a&e features

The straight and narrow?

D.C.’s two largest LGBT choirs have straight directors

Thea Kano directs the Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington at the U.S. Supreme Court. (Washington Blade photo by Michael Key)

Jeff Herrell, a decade-plus member of Metropolitan Community Church of Washington, the region’s largest mostly LGBT church, was at the Fellowship’s general conference last year and as he sat listening to a pastor from Indianapolis, something he heard rubbed him the wrong way.

The crux of the argument was that if the Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches, a network of LGBT-welcoming churches started by Troy Perry in 1968 in the face of almost universal condemnation of gays by mainstream Christian churches, is to survive, it will need to engage straight believers as well.

It’s not a new concept. Many LGBT activists have stated the movement would have achieved far less traction over the past 40-odd years without ally aid. But for Herrell, a Washingtonian of 15 years and a gay believer, the statements inspired an internal groan.

“When I heard that, my first thought was, ‘Oh gosh, really?,’ he says. “It’s a challenge for me because MCC for me is like my personal gay sanctuary away from the straight world in a way.”

A pragmatist, though, Herrell also recognizes the world is changing.

“There is an element of it that’s a little sad, but you know what, we’re old,” he says with a laugh. “This is a post-‘Will & Grace’ world and it’s just not the same as it used to be. It’s like when all the straight girls started going to the gay clubs for their bachelorette parties, you know. I thought, ‘Jesus, I hate this, go somewhere else,’ but you know what? Here we are 10 years later.”

In August, the Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, a 34-year-old local choir that has about 240 active members and is one of the oldest and largest such groups in the country, announced Thea Kano as its new artistic director. She is the successor to Jeff Buhrman who was at the helm 13 years and involved with the Chorus for 25, and is the first straight director in the group’s history. Chase Maggiano, GMCW’s executive director, says her proven history with the group — she’d been its associate director since 2004 — was considered, but she was given no bonus points over the 30 applicants and four other finalists who applied during a seven-month national search.

“She went through every step of the process just like everyone else,” Maggiano says. “As soon as it was announced that Jeff was resigning, we started getting inquiries. … We figured she would apply but we were up front with her that we were going to take our time to make this a fair and open process so that whomever was ultimately appointed, was legit. We wanted a legitimate and fair process and that was my commitment to the process to kind of be the fairness czar.”

So thorough, in fact, was the process, it was a source of angst for some GMCW singers who’d grown to love Kano and feared she might resign if not given the job.

“We were really happy and really relieved when the news came out that she’d been appointed,” says Eric Peterson, a tenor who’s been in the Chorus five years and is also a member or the Rock Creek Singers, a smaller chamber ensemble within the overall Chorus that Kano has directed for a decade. “I don’t know if she might have stayed either way. She was very careful not to say, but she has a doctorate in choral conducting and has studied and worked with some of the most famous conductors in choral music so I can’t imagine she would have just stuck around indefinitely. … When the news came out, there was a huge sigh of relief and a lot of applause.”

Kano, who splits her time between Washington and the Big Apple directing the 80-voice New York City Master Chorale, says she’s thrilled.

“I’m like a kid in a candy store,” she says. “I really get the best of all worlds here.” She says there was “no yearning” for the chief role even when people started asking her if it was a goal after she’d been with the Chorus a couple years, though she also says when Buhrman announced he was stepping down, applying herself was “a no brainer.”

“Having been here so long, I have that institutional memory and I’ve seen how we’ve grown musically,” she says. “I recognize the things that have really worked and well the audience appreciated this or that. … My goal is to continue with a phenomenal musical product to drive home our overall message of equality.”

When the choir at MCC-D.C. met Michael Fisher Jr., who just started as the church’s “minister of worship arts,” they didn’t know his sexual orientation. The church for years had two choirs with as many as 40-50 singers in the combined group. It has dwindled some in recent years without a full-time director. Several former singers are now active with former director Shirli Hughes’ group Ovation.

Fisher is classically trained on the cello and piano and has worked with several well-known gospel acts. What struck them initially during an audition rehearsal, Herrell says, was his stellar musical ability.

