Arts & Entertainment

Mark of the ‘Beast’

Novelist Louis Bayard explores Brazil circa 1914 in new adventure

In Louis Bayard’s new novel, Col. Theodore Roosevelt and his son, Kermit, are kidnapped by a mysterious Amazonian tribe in Brazil circa 1914 and must find and kill a ravenous beast to survive. (Washington Blade photo by Michael Key)

‘Roosevelt’s Beast’

By Louis Bayard

Henry Holt and Company

Available March 18

320 pages

Hardcover

$27

Appearances:

Politics & Prose

5015 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

March 23

5 p.m.

One More Page Books

2200 N. Westmoreland St. No. 101

Arlington, VA

March 27

7 p.m.

Listen for Bayard on the “Diane Rehm Show” (WAMU 88.5)

On March 24 at 11 a.m.

Details at louisbayard.com

Washington novelist Louis Bayard, whose new work “Roosevelt’s Beast” will be released Tuesday, spent a whirlwind hour with the Blade two weeks ago touching on everything from how he got started and how his career developed to what he tells young writers in his classes at George Washington University and how he wrestled the “Beast” that is his latest novel.

Bayard, 50, and his partner of 26 years, Don Montuori, are married and have two sons, ages 13 and 11. They live in Capitol Hill. Bayard, born in Albuquerque but raised mostly in Springfield, Va., moved to Washington in 1988, worked on the Hill and later did PR for various environmental groups through the ‘90s. His first novel, the gay-themed “Fool’s Errand,” was published by gay press Alyson Books in 1999. “Roosevelt’s Beast” is his sixth book. He’s not sure how many books he’s sold total, but upon consulting with his publisher, estimates the number to be about 100,000.

His comments have been slightly edited for length.

WASHINGTON BLADE: You went to Princeton and Joyce Carol Oates is quoted on the back of your new book. Did you take her creative writing course?

LOUIS BAYARD: Yes. She was also my adviser.

BLADE: What did you learn from her?

BAYARD: She was a very exacting reader, so it forced me to think about every word I write and I really do sweat every word. You do sometimes start to think over the course of a book, “Does this really matter,” but I revise and review and I think it’s because I had that kind of very hard eye that sniffs out deceit and flabbiness and all the stuff that can go wrong in prose. I don’t recall any specific lesson. I just recall how nice it was to feel understood by somebody of her caliber.

BLADE: Was it a big leap from Alyson to HarperCollins, which published your third book “Mr. Timothy”? How did that play out?

BAYARD: Alyson was one of the few places that would take an un-agented manuscript. The first book was gay-themed and they were a gay publisher so I just thought, “Why not take it straight to them?” It was a good fit for what I was doing. … But then when I had an idea for this book about Tiny Tim (2003’s “Mr. Timothy”), I thought, “I don’t just want this to be plunked on the gay shelf at Borders.” There was that sense of being ghettoized by virtue of being with a gay press. You go on that one shelf in the back of the store. I wanted this out in the front, so I found an agent, finally, after several tries, and he pitched it to the big houses and one of them bit.

BLADE: Would you call that your big break?

BAYARD: I guess you’d call it a break. It seemed like a break at the time. It was a break toward the mainstream, I guess, but I never felt like I’ve left the gay sensibility entirely behind.

BLADE: Do you enjoy teaching?

BAYARD: I do. I wish it paid a little more honestly. I’m there as an adjunct where you’re paid some ridiculous pittance for a lot of work, but I have other income sources. I just teach one fiction writing class.

BLADE: What do you tell your students?

BAYARD: To me, every student is a little different and they all bring something a little different so I just try to create a space where they can experiment and find their own voices. … It’s a workshop, so I’m basically like Socrates there in the midst, throwing out questions and making them think about things.

BLADE: About how many would you say have been good enough to get published?

BAYARD: Of the three years I’ve been doing it, I would say, maybe there were about that many who had the potential to do it. It would really be about desire. Actually the best writer I know of, and I can’t even remember her name offhand, but she was exceptional but actually was the least interested in pursuing it. I kept saying, “You really need to try this,” but she kept saying, “Well, I’m going to Europe” and she had all these plans. She just didn’t seem excited about it. That’s where perseverance pays off as much as anything.

BLADE: You went from gay contemporary fiction into several novels of historical fiction. How did that creative decision come about?

