drag queen. Damen was his name.

Blade: Did your appearance on the show change your life and your relationship with your sister?

Diggs: Yeah, yeah, it actually did. We are actually closer now than we’ve ever been. Because, like I said, I moved away from home early and I never went back. My parents had a problem with my lifestyle. They really did. My mom looked at me with such hatred. When I was old enough to say goodbye, I never looked back. And to come back around now in the last few years after Diane died, that’s when I came back here.

And at one point I stayed with my nephew Todd and his wife – but he got killed in a car accident. I couldn’t stay at his house anymore. So, then I called Jo and told her I need to get out of here. And without hesitating she came and picked me up and brought me to her home. And I’ve been here ever since.

Blade: Can you tell a little about when it came about and how you met your partner?

Diggs: We lived on 18th Avenue in condos. I just bought one. Hers was above mine. I bought the bottom one. When my brother came over, she was getting out of her car. She was driving a Vega. And I turned to my brother and I said – this is the God’s honest truth – I said Keith, that’s the woman I’m going to spend the rest of my life with. Just like that. And he started laughing. He said, girl you’re crazy. I said I know I’m crazy, Keith, but I’m telling you that woman right there is who I’m going to spend the rest of my life with.

Blade: And when was that?

Diggs: It was 1980 actually. And then I started going to the laundry room to do my laundry. So I started talking to her. She said, ‘I’m not speaking to you.’ Isaid ‘why not?’ She said ‘because you’re nothing but a female gigolo.’ And I said I’m not dating anymore. I’m waiting for you. ‘No, you’re too fast for me.’ I said, ‘well, I’m not giving up.’

And I didn’t give up. So, I was playing an album one day and she knocked on the door and asked what I was playing, I think. I said you liked that. She said yeah. I said OK, I’ll bring it upstairs and we can listen to it together. So, when I went up there to her apartment that day and whenever I went up there, I never left.

Blade: So, your partner’s name was Diane?

Diggs: Yes, Ruth Diane Robinson. But she hated the name Ruth. So, the only people who called her Ruth were at work, the people she worked with. Everybody else called her Diane.

Blade: And how many years were you together?

Diggs: Forty. Forty years together

Blade: And where were you living with her most of the time?

Diggs: We lived in Hagerstown the longest, Hagerstown, Md. And so, if Diane hadn’t died I probably still would have been in our house in Hagerstown.

Blade: Can you tell me a little about what you were doing career wise during those years?

Diggs: I do computers. I used to do computers. And before that I cooked. I love to cook like my mom. And then I wanted to do something else. So, I taught myself computers. I taught myself how to build computers and stuff. So, then I got my own computer business called Ida One Computer Consulting. And so, we helped build computers for people.

Blade: Around when was this, in the 1980a or 1990s?

Diggs: Yes, in the 1980s. I think I stopped I would say around ’96, when I stopped. Because we both said we were going to retire at 55. And we did. We both retired at 55. And then she started diabetes. Every day I had to give her an injection because she was afraid of needles. She couldn’t give it to herself. So, I had to give her an injection every day One time, I don’t remember when, she had a mild stroke. And I had to take care of her. I’ve always taken care of her. And I don’t regret it. I never regretted it. It’s taking care of the one you love.

Blade: When was it that she passed away?

Diggs: In 2020. I found her on the kitchen floor.

Blade: How did your family and your extended family react to your relationship with Diane?

Diggs: Well, her family, oh my God, they hated me – her mother the worst. Because I put a stop to them treating her really bad. I told her mother – I said never in my life – my mother raised me well. Never disrespect someone’s mother. I said but this time I’m going to disrespect you because you are going to start treating Diane like you ought to. This is a wonderful woman and you and your son and you it’s always about your son. You never, ever say anything good about your daughter.

I said it isn’t going to happen again. You’re never going to disrespect her again. I said you take a damn good look at her because you’ll never see her again. I meant that. I grabbed Diane. I said it’s time to go. They don’t care about you.

Blade: Can you tell a little about your family?

Diggs: Yeah, I’m a triplet sister. So, it’s Dorriene, Chorine, and Chrissy — we are the triplets. So, my mom had a set of twins and a set of triplets within nine months. One of the twins died at birth. So, the other twin is Margaret.

