National

UPDATED: Nation’s largest LGBT funder changing its focus?

Advocates worry ‘ATM is closed’ at Arcus Foundation

The Arcus Foundation, founded by billionaire philanthropist Jon Stryker, is the top LGBT-specific funder of grants, giving away $58.4 million to LGBT causes from 2007-2010.

UPDATE: We learned Friday after publishing this story that Arcus founder Jon Stryker had committed $200,000 to the campaign against North Carolina’s Amendment One late last week.

While most LGBT people have probably never heard of the Arcus Foundation, it has touched many of their lives.

The nation’s largest grant-maker to LGBT causes, Arcus delivers money to a range of non-profit groups advocating for LGBT rights and health.

But recent changes at Arcus have some advocates quietly worrying about the future of those programs.

Arcus CEO Yvette Burton departed April 3 amid rumors she was fired by the board. Burton, a former market development research director at IBM, took the helm of Arcus in January 2011 not long after the departure of longtime activist Urvashi Vaid, who spent five years running the foundation.

“Yvette’s departure was a termination,” said a source with knowledge of the situation at Arcus who spoke on condition of anonymity. The source added that Burton’s efforts to “clean house” at Arcus ruffled feathers throughout the organization.

Burton did not respond to several requests for comment.

An Arcus official told the Blade that the foundation’s work continues but the organization would not comment specifically on Burton’s departure.

“The Foundation’s commitment to its mission is longstanding,” Bryan Simmons, vice president of communications at Arcus, told the Blade. “Our strategies will continue to support that mission regardless of any change in leadership.”

Other changes at Arcus were evident before Burton’s departure. The organization’s board of directors had purportedly initiated a new strategic planning process to reassess programming and giving priorities, according to the source. Many organizations were reportedly told that they would not be guaranteed funding beyond 2012, and some ties were severed altogether.

“‘You’ll have to qualify under our new guidelines,’” the source paraphrased the message from Arcus to some of its LGBT grant recipients. “Subtext: ‘You’ll probably not be getting funding moving forward.’”

In addition, several sources also contend the organization’s founder, billionaire philanthropist Jon Stryker, may have ceased personally giving to political campaigns and 501(c)4 organizations, however after this article was originally published, the organizers of the campaign to stop Amendment One in North Carolina revealed that Stryker had wired the campaign $200,000 Friday. Stryker could not be reached for comment.

“Is this a prep to exit the LGBT space altogether? Possibly,” the source said. “Was [Burton] a disaster? Possibly.”

Another knowledgeable source noted the turnover at Arcus’ main office in Kalamazoo, Mich., and said that Stryker has had a change of heart regarding his philanthropic priorities.

Some activists unaffiliated with grantee organizations have attempted to sound the alarm.

“Any change at any funder in the LGBT movement is pretty big for any orgs they fund,” said Kalpana Krishnamurphy, director of the Race and Gender Justice Program at the Western States Center, an immigration-focused organization. “Changes in leadership bring new priorities and new focuses for the work.”

Though Arcus has no direct programming of its own, more than $58.4 million in Arcus grants went to small programs and organizations doing LGBT-related work between 2007-2010, making it the largest grant maker to LGBT causes.

“Hearing from organizations in different areas — men who have sex with men [support organizations], HIV-specific projects, younger gay men of color — hearing that organizations have not been getting funded or getting the cold shoulder, is not the worst kept secret in the world,” another prominent LGBT activist told the Blade on condition of anonymity. “The ATM is closed.”

Sources familiar with Arcus said that Burton took seriously her mission to transform the way the Foundation operated and made many staffing changes quickly. One source said that Burton sought to increase grantee accountability and professionalize the organization. The staffing changes, however, may have led to a revolt by some in the organization. Vaid, who ran Arcus for five years, did not respond to emailed interview requests.

Despite the upheaval, other leaders that rely on Arcus dismissed concerns about a shift in focus and expressed confidence in the foundation’s commitment to LGBT causes.