“We just kind of assumed he probably was gay but we didn’t know,” Herrell says. “We had a rehearsal with him and it just went really, really well. He can play the piano like nobody’s business and he’s also just so vocally talented too. … He had a way of teaching that was very easy and he was able to make himself understood. Within like 15-20 minutes, he had us singing a song he’d taught us. It was a great experience and I think everyone was just excited to find someone that talented interested in the position because we have a history of a very strong music program here and it’s something we definitely want to uphold.”

As with the GMCW, the search committee, pastoral staff and board of directors at MCC-D.C., founded in 1970, took its time in the search. All the church’s former choir directors have been LGBT.

Justin Ritchie co-directed the MCC choir for several years with Darius Smith but neither were interested in doing the job full-time. In a series of evaluations, the congregation there — which Herrell guesses is “probably less than 1 percent straight” — wanted someone in this new position in a full-time capacity.

Rev. Cathy Alexander, MCC’s minister of congregational connections, says the process was exceedingly thorough and says she’s excited to see Fisher join the staff. (Fisher did not respond to multiple attempts to interview him before this week’s Blade deadline. He’s started his new post but will be officially welcomed at special services at 9 and 11 a.m. on Sept. 14. The church’s senior pastor, Rev. Dwayne Johnson, also did not respond to interview requests.)

“First and foremost, he’s a very spiritual man, very dedicated to serving God, that came through first and foremost,” Alexander, who identifies as gender non-conforming, says. “He has an amazing ability, he writes his own songs and travels and sings. … He’s very personable and has already established a good relationship with the choir and dance ministries. He grew up in the church playing music, he’s a good fit for this position and his wife is just lovely, too.”

But despite thorough searches and stellar musical qualifications, is there any long-term concern about having the city’s largest LGBT choirs — the Lesbian and Gay Chorus of Washington having folded in 2010 (former director C. Paul Heins is now the GMCW associate director) — under straight leadership?

While several say it is a bit unusual and perhaps a sign of the times, nobody the Blade interviewed said it’s an important distinction. Kano, especially, several GMCW members said, has never inspired any doubt about her commitment to LGBT rights.

Ritchie, who has sung for years with the GMCW in addition to his duties at MCC, concurs.

“Thea has great gay sensibility if you will and she’s a great programmer,” he says. “She’s an artist and the Chorus couldn’t be in better hands. I think it will be a seamless transition with her in charge.”

Ritchie, who has yet to meet Fisher, says the role at MCC is a wholly different situation. He says because the role requires someone who can both conduct and accompany and who is stylistically diverse, it was a hard position to fill.

“At 9, it’s more like high church, then at the 11 o’clock service it’s straight-up black gospel and there are not many people who can do it all. I kind of faked my way through it for a year and a half … but it’s such a varied position.”

The spiritual component only further complicates the matter, Ritchie says.

“Concerned is probably too strong of a word and it’s really not my business anymore, but I would want to be sure that whomever they might have hired for this position has the best of intentions,” he says. “Is it somebody who really feels called to this church or is it just somebody who needed a job? That would be understandable, but it would be my hope that they would make sure it’s not somebody who’s coming in to convert anybody. It’s just so hard to fully understand the gay faith community in the context of past hurt or past injury if you haven’t experienced it that way. … There has to be not only the musicality, but also the safety and the celebration of who LGBTQ people are.”

Neither appointment is an anomaly, as far as anybody can tell. Other choruses within the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses (GALA) have had straight directors, although it is certainly not the norm.

Robin Godfrey, GALA’s executive director and a lesbian, says she’s known of some straight conductors but says she’s not given much thought to how widespread the phenomenon might be.

“It’s certainly not the sort of thing we would ask,” she says. “In some cases, there may be straight conductors you may know of, but how many, I really don’t know.”

Rev. Kharma Amos, associate director of formation and leadership development for Metropolitan Community Churches and a Fairfax, Va., resident and lesbian, says she has no idea how many of the Fellowship’s 200-plus congregations around the world might have straight music ministers. She says a “wild guess” might be that “30 or 40” MCC churches in the U.S. are large enough to have full-time music staff. All candidates for ordination in the Fellowship go through classes she helps lead and she says about two of the 15 who come through each year identify as straight.

“It’s hard to generalize as to the whys, but often they’ve identified the inclusivity MCC exhibits as being extraordinary compared to other denominations and they felt a calling to social justice issues,” Amos says.