BAYARD: I thought it was an accident when I had this idea to see what became of Tiny Tim, but it achieved a certain amount of success so they kind of wanted me to keep doing that and I’ve come to believe it was a fortuitous accident because it really is the genre that’s most suited to me. I kind of fought it for a while, but now I’ve accepted that I stumbled into the right place.

BLADE: Does writing fiction about people who really lived, like Theodore Roosevelt in your new book, make it seem more real? What is the appeal?

BAYARD: I think there’s both a promise and a challenge that comes with that. People will recognize then name … and perhaps be intrigued as a result, but the challenge is that then you have to make this very well-known character come alive in your own way. It has to be convincing and plausible. You kind of have to work with people’s expectations but also make it a character that lives on the page.

BLADE: Do you have history geeks call you out on minutiae?

BAYARD: Oh yes.

BLADE: What do you say?

BAYARD: Sorry! Old ladies will e-mail me and say something like, “But there were no poinsettias in English drawing rooms in 1842” or “mockingbirds hadn’t migrated as far north as the Hudson Valley by 1830,” and you just go, “Sorry — that’s why I’m a novelist. I get to make things up or change things around if they don’t work.” I try to be as historically accurate as possible, but I think the story’s more important than the history.

BLADE: Is the line between contemporary literature and popular fiction sometimes arbitrary? Where do you feel your books fall on the continuum?

BAYARD: I think of them as sort of a hybrid between literary and genre. I have genre elements, like a mystery or thriller plot, but — what can I say without sounding self regarding? — I do take care with the language and use literary devices. I’m fine with people who just consider them entertainments. I don’t think of them as literature with a capitol L, but I do write to entertain. That’s my first aim. I want it to be a good book, but want you to feel good about yourself the next morning.

BLADE: What’s the gulf like between the two worlds? In music, for instance, there seems to be a pretty sizable gulf between classical and pop.

BAYARD: I think the gulf is narrowing because we’re seeing people like Michael Chabon and Colson Whitehead who are literary figures but who are also very deliberately writing in genre and I love the idea of breaking down that wall because I think it’s a silly distinction. I’m thinking of Richard Price who has written these great crime novels set in New York like “Clockers” and “Lush Life.” They’re police procedurals, they’re genre, but they’re such brilliant dissections of our society and they’re so ambitious, so beautifully crafted. The dialogue is extraordinary and I think he should be considered a literary artist.

BLADE: You wrote two gay-themed contemporary novels set in Washington. What kind of reactions did you get? Did people assume they were roman a clefs?

BAYARD: I guess there was a little bit of that assumption.

BLADE: But you had a sense that people outside of your acquaintance circle were reading and enjoying them?

BAYARD: I think so. Periodically I hear from them. “Fool’s Errand” seems to have a very small but enthusiastic cult. There may only be 12 of them but I hear from them on the order of once a year or so. They were conceived as entertainments so I didn’t expect them to be embraced as the next coming of Edmund White or something. I did worry that when I moved onto other things, that it would be seen as turning my back on gay readers and gay bookstores.

BLADE: Did anybody float that theory to you?

BAYARD: No, I probably projected it onto them. I maintain that my books since then still have a gay vibe and I’ve had gay characters in other books. Kermit Roosevelt in this new book isn’t gay, but he’s not really about heteronormative ideals. I don’t write about he-men.

BLADE: Was there a sense that you started out writing what you knew, then graduated onto tougher projects?

BAYARD: Oh, that’s interesting. “Fool’s Errand” required zero research. I just drew from my own life and my friends’ lives. “Mr. Timothy” was really the first book where I had to come up with a whole other world, but it was a challenge I wanted to embrace. There’s only so much you can squeeze out of your own life and I’m pretty quiet honestly. Not a lot of drama.

BLADE: How do you deem success for these various projects? Is there a sales threshold you like to hit?

BAYARD: To me, success is earning back the advance they give me.

BLADE: Now that you have several under your belt, do you feel freer to experiment? The book world seems like a jungle these days. Do you have any sense that if you wrote something that bombed, they would give you another shot?

BAYARD: No, I don’t think they would. This was the second of a two-book deal so after this I’m a free agent.

BLADE: So do you feel a lot of pressure?

