Arts & Entertainment

‘Hello Gorgeous’

Gay biographer deconstructs Streisand’s ascent to superstardom

Jewish Literary Festival: William Mann

Closing Night

Wednesday, 7:30 p.m.

D.C. Jewish Community Center

1529 16th Street, NW

Tickets: $10

Barbra Streisand in the recording studio for Columbia in New York, mid-1960s. (Photo from the Collection of Stuart Lippner, courtesy Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

It’s an interesting time for Barbra Streisand fans.

She’s on tour and played New York last weekend (no D.C. dates scheduled).

A (sort of) new album dropped Oct. 9 called “Release Me” that collects 11 previously unreleased outtakes from various album projects going back to the beginning of her career in the early ‘60s. The faithful legion, of course, are beside themselves finally getting to hear rare cuts like her interpretations of Jimmy Webb’s “Didn’t We” and “Home” from “The Wiz.” Her MusiCares tribute concert, in which she was serenaded last year by Diana Krall, Barry Mainlow, Seal, Stevie Wonder and others, is out on DVD and Blu-ray from Shout! Factory Nov. 13.

But just as interesting is the new book “Hello, Gorgeous: Becoming Barbra Streisand,” also released this month from gay author William J. Mann, who, in addition to several novels, has penned well-received bios on William Haines, John Schlesinger, Katharine Hepburn and Elizabeth Taylor. Mann, an iconoclast who doesn’t smash his subjects but delights in deconstructing widely parsed anecdotes of show biz folklore, zeroes in on Streisand’s early years from early 1960 (when she was 17) to the spring of ’64 by which time she had opened in the long-delayed “Funny Girl” on Broadway and recorded three platinum-selling albums for Columbia.

Mann focuses on her early years because he says “everything we think we know about her can be traced back to this seminal period … She arrived in New York in 1959 as a penniless teenager without any connections or experience. Less than five years later she was the top-selling female recording artist in the country and the star of one of Broadway’s biggest smash hits. Going in as close as I have in this book has allowed me to really shed light on how she accomplished such a feat.”

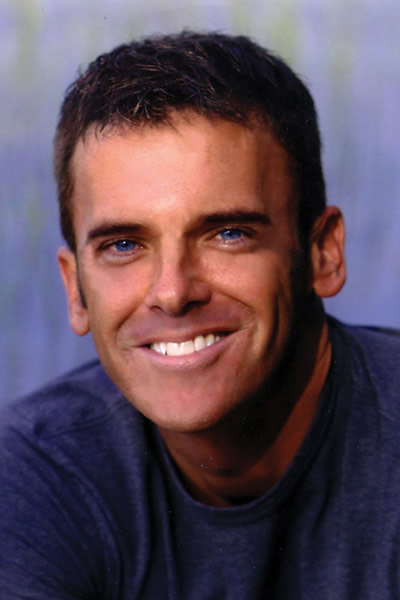

Mann’s in Washington Wednesday on his book tour at the D.C. Jewish Community Center for a 7 p.m. Streisand presentation after which he’ll sign copies of the book. During two phone chats this week, the 49-year-old author talked about the process of bringing the book — he wasn’t particularly a Streisand fan before — to fruition and how writing it compared to his mammoth Hepburn and Taylor tomes.

Mann says focusing on Streisand’s early years turned out to be an unexpected advantage. Because few of the key players are still in touch with the notoriously private and exacting legend, they felt freer, Mann says, to cooperate. He wasn’t on a mission to bash Streisand, but he did want an honest and fresh take.

“These very, very famous people really live in a bubble,” he says. “It becomes virtually impossible to get an unvarnished opinion because any colleague you talk to is going to have nothing but superlatives and that becomes very difficult. … About 90 percent of the people I spoke to didn’t continue on with her. … so they could be candid. They didn’t have to think, ‘Gee, is Barbra gonna be pissed at me, I have to work with her next month.’”

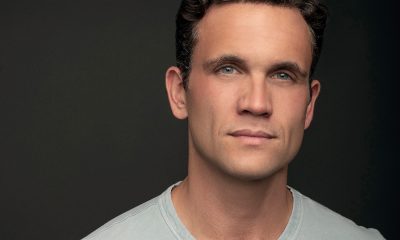

Gay historian and author William J. Mann (Photo by Michael Childers; courtesy Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

Despite calling the book “notable for its breadth of detail and fair mindedness,” biographer James Gavin writing for the New York Times said “little” of the book is new, a point Mann counters with his biggest coup — being granted the right to delve into the Jerome Robbins (the Broadway legend who worked on “Funny Girl”) papers at the New York Public Library, which had not previously been plumbed for any Streisand book and are not available to researchers (Mann got an exception through the Robbins’ estate).

