Books

Queer author Carmen Maria Machado draws raves for ‘Her Body’ short story collection

Writer says family storytelling tradition, collegiate experiences inform her fiction

Author Carmen Maria Machado says her love of reading and the storytelling tradition of her family deeply inform her work. (Photo courtesy Tom Storm Photography)

All fiction writers need imagination. Carmen Maria Machado’s is so vivid, she sometimes passes it on to her characters.

“Sometimes I sat on the porch and gave imaginary interviews to NPR personalities,” says the narrator of “The Resident,” a short story in Machado’s debut collection “Her Body and Other Parties.” “”When I write, I feel like I’m being hypnotized,’ I told Terry Gross. ‘It was at that moment I knew everything was going to change,’ I told Ira Glass.’”

For most writers, such daydreams remain mere fantasies. Few authors become literary superstars or suddenly find themselves under the spotlight on NPR. Yet this is what happened to Machado, a 31-year-old queer writer.

Her short story collection “Her Body and Other Parties” (Graywolf Press), released in October, has received the attention usually bestowed on the work of literary giants such as Toni Morrison or Michael Cunningham. “Parties” was a finalist for the National Book Award, the Kirkus Prize and the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize. It won the Bard Fiction Prize. It’s her first full-length work though she has had many of her stories published in various outlets.

“Parties” is unlike any previous short story collection. Women’s bodies, queerness and feminism pulsate through the tales in “Parties” from “Inventory” to “Difficult at Parties.” Yet the book isn’t didactic or the least bit doctrinaire. Like the horror movie “Get Out,” the stories pop with horror and comedy.

Women have joyous sex, even as people die worldwide from a virus spread by physical contact. A sexual assault survivor hears the inner thoughts of characters in porn. A novella “Especially Heinous: 272 Views of Law & Order: SVU,” is a piercing, but hilarious send up of “Law & Order: SVU” and its fascination with sexually traumatized women.

“The collection is that hallowed thing: an example of almost preposterous talent,” the Los Angeles Times said of “Her Body and Other Parties,” “that also encapsulates something vital but previously diffuse about the moment.”

Storytelling, Machado says during a Blade phone interview, is part of her family tradition. Her paternal grandfather came to the U.S. from Cuba; his wife was from Austria. They met as immigrants in New York. Her mother’s family is white.

“Storytelling, especially on the Cuban side of the family, is important,” Machado, an Allentown, Pa., native who now lives with her wife Val in Philadelphia, says. “My grandfather has dementia, but we can still recite stories back to him and he remembers.”

She incorporates that oral storytelling tradition in her work. Her love of reading and writing, as one might imagine, has deep roots.

As a child, Machado read voraciously. She went to the library and devoured books like candy, reading at breakneck speed, she says.

“All kids write stories. I wrote them and typed them out. I always loved the idea of being a writer.”

Machado sent her stories to publishers and authors. Her letters yielded no publishing offers, but, “my wife who works in publishing says that some delighted interns at the publishing houses must have loved my letters.”

To her surprise and delight, Machado heard back from Livia Bitton-Jackson, a Holocaust survivor and author of the memoir “I Have Lived a Thousand Years: Growing Up in the Holocaust.”

“In the book, Bitton-Jackson talked about how the poems she wrote were left behind when she was taken by the Nazis,” she says. “I wrote to her and asked what happened to her poems. One day, my mom, who was confused by it, said, ‘There’s a letter for you from Israel.’”

Bitton-Jackson told Machado that she didn’t get her poems back, but that she’d kept on writing.

“She asked me about myself,” she says. “It felt magical that a real person — a writer — wrote back to me.”

When she was young in the 1990s, Machado didn’t understand that she was queer.

“I had crushes on girls, but I didn’t think of it in that way. I didn’t have any framework,” she says. “I didn’t know anyone who was out and queer until I went to college.”

Machado graduated from American University in 2008 with a degree in visual media. During her years in Washington, she read the Blade as she was coming out.

“I thought, ‘Oh this is who I am,’” she says. “My parents were pretty chill, though they were a bit confused because I was lesbian/bi. They didn’t quite understand why I would date a guy, but they were great about it.”

Attitudes about being queer were different for some of Machado’s extended family.

“Some of them were very religious,” she says, “but I didn’t have to deal with a lot of that kind of nonsense. I feel extremely lucky.”