BAYARD: The pressure is that I want to keep doing this indefinitely so I feel obliged to get a certain number of nice critical reviews and sell a certain amount. But there are plenty of mid-list writers who earn back their advances and are doing everything they need to do but are being dropped from publishing houses. It’s a little scary. The whole business is contracting. They seem to want more high concept stories — you know, werewolves and vampires and what not. Zombies. So you do sort of feel you’re dancing as fast as you can most of the time.

BLADE: Sounds nerve wracking.

BAYARD: It is, but it’s the business too, not just authors. Publishers are shit scared and nobody knows anything. Which can be freeing in a way. You think, “Well, I may not know anything, but I know as much as they do.” What’s commercial? Nobody expected “The Da Vinci Code” to become the monster hit that it became, so I don’t know. It’s a weird time.

BLADE: Where does the drive come from? Did you always want to do this?

BAYARD: Oh, I’ve known since I was 10 on some level.

BLADE: What was the appeal?

BAYARD: Well, every writer starts as a reader. I loved reading from an early age, though my kids don’t. I always have and it’s the thing I love more than anything. So you start as a reader then you realize you want to create the same effect on someone else that these writers did on you. It was really in high school that I first started finding a voice of some kind. … My first credits were in gay magazine called Genre. Are they still around?

BLADE: Well, it’s funny you should mention that. (Editor’s note:Genre and Washington Blade previously had the same owners.)

BAYARD: Eventually my first novel came out and kind of went nowhere and there were a couple years where I wasn’t writing much at all, but there was always part of me that kept coming back to this. I think the surest test of a vocation is that you keep going forward even in the face of rejection. Even if it’s not clear that anybody in the world wants to read what you write.

BLADE: How tedious is the actual process? Are there points along the way you want to rip your hair out or is there joy in the problem solving?

BAYARD: Both. It’s an unstable compound of all those things. I wish it got easier. I used to think it would, but it really doesn’t.

BLADE: What’s the most common mistake you see in your students?

BAYARD? A lot of them are very entranced with words. They’re just discovering word power so they write these amazing, gorgeous, beautiful sentences. … A young writer throws everything at you because they want to impress and stun and overwhelm but. As I get older, I’m realizing you need less and less. Oddly enough, they neglect story. It’s amazing how many of them don’t know what their story is.

BLADE: Lots of authors might have one or two good books in them, but to keep doing this over many years is quite a feat. Yet it seems you’re heading down that path. Was there a point you felt you’d turned a corner?

BAYARD: Oh, I never feel I’ve made it. Yes, there are things that might look like success, but for me, it’s a constantly moving goalpost. I used to say all I wanted was to get reviewed in the New York Times. My second book was, but then I ended up in a depressive tailspin the week after. It’s a hard thing to chase because you never feel completely successful.

BLADE: What’s next?

BAYARD: Probably a young-adult novel set in the Great Depression. That’s about all I can say. It would be another jump, but it’s the only growth sector in publishing. I’m reading a lot of young-adult stuff and I’ve been very impressed by the quality. Some of it’s really excellent.

Movies

Van Sant returns with gripping ‘Dead Man’s Wire’

Revisiting 63-hour hostage crisis that pits ethics vs. corporate profits

In 1976, a movie called “Network” electrified American moviegoers with a story in which a respected news anchor goes on the air and exhorts his viewers to go to their windows and yell, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!”

It’s still an iconic line, and it briefly became a familiar catch phrase in the mid-’70s lexicon of pop culture, the perfect mantra for a country worn out and jaded by a decade of civil unrest, government corruption, and the increasingly powerful corporations that were gradually extending their influence into nearly all aspects of American life. Indeed, the movie itself is an expression of that same frustration, a satire in which a man’s on-the-air mental health crisis is exploited by his corporate employers for the sake of his skyrocketing ratings – and spawns a wave of “reality” programming that sensationalizes outrage, politics, and even violence to turn it into popular entertainment for the masses. Sound familiar?

It felt like an exaggeration at the time, an absurd scenario satirizing the “anything-for-ratings” mentality that had become a talking point in the public conversation. Decades later, it’s recognized as a savvy premonition of things to come.