Ritchie says he knows of several paid musicians at MCC churches in Minneapolis and Ft. Lauderdale who are straight though he says, “the vast majority are LGBT.”

Kano, who grew up in the San Francisco area, knew many gay dancers studying ballet growing up and says “it was just never an issue.” She eventually came to consider herself an LGBT activist and says upon finishing graduate school at UCLA and applying to conducting jobs “all over,” a friend in Los Angeles heard GMCW had an open position 10 years ago.

“My first thought was, ‘Why would they want me,’ but he said, ‘Well, you’re a gay activist and always have been,’ so I sent in my resume and fast forward, here we are. That’s how it came to be on my radar,” she says.

Nobody the Blade spoke to said the appointments raised any eyebrows within the two choirs.

“When DOMA was struck down, she was the one who was there singing with us at the Supreme Court all day,” Peterson says. “She was wiping tears and it wasn’t just for us, it was for the entire movement. … She’s such an ally, I really do consider her part of the LGBT umbrella. I don’t think of many straight people in my life that way, but she is an exception.”

Herrell, too, says he “didn’t hear anybody say anything” about Fisher and potential concerns.

If anything, Herrell says it would have been hypocritical for MCC to have not considered a straight candidate considering the church’s mantra toward being open and welcoming to all.

“There’s really no valid reason why a heterosexual can’t be the music director for a gay church especially when the message we’re hearing from the pulpit every Sunday is one of radical inclusiveness. … I can honestly say, there was nobody who was like, ‘Hold on, let’s slow down here,’ — nothing like that was said that I know of.”

Although most would agree that’s the politically correct answer, is it any different when an organization’s entire raison d’être is LGBT based? As Whitman-Walker Health has broadened its scope in recent years and has a straight executive director (Don Blanchon), will this phenomenon spill over into our traditionally gay churches and arts organizations? Some national gay rights groups, like the National Black Justice Coalition, have directors who are straight allies. And Washington’s LGBT amateur sports teams are reporting higher levels of straight participation than ever before, Team D.C. officials say. Lines everywhere seem to be blurring as the gay rights movement gains increased footing.

Gay directors applied for both jobs but those involved in the searches said when all factors were considered, Kano and Fisher were the best fits.

“Of the five finalists, I can say yes, some of them were gay,” Maggiano says. “But we really didn’t have a cut-and-dried scenario where all other factors were equal and we had to decide on that. We did not discriminate on gender, religion, sexual orientation or anything else. … We just didn’t find ourselves in a situation where it was a gay versus a non-gay issue.”

But what does it mean? Is it coincidence? A sign of the changing times? The first steps in the what could be a gradual “de-gaying” of our traditional LGBT safe spaces? As a point of context, Dignity Washington, a local LGBT Catholic group, has had a straight choir director for years. Members say it’s never been an issue. She’s low key, though, and asked that her name not be used as she also directs music in local Roman Catholic parishes and doesn’t want to risk drawing the ire of anti-gay church leaders, a threat organist and choir director Mike McMahon of National City Christian Church knows is very real. He lost his job at St. Agnes Catholic Church in Arlington after he married his male partner earlier this year.

He says there are many factors at play with the new choir directors, but says it ultimately shouldn’t be an issue.

“What we’re seeing is the results of the mainstreaming of gay culture,” McMahon says. “It’s a thing that cuts both ways. Once it’s OK for gay people to have a certain job, then it’s OK for straight people to have these more traditionally gay jobs as well. With (Kano) especially, the issue is not that she’s straight or that she’s a woman. She’s been immersed in that environment for so many years and has shown that she has the chops to make those guys sound amazing. I think it’s great.”

Anthony Heilbut knows what it’s like to be considered an outsider. He’s a self-described Jewish atheist but as a life-long lover of black gospel music who eventually came to be considered an expert on the subject as a producer of many traditional gospel acts and author of “The Gospel Sound” and “The Fan Who Knew Too Much.”

Heilbut says many may not realize the long tradition “children,” historically the term black Christians used for the low-key gays and lesbians in their ranks, have of being choir directors.

“In gospel music, the greatest choir directors have almost universally been gay men,” Heilbut, who’s gay, says. “This situation here in D.C. strikes me as just a curiosity and a fascinating situation because it really should not be hard to find a gay choir director of all things. … This is just one area in which gay men have always excelled, going all the way back to James Cleveland and before.”