Blade: So then how did your family react to you and Jo being on “Queer Eye”?

Diggs: Most of my family really had no problem with it.

Blade: Were you out to them?

Diggs: Oh yeah. I was never in the closet. I didn’t give a damn what people felt about me, sweetheart. I really didn’t. I didn’t care. Because I was going to be me. And for people who didn’t like it, I wasn’t living for them, I was living for me. I’ve always been out. I had a brother who was also gay, Marvin. God rest his soul, too. But he stayed in the closet. He was in the closet until he was about 55 years old.

But everything I said on the show was the truth – my account. The things that I went through with family … You can’t tell me how I felt. If they try to make mom and dad out as perfect, they weren’t perfect. They were the worst parents. That’s my account of it.

So yes, everything I said on that interview was the truth. That’s one thing people who know me know – I do not lie.

Blade: What are some of the things you like to do these days?

Diggs: I’m a sports lover. I love sports. So, my baseball season is getting ready to get started. Baseball is my favorite sport. Yes, I love baseball. I like the statistics of it. And watching the guys. I wish they had a women’s professional baseball team, honestly. … I’m a D.C. sports fan. The Wizards, the Nationals, the Mystics, the Caps. … And see, I’m a diehard Redskins fan and I refuse to call them the Commanders. They’re the Redskins. They will always be the Redskins to me. I love my sports teams.

Blade: Can you tell a little about the history of the house where you and Jo now live and where they did the filming of the “Queer Eye” show?

Diggs: Jo had a house on 17th Street, I think it was Northeast because it was over there by H Street, N.E. And I think somebody wanted to buy her house. I don’t know why she moved. So, she found this house. Because she wanted to buy something where she could buy a house straight out. She didn’t want a mortgage on another house.

Blade: What are your thoughts on being on the last season of “Queer Eye?”

Diggs: Yeah, we were the last ones. We took it out with a bang, me and Jo. That was it.

Blade: Can you say how you and Jo appearing on the show impacted your life?

Diggs: I don’t know. I’m the same person. I’ve been getting calls from people saying I saw you on the show. And friends who I haven’t seen in years have been calling. … So yeah, the show, people I haven’t seen and talked to in years have been calling. I think that’s a good thing.

a&e features

35 years after ‘Truth or Dare,’ Slam is still dancing

Salim Gauwloos on Madonna, HIV, and why he almost didn’t audition for Blond Ambition Tour

Most gay men of a certain age remember “the kiss.”

It was the moment Madonna’s dancers Salim Gauwloos and Gabriel Trupin locked lips in the hit 1991 documentary film “Truth or Dare,” which is celebrating its 35th anniversary this spring.

The kiss was hot, but what made it groundbreaking is that it appeared in a mainstream Hollywood movie that screened in suburban multiplexes across the country. This wasn’t an obscure art house film. The movie, and tour on which it was based, received months of breathless media attention all over the world for bold expressions of female empowerment and queer visibility. Madonna was threatened with arrest in Toronto for simulating masturbation on stage and Pope John Paul II urged Catholics to boycott the show, triggering a media firestorm.

“Truth or Dare” was billed as a behind-the-scenes documentary of the tour, but it quickly became clear that the real star of the show wasn’t Madonna, but rather her colorful troupe of seven backup dancers, six of whom identified as gay: Kevin Stea, Carlton Wilborn, Luis Xtravaganza Camacho, Jose Gutierez Xtravaganza, Gauwloos, and Trupin; Oliver Crumes III identifies as straight.

We saw them party and march in the New York City Pride parade. They were unabashedly queer at a dangerous time — before protease inhibitors began to stem the AIDS plague and before most celebrities and politicians embraced the gay community in any real way. Being out in 1991 carried major risks to career and reputation.

Enter Gauwloos, one of those brave dancers who vogued his way into the hearts of countless gay men entranced by his handsome looks, his stage presence, and dance skills.

Gauwloos — known then and now as “Slam”— sat down with the Blade to talk Madonna, the lasting impact of “Truth or Dare,” the public disclosure of his HIV status, and plans for a new book on his life.