This, of course, is not a review of “Network.” Rather, it’s a review of the latest movie by “new queer cinema” pioneer Gus Van Sant (his first since 2018), which is a fictionalized account of a real-life on-the-air incident that happened only a few months after “Network” prompted national debate about the media’s responsibility in choosing what it should and should not broadcast – and the fact that it strikes a resonant chord for us in 2026 makes it clear that debate is as relevant as ever.

“Dead Man’s Wire” follows the events of a 63-hour hostage situation in Indianapolis that begins when Tony Kiritsis (Bill Skarsgård) shows up for an early morning appointment at the office of a mortgage company to which he is under crippling debt. Ushered into a private office for a one-on-one meeting with Dick Hall (Dacre Montgomery), son of the brokerage’s wealthy owner, he kidnaps the surprised executive at gunpoint and rigs him with a “dead man’s wire” – a device that secures a shotgun against a captive’s head that is triggered to discharge with any attempt at escape – before calling the police himself to issue demands for the release of his hostage, which include immunity for his actions, forgiveness of his debt, reimbursement for money he claims was swindled from him by the company, and an apology.

The crisis becomes a public spectacle when Kiritsis subjects his prisoner to a harrowing trip through the streets back to his apartment, which he claims is wired with explosives. As the hours tick by, the neighborhood surrounding his building becomes a media circus. Realizing that law enforcement officials are only pretending to negotiate while they make plans to take him down, he enlists the aid of a popular local radio DJ Fred Heckman (Colman Domingo) to turn the situation into a platform for airing his grievances – and for calling out the predatory financial practices that drove him to this desperate situation in the first place.

We won’t tell you how it plays out, for the sake of avoiding spoilers, even though it’s all a matter of public record. Suffice to say that the crisis reaches a volatile climax in a live broadcast that’s literally one wrong move away from putting an explosion of unpredictable real-life violence in front of millions of TV viewers.

In 1977, the Kiritsis incident certainly contributed to ongoing concerns about violence on television, but there was another aspect of the case that grabbed public attention: Kiritsis himself. Described by those who knew him as “helpful,” “kind,” and a “hard worker,” he was hardly the image of a hardened criminal, and many Americans – who shared his anger and desperation over the opportunistic greed of a finance industry they believed was playing them for profit – could sympathize with his motives. Inevitably, he became something of a populist hero – or anti-hero, at least – for standing up to a stacked system, an underdog who spoke things many of them felt and took actions many of them wished they could take, too.

That’s the thing that makes this true-life crime adventure uniquely suited to the talents of Van Sant, a veteran indie auteur whose films have always specialized in humanizing “outsider” characters, usually pushed to the fringes of society by circumstances only partly under their own control, and often driven to desperate acts in pursuit of an unattainable dream. Tony Kiritsis, a not-so-regular “Joe” whose fumbling efforts toward financial security have been turned against him and seeks only recompense for his losses, fits that profile to a tee, and the filmmaker gives us a version of him (aided by Skarsgård’s masterfully modulated performance) that leaves little doubt that he – from a certain point of view, at least – is the story’s unequivocal protagonist, no matter how “lawless” his actions might be.

It helps that the film gives us much more exposure to Kiritsis’ personality than could be seen merely during the historic live broadcast that made him infamous, spending much of the movie focused on his interactions with Hall (performed with equally well-managed nuance by Montgomery) during the two days spent in the apartment, as well as his dealings with DJ Heckman (rendered with savvy and close-to-the-chest cageyness by Domingo); for balance, we also get fly-on-the-wall access to the interplay outside between law enforcement officials (including Cary Elwes’ blue collar neighborhood cop) as they try to navigate a potentially deadly situation, and to the jockeying of an ambitious rookie street reporter (Myha’la) with the rest of the press for “scoops” with each new development.

But perhaps the interaction that finally sways us in Kiritsis’s favor takes place via phone with his captive’s mortgage tycoon father (Al Pacino, evoking every unscrupulous, amoral mob boss he’s ever played), who is willing to sacrifice his own son’s life rather than negotiate a deal. It’s a nugget of revealed avarice that was absent in the “official” coverage of the ordeal, which largely framed Kiritsis as mentally unstable and therefore implied a lack of credibility to his accusations against Meridian Mortgage. It’s also a moment that hits hard in an era when the selfishness of wealthy men feels like a particularly sore spot for so many underdogs.