“With Arcus and, actually, all the LGBT funders, they’ve been consistent with their funding over a number of years, and to us and I’m sure to other organizations, that’s extremely important,” said Brad Sears, executive director of the Williams Institute at UCLA, which receives funding from Arcus for its research in the field of LGBT workplace issues. “When you’re hiring people, and you want them to have a job now and in the future, it’s great to have both funding for multiple years, and funding that is at least somewhat more flexible for general operating.”

The Arcus Foundation’s reach is broad. The organization has contributed to everything from the Gill Foundation, the National Gay & Lesbian Task Force and the Transgender Law Center to AIDS and HIV research, small LGBT-welcoming churches, LGBT religious advocacy groups and non-LGBT organizations that develop programming targeting LGBT people of color or other underrepresented groups within the LGBT community.

“We are not an LGBT organization — we are an organization being funded by Arcus because of the work we’re doing to bridge racial justice and LGBT justice,” Krishnamurphy said. “Arcus’s funding in this area [is really] crucial.”

“We wouldn’t have been able to have our GLBT program at all,” said Akaya Windwood, president of the Rockwood Leadership Institute, about Arcus’s contributions. “It made it possible for us to have a robust LGBT program that focuses a lot on communities of color, underrepresented communities within the movement, and rural.”

According to the most recent available IRS forms from 2010, the organization’s total assets were just short of $180 million, most of that being in investments, rather than cash on hand.

The largest single contributor was the organization’s founder, Stryker who gave $30,790,736. The contribution was made in 583,600 shares of Stryker Medical stock. Along with savings and securities interest and dividends, as well as assets on sales of several million dollars worth of assets, the Stryker money made the biggest chunk of the organization’s nearly $50 million in revenue for 2010.

Meanwhile, after expenses and new investments, Arcus contributed $27 million to various LGBT-focused and conservation programs throughout the world in 2010, which — when compared to the Gill Foundation’s nearly $12 million in disbursements that same year — makes Arcus the biggest funder of LGBT programs in the world.

“General operating support from any foundation is really critical for LGBT organizations,” said Masen Davis, executive director of the Transgender Law Center. “There are still too few funders throughout the United States that are supporting LGBT equality and that can make it very difficult for organizations of any size to really work in scale to create change for our community. Arcus has been really important to us and I hope that they continue to be important to our work for years to come.”

Hundreds of LGBT-focused programs at non-profits throughout the nation might not exist if not for Arcus.

“We’re extremely thankful,” said Troy Plummer, executive director of Reconciling Ministries — a group that pushes for LGBT inclusion in the United Methodist Church — explaining that the multi-year grants from Arcus for general operations helped the organization expand programs within the denomination.

“We have been able to consider projects that we would have never considered before the funding from the Arcus Foundation,” Plummer said. “And they were intentionally strategic in wanting to build capacity of our organization, and that was very helpful, and it continues to be helpful in doing so.“

Arcus’s focus on intersectional work — especially in regard to race, religion and age groups — is considered vital for organizations outside what many consider the marriage-focused mainstream of the LGBT movement.

“We’ve observed some drift in traditional funders in amount or percentage allocation toward ‘marriage equality efforts,” said Cindi Love, executive director of SoulForce, whose Equality Ride targeting anti-gay policies at private colleges has been partially funded by an Arcus grant for several years. “Arcus has absolutely from the first day been one of the strongest supporters of the ride because of its emphasis on the development of the next generation of leaders within our movement.”

Amid the nervousness, optimism still springs from the LGBT leaders that continue to rely on Arcus.

“I feel like Arcus has really taken care with their grantees so that they’re able to build and take action when they need to, so shifts in that funding are clearly important to all the grant receivers,” Plummer told the Blade. “I appreciate Arcus rethinking their strategic visioning, and what they want to do to make an impact on a large scale,” saying that he was impressed with the result of the last iteration of the foundation’s strategic plan.

“I don’t know yet whether or not we’re part of that plan,” he added.

“I know that they’re undergoing some strategic planning, and that Arcus has gone through quite a bit of transition, so, we’re all out here cheering them on, and hoping that they get to a really solid place,” said Windwood. “If Arcus thrives then that means that other organizations thrive.”

Federal Government

Trump-appointed EEOC leadership rescinds LGBTQ worker guidance

The EEOC voted to rescind its 2024 guidance, minimizing formally expanded protections for LGBTQ workers.