And even though Streisand’s first boyfriend, Barry Dennen has written an entire book (1997’s “My Life with Barbra”) on their relationship, Mann says he got fresh material from the gay actor for “Gorgeous.”

One of Mann’s favorite experiences was visiting Phyllis Diller, who became a pal and mentor of the young Streisand during their time performing at seedy New York nightclub the Bon Soir in the early ‘60s. (Diller died in August.)

“She was such a hoot,” Mann says with a laugh. “That interview was probably the most enjoyable of the process. I got to go to her house and she was flirting and laughing. I asked her if she’d give me one of her trademark laughs and she did. I just sat there thinking, ‘I love my job.’”

Other “gets” weren’t so splashy but proved equally invaluable. Though scads of Streisand material has been released and is on YouTube, Mann says the Streisand aficionados — almost all gay — were helpful. He thinks his track record on the Hepburn and Taylor books helped open doors on several fronts.

“There’s one fan, and of course he’s made me promise never to reveal who he is, who had some really amazing stuff. There was a DVD (Streisand) was planning to put out maybe five-six years ago of all her old TV appearances but for whatever reason, it never came out. This guy had a bootleg copy of it, which was extraordinarily helpful. Another fan had some of her original contracts. Which is crazy. Who knows how they get this stuff. You’d think she’d have those herself, but somehow they had them and those were very helpful as well. And of course once you get in those fan circles, one things leads to another and another. I didn’t write it for the fans, because then you’d end up censoring it to please them, but they were a great help.”

Early signs are good.

According to Nielsen BookScan, the book has already sold about 2,000 copies. And a glowing USA Today review said Mann’s “meticulous research and insightful analysis go deeper than any previous (Streisand) biography.” Liz Smith called it “excellent.” Amazon reader feedback has been highly positive and perhaps the surest sign that the writer did his homework, there’s been nary a peep, at least so far, from the Streisand camp (she devotes a whole section of her official website to debunking what’s written about her — check out the juicy reads on her tangles with Larry Kramer over a never-made film adaptation of “The Normal Heart” she wanted to do).

At more than 500 pages, “Gorgeous” makes for a lengthy yet brisk read. Mann, who splits his time between New York and Provincetown (where he does most of his writing), is happy to engage a few questions the book inspires, one common enough that he’s written a Huffington Post piece on the topic: that is, surely it’s no coincidence that Streisand, who had several key gay men in her life very early on in her career, ended up one of the biggest gay entertainment icons of all time, right?

“It’s not a coincidence at all,” he says. “She was shaped by so many gay influences … in various ways. The way she dressed, the way she put a song across, the way she styled her songs, they way she interacted with an audience, it’s so obvious all her early mentors were gay and I believe that when those early audiences went to see her, they responded to something familiar. The way she laughed, the way she moved, her campy humor. There was something there gay men recognized and thought, ‘Oh, we can relate to this chick.’ And she was not the first one to have this happen either. It goes all the way back to Mae West and the drag queens she worked with in New York. You see it with Judy (Garland) with Roger Edens, with Joan Crawford and Billy Haines … with Madonna it was the same thing.”

Barbra Streisand with first husband, actor Elliott Gould en route to the Tony Awards on April 29, 1962. (Photo from the collection of Stuart Lippner, courtesy Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

And since Mann, with the Taylor and Streisand books especially, has focused on the nature of fame and how it was achieved — a dissection of the lucky breaks versus the raw material — another question occurs: given Streisand’s undeniable talent and famous drive, was her legend and success inevitable?

Mann says no.

“She would like us to think that, but no, I don’t think it was at all. I think she benefited form some really shrewed salesmanship and a degree of luck. Just the fact that there were some major parts with ‘I Can Get it For You Wholesale’ and “Funny Girl’ for unusual looking Jewish girls, she was lucky that she was there for those parts at the time they came along. Of course she’s brilliantly talented but there are lots of people who were. You hear some of these other singers from the nightclub era like Blossom Dearie or Joanna Beretta and you’re like, ‘Wow, they’re every bit as good as Barbra,’ but they lacked something — either a very shrewd publicity campaign on their behalf or perhaps their own ambition … it took a terrific amount of PR to make it happen.”