That’s not to say there’s an overriding political agenda to “Dead Man’s Wire,” though Van Sant’s character-driven emphasis helps make it into something more than just another tension-fueled crime story; it also works to raise the stakes by populating the story with real people instead of predictable tropes, which, coupled with cinematographer Arnaud Potier’s studied emulation of gritty ‘70s cinema and the director’s knack for inventive visual storytelling, results in a solid, intelligent, and darkly humorous thriller – and if it reconnects us to the “mad-as-hell” outrage of the “Network” era, so much the better.

After all, if the last 50 years have taught us anything about the battle between ethics and profit, it’s that profit usually wins.

Books

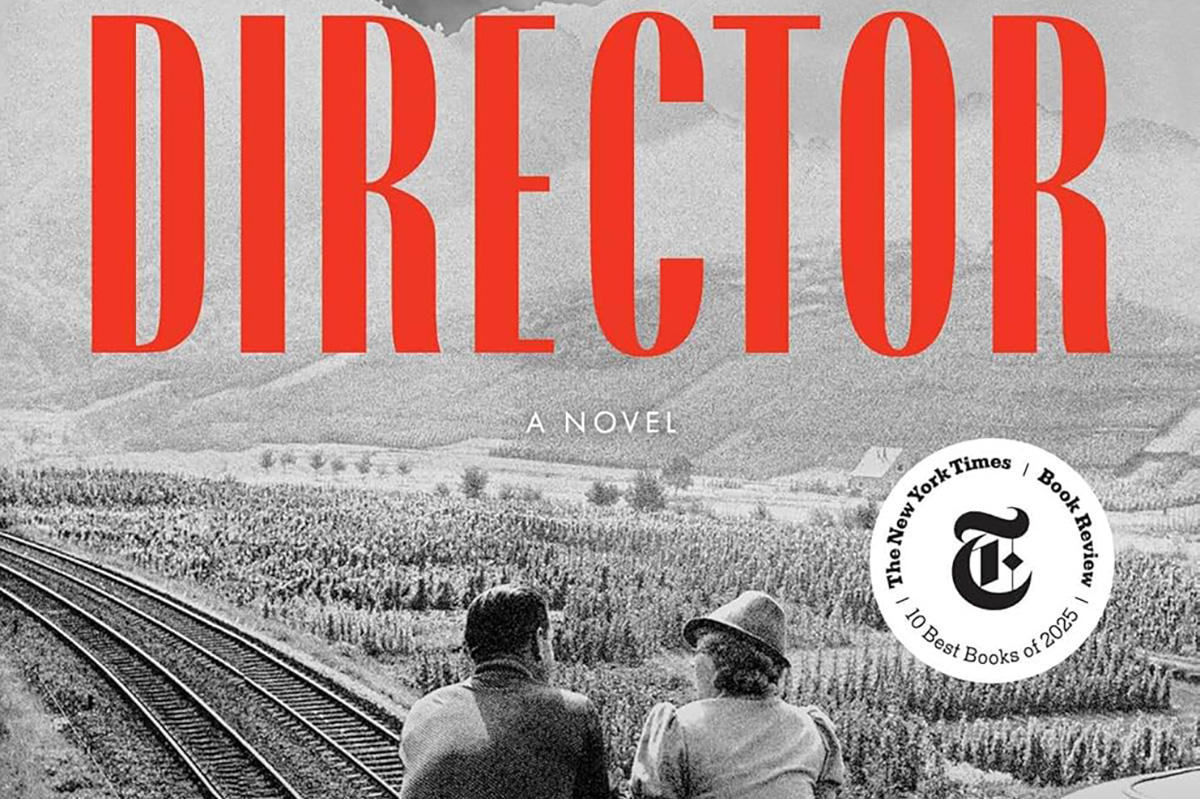

‘The Director’ highlights film director who collaborated with Hitler

But new book omits gay characters, themes from Weimar era

‘The Director’

By Daniel Kehlmann

Summit Books, 2025

Garbo to Goebbels, Daniel Kehlmann’s historical novel “The Director” is the story of Austrian film director G.W. Pabst (1885-1967) and his descent down a crooked staircase of ambition into collaboration with Adolph Hitler’s film industry and its Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. Kehlmann’s historical fiction is rooted in the world of Weimar German filmmaking and Nazi “Aryan” cinema, but it is a searing story for our challenging time as well.