Machado went to college to study journalism, but quickly realized that wasn’t what she wanted to do, so she switched to literature and photography.

“I wanted to get loose with my sentences,” Machado says. “I didn’t have the blood thirst, the nose for news, to be a reporter.”

After graduating, Machado moved to Berkeley, Calif., working random jobs during the recession and enduring a bad break-up, which she says made her miserable. But she didn’t stop writing. A creative writing teacher, whom she calls “a lovely human being,” encouraged her to keep writing stories.

Her stint at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop from 2010-2012, where she earned a master’s degree, changed everything professionally for her.

“Suddenly, I was getting paid to be in grad school and write,” she says. “I didn’t have to worry about finding jobs. I had good health insurance. I could go to therapy and figure out my aesthetic.”

And, of course, her success with “Her Body” has helped fuel ongoing efforts. “House in Indiana,” a memoir about same-sex domestic violence is due in 2019.

“Same-sex violence isn’t talked about,” Machado says. “I wanted to talk about it.”

Kathi Wolfe, a writer and a poet, is a regular contributor to the Blade.

Books

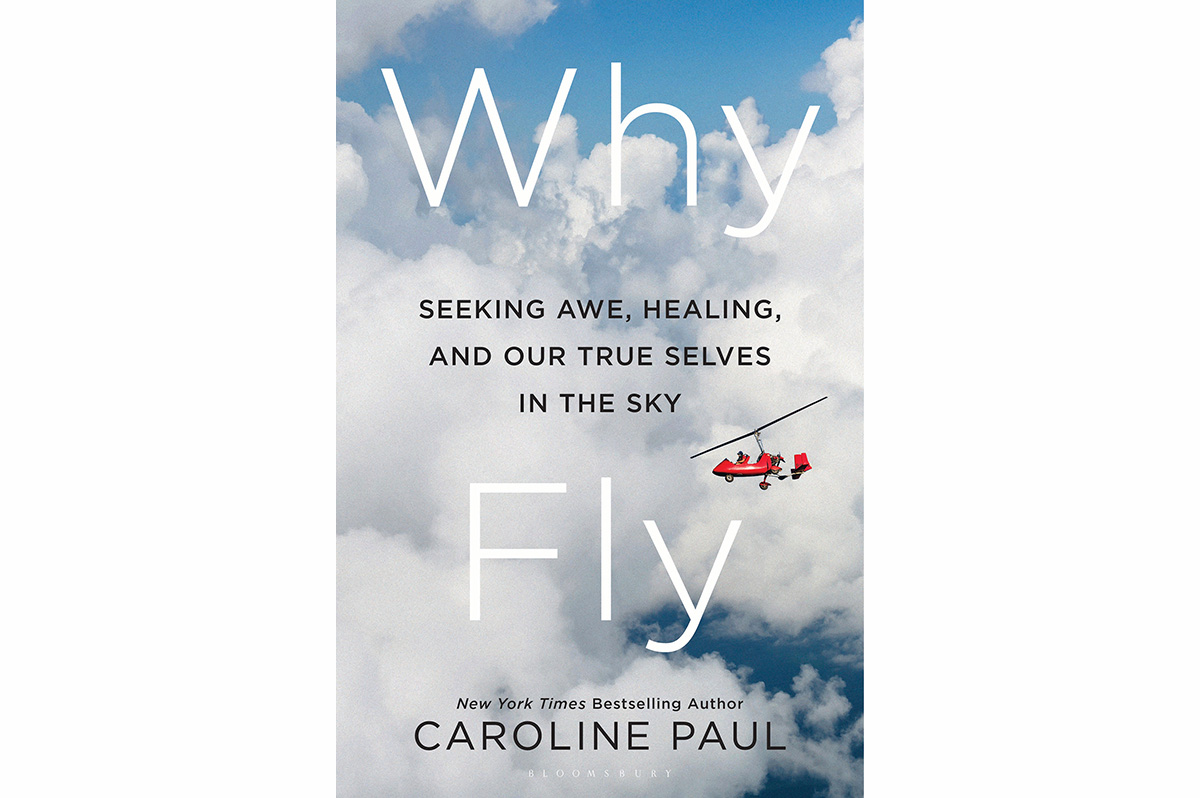

Love or fear flying you’ll devour ‘Why Fly’

New book chronicles a lifetime obsession with aircraft

‘Why Fly’

By Caroline Paul

c. 2026, Bloomsbury

$27.99/256 pages

Tray table folded up.