Maggiano says GMCW is “actually ramping up our gayness.”

“I know it might sound strange considering we just hired a straight female, but what we’re really doing is inviting people to come be gay with us. Let your hair down. Put on a wig. In this market, it’s cool to be gay. … We would actually love it if in 10 years we had half gay men and half straight singing ‘YMCA.’ How great would it be to see some straight guy just wailing on Beyonce? What a great place we would have come to and what a great statement that we got here through music. … That’s our goal. Not to stay internal and stay exclusively gay, but to make gay cool for everybody.”

Godfrey puts it more succinctly.

“There’s no reason it has to be an issue,” she says.

The choir at Metropolitan Community Church of Washington in 2008. (Washington Blade file photo by Henry Linser)

a&e features

Visit Cambridge, a ‘beautiful secret’ on Maryland’s Eastern Shore

New organization promotes town’s welcoming vibe, LGBTQ inclusion

CAMBRIDGE, Md. — Driving through this scenic, historic town on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, you’ll be charmed by streets lined with unique shops, restaurants, and beautifully restored Victorian homes. You’ll also be struck by the number of LGBTQ Pride flags flying throughout the town.

The flags are a reassuring signal that everyone is welcome here, despite the town’s location in ruby red Dorchester County, which voted for Donald Trump over Kamala Harris by a lopsided margin. But don’t let that deter you from visiting. A new organization, Proudly Cambridge, is holding its debut Pride event this weekend, touting the town’s welcoming, inclusive culture.

“We stumbled on a beautiful secret and we wanted to help get the word out,” said James Lumalcuri of the effort to create Proudly Cambridge.

The organization celebrates diversity, enhances public spaces, and seeks to uplift all that Cambridge has to share, according to its mission statement, under the tagline “You Belong Here.”

The group has so far held informal movie nights and a picnic and garden party; the launch party is June 28 at the Cambridge Yacht Club, which will feature a Pride celebration and tea dance. The event’s 75 tickets sold out quickly and proceeds benefit DoCo Pride.

“Tickets went faster than we imagined and we’re bummed we can’t welcome everyone who wanted to come,” Lumalcuri said, adding that organizers plan to make “Cheers on the Choptank” an annual event with added capacity next year.

One of the group’s first projects was to distribute free Pride flags to anyone who requested one and the result is a visually striking display of a large number of flags flying all over town. Up next: Proudly Cambridge plans to roll out a program offering affirming businesses rainbow crab stickers to show their inclusiveness and LGBTQ support. The group also wants to engage with potential visitors and homebuyers.

“We want to spread the word outside of Cambridge — in D.C. and Baltimore — who don’t know about Cambridge,” Lumalcuri said. “We want them to come and know we are a safe haven. You can exist here and feel comfortable and supported by neighbors in a way that we didn’t anticipate when we moved here.”

Lumalcuri, 53, a federal government employee, and his husband, Lou Cardenas, 62, a Realtor, purchased a Victorian house in Cambridge in 2021 and embarked on an extensive renovation. The couple also owns a home in Adams Morgan in D.C.

“We saw the opportunity here and wanted to share it with others,” Cardenas said. “There’s lots of housing inventory in the $300-400,000 range … we’re not here to gentrify people out of town because a lot of these homes are just empty and need to be fixed up and we’re happy to be a part of that.”

Lumalcuri was talking with friends one Sunday last year at the gazebo (affectionately known as the “gayzebo” by locals) at the Yacht Club and the idea for Proudly Cambridge was born. The founding board members are Lumalcuri, Corey van Vlymen, Brian Orjuela, Lauren Mross, and Caleb Holland. The group is currently working toward forming a 501(c)3.

“We need visibility and support for those who need it,” Mross said. “We started making lists of what we wanted to do and the five of us ran with it. We started meeting weekly and solidified what we wanted to do.”

Mross, 50, a brand strategist and web designer, moved to Cambridge from Atlanta with her wife three years ago. They knew they wanted to be near the water and farther north and began researching their options when they discovered Cambridge.

“I had not heard of Cambridge but the location seemed perfect,” she said. “I pointed on a map and said this is where we’re going to move.”