Game time: Kate, Liz or Babs?

William J. Mann has written well-received bios of three of the most famous legends the 20th century produced: Katharine Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor and now, Barbra Streisand. At the end of an interview, Mann was game for a “lightening round” in which he considers how the three icons stack up. He had to answer each question with one of the three names.

Of the three, which had:

- the most raw talent? “Streisand”

- the most career triumphs? “Taylor”

- Was the most personally content? “Taylor”

- Whose personality evolved the most over the decades? “Hepburn”

- Which was the most fan friendly? “Taylor, by far.”

- The most private? “Streisand. Hepburn was private, but she also put things out there, although not always her true self. So I guess Streisand.”

- Whose work has best stood the test of time? “That’s kind of a draw. They all have. You look at Hepburn in a film like “Alice Adams,” which is this beautiful, brilliant, heartbreaking film that totally stands up. Or Elizabeth in ‘Virginia Woolf’ and you just think, ‘Wow, nobody could have done that better.’ Or one of Barbra’s albums.”

- Which had (or has) the most ardent fans? “Streisand”

- Was the toughest to research? “I suppose Hepburn but she had just passed away so that opened some doors. The other two were alive when I was writing.” (Taylor died shortly after the Mann book came out.)

- Had the most gays in her personal life? “Taylor”

- Had the easiest path to stardom? “Taylor. It was practically handed to her.”

- The toughest? “Streisand, even though it was really fast.”

- And just for fun, any word on how Streisand or Hepburn felt about tying for the Best Actress Oscar in ’68? “They both probably hated to share it,” he says. “Hepburn made a big show of not caring about the Oscars but of course she cared a great deal. … Streisand was very gracious when she accepted (Hepburn did not attend) and said she was ‘in great company.’ It was probably unlike either of them to send the other a congratulatory note, but I don’t fully know the answer to that or whether anybody ever tried to get them together for a photo. I suspect neither of them would have been too wild about that.”

— Joey DiGuglielmo

Friday, Feb. 20

Center Aging Monthly Luncheon with Yoga will be at noon at the D.C. LGBTQ+ Community Center. Email Mac at [email protected] if you require ASL interpreter assistance, have any dietary restrictions, or questions about this event.

Trans and Genderqueer Game Night will be at 7 p.m. at the D.C. Center. This will be a relaxing, laid-back evening of games and fun. All are welcome! We’ll have card and board games on hand. Feel free to bring your own games to share. For more details, visit the Center’s website.

Go Gay DC will host “First Friday LGBTQ+ Community Social” at 7 p.m. at Hotel Zena. This is a chance to relax, make new friends, and enjoy happy hour specials at this classic retro venue. Attendance is free and more details are available on Eventbrite.

Saturday, Feb. 21

Go Gay DC will host “LGBTQ+ Community Brunch” at 11 a.m. at Freddie’s Beach Bar & Restaurant. This fun weekly event brings the DMV area LGBTQ community, including allies, together for delicious food and conversation. Attendance is free and more details are available on Eventbrite.

LGBTQ People of Color will be at 7 p.m. on Zoom. This peer support group is an outlet for LGBTQ People of Color to come together and talk about anything affecting them in a space that strives to be safe and judgement free. There are all sorts of activities like watching movies, poetry events, storytelling, and just hanging out with others. For more information and events, visit thedccenter.org/poc or facebook.com/centerpoc.

Sunday, Feb. 22

Queer Talk DC will host “The Black Gay Flea Market” at 1 p.m. at Doubles in Petworth. There will be more than 15 Black queer vendors from all over the DMV in one spot. The event’s organizers have reserved the large back patio for all vendors, and the speak easy for bar service, which will be serving curated cocktails made just for the event (cash bar.) DJ Fay and DJ Jam 2x will be spinning the entire event. For more details, visit Eventbrite.

Monday, Feb. 23

“Center Aging: Monday Coffee Klatch” will be at 10 a.m. on Zoom. This is a social hour for older LGBTQ adults. Guests are encouraged to bring a beverage of choice. For more information, contact Adam at [email protected].

Tuesday, Feb. 24

Coming Out Discussion Group will be at 7 p.m. on Zoom. This is a safe space to share experiences about coming out and discuss topics as it relates to doing so — by sharing struggles and victories the group allows those newly coming out and who have been out for a while to learn from others. For more details, visit the group’s Facebook.