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission voted 2–1 to repeal its 2024 guidance, rolling back formally expanded protections for LGBTQ workers.

The EEOC, which is composed of five commissioners, is tasked with enforcing federal laws that make workplace discrimination illegal. Since President Donald Trump appointed two Republican commissioners last year — Andrea R. Lucas as chair in January and Brittany Panuccio in October — the commission’s majority has increasingly aligned its work with conservative priorities.

The commission updated its guidance in 2024 under then-President Joe Biden to expand protections to LGBTQ workers, particularly transgender workers — the most significant change to the agency’s harassment guidance in 25 years.

The directive, which spanned nearly 200 pages, outlined how employers may not discriminate against workers based on protected characteristics, including race, sex, religion, age, and disability as defined under federal law.

One issue of particular focus for Republicans was the guidance’s new section on gender identity and sexual orientation. Citing the 2020 U.S. Supreme Court’s Bostock v. Clayton County decision and other cases, the guidance included examples of prohibited conduct, such as the repeated and intentional use of a name or pronoun an individual no longer uses, and the denial of access to bathrooms consistent with a person’s gender identity.

Last year a federal judge in Texas had blocked that portion of the guidance, saying that finding was novel and was beyond the scope of the EEOC’s powers in issuing guidance.

The dissenting vote came from the commission’s sole Democratic member, Commissioner Kalpana Kotagal.

“There’s no reason to rescind the harassment guidance in its entirety,” Kotagal said Thursday. “Instead of adopting a thoughtful and surgical approach to excise the sections the majority disagrees with or suggest an alternative, the commission is throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Worse, it is doing so without public input.”

While this now rescinded EEOC guidance is not legally binding, it is widely considered a blueprint for how the commission will enforce anti-discrimination laws and is often cited by judges deciding novel legal issues.

Multiple members of Congress released a joint statement condemning the agency’s decision to minimize worker protections, including U.S. Reps. Teresa Leger Fernández (D-N.M.), Grace Meng (D-N.Y.), Mark Takano (D-Calif.), Adriano Espaillat (D-N.Y.), and Yvette Clarke (D-N.Y.) The rescission follows the EEOC’s failure to respond to or engage with a November letter from Democratic Caucus leaders urging the agency to retain the guidance and protect women and vulnerable workers.

“The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission is supposed to protect vulnerable workers, including women, people of color, and LGBTQI+ workers, from discrimination on the job. Yet, since the start of her tenure, the EEOC chair has consistently undermined protections for women, people of color, and LGBTQI+ workers. Now, she is taking away guidance intended to protect workers from harassment on the job, including instructions on anti-harassment policies, training, and complaint processes — and doing so outside of the established rule-making process. When workers are sexually harassed, called racist slurs, or discriminated against at work, it harms our workforce and ultimately our economy. Workers can’t afford this — especially at a time of high costs, chaotic tariffs, and economic uncertainty. Women and vulnerable workers deserve so much better.”

Minnesota

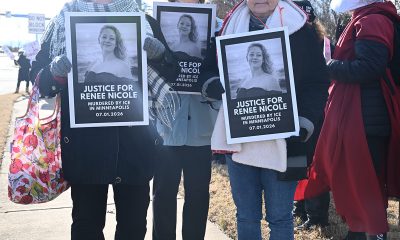

Lawyer representing Renee Good’s family speaks out

Antonio Romanucci condemned White House comments over Jan. 7 shooting

A U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent shot and killed Renee Good in Minneapolis on Jan. 7 as she attempted to drive away from law enforcement during a protest.

Since Good’s killing, ICE has faced national backlash over the excessive use of deadly force, prompting the Trump-Vance administration to double down on escalating enforcement measures in cities across the country.

The Washington Blade spoke with Antonio Romanucci, the attorney representing Good’s family following her death.

Romanucci said that Jonathan Ross — the ICE agent seen on video shooting Good — acted in an antagonizing manner, escalated the encounter in violation of ICE directives, and has not been held accountable as ICE and other federal agents continue to “ramp up” operations in Minnesota.