The couple packed up, bought a camper trailer and parked it in different campsites but kept coming back to Cambridge.

“I didn’t know how right it was until we moved here,” she said. “It’s the most welcoming place … there’s an energy vortex here – how did so many cool, progressive people end up in one place?”

Corey van Vlymen and his husband live in D.C. and were looking for a second home. They considered Lost River, W.Va., but decided they preferred to be on the water.

“We looked at a map on both sides of the bay and came to Cambridge on a Saturday and bought a house that day,” said van Vlymen, 39, a senior scientist at Booz Allen Hamilton. They’ve owned in Cambridge for two years.

They were drawn to Cambridge due to its location on the water, the affordable housing inventory, and its proximity to D.C.; it’s about an hour and 20 minutes away.

Now, through the work of Proudly Cambridge, they hope to highlight the town’s many attributes to residents and visitors alike.

“Something we all agree on is there’s a perception problem for Cambridge and a lack of awareness,” van Vlymen said. “If you tell someone you’re going to Cambridge, chances are they think, ‘England or Massachusetts?’”

He cited the affordability and the opportunity to save older, historic homes as a big draw for buyers.

“It’s all about celebrating all the things that make Cambridge great,” Mross added. “Our monthly social events are joyful and celebratory.” A recent game night drew about 70 people.

She noted that the goal is not to gentrify the town and push longtime residents out, but to uplift all the people who are already there while welcoming new visitors and future residents.

They also noted that Proudly Cambridge does not seek to supplant existing Pride-focused organizations. Dorchester County Pride organizes countywide Pride events and Delmarva Pride was held in nearby Easton two weeks ago.

“We celebrate all diversity but are gay powered and gay led,” Mross noted.

To learn more about Proudly Cambridge, visit the group on Facebook and Instagram.

What to see and do

Cambridge, located 13 miles up the Choptank River from the Chesapeake Bay, has a population of roughly 15,000. It was settled in 1684 and named for the English university town in 1686. It is home to the Harriet Tubman Museum, mural, and monument. Its proximity to the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge makes it a popular stop for birders, drawn to more than 27,000 acres of marshland dubbed “the Everglades of the north.”

The refuge is walkable, bikeable, and driveable, making it an accessible attraction for all. There are kayaking and biking tours through Blackwater Adventures (blackwateradventuresmd.com).

Back in town, take a stroll along the water and through historic downtown and admire the architecture. Take in the striking Harriet Tubman mural (424 Race St.). Shop in the many local boutiques, and don’t miss the gay-owned Shorelife Home and Gifts (421 Race St.), filled with stylish coastal décor items.

Stop for breakfast or lunch at Black Water Bakery (429 Race St.), which offers a full compliment of coffee drinks along with a build-your-own mimosa bar and a full menu of creative cocktails.

The Cambridge Yacht Club (1 Mill St.) is always bustling but you need to be a member to get in. Snapper’s on the water is temporarily closed for renovations. RaR Brewing (rarbrewing.com) is popular for craft beers served in an 80-year-old former pool hall and bowling alley. The menu offers burgers, wings, and other bar fare.

For dinner or wine, don’t miss the fantastic Vintage 414 (414 Race St.), which offers lunch, dinner, wine tasting events, specialty foods, and a large selection of wines. The homemade cheddar crackers, inventive flatbreads, and creative desserts (citrus olive oil cake, carrot cake trifle) were a hit on a recent visit.

Also nearby is Ava’s (305 High St.), a regional chain offering outstanding Italian dishes, pizzas, and more.

For something off the beaten path, visit Emily’s Produce (22143 Church Creek Rd.) for its nursery, produce, and prepared meals.

“Ten minutes into the sticks there’s a place called Emily’s Produce, where you can pay $5 and walk through a field and pick sunflowers, blueberries, you can feed the goats … and they have great food,” van Vlymen said.

As for accommodations, there’s the Hyatt Regency Chesapeake Bay (100 Heron Blvd. at Route 50), a resort complex with golf course, spa, and marina. Otherwise, check out Airbnb and VRBO for short-term rentals closer to downtown.

Its proximity to D.C. and Baltimore makes Cambridge an ideal weekend getaway. The large LGBTQ population is welcoming and they are happy to talk up their town and show you around.