His story is fascinating — from growing up in Europe to dancing in New York to landing the gig of a lifetime with Madonna. He performed on that tour while secretly HIV positive and went without medical treatment for 10 years because he was living in the United States as an undocumented immigrant. Not even Madonna knew of his HIV status. Two other dancers on the tour were also HIV positive but no one talked about it. Ironically, Madonna was singing “Express Yourself” and advocating for condom use during her concerts yet backstage three of her dancers were secretly positive.

“A lot of people were dying so I wasn’t going to tell Madonna I had HIV,” said Slam, now 57. “And the others didn’t either. It wasn’t the moment to do it. She used to make speeches about Keith Haring and AIDS and I thought it’s going to be me next.”

Gabriel Trupin died of AIDS in 1995. Slam was diagnosed at age 18 in 1987, a frightening time when a positive test result often meant a death sentence. He booked the “Blond Ambition Tour” at age 21 after moving to New York. His friends encouraged him to audition but Slam resisted because he wasn’t a big Madonna fan.

“It was crazy, everyone wanted that job,” he said, “but I wanted to dance with Janet Jackson and Paula Abdul.” He listened to his friends and shortly after the audition, Slam received a call from Madonna herself inviting him to join the tour.

“We all wanted to be stars but not even Madonna knew how big that tour would become. The way it was choreographed and directed, the stars aligned. … It never looks dated even today.”

The world tour kicked off in Japan in April 1990 then moved to the United States and Europe, stirring controversy wherever it went. There was the iconic cone bra; the aforementioned simulated masturbation during “Like a Virgin”; and religious imagery that offended many Catholic groups and the Vatican.

And the controversy didn’t end with the tour. Cameras were rolling throughout the tour for what Slam thought would be a “video memory” for Madonna. But as the tour unfolded, director Alek Keshishian reportedly became more interested in what was happening behind the scenes so plans for mere tour footage were expanded into a full documentary.

“We were young and partying and didn’t really know what was going on,” Slam said. “You live in this celebrity bubble and you sign a paper – I don’t even know what I signed.”

In 1992, Kevin, Oliver, and Gabriel sued Madonna for invasion of privacy and fraud claiming she used some footage without their consent. They claim they were told nothing would be included in the film that they didn’t want to be seen. In one specific incident, Gabriel alleged that he told producers he didn’t want the scene of him kissing Slam to be in the film as he wasn’t fully out.

“Gabriel was forcibly outed,” in the movie, Kevin said in a 2016 interview.

Slam did not join his colleagues in the lawsuit.

“I couldn’t sue because I was illegal but I wasn’t ever going to sue,” Slam said. “I’m not a suing kind of person. But good for them, they fought for it and won. A lot of people don’t have the balls to sue Madonna.” The suit was settled two years later for an undisclosed sum.

“We were all conflicted about the kiss,” he said with a laugh. “The kiss, oh my God, my boyfriend is going to kill me! Belgian stress!”

Beyond worrying about his boyfriend’s reaction, Slam had concerns about the impact of being openly gay on his modeling career.

“In 1990, you couldn’t get high fashion campaigns as an openly gay model,” he said. “I was worried about that. I couldn’t get a campaign because I was gay. My agency told me to say I was straight and it was just a game.”

In 2016, pegged to the 25th anniversary of “Truth or Dare,” the surviving six dancers filmed a documentary about their lives post-Madonna titled “Strike A Pose.” In it, Slam publicly revealed his HIV status for the first time in an emotional scene with his former colleagues.

“I found the strength to tell the world I have HIV,” he recalls. “I was scared but I felt brave. The outcome and messages were beautiful. After I saw ‘Strike A Pose,’ I knew we gave people hope. And not just for gay people.”

He was infected in 1987 but didn’t get treated until 1997. After the tour ended, he said he went into a depression and his agency dropped him.

“I was partying too much after the tour,” he recalls. “I made a decision to live as an illegal alien.” In 1997, Slam collapsed and was rushed to the hospital with pneumonia.

“They started treating me and thank God the new HIV drugs were out, the cocktails, it took me a couple months to get better.”