A day before the fatal shooting, the Department of Homeland Security began what it described as the largest immigration enforcement operation ever carried out by the agency, according to DHS’s own X post.

That escalation, Romanucci said, is critical context in understanding how Good was shot and why, so far, the agent who killed her has faced no consequences for killing a queer mother as she attempted to disengage from a confrontation.

“You have to look at this in the totality of the circumstances … One of the first things we need to look at is what was the mission here to begin with — with ICE coming into Minneapolis,” Romanucci told the Blade. “We knew the mission was to get the worst of the worst, and that was defined as finding illegal immigrants who had felony convictions. When you look at what happened on Jan. 7 with Renee and Rebecca [Good, Renee’s wife], certainly that was far from their mission, wasn’t it? What they really did was they killed a good woman — someone who was a mother, a daughter, a sister, a committed companion, an animal lover.”

Romanucci said finding and charging those responsible for Good’s death is now the focus of his work with her family.

“What our mission is now is to ensure that we achieve transparency, accountability, and justice … We aim to get it in front of, hopefully, a judge or a jury one day to make that determination.”

Those are three things Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and DHS has outright rejected while smearing Good in the official record — including accusing her of being a “domestic terrorist” without evidence and standing by Ross, who Noem said acted in self-defense.

The version of events advanced by Noem and ICE has been widely contradicted by the volume of video footage of the shooting circulating online. Multiple angles show Good’s Honda Pilot parked diagonally in the street alongside other protesters attempting to block ICE agents from entering Richard E. Green Central Park Elementary School.

The videos show ICE officers approaching Good’s vehicle and ordering her to “get out of the car.” She then puts the car in reverse, backs up briefly, shifts into drive, and steers to the right — away from the officers.

The abundance of video evidence directly contradicts statements made by President Donald Trump, Noem, and other administration officials in interviews following Good’s death.

“The video shows that Renee told Jonathan Ross that ‘I’m not mad at you,’ so we know that her state of mind was one of peace,” Romanucci said. “She steered the car away from where he was standing, and we know that he was standing in front of the car. Reasonable police practices say that you do not stand in front of the car when there’s a driver behind the wheel. When you leave yourself with only the ability to use deadly force as an option to escape, that is not a reasonable police practice.”

An autopsy commissioned by Good’s family further supports that account, finding that her injuries were consistent with being shot from the direction of someone driving away.

The autopsy found three gunshot wounds: one to Good’s left forearm, one that struck her right breast without piercing major organs, and a third that entered the left side of her head near the temple and exited on the right side.

Romanucci said Ross not only placed himself directly in harm’s way, but then used deadly force after creating the conditions he claimed justified it — a move that violates DHS and ICE policy, according to former Assistant Homeland Security Secretary Juliette Kayyem.

“As a general rule, police officers and law enforcement do not shoot into moving cars, do not put themselves in front of cars, because those are things that are easily de-escalated,” Kayyem told PBS in a Jan. 8 interview.

“When he put himself in a situation of danger, the only way that he could get out of danger is by shooting her, because he felt himself in peril,” Romanucci said. “That is not a reasonable police practice when you leave yourself with only the ability to use deadly force as an option. That’s what happened here. That’s why we believe, based on what we’ve seen, that this case is unlawful and unconstitutional.”

Romanucci said he was appalled by how Trump and Noem described Good following her death.

“I will never use those words in describing our client and a loved one,” he said. “Those words, in my opinion, certainly do not apply to her, and they never should apply to her. I think the words, when they were used to describe her, were nearly slanderous … Renee Good driving her SUV at two miles per hour away from an ICE agent to move down the street is not an act of domestic terrorism at all.”

He added that his office has taken steps to preserve evidence in anticipation of potential civil litigation, even as the Justice Department has declined to open an investigation.

“We did issue a letter of preservation to the Department of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, and other agencies to ensure that any evidence that’s in their possession be not destroyed or altered or modified,” Romanucci said. “We’ve heard Todd Blanche say just in the last couple of days that they don’t believe that they need to investigate at all. So we’re going to be demanding that the car be returned to its rightful owner, because if there’s no investigation, then we want our property back.”

