Arts & Entertainment

Ahead of their time

New book explores how 20th century writers put gay issues on America’s radar

Gay writer Christopher Bram knew in researching his new book, which involved excavating ancient reviews of the work of prominent queer authors of the mid-20th century and beyond, he’d find ugly instances where homophobia colored the various assessments — he just didn’t realize how unrelenting and vitriolic it would be.

“I just wasn’t prepared for how mean and ugly and vicious the reviews could be of anything gay from the ‘50s well into the ‘80s,” Bram says during a phone chat from San Francisco. “The amount of anti-gay feeling among literary straight people just floored me. Even from people who were more on our side, the amount of condescension and this sneering, snickering tone, it got quite tiring and I only ended up quoting about half of what I found.”

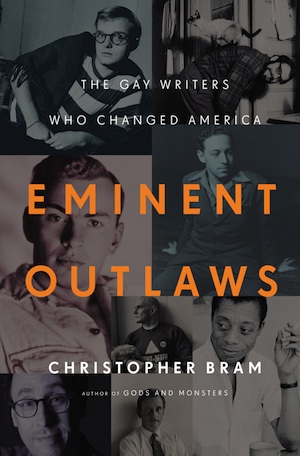

The book, out this month, is “Eminent Outlaws: the Gay Writers Who Changed America” (Twelve Books, $27.99). Bram’s premise is that the work of mid-century gay writers such as Truman Capote, Gore Vidal, James Baldwin, Allen Ginsberg, Tennessee Williams and others, on through to later novelists and playwrights such as Christopher Isherwood, Edward Albee, Edmund White, Armistead Maupin, Mart Crowley and Tony Kushner, was a literary revolution that laid the post-World War II groundwork for the modern gay rights movement. Bram, author of “The Father of Frankenstein” (adapted for the screen as the Oscar-winning film “Gods and Monsters”) and eight other novels, says the writers he includes in the book “introduced America to gay experience and sensibility and changed our literary culture.”

It’s a weighty thesis that unleashes an ocean of questions, some covered in the book, others pitched at Bram during this week’s Blade interview. And with Oscar season upon us (they’ll be handed out in Los Angeles Sunday evening), it’s an especially timely moment to consider the seemingly disproportionate contributions of gay writers to the arts. Nearly all the writers he covers have had work adapted to the big screen so their cultural reach is far-ranging and every bit as considerable as their straight counterparts.

Bram was a fan of these writers for decades. About three years ago he was approached by another writer, Sam Wasson, who was researching a book about the film “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (based on a Capote novel), and contacted Bram for literary context. After riffing on the state of gay life and gay writing in the ‘50s and thereafter in the U.S., it occurred to Bram that while nearly all of the writers he focuses on had been written about, there was no single book that explored how their lives and work — many of them knew each other — overlapped and fit into the cultural norms of the day while also influencing those norms often in shocking ways.

While much of the historical material in the book has been presented elsewhere — Bram says only a few points required fresh interviews — the overall story, he says, is not widely known but should be.

“There were all these little bits and pieces like this scattered jigsaw puzzle, but I really wanted to pull them all together to form one big picture,” he says. “What I did was connect the dots. Nobody had ever told this as a single narrative. There were some simple connections I was able to make, even something as simple and obvious as the fact that ‘Other Voices, Other Rooms’ (a gay-themed Capote book), ‘The City and the Pillar’ (from rival Gore Vidal) and the Kinsey Report all came out within a few weeks of each other in 1948, which is surprisingly early and yet it became really this powerhouse year where these gay books were suddenly getting all this attention.”

Bram says it was a uniquely American phenomenon the catalyst of which was the way World War II had “suddenly brought all these people together in the Army, the Navy — they were exposed to this other type of sexuality, to bad language and profanity they’d never heard before and it didn’t take long for this to be reflected in the publishing industry.”

The book is setting gay tongues wagging and even those who’ve yet to read it, say Bram’s premise is intriguing.

Nicholas Benton, a local gay writer and founder/publisher of the Falls-Church News Press who’s written at length about the unique contributions of gays in culture and society, says that although he takes issue with some of Bram’s contextualization and assessments of some of his subject’s supposed lesser works — Benton’s about halfway through “Outlaws” — he calls it “a very important book with a lot of important information in it.”

So did these writers’ homosexuality and perhaps the outsider status it brought it with it make their work greater than it otherwise might have been?

“One of the features of being a gay person is you can’t help but have an alternate perspective on life,” Benton says. “A straight man walks in the room, sees the hot secretary and that’s all he can think about. A gay man comes in and notices the drapes clash with the rug. I mean obviously that’s an oversimplification, but gay sensibility has something to do with seeing the plight of people who are often invisible to the mind of a straight person … we bring an alternate perspective.”