“There’s a closeness among the neighbors that I wasn’t feeling in D.C.,” Lumalcuri said. “We look after each other.”

a&e features

James Baldwin bio shows how much of his life is revealed in his work

‘A Love Story’ is first major book on acclaimed author’s life in 30 years

‘Baldwin: A Love Story’

By Nicholas Boggs

c.2025, FSG

$35/704 pages

“Baldwin: A Love Story” is a sympathetic biography, the first major one in 30 years, of acclaimed Black gay writer James Baldwin. Drawing on Baldwin’s fiction, essays, and letters, Nicolas Boggs, a white writer who rediscovered and co-edited a new edition of a long-lost Baldwin book, explores Baldwin’s life and work through focusing on his lovers, mentors, and inspirations.

The book begins with a quick look at Baldwin’s childhood in Harlem, and his difficult relationship with his religious, angry stepfather. Baldwin’s experience with Orilla Miller, a white teacher who encouraged the boy’s writing and took him to plays and movies, even against his father’s wishes, helped shape his life and tempered his feelings toward white people. When Baldwin later joined a church and became a child preacher, though, he felt conflicted between academic success and religious demands, even denouncing Miller at one point. In a fascinating late essay, Baldwin also described his teenage sexual relationship with a mobster, who showed him off in public.

Baldwin’s romantic life was complicated, as he preferred men who were not outwardly gay. Indeed, many would marry women and have children while also involved with Baldwin. Still, they would often remain friends and enabled Baldwin’s work. Lucien Happersberger, who met Baldwin while both were living in Paris, sent him to a Swiss village, where he wrote his first novel, “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” as well as an essay, “Stranger in the Village,” about the oddness of being the first Black person many villagers had ever seen. Baldwin met Turkish actor Engin Cezzar in New York at the Actors’ Studio; Baldwin later spent time in Istanbul with Cezzar and his wife, finishing “Another Country” and directing a controversial play about Turkish prisoners that depicted sexuality and gender.

Baldwin collaborated with French artist Yoran Cazac on a children’s book, which later vanished. Boggs writes of his excitement about coming across this book while a student at Yale and how he later interviewed Cazac and his wife while also republishing the book. Baldwin also had many tumultuous sexual relationships with young men whom he tried to mentor and shape, most of which led to drama and despair.

The book carefully examines Baldwin’s development as a writer. “Go Tell It on the Mountain” draws heavily on his early life, giving subtle signs of the main character John’s sexuality, while “Giovanni’s Room” bravely and openly shows a homosexual relationship, highly controversial at the time. “If Beale Street Could Talk” features a woman as its main character and narrator, the first time Baldwin wrote fully through a woman’s perspective. His essays feel deeply personal, even if they do not reveal everything; Lucian is the unnamed visiting friend in one who the police briefly detained along with Baldwin. He found New York too distracting to write, spending his time there with friends and family or on business. He was close friends with modernist painter Beauford Delaney, also gay, who helped Baldwin see that a Black man could thrive as an artist. Delaney would later move to France, staying near Baldwin’s home.

An epilogue has Boggs writing about encountering Baldwin’s work as one of the few white students in a majority-Black school. It helpfully reminds us that Baldwin connects to all who feel different, no matter their race, sexuality, gender, or class. A well-written, easy-flowing biography, with many excerpts from Baldwin’s writing, it shows how much of his life is revealed in his work. Let’s hope it encourages reading the work, either again or for the first time.

