Opinions

Will gay and lesbian neighborhoods resurge?

Trump-Pence era underscores importance of LGBT communities

Dupont Circle (Washington Blade file photo by Michael Key)

The election of Donald Trump portends—if not darker days—certainly more gloomy days ahead for America’s LGBT community. President-elect Trump’s proposed policy agenda seems designed to marginalize minority groups, and Vice President-elect Pence has a demonstrated track record of vigorously working to restrict LGBT rights. The tone set by their transition team has already proven to be disappointing news for America’s lesbian and gay community members, many of whom live, socialize and patronize businesses in or near gay neighborhoods in urban centers squarely within progressive “blue” territory.

Gay neighborhoods—Chelsea and Greenwich Village (NYC), South End (Boston), North Halsted (Chicago), West Hollywood (Los Angeles), South Beach (Miami), and Dupont Circle (Washington, D.C.)—along with countless similar neighborhoods in medium- and large-sized urban centers, are vital places in urban America. These neighborhoods emerged after the 1960s sexual revolution and concurrent violence against gay men and lesbian women, including landmark events such as the Stonewall riots in New York and the UpStairs arson in New Orleans, in which more than thirty patrons perished. A desire to live in accepting communities galvanized gay men and lesbian women to become ‘urban pioneers,’ the first group to occupy older and declining central city neighborhoods as affluent residents fled cities for the suburbs. Gay and lesbian residents established communities in these neglected urban areas, where rents were inexpensive, space was plentiful, and safety was strengthened by numbers. Over time, through dedication, hard work and often in the face of adversity, LGBT residents invested in these communities by renovating homes and apartment buildings. New businesses and other investment were soon attracted to these vibrant neighborhoods, and the combined community-building efforts richly enhanced social and cultural life.

The latest trends, however, measured through demographic data, economic activity, and housing market performance, suggested the slow demise of gay urban neighborhoods for three key reasons. First, older gays and lesbians continue to assimilate in urban space and no longer feel a strong desire to live in gay neighborhoods, as fears for physical safety decrease and mainstream acceptance increases. Second, millennial LGBTs, coming of age in a time of greater acceptance, show more interest in integrating rather than segregating and are content trading propinquity for digital connection. Third, long-established gay neighborhoods, in desirable locations with quality housing and attractive amenities resulting from significant neighborhood investment, became appealing to mainstream buyers and residents. In this sense, gay neighborhoods became victims of their own success.

The outcome of the 2016 presidential election has placed LGBT Americans on edge. Seemingly rational trajectories of mainstreaming LGBT Americans—greater legal protections and equity under federal law, ever-increasing social acceptance, diminishing risk of discrimination and increasing safety—are now seriously threatened as a new and evidently conservative regime takes control of the American government. Many fear that the hard-won social advances of the LGBT community will be rolled back.

When candidate Trump says on the stump that “inner cities are a disaster,” he stokes fears—among rural and suburban Americans—from decades past when cities were dangerous, and crime-ridden. The vibrant, successful cities that drive our American economy today demonstrate that this rhetoric is unacceptable, and propagating empty allusions represents a significant step backward for urban America and especially LGBT neighborhoods. Donald Trump and Mike Pence should visit gay and lesbian neighborhoods to acquire a clearer understanding of the positive impact that LGBT residents, parents, and families have had in fueling our American economy while ensuring prosperity in their communities for everyone to enjoy, regardless of sexual orientation.

Perhaps one of the more disappointing changes to come is the likely death of a quiet effort just getting underway by the Department of the Interior, on behalf of the Obama administration, to identify and designate historically significant LGBT heritage sites across America. This potential loss is significant and should motivate LGBT Americans and community leaders to unite and advocate the continuation of this little-known but important initiative.

Since Nov. 8, there has been an outpouring of togetherness among LGBT community members via social media and public demonstrations. While the LGBT community celebrates many advances against discrimination based on sexual orientation, greater integration into mainstream society, heightened visibility, and increased confidence, fear clouds the present frame of reference. Segregation is a natural human response derived from fear of others, and to imagine a future when urban American becomes more divided—whether people separate themselves into neighborhoods because they choose to or they are forced to—undoes advances our country has made in creating an open, accepting, and tolerant society. People are again seeking kinship with others who feel similarly marginalized, and this might mean that gay neighborhoods, with their self-protective and sometimes outspoken nature, may again rise, but hopefully not as communities of last resort for America’s LGBT citizens.