Madonna didn’t participate in “Strike A Pose” and Slam said he hasn’t seen or spoken to her since the end of the tour. He said he had no idea of the impact “Truth or Dare” would have.

“You look at this movie in 1991 and you don’t think it’s going to be such a big thing and 35 years later it’s still helping people,” he said. “It was helpful for people who felt alone at that time. It was such an important documentary.

“I don’t think younger gay people realize how important Madonna was to gay and queer visibility — she was a big part of it. We showed the world it’s OK to be gay and that was the great message of this movie.”

He noted that, decades later, many of his friends have transgender kids and that queer culture is represented in much of mainstream pop culture.

“It’s amazing how far we’ve come,” he said. “I know we’ll always be marginalized but we have come so far. I’m really proud of our community. The current nightmare will be over and I do believe that things will get better.”

Referencing President Trump’s attacks on the LGBTQ community and crackdown on immigration, Slam described the situation in the U.S. today as “sad.”

“Everything is such a mess,” he said. “Some of these people have lived here 30-40 years and they take you out of your home. I can’t even imagine. It breaks my heart. When I was illegal it was a different story.”

Slam met his husband, Facundo Gabba, who’s from Argentina, in 2000, and he helped him get a legal case together to win citizenship. He filed a case in 2001 and was told there was a 99 percent chance he wouldn’t be permitted to stay in the United States because they weren’t allowing HIV-positive immigrants to remain in the country. But he got his green card anyway in 2005 and became a U.S. citizen in 2012.

Today, Slam and Gabba live in Brooklyn, though they travel a lot because “I can’t take the cold.” The couple married in Argentina in 2010 and in the U.S. in 2016.

Slam is still dancing and working as a choreographer. He’s teaching at a contemporary dance festival in Vienna in July and even offers online lessons via Salimdans.com.

As a longtime HIV survivor, Slam is dedicated to a healthful lifestyle.

“You have to keep moving; when you move you stay healthy,” he says. “Dance heals everything. I do yoga, I eat healthy and clean as possible. I don’t watch much TV … I try to stay healthy and positive. If I absorb all of the negativity I would be sick.”

In addition to his ongoing work in dance and choreography, Slam is in the early stages of writing a book about his extraordinary life and pioneering career.

“I always knew I had a book inside of me. I want to talk about my HIV status. I know I can inspire more people. I want to tell even more secrets in the book; secrets are a poison so I want to tell everything.”

Among those secrets, he notes, is a desire to write about his strict Muslim father and the years he spent as an undocumented immigrant in America.

“Those are the things I want to talk about, the struggles. It’s a love story, hope and resilience. I know it will help people.”

As for his friends from the tour, Slam says he remains in contact with Gabriel’s mother and José Xtravaganza is his best friend. Baltimore’s Center Stage theater is currently developing a new musical about Xtravaganza’s life. And Slam said he occasionally talks to Oliver, though “he still can’t pronounce Sandra Bernhard’s name.”

At the end of our interview, Slam indulged a round a rapid fire questions:

• Favorite song to perform in the “Blond Ambition” tour? “Express Yourself.”

• Aside from Madonna, who was your favorite artist you worked with? Toni Braxton in “Aida” on Broadway.

• Favorite Madonna song? “Live to Tell”

• Favorite Madonna video? “Bedtime Stories”

• What’s more stressful: performing in a concert or performing on the VMAs? “Both, because we always had to be perfect.”

• Did you go to Madonna’s recent “Celebration” tour? “I didn’t see the show but I saw clips online.”

• What do you remember most about performing “Vogue” at the VMAs? “It was nerve-racking for them to flip those fans.”

• When was the last time you vogued? “I teach classes so a couple weeks ago.”

-

Health4 days ago

Health4 days agoToo afraid to leave home: ICE’s toll on Latino HIV care

-

Movies4 days ago

Movies4 days agoIntense doc offers transcendent treatment of queer fetish pioneer

-

Colombia3 days ago

Colombia3 days agoClaudia López wins primary in Colombian presidential race

-

The White House3 days ago

The White House3 days agoTrump will refuse to sign voting bill without anti-trans provisions