Pabst was a legendary silent film director from the Weimar Republic’s Golden Era of filmmaking. He “discovered” Greta Garbo; directed silent screen star Louise Brooks; worked with Hitler’s favored director Leni Riefenstahl (“Triumph of the Will”); was a close friend of Fritz Lang (“Metropolis”); and lived in Hollywood among the refugee German film community, poolside with Billy Wilder (“Some Like it Hot”) and Fred Zinnemann (“High Noon”) — both of whose families perished in the Holocaust.

Yet, Pabst left the safety of a life and career in Los Angeles and returned to Nazi Germany in pursuit of his former glory. He felt the studios were giving him terrible scripts and not permitting him to cast his films as he wished. Then he received a signal that he would be welcome in Nazi Germany. He was not Jewish.

Kehlmann, whose father at age 17 was sent to a concentration camp and survived, takes the reader inside each station of Pabst’s passage from Hollywood frustration to moral ruin, making the incremental compromises that collectively land him in the hellish Berlin office of Joseph Goebbels. In an unforgettably phantasmagoric scene, Goebbels triples the stakes with the aging filmmaker, “Consider what I can offer you….a concentration camp. At any time. No problem,” he says. “Or what else…anything you want. Any budget, any actor. Any film you want to make.” Startled, paralyzed and seduced by the horror of such an offer, Pabst accepts not with a signature but a salute: “Heil Hitler,” rises Pabst. He’s in.

The novel develops the disgusting world of compromise and collaboration when Pabst is called in to co-direct a schlock feature with Hitler’s cinematic soulmate Riefenstahl. Riefenstahl, the “Directress” is making a film based on the Fuhrer’s favorite opera. She is beautiful, electric and beyond weird playing a Spanish dancer who mesmerizes the rustic Austrian locals with her exotic moves. The problem is scores of extras will be needed to surround and desire Fraulein Riefenstahl. Mysteriously, the “extras” arrive surprising Pabst who wonders where she had gotten so many young men when almost everyone was on the front fighting the war. The extras were trucked in from Salzburg, he is told, “Maxglan to be precise.” He pretends not to hear. Maxglan was a forced labor camp for “racially inferior” Sinti and Roma gypsies, who will later be deported from Austria and exterminated. Pabst does not ask questions. All he wants is their faces, tight black and white shots of their manly, authentic, and hungry features. “You see everything you don’t have,” he exhorts the doomed prisoners to emote for his camera. Great art, he believes, is worth the temporal compromises and enticements that Kehlmann artfully dangles in the director’s face. And it gets worse.

One collaborates in this world with cynicism born of helpless futility. In Hollywood, Pabst was desperate to develop his own pictures and lure the star who could bless his script, one of the thousands that come their way. Such was Greta Garbo, “the most beautiful woman in the world” she was called after being filmed by Pabst in the 1920s. He shot her close-ups in slow motion to make her look even more gorgeous and ethereal. Garbo loved Pabst and owed him much, but Kehlmann writes, “Excessive beauty was hard to bear, it burned something in the people around it, it was like a curse.”

Garbo imagined what it would be like to be “a God or archangel and constantly feel the prayers rising from the depths. There were so many, there was nothing to do but ignore them all.” Fred Zinnemann, later to direct “High Noon”, explains to his poolside guest, “Life here (in Hollywood) is very good if you learn the game. We escaped hell, we ought to be rejoicing all day long, but instead we feel sorry for ourselves because we have to make westerns even though we are allergic to horses.”

The texture of history in the novel is rich. So, it was disappointing and puzzling there was not an original gay character, a “degenerate” according to Nazi propaganda, portrayed in Pabst’s theater or filmmaking circles. From Hollywood to Berlin to Vienna, it would have been easy to bring a sexual minority to life on the set. Sexual minorities and gender ambiguity were widely presented in Weimar films. Indeed, in one of Pabst’s films “Pandora’s Box” starring Louise Brooks there was a lesbian subplot. In 1933, when thousands of books written by, and about homosexuals, were looted and thrown onto a Berlin bonfire, Goebbels proclaimed, “No to decadence and moral corruption!” The Pabst era has been de-gayed in “The Director.”