The lack of accountability for Ross — and the continued expansion of ICE operations — has fueled nationwide protests against federal law enforcement under the Trump-Vance administration.

“The response we’ve seen since Renee’s killing has been that ICE has ramped up its efforts even more,” Romanucci said. “There are now over 3,000 ICE agents in a city where there are only 600 police officers, which, in my opinion, is defined as an invasion of federal law enforcement officers into a city … When you see the government ramping up its efforts in the face of constitutional assembly, I think we need to be concerned.”

As of now, Romanucci said, there appears to be no meaningful accountability mechanism preventing ICE agents from continuing to patrol — and, in some cases, terrorize — the Minneapolis community.

“What we know is that none of these officers are getting disciplined for any of their wrongdoings,” he said. “The government is saying that none of their officers have acted in a wrongful manner, but that’s not what the courts are saying … Until they get disciplined for their wrongdoings, they will continue to act with impunity.”

When asked what the public should remember about Good, Romanucci emphasized that she was a real person — a mother, a wife, and a community member whose life was cut short. Her wife lost her partner, and three children lost a parent.

“I’d like the public to remember Renee about is the stories that Rebecca has to tell — how the two of them would share road trips together, how they loved to share home-cooked meals together, what a good mother she was, and what a community member she was trying to make herself into,” Romanucci said. “They were new to Minneapolis and were really trying to make themselves a home there because they thought they could have a better life. Given all of that, along with her personality of being one of peace and one of love and care, I think that’s what needs to be remembered about Renee.”