Bram has a slightly different take. He says, “One would like to think (being gay) would create more empathy but maybe what we can say about homosexuality is much like what we say about religion — it makes the good people better and the bad people worse … for gays, that could mean being overly bitchy, negative or hypercritical of others or full of self pity that doesn’t turn to empathy, it could affect them in many different ways.”

Others say these writers helped America shed some of its Puritanical squeamishness toward sex and “grow up.” Ginsberg’s poem “Howl,” especially, is shockingly bold for its time. It’s amazing it got published in 1955.

“In the case of Williams, he was inestimable in helping to hammer the nails in movie censorship in post-war America,” says Drew Casper, a film expert and professor of critical studies at the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California. “Whether his adaptations came through strong or diluted, no mistaking his championing the importance of sex in the lives of his characters, often as a way for them to touch God. Sexuality is an important concern in gay life and relationships, so when gay writers take pen in hand, sexuality is a concern.”

Gay author William J. Mann, who has a bounty of novels and non-fiction Hollywood-themed books to his credit, says he’s “a huge fan” of Bram and “can’t wait” to read “Outlaws.” Mann calls the topic “fascinating” and “great.”

“The role of the arts is always to push what’s expected or what’s understood and certainly when you read the works of James Baldwin for example … you have this real sense of ground being broken and getting people to really understand the wider experience of humanity in a way that the world is much more than just your own little sphere of existence,” Mann says.

Bram says the writers he covers deserve enormous credit — whether it’s Vidal’s cheeky handling of transsexuality in “Myra Breckenridge” or Kushner’s sophisticated handling of the AIDS crisis in “Angels in America” — for getting gay topics on the cultural radar.

“They got the stories out there,” he says. “Homosexuality became a subject that straight and gay people could finally talk about and once people were talking about it, other people started talking about it too. It’s an example of where art did a better job than activism. ‘Boys in the Band’ was made into a movie in 1970 and it played in every major city in the country with prominent actors just a year after the Stonewall riots. In my group of friends at the time, none of us had heard of the Stonewall riots, but we’d all heard of ‘Boys in the Band.’”

The 44th annual Queen of Hearts pageant was held at The Lodge in Boonsboro, Md. on Friday, Feb. 20. Six contestants vied for the title and Bev was crowned the winner.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

View on Threads

Books

New book profiles LGBTQ Ukrainians, documents war experiences

Tuesday marks four years since Russia attacked Ukraine

Journalist J. Lester Feder’s new book profiles LGBTQ Ukrainians and their experiences during Russia’s war against their country.

Feder for “The Queer Face of War: Portraits and Stories from Ukraine” interviewed and photographed LGBTQ Ukrainians in Kyiv, the country’s capital, and in other cities. They include Olena Hloba, the co-founder of Tergo, a support group for parents and friends of LGBTQ Ukrainians, who fled her home in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha shortly after Russia launched its war on Feb. 24, 2022.

Russian soldiers killed civilians as they withdrew from Bucha. Videos and photographs that emerged from the Kyiv suburb showed dead bodies with their hands tied behind their back and other signs of torture.

Olena Shevchenko, chair of Insight, a Ukrainian LGBTQ rights group, wrote the book’s forward.

The book also profiles Viktor Pylypenko, a gay man who the Ukrainian military assigned to the 72nd Mechanized Black Cossack Brigade after the war began. Feder writes Pylypenko’s unit “was deployed to some of the fiercest and most important battles of the war.”

“The brigade was pivotal to beating Russian forces back from Kyiv in their initial attempt to take the capital, helping them liberate territory near Kharkiv and defending the front lines in Donbas,” wrote Feder.

Pylypenko spent two years fighting “on Ukraine’s most dangerous battlefields, serving primarily as a medic.”

“At times he felt he was living in a horror movie, watching tank shells tear his fellow soldiers apart before his eyes,” wrote Feder. “He held many men as they took their final breaths. Of the roughly one hundred who entered the unit with him, only six remained when he was discharged in 2024. He didn’t leave by choice: he went home to take care of his father, who had suffered a stroke.”

Feder notes one of Pylypenko’s former commanders attacked him online when he came out. Pylypenko said another commander defended him.

Feder also profiled Diana and Oleksii Polukhin, two residents of Kherson, a port city in southern Ukraine that is near the mouth of the Dnieper River.

Ukrainian forces regained control of Kherson in November 2022, nine months after Russia occupied it.

Diana, a cigarette vender, and Polukhin told Feder that Russian forces demanded they disclose the names of other LGBTQ Ukrainians in Kherson. Russian forces also tortured Diana and Polukhin while in their custody.

Polukhim is the first LGBTQ victim of Russian persecution to report their case to Ukrainian prosecutors.

Feder, who is of Ukrainian descent, first visited Ukraine in 2013 when he wrote for BuzzFeed.