a&e features

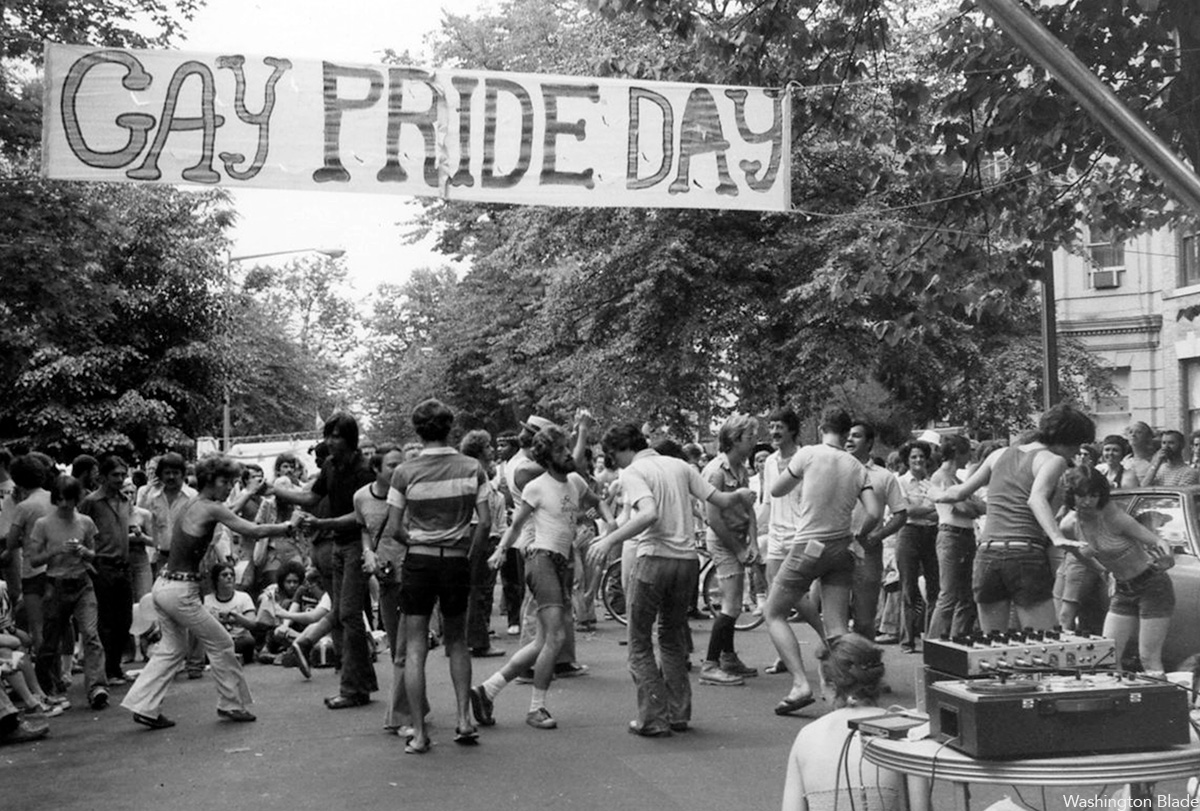

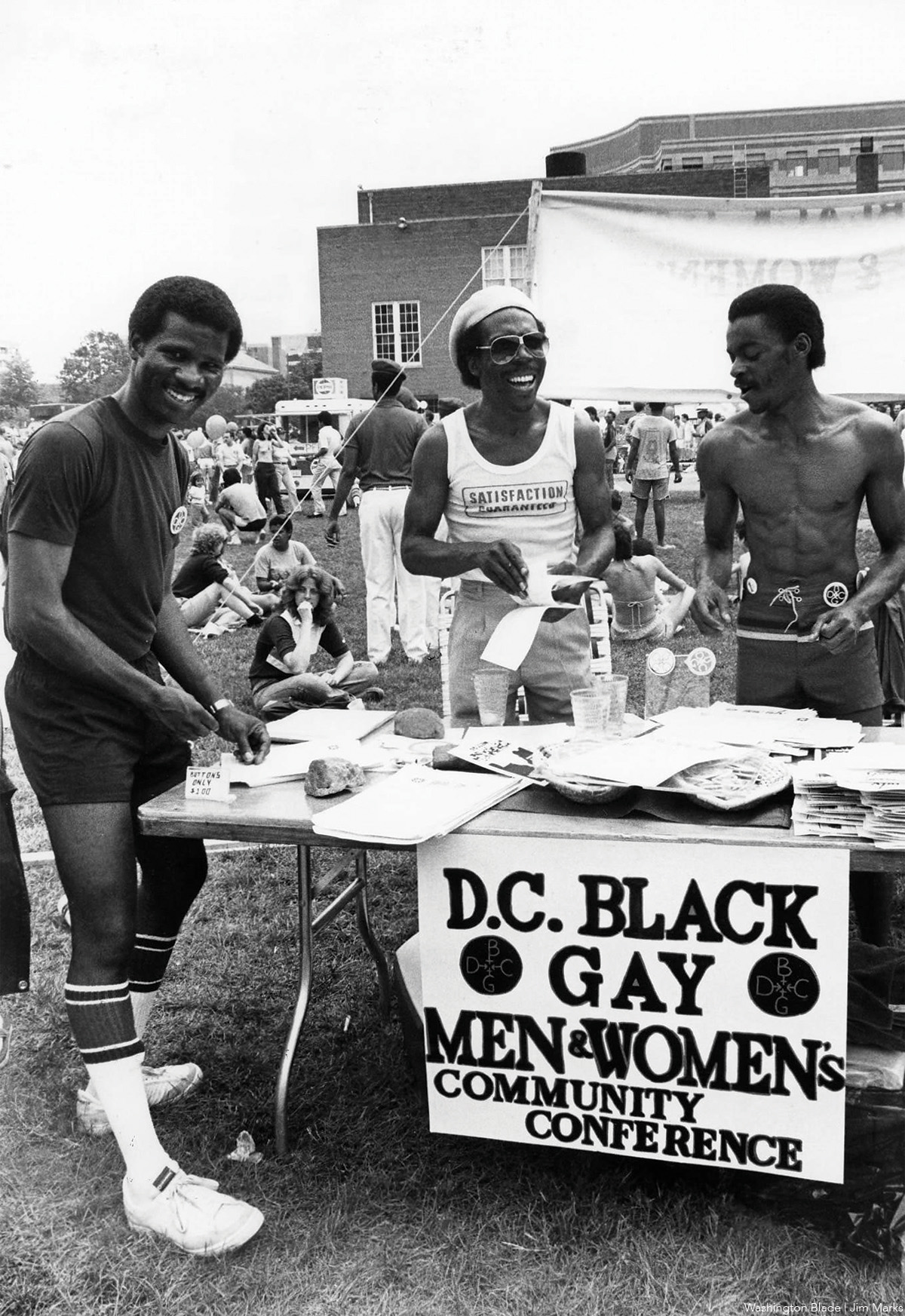

Looking back at 50 years of Pride in D.C

Washington Blade’s unique archives chronicle highs, lows of our movement

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of LGBTQ Pride in Washington, D.C., the Washington Blade team combed our archives and put together a glossy magazine showcasing five decades of celebrations in the city. Below is a sampling of images from the magazine but be sure to find a print copy starting this week.

The magazine is being distributed now and is complimentary. You can find copies at LGBTQ bars and restaurants across the city. Or visit the Blade booth at the Pride festival on June 7 and 8 where we will distribute copies.

Thank you to our advertisers and sponsors, whose support has enabled us to distribute the magazine free of charge. And thanks to our dedicated team at the Blade, especially Photo Editor Michael Key, who spent many hours searching the archives for the best images, many of which are unique to the Blade and cannot be found elsewhere. And thanks to our dynamic production team of Meaghan Juba, who designed the magazine, and Phil Rockstroh who managed the process. Stephen Rutgers and Brian Pitts handled sales and marketing and staff writers Lou Chibbaro Jr., Christopher Kane, Michael K. Lavers, Joe Reberkenny along with freelancer and former Blade staffer Joey DiGuglielmo wrote the essays.

The magazine represents more than 50 years of hard work by countless reporters, editors, advertising sales reps, photographers, and other media professionals who have brought you the Washington Blade since 1969.

We hope you enjoy the magazine and keep it as a reminder of all the many ups and downs our local LGBTQ community has experienced over the past 50 years.

I hope you will consider supporting our vital mission by becoming a Blade member today. At a time when reliable, accurate LGBTQ news is more essential than ever, your contribution helps make it possible. With a monthly gift starting at just $7, you’ll ensure that the Blade remains a trusted, free resource for the community — now and for years to come. Click here to help fund LGBTQ journalism.

-

U.S. Supreme Court3 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court3 days agoSupreme Court upholds ACA rule that makes PrEP, other preventative care free

-

U.S. Supreme Court3 days ago

U.S. Supreme Court3 days agoSupreme Court rules parents must have option to opt children out of LGBTQ-specific lessons

-

India5 days ago

India5 days agoIndian court rules a transgender woman is a woman

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoEvan Wolfson on the 10-year legacy of marriage equality