“He had to make films,” Kehlmann cuts to the chase with G.W. Pabst. “There was nothing else he wanted, nothing more important.” Pabst’s long road of compromise, collaboration and moral ruin was traveled in small steps. In a recent interview Kehlmann says the lesson is to “not compromise early when you still have the opportunity to say ‘no.’” Pabst, the director, believed his art would save him. This novel does that in a dark way.

(Charles Francis is President of the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., and author of “Archive Activism: Memoir of a ‘Uniquely Nasty’ Journey.”)

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Theater

Swing actor Thomas Netter covers five principal parts in ‘Clue’

Unique role in National Theatre production requires lots of memorization

‘Clue: On Stage’

Jan. 27-Feb. 1

The National Theatre

1321 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

thenationaldc.com

Out actor Thomas Netter has been touring with “Clue” since it opened in Rochester, New York, in late October, and he’s soon settling into a week-long run at D.C.’s National Theatre.

Adapted by Sandy Rustin from the same-titled 1985 campy cult film, which in turn took its inspiration from the popular board game, “Clue” brings all the murder mystery mayhem to stage.

It’s 1954, the height of the Red Scare, and a half dozen shady characters are summoned to an isolated mansion by a blackmailer named Mr. Boddy where things go awry fairly fast. A fast-moving homage to the drawing room whodunit genre with lots of wordplay, slapstick, and farce, “Clue” gives the comedic actors a lot to do and the audience much to laugh at.

When Netter tells friends that he’s touring in “Clue,” they inevitably ask “Who are you playing and when can we see you in it?” His reply isn’t straightforward.

The New York-based actor explains, “In this production, I’m a swing. I never know who’ll I play or when I’ll go on. Almost at any time I can be called on to play a different part. I cover five roles, almost all of the men in the show.”

Unlike an understudy who typically learns one principal or supporting role and performs in the ensemble nightly, a swing learns any number of parts and waits quietly offstage throughout every performance just in case.

With 80 minutes of uninterrupted quick, clipped talk “Clue” can be tough for a swing. Still, Netter, 28, adds, “I’m loving it, and I’m working with a great cast. There’s no sort of “All About Eve” dynamic going on here.”

WASHINGTON BLADE: Learning multiple tracks has got to be terrifying.

THOMAS NETTER: Well, there certainly was a learning curve for me. I’ve understudied roles in musicals but I’ve never covered five principal parts in a play, and the sheer amount of memorization was daunting.

As soon as I got the script, I started learning lines character by character. I transformed my living room into the mansion’s study and hallway, and got on my feet as much as I could and began to get the parts into my body.

BLADE: During the tour, have you been called on to perform much?

NETTER: Luckily, everyone has been healthy. But I was called on in Pittsburgh where I did Wadsworth, the butler, and the following day did the cop speaking to the character that I was playing the day before.

BLADE: Do you dread getting that call?

NETTER: Can’t say I dread it, but there is that little bit of stage fright involved. Coming in, my goal was to know the tracks. After I’d done my homework and released myself from nervous energy, I could go out and perform and have fun. After all, I love to act.

“Clue” is an opportunity for me to live in the heads of five totally different archetype characters. As an actor that part is very exciting. In this comedy, depending on the part, some nights it’s kill and other nights be killed.

BLADE: Aside from the occasional nerves, would you swing again?

NETTER: Oh yeah, I feel I’m living out the dream of the little gay boy I once was. Traveling around getting a beat on different communities. If there’s a gay bar, I’m stopping by and meeting interesting and cool people.

BLADE: Speaking of that little gay boy, what drew him to theater?

NETTER: Grandma and mom were big movie musical fans, show likes “Singing in the Rain,” “Meet Me in St. Louis.” I have memories of my grandma dancing me around the house to “Shall We Dance?” from the “King and I” She put me in tap class at age four.

BLADE: What are your career highlights to date?

NETTER: Studying the Meisner techniqueat New York’sNeighborhood Playhouse for two years was definitely a highlight. Favorite parts would include the D’Ysquith family [all eight murder victims] in “A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder,” and the monstrous Miss Trunchbull in “Matilda.”

BLADE: And looking forward?

NETTER: I’d really like the chance to play Finch or Frump in Frank Loesser’s musical comedy “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.”

BLADE: In the meantime, you can find Netter backstage at the National waiting to hear those exhilarating words “You’re on!”