The White House

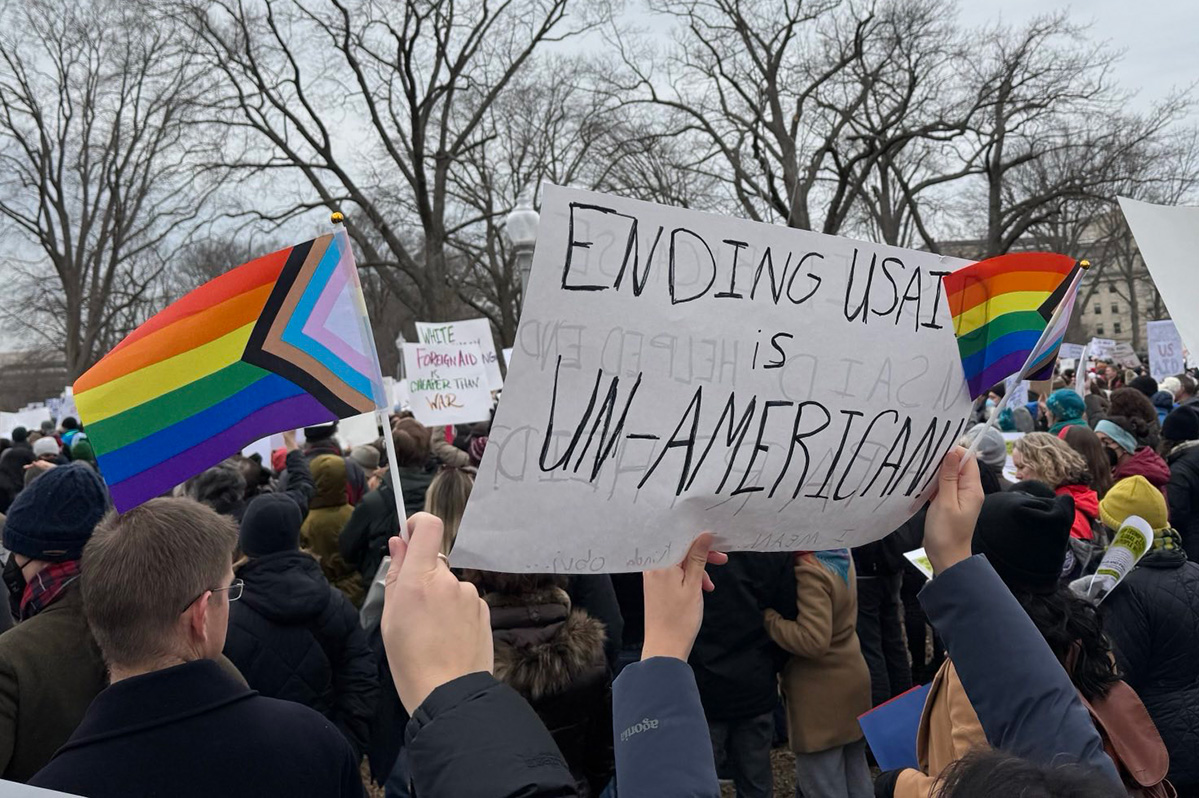

Trump-Vance administration ‘has dismantled’ US foreign policy infrastructure

Current White House took office on Jan. 20, 2025

Jessica Stern, the former special U.S. envoy for the promotion of LGBTQ and intersex rights, on the eve of the first anniversary of the Trump-Vance administration said its foreign policy has “hurt people” around the world.

“The changes that they are making will take a long time to overturn and recover from,” she said on Jan. 14 during a virtual press conference the Alliance for Diplomacy and Justice, a group she co-founded, co-organized.

Amnesty International USA National Director of Government Relations and Advocacy Amanda Klasing, Human Rights Watch Deputy Washington Director Nicole Widdersheim, Human Rights First President Uzra Zeya, PEN America’s Jonathan Friedman, and Center for Reproductive Rights Senior Federal Policy Council Liz McCaman Taylor also participated in the press conference.

The Trump-Vance administration took office on Jan. 20, 2025.

The White House proceeded to dismantle the U.S. Agency for International Development, which funded LGBTQ and intersex rights organizations around the world.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio last March announced the State Department would administer the 17 percent of USAID contracts that had not been cancelled. Rubio issued a waiver that allowed PEPFAR and other “life-saving humanitarian assistance” programs to continue to operate during the U.S. foreign aid freeze the White House announced shortly after it took office.

The global LGBTQ and intersex rights movement has lost more than an estimated $50 million in funding because of the cuts. The Washington Blade has previously reported PEPFAR-funded programs in Kenya and other African countries have been forced to suspend services and even shut down.

Stern noted the State Department “has dismantled key parts of foreign policy infrastructure that enabled the United States to support democracy and human rights abroad” and its Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor “has effectively been dismantled.” She also pointed out her former position and others — the Special Representative for Racial Equity and Justice, the Ambassador-at-Large for Global Women’s Issues, and the Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice — “have all been eliminated.”

President Donald Trump on Jan. 7 issued a memorandum that said the U.S. will withdraw from the U.N. Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women and more than 60 other U.N. and international entities.

Rubio in a Jan. 10 Substack post said UN Women failed “to define what a woman is.”

“At a time when we desperately need to support women — all women — this is yet another example of the weaponization of transgender people by the Trump administration,” said Stern.

US ‘conducting enforced disappearances’

The Jan. 14 press conference took place a week after a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent killed Renee Good, a 37-year-old woman who left behind her wife and three children, in Minneapolis. American forces on Jan. 3 seized now former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, at their home in Caracas, the Venezuelan capital, during an overnight operation. Trump also continues to insist the U.S. needs to gain control of Greenland.

Widdersheim during the press conference noted the Trump-Vance administration last March sent 252 Venezuelans to El Salvador’s Terrorism Confinement Center, a maximum-security prison known by the Spanish acronym CECOT.

One of them, Andry Hernández Romero, is a gay asylum seeker who the White House claimed was a member of Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang the Trump-Vance administration has designated as an “international terrorist organization.” Hernández upon his return to Venezuela last July said he suffered physical, sexual, and psychological abuse while at CECOT.

“In 2025 … the United States is conducting enforced disappearances,” said Widdersheim.

Zeya, who was Under Secretary of State for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights from 2021-2025, in response to the Blade’s question during the press conference said her group and other advocacy organizations have “got to keep doubling down in defense of the rule of law, to hold this administration to account.”

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoCompanies participate in ‘Pride on the Promenade’ at World Economic Forum

-

Movies5 days ago

Movies5 days agoFew openly queer nominees land Oscar nominations

-

Noticias en Español5 days ago

Noticias en Español5 days agoEl 2026 bajo presión

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoJudge denies D.C. request to dismiss gay police captain’s anti-bias lawsuit