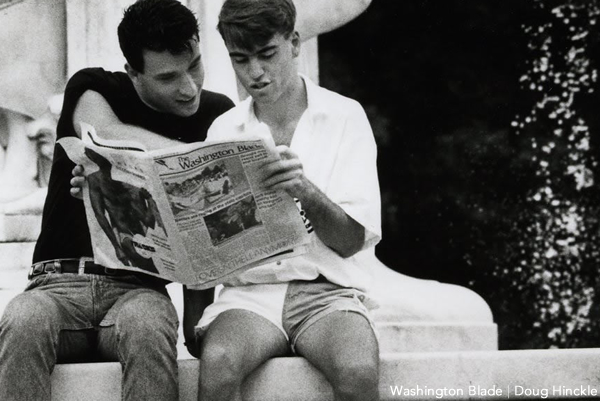

Two young men read the ‘Washington Blade’ at Dupont Circle in 1991. Dupont Circle was once a center of LGBT life in Washington, D.C. (Washington Blade archive photo by Doug Hinckle)

Alex Bitterman, Ph.D., is professor and Chair of Architecture and Design at Alfred State College. Daniel Baldwin Hess, Ph.D., is professor of Urban Planning at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York and Visiting Scholar at the Centre for Migration and Urban Studies at the University of Tartu, Estonia.

Opinions

Capital Pride must be transparent about sexual misconduct investigation

More questions than answers after two board members resign

We are living through some very difficult times in our country. We have a felon in the White House who has surrounded himself with incompetent sycophants and fascists. A Congress that bows down to him, often based on his threats. Things have gotten so bad that his supporters are beginning to wake up to the fact that he cares not a whit for them. They are demanding he stop hiding his involvement with the convicted sex trafficker, Jeffrey Epstein, and come clean. So, to distract them from this, he began a war in the Middle East in which members of the American military have already lost their lives. He says more lives will be lost. He hopes this war of distraction will have Americans forget his failed domestic policies and the Epstein scandal.

But at the same time that all of this is happening, I am forced to look around at organizations I support and ask if they are being open and honest in the way we are demanding of the felon in the White House.

Recently, I have received calls about an organization I have the utmost pride in: Capital Pride. The calls are about Capital Pride’s internal investigation of “a claim” made against a former board chair, who resigned and no longer has any role with the organization. There has been no public proof of any wrongdoing. At the time, Capital Pride announced it had retained an “independent firm” to investigate the complaint. Now, more than four months later, a second board member has resigned sharing her letter of resignation with the Blade.

Taylor Lianne Chandler, a member of the Capital Pride board of directors since 2019 who served as the board’s secretary, submitted a letter of resignation on Feb. 24 that alleges the board has failed to address instances of “sexual misconduct” at Capital Pride.

“This board has made its priorities clear through its actions: protecting a sexual predator matters more than protecting the people who had the courage to come forward. … I have been targeted, bullied, and made to feel like an outsider for doing what any person of integrity would do – telling the truth,” Chandler wrote in her resignation letter.

The Blade reported the organization announced, “As we continue to grow our organization, we’re proactively strengthening the policies and procedures that shape our systems, our infrastructure, and the support we provide to our team and partners.”

Again, it is four months later, and there has been no information from Capital Pride regarding that investigation.

Chandler said a Capital Pride investigation identified one individual implicated in a “pattern” of sexual harassment related behavior over a period of time. She added she was bound by a Non-Disclosure Agreement that applies to all board members and she cannot disclose the name of the person implicated in alleged sexual misconduct or those who came forward to complain about it. She added, “It was one individual, but there was a pattern and a history.”

Again, reading that letter from Chandler and because of the news being full of the Epstein scandal, it makes me want assurances that no organization representing my community will ever think it can cover up issues like this. Capital Pride leadership must be totally transparent.

Capital Pride is a wonderful organization with so many incredible people working and volunteering there. They make our community proud. I never want to see a blemish on the organization. So, I am calling on them to be open and transparent about the investigation they themselves announced, and let the community know what they found, in detail. More important even than the entire community knowing, is for their staff and volunteers to know what they found. No one should be bound by an NDA, which leads to people thinking something really bad is going on.