He was Outright International’s Senior Fellow for Emergency Research from 2021-2023. Feder last traveled to Ukraine in December 2024.

Feder spoke about his book at Politics and Prose at the Wharf in Southwest D.C. on Feb. 6. The Washington Blade spoke with Feder on Feb. 20.

Feder told the Blade he began to work on the book when he was at Outright International and working with humanitarian groups on how to better serve LGBTQ Ukrainians. Feder said military service requirements, a lack of access to hormone therapy and documents that accurately reflect a person’s gender identity and LGBTQ-friendly shelters are among the myriad challenges that LGBTQ Ukrainians have faced since the war began.

“All of these were components of a queer experience of war that was not well documented, and we had never seen in one place, especially with photos,” he told the Blade. “I felt really called to do that, not only because of what was happening in Ukraine, but also as a way to bring to the surface issues that we’d had seen in Iraq and Syria and Afghanistan.”

Feder also spoke with the Blade about the war’s geopolitical implications.

Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2013 signed a law that bans the “promotion of homosexuality” to minors.

The 2014 Winter Olympics took place in Sochi, a Russian resort city on the Black Sea. Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine a few weeks after the games ended.

Russia’s anti-LGBTQ crackdown has continued over the last decade.

The Russian Supreme Court in 2023 ruled the “international LGBT movement” is an extremist organization and banned it. The Russian Justice Ministry last month designated ILGA World, a global LGBTQ and intersex rights group, as an “undesirable” organization.

Ukraine, meanwhile, has sought to align itself with Europe.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy after a 2021 meeting with then-President Joe Biden at the White House said his country would continue to fight discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. (Zelenskyy’s relationship with the U.S. has grown more tense since the Trump-Vance administration took office.) Zelenskyy in 2022 publicly backed civil partnerships for same-sex couples.

Then-Ukrainian Ambassador to the U.S. Oksana Markarova in 2023 applauded Kyiv Pride and other LGBTQ and intersex rights groups in her country when she spoke at a photo exhibit at Ukraine House in D.C. that highlighted LGBTQ and intersex soldiers. Then-Kyiv Pride Executive Director Lenny Emson, who Feder profiles in his book, was among those who attended the event.

“Thank you for everything you do in Kyiv, and thank you for everything that you do in order to fight the discrimination that still is somewhere in Ukraine,” said Markarova. “Not everything is perfect yet, but you know, I think we are moving in the right direction. And we together will not only fight the external enemy, but also will see equality.”

Feder in response to the Blade’s question about why he decided to write his book said he “didn’t feel” the “significance of Russia’s war against Ukraine” for LGBTQ people around the world “was fully understood.”

“This was an opportunity to tell that big story,” he said.

“The crackdown on LGBT rights inside Russia was essentially a laboratory for a strategy of attacking democratic values by attacking queer rights and it was one as Ukraine was getting closet to Europe back in 2013, 2014,” he added. “It was a strategy they were using as part of their foreign policy, and it was one they were using not only in Ukraine over the past decade, but around the world.”

Feder said Republicans are using “that same strategy to attack queer people, to attack democracy itself.”

“I felt like it was important that Americans understand that history,” he said.

More than a dozen LGBTQ athletes won medals at the Milan Cortina Winter Olympics that ended on Sunday.

Cayla Barnes, Hilary Knight, and Alex Carpenter are LGBTQ members of the U.S. women’s hockey team that won a gold medal after they defeated Canada in overtime. Knight the day before the Feb. 19 match proposed to her girlfriend, Brittany Bowe, an Olympic speed skater.

French ice dancer Guillaume Cizeron, who is gay, and his partner Laurence Fournier Beaudry won gold. American alpine skier Breezy Johnson, who is bisexual, won gold in the women’s downhill. Amber Glenn, who identifies as bisexual and pansexual, was part of the American figure skating team that won gold in the team event.

Swiss freestyle skier Mathilde Gremaud, who is in a relationship with Vali Höll, an Austrian mountain biker, won gold in women’s freeski slopestyle.

Bruce Mouat, who is the captain of the British curling team that won a silver medal, is gay. Six members of the Canadian women’s hockey team — Emily Clark, Erin Ambrose, Emerance Maschmeyer, Brianne Jenner, Laura Stacey, and Marie-Philip Poulin — that won silver are LGBTQ.

Swedish freestyle skier Sandra Naeslund, who is a lesbian, won a bronze medal in ski cross.

Belgian speed skater Tineke den Dulk, who is bisexual, was part of her country’s mixed 2000-meter relay that won bronze. Canadian ice dancer Paul Poirier, who is gay, and his partner, Piper Gilles, won bronze.

Laura Zimmermann, who is queer, is a member of the Swiss women’s hockey team that won bronze when they defeated Sweden.

Outsports.com notes all of the LGBTQ Olympians who competed at the games and who medaled.