Check. Your seat is in the upright position, the airflow above your head is just the way you like it, and you’re ready to go. The flight crew is making final preparations. The lights are off and the plane is backing up. All you need now is “Why Fly” by Caroline Paul, and buckle up.

When she was very young, Paul was “obsessed” with tales of adventure, devouring accounts written by men of their derring-do. The only female adventure-seeker she knew about then was Amelia Earhart; later, she learned of other adventuresome women, including aviatrix Bessie Coleman, and Paul was transfixed.

Time passed; Paul grew up to create a life of adventure all her own.

Then, the year her marriage started to fracture, she switched her obsession from general exploits to flight.

Specifically, Paul loves experimental aircraft, some of which, like her “trike,” can be made from a kit at home. Others, like Woodstock, her beloved yellow gyrocopter, are major purchases that operate under different FAA rules. All flying has rules, she says, even if it seems like it should be as freewheeling as the birds it mimics.

She loves the pre-flight checklist, which is pure anticipation as well as a series of safety measures; if only a relationship had the same ritual. Paul loves her hangar, as a place of comfort and for flight in all senses of the word. She enjoys thinking about historic tales of flying, going back before the Wright Brothers, and including a man who went aloft on a lawn chair via helium-filled weather balloons.

The mere idea that she can fly any time is like a gift to Paul.

She knows a lot of people are terrified of flying, but it’s near totally safe: generally, there’s a one in almost 14 million chance of perishing in a commercial airline disaster – although, to Paul’s embarrassment and her dismay, it’s possible that both the smallest planes and the grandest loves might crash.

If you’re a fan of flying, you know what to do here. If you fear it, pry your fingernails off the armrests, take a deep breath, and head to the shelves. “Why Fly” might help you change your mind.

It’s not just that author Caroline Paul enjoys being airborne, and she tells you. It’s not that she’s honest in her explanations of being in love and being aloft. It’s the meditative aura you’ll get as you’re reading this book that makes it so appealing, despite the sometimes technical information that may flummox you between the Zen-ness. It’s not overwhelming; it mixes well with the history Paul includes, biographies, the science, heartbreak, and exciting tales of adventure and risk, but it’s there. Readers and romantics who love the outdoors, can’t resist a good mountain, and crave activity won’t mind it, though, not at all.

If you own a plane – or want to – you’ll want this book, too. It’s a great waiting-at-the-airport tale, or a tuck-in-your-suitcase-for-later read. Find “Why Fly” and you’ll see that it’s an upright kind of book.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

New book profiles LGBTQ Ukrainians, documents war experiences

Tuesday marks four years since Russia attacked Ukraine

Journalist J. Lester Feder’s new book profiles LGBTQ Ukrainians and their experiences during Russia’s war against their country.

Feder for “The Queer Face of War: Portraits and Stories from Ukraine” interviewed and photographed LGBTQ Ukrainians in Kyiv, the country’s capital, and in other cities. They include Olena Hloba, the co-founder of Tergo, a support group for parents and friends of LGBTQ Ukrainians, who fled her home in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha shortly after Russia launched its war on Feb. 24, 2022.

Russian soldiers killed civilians as they withdrew from Bucha. Videos and photographs that emerged from the Kyiv suburb showed dead bodies with their hands tied behind their back and other signs of torture.

Olena Shevchenko, chair of Insight, a Ukrainian LGBTQ rights group, wrote the book’s forward.

The book also profiles Viktor Pylypenko, a gay man who the Ukrainian military assigned to the 72nd Mechanized Black Cossack Brigade after the war began. Feder writes Pylypenko’s unit “was deployed to some of the fiercest and most important battles of the war.”

“The brigade was pivotal to beating Russian forces back from Kyiv in their initial attempt to take the capital, helping them liberate territory near Kharkiv and defending the front lines in Donbas,” wrote Feder.

Pylypenko spent two years fighting “on Ukraine’s most dangerous battlefields, serving primarily as a medic.”