I thought twice, even three times, before writing this column. I don’t want it to be seen as casting aspersions on all of Capital Pride, or anyone who may have worked there, or volunteered there. But again, because of the focus on the Epstein scandal, and my writing about the felon and his Cabinet officials involved in it, my calling for them to come clean and tell us all they know, I feel compelled to say the same to the organization I have supported over the years, which even honored me as a Capital Pride Hero in 2016. I want them to move forward and be a beacon of light for our community for many years to come. The work they do makes a difference for so many.

I wrote in my memoir that coming to a Pride event helped me to come out, and I am sure it has done the same for so many others in our community. What Capital Pride does is important and it must be as transparent as we demand of any other organization.

Peter Rosenstein is a longtime LGBTQ rights and Democratic Party activist.

Opinions

An undeclared war of distraction by the felon

Will Trump claim a national emergency to undermine midterms?

The president of the United States in his rambling speech about our attack on Iran, recorded during a campaign trip, said, “The Iranian regime seeks to kill. The lives of courageous American heroes may be lost and we may have casualties — that often happens in war — but we’re doing this not for now. We’re doing this for the future, and it is a noble mission.”

Well, the United States has not declared war on Iran, only Congress can do that, not the president. As I write this, the felon has yet to make a live speech to the American people about what he is doing, and Americans have already lost their lives. He is weekending as he usually does at Mar-a-Lago. I wonder if he has the balls to head out to the golf course while American lives continue to be at stake.

This operation is clearly the felon’s way of distracting the people of the United States from his failed domestic policies. From rising food prices, rents, and health insurance. From the loss of manufacturing jobs, as reported in November ”manufacturing shed another 6,000 jobs in September, for a total loss of 58,000 since April.” Had he not acted on Iran now every news outlet in the nation would have reported on the Epstein scandal with the release of the depositions, video and transcripts, of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and former President Bill Clinton, in front of the Congressional Oversight Committee.

Even more frightening is this may be his way of preparing to claim a national emergency to undermine the midterm elections, which he is clearly on target to lose, now that his Save America Act has been defeated in Congress.

Americans must ask themselves how long they will put up with this warmonger, racist, sexist, lying, homophobic, SOB, who cares not a whit for them, but only for himself, and his rich colleagues, taking as much grift as they all can, while he is president.

None of this is to say we shouldn’t put constraints on Iran, work to see they never have a nuclear bomb, and limit their production of missiles. We were working toward the goal of stopping them from having a nuclear bomb when the felon, in his first term, pulled us out of the agreement to move forward on that. Today, he has sidelined the State Department, and his Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, in negotiations, and has relied on his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, and Steve Witkoff. The attack was commenced while negotiations were underway. At the end of last week it was reported, Oman’s Foreign Minister Badr Al-Busaidi, who mediated the talks in Geneva, said there had been “significant progress in the negotiation.” Al-Busaidi added, “Technical-level talks would continue next week in Vienna, the home of the International Atomic Energy Agency.” The United Nations’ atomic watchdog likely would be critical in any deal.

So clearly this is all about what the two negotiators, who have sidelined the State Department, Kushner and Witkoff, secretly reported to the felon. My guess is some progress was being made, clearly it was not what the president wanted. So, what ruled was his immediate need for a distraction after the failure of his State of the Union address to make any impact on his sagging poll numbers.

I have written often of the alternate universe Trump has us living in. I am just waiting for his MAGA cult to react to this. Will they still blindly follow everything he says, or will the Laura Loomers of the world finally say, “screw this, take care of us at home, do what you promised to make our lives better”. The first MAGA to say this was Marjorie Taylor Greene. Then Tucker Carlson added his slam against the felon. His PR flack, Karoline Leavitt, is getting confused by all the lies, recently saying “things are better than they were last year.” Clearly forgetting last year was 2025, and the felon was president for all except for 20 days of it, so is responsible for last year.

I am an optimist and believe our democracy will survive him, and his fascist cohorts’ blatant attacks. We won a revolution against one king, and survived a civil war, becoming even stronger as a united nation. We helped Europe defeat Hitler. I believe Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.) when he says the military will reject illegal orders. Orders that ask them to act against their fellow countrymen and women. I believe the American people will come to their senses before it’s too late. They will finally reject the POS in the White House, and the sycophants, and fascists, surrounding him in time to reclaim our nation for all the people.