Genderqueer DC will be at 7 p.m. on Zoom. This is a support group for people who identify outside of the gender binary, whether you’re bigender, agender, genderfluid, or just know that you’re not 100 percent cis. For more details, visit genderqueerdc.org or Facebook.

Wednesday, Feb. 25

Job Club will be at 6 p.m. on Zoom upon request. This is a weekly job support program to help job entrants and seekers, including the long-term unemployed, improve self-confidence, motivation, resilience and productivity for effective job searches and networking — allowing participants to move away from being merely “applicants” toward being “candidates.” For more information, email [email protected] or visit thedccenter.org/careers.

Asexual and Aromantic Group will meet at 7 p.m. on Zoom. This is a space where people who are questioning this aspect of their identity or those who identify as asexual and/or aromantic can come together, share stories and experiences, and discuss various topics. For more details, email [email protected].

Thursday, Feb. 26

The DC Center’s Fresh Produce Program will be held all day at the DC Center. To be more fair with who is receiving boxes, the program is moving to a lottery system. People will be informed on Wednesday at 5 p.m. if they are picked to receive a produce box. No proof of residency or income is required. For more information, email [email protected] or call 202-682-2245.

Virtual Yoga Class will be at 7 p.m. on Zoom. This free weekly class is a combination of yoga, breathwork and meditation that allows LGBTQ community members to continue their healing journey with somatic and mindfulness practices. For more details, visit the DC Center’s website.

Sports

US wins Olympic gold medal in women’s hockey

Team captain Hilary Knight proposed to girlfriend on Wednesday

The U.S. women’s hockey team on Thursday won a gold medal at the Milan Cortina Winter Olympics.

Team USA defeated Canada 2-1 in overtime. The game took place a day after Team USA captain Hilary Knight proposed to her girlfriend, Brittany Bowe, an Olympic speed skater.

Cayla Barnes and Alex Carpenter — Knight’s teammates — are also LGBTQ. They are among the more than 40 openly LGBTQ athletes who are competing in the games.

The Olympics will end on Sunday.

Movies

Radical reframing highlights the ‘Wuthering’ highs and lows of a classic

Emerald Fennell’s cinematic vision elicits strong reactions

If you’re a fan of “Wuthering Heights” — Emily Brontë’s oft-filmed 1847 novel about a doomed romance on the Yorkshire moors — it’s a given you’re going to have opinions about any new adaptation that comes along, but in the case of filmmaker Emerald Fennell’s new cinematic vision of this venerable classic, they’re probably going to be strong ones.

It’s nothing new, really. Brontë’s book has elicited controversy since its first publication, when it sparked outrage among Victorian readers over its tragic tale of thwarted lovers locked into an obsessive quest for revenge against each other, and has continued to shock generations of readers with its depictions of emotional cruelty and violent abuse, its dysfunctional relationships, and its grim portrait of a deeply-embedded class structure which perpetuates misery at every level of the social hierarchy.

It’s no wonder, then, that Fennell’s adaptation — a true “fangirl” appreciation project distinguished by the radical sensibilities which the third-time director brings to the mix — has become a flash point for social commentators whose main exposure to the tale has been flavored by decades of watered-down, romanticized “reinventions,” almost all of which omit large portions of the novel to selectively shape what’s left into a period tearjerker about star-crossed love, often distancing themselves from the raw emotional core of the story by adhering to generic tropes of “gothic romance” and rarely doing justice to the complexity of its characters — or, for that matter, its author’s deeper intentions.

Fennell’s version doesn’t exactly break that pattern; she, too, elides much of the novel’s sprawling plot to focus on the twisted entanglement between Catherine Earnshaw (Margot Robbie), daughter of the now-impoverished master of the titular estate (Martin Clunes), and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi), a lowborn child of unknown background origin that has been “adopted” by her father as a servant in the household. Both subjected to the whims of the elder Earnshaw’s violent temper, they form a bond of mutual support in childhood which evolves, as they come of age, into something more; yet regardless of her feelings for him, Cathy — whose future status and security are at risk — chooses to marry Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif), the financially secure new owner of a neighboring estate. Heathcliff, devastated by her betrayal, leaves for parts unknown, only to return a few years later with a mysteriously-obtained fortune. Imposing himself into Cathy’s comfortable-but-joyless matrimony, he rekindles their now-forbidden passion and they become entwined in a torrid affair — even as he openly courts Linton’s naive ward Isabella (Alison Oliver) and plots to destroy the entire household from within. One might almost say that these two are the poster couple for the phrase “it’s complicated.” and it’s probably needless to say things don’t go well for anybody involved.