“At times he felt he was living in a horror movie, watching tank shells tear his fellow soldiers apart before his eyes,” wrote Feder. “He held many men as they took their final breaths. Of the roughly one hundred who entered the unit with him, only six remained when he was discharged in 2024. He didn’t leave by choice: he went home to take care of his father, who had suffered a stroke.”

Feder notes one of Pylypenko’s former commanders attacked him online when he came out. Pylypenko said another commander defended him.

Feder also profiled Diana and Oleksii Polukhin, two residents of Kherson, a port city in southern Ukraine that is near the mouth of the Dnieper River.

Ukrainian forces regained control of Kherson in November 2022, nine months after Russia occupied it.

Diana, a cigarette vender, and Polukhin told Feder that Russian forces demanded they disclose the names of other LGBTQ Ukrainians in Kherson. Russian forces also tortured Diana and Polukhin while in their custody.

Polukhim is the first LGBTQ victim of Russian persecution to report their case to Ukrainian prosecutors.

Feder, who is of Ukrainian descent, first visited Ukraine in 2013 when he wrote for BuzzFeed.

He was Outright International’s Senior Fellow for Emergency Research from 2021-2023. Feder last traveled to Ukraine in December 2024.

Feder spoke about his book at Politics and Prose at the Wharf in Southwest D.C. on Feb. 6. The Washington Blade spoke with Feder on Feb. 20.

Feder told the Blade he began to work on the book when he was at Outright International and working with humanitarian groups on how to better serve LGBTQ Ukrainians. Feder said military service requirements, a lack of access to hormone therapy and documents that accurately reflect a person’s gender identity and LGBTQ-friendly shelters are among the myriad challenges that LGBTQ Ukrainians have faced since the war began.

“All of these were components of a queer experience of war that was not well documented, and we had never seen in one place, especially with photos,” he told the Blade. “I felt really called to do that, not only because of what was happening in Ukraine, but also as a way to bring to the surface issues that we’d had seen in Iraq and Syria and Afghanistan.”

Feder also spoke with the Blade about the war’s geopolitical implications.

Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2013 signed a law that bans the “promotion of homosexuality” to minors.

The 2014 Winter Olympics took place in Sochi, a Russian resort city on the Black Sea. Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine a few weeks after the games ended.

Russia’s anti-LGBTQ crackdown has continued over the last decade.

The Russian Supreme Court in 2023 ruled the “international LGBT movement” is an extremist organization and banned it. The Russian Justice Ministry last month designated ILGA World, a global LGBTQ and intersex rights group, as an “undesirable” organization.

Ukraine, meanwhile, has sought to align itself with Europe.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy after a 2021 meeting with then-President Joe Biden at the White House said his country would continue to fight discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. (Zelenskyy’s relationship with the U.S. has grown more tense since the Trump-Vance administration took office.) Zelenskyy in 2022 publicly backed civil partnerships for same-sex couples.

Then-Ukrainian Ambassador to the U.S. Oksana Markarova in 2023 applauded Kyiv Pride and other LGBTQ and intersex rights groups in her country when she spoke at a photo exhibit at Ukraine House in D.C. that highlighted LGBTQ and intersex soldiers. Then-Kyiv Pride Executive Director Lenny Emson, who Feder profiles in his book, was among those who attended the event.

“Thank you for everything you do in Kyiv, and thank you for everything that you do in order to fight the discrimination that still is somewhere in Ukraine,” said Markarova. “Not everything is perfect yet, but you know, I think we are moving in the right direction. And we together will not only fight the external enemy, but also will see equality.”

Feder in response to the Blade’s question about why he decided to write his book said he “didn’t feel” the “significance of Russia’s war against Ukraine” for LGBTQ people around the world “was fully understood.”

“This was an opportunity to tell that big story,” he said.

“The crackdown on LGBT rights inside Russia was essentially a laboratory for a strategy of attacking democratic values by attacking queer rights and it was one as Ukraine was getting closet to Europe back in 2013, 2014,” he added. “It was a strategy they were using as part of their foreign policy, and it was one they were using not only in Ukraine over the past decade, but around the world.”

Feder said Republicans are using “that same strategy to attack queer people, to attack democracy itself.”

“I felt like it was important that Americans understand that history,” he said.

Books

New book explores homosexuality in ancient cultures

‘Queer Thing About Sin’ explains impact of religious credo in Greece, Rome