Peter Rosenstein is a longtime LGBTQ rights and Democratic Party activist.

I recently lost my dog, Argo.

He was a pit bull, big, sweet, endlessly cuddly, and for 15 years he was my constant. The kind of presence you stop consciously noticing until they’re gone and the quiet hits you all at once. Pit bulls have a reputation. Argo never got the memo. He just loved people, completely and without condition, from the moment he met them until his last day.

I wasn’t prepared for what happened next.

My phone filled up. Instagram lit up. Texts came in from people I hadn’t heard from in months, in some cases years. Hugs from neighbors. Messages from colleagues. Condolences from people I’d lost touch with, some through nothing more than the slow drift of busy lives in a busy city, and some honestly through small tiffs and misunderstandings that neither of us ever bothered to resolve.

And sitting with all of that love pouring in, I found myself asking a question I wasn’t expecting: Why has it taken this long?

We do this in D.C. We get caught in our heads, our calendars, our ambitions. We let weeks turn into months. We let a small misunderstanding calcify into distance because nobody wants to be the first one to reach out, nobody wants to seem like they need something. We perform resilience so well that sometimes the people who care about us most don’t know we need them.

And then something breaks open, a loss, a moment of real vulnerability, and suddenly people show up. And you realize the connection was always there. It just needed permission.

Argo gave people permission. Even in dying, he did what he always did when he was alive. He brought people together.

I’ll be honest with you about where I’ve been lately. As I’ve climbed the entrepreneurial ladder, something quietly shifted. People stopped seeing Gerard. They started seeing a title, a resource, someone who could give them something or who owed them something. A character. Not a person. And when most of your day is spent inside other people’s problems and crises, you can start to feel it, a slow creep of cynicism that you don’t even notice until one day you realize you’ve gone numb.

And I’m not alone in that. Look around. We just watched innocent people die while those in power looked us in the face and called it something else. We watched people erupt over a 10-minute halftime performance like it was the greatest threat to our country. Everywhere you look there is something designed to make you angry, or exhausted, or both. Anger and numbness have become survival strategies. I understand it. I’ve lived it.

But here is what Argo reminded me.

The world is not what the loudest voices say it is. The world is what shows up when something real happens. And what showed up for me, after losing my sweet boy, was people. Caring, loving, present people who put down whatever they were doing to reach out to a friend. Some of them I hadn’t spoken to in too long. Some of them I’d had friction with. All of them showed up anyway.

That is the world. That is what it actually is underneath all the noise.

I think we’ve forgotten that. Or maybe we haven’t forgotten it, maybe we’re just so tired and overstimulated and battle-worn that we’ve stopped letting ourselves feel it. Because feeling it requires vulnerability, and vulnerability feels dangerous right now. It’s easier to scroll. It’s easier to stay mad. It’s easier to keep a wall up and call it wisdom.

Argo spent 15 years showing me a different way. He never met a stranger. He never held a grudge. He never saved his love for people who deserved it on paper. He just gave it, freely, every single time. Not a reward. Not a transaction. Just the most natural thing in the world.

Grief burns off everything that isn’t essential and leaves only what matters. What’s left for me is this: the world is full of good people. You may be surrounded by more of them than you know. And if you’ve gone numb, or angry, or so busy surviving that you’ve stopped connecting, I want you to know that the feeling can come back. It came back for me.

Reach out to someone today. Close a distance you’ve let grow. Tell someone they matter. Not because everything is perfect, but because connection is how we survive when it isn’t. Living disconnected, mad and closed off isn’t living at all. It’s a slower kind of dying.

Death came to teach me how to live. I hope this saves you some time.

Gerard Burley, also known as Coach G, is founder and CEO of Sweat DC.

-

National4 days ago

National4 days ago13 HIV/AIDS activists arrested on Capitol Hill

-

Photos5 days ago

Photos5 days agoPHOTOS: Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade

-

Florida3 days ago

Florida3 days agoFla. Senate passes ‘Anti-Diversity’ bill that could repeal local LGBTQ protections

-

Uganda4 days ago

Uganda4 days agoUgandan activist named Charles F. Kettering Foundation fellow