While there is more than enough material in “Wuthering Heights” that might easily be labeled as “problematic” in our contemporary judgments — like the fact that it’s a love story between two childhood friends, essentially raised as siblings, which becomes codependent and poisons every other relationship in their lives — the controversy over Fennell’s version has coalesced less around the content than her casting choices. When the project was announced, she drew criticism over the decision to cast Robbie (who also produced the film) opposite the younger Elordi. In the end, the casting works — though the age gap might be mildly distracting for some, both actors deliver superb performances, and the chemistry they exude soon renders it irrelevant.

Another controversy, however, is less easily dispelled. Though we never learn his true ethnic background, Brontë’s original text describes Heathcliff as having the appearance of “a dark-skinned gipsy” with “black fire” in his eyes; the character has typically been played by distinctly “Anglo” men, and consequently, many modern observers have expressed disappointment (and in some cases, full-blown outrage) over Fennel’s choice to use Elordi instead of putting an actor of color for the part, especially given the contemporary filter which she clearly chose for her interpretation for the novel.

In fact, it’s that modernized perspective — a view of history informed by social criticism, economic politics, feminist insight, and a sexual candor that would have shocked the prim Victorian readers of Brontë’s novel — that turns Fennell’s visually striking adaptation into more than just a comfortably romanticized period costume drama. From her very opening scene — a public hanging in the village where the death throes of the dangling body elicit lurid glee from the eagerly-gathered crowd — she makes it oppressively clear that the 18th-century was not a pleasant time to live; the brutality of the era is a primal force in her vision of the story, from the harrowing abuse that forges its lovers’ codependent bond, to the rigidly maintained class structure that compels even those in the higher echelons — especially women — into a kind of slavery to the system, to the inequities that fuel disloyalty among the vulnerable simply to preserve their own tenuous place in the hierarchy. It’s a battle for survival, if not of the fittest then of the most ruthless.

At the same time, she applies a distinctly 21st-century attitude of “sex-positivity” to evoke the appeal of carnality, not just for its own sake but as a taste of freedom; she even uses it to reframe Heathcliff’s cruel torment of Isabella by implying a consensual dom/sub relationship between them, offering a fragment of agency to a character typically relegated to the role of victim. Most crucially, of course, it permits Fennell to openly depict the sexuality of Cathy and Heathcliff as an experience of transgressive joy — albeit a tormented one — made perhaps even more irresistible (for them and for us) by the sense of rebellion that comes along with it.

Finally, while this “Wuthering Heights” may not have been the one to finally allow Heathcliff’s ambiguous racial identity to come to the forefront, Fennell does employ some “color-blind” casting — Latif is mixed-race (white and Pakistani) and Hong Chau, understated but profound in the crucial role of Nelly, Cathy’s longtime “paid companion,” is of Vietnamese descent — to illuminate the added pressures of being an “other” in a world weighted in favor of sameness.

Does all this contemporary hindsight into the fabric of Brontë’s epic novel make for a quintessential “Wuthering Heights?” Even allowing that such a thing were possible, probably not. While it presents a stylishly crafted and thrillingly cinematic take on this complex classic, richly enhanced by a superb and adventurous cast, it’s not likely to satisfy anyone looking for a faithful rendition, nor does it reveal a new angle from which the “romance” at its center looks anything other than toxic — indeed, it almost fetishizes the dysfunction. Even without the thorny debate around Heathcliff’s racial identity, there’s plenty here to prompt purists and revisionists alike to find fault with Fennell’s approach.

Yet for those looking for a new window into to this perennial classic, and who are comfortable with the radical flourish for which Fennell is already known, it’s an engrossing and intellectually stimulating exploration of this iconic story in a way that exchanges comfortable familiarity for unpredictable chaos — and for cinema fans, that’s more than enough reason to give “Wuthering Heights” a chance.

-

Baltimore4 days ago

Baltimore4 days ago‘Heated Rivalry’ fandom exposes LGBTQ divide in Baltimore

-

Real Estate4 days ago

Real Estate4 days agoHome is where the heart is

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoDeon Jones speaks about D.C. Department of Corrections bias lawsuit settlement

-

European Union4 days ago

European Union4 days agoEuropean Parliament resolution backs ‘full recognition of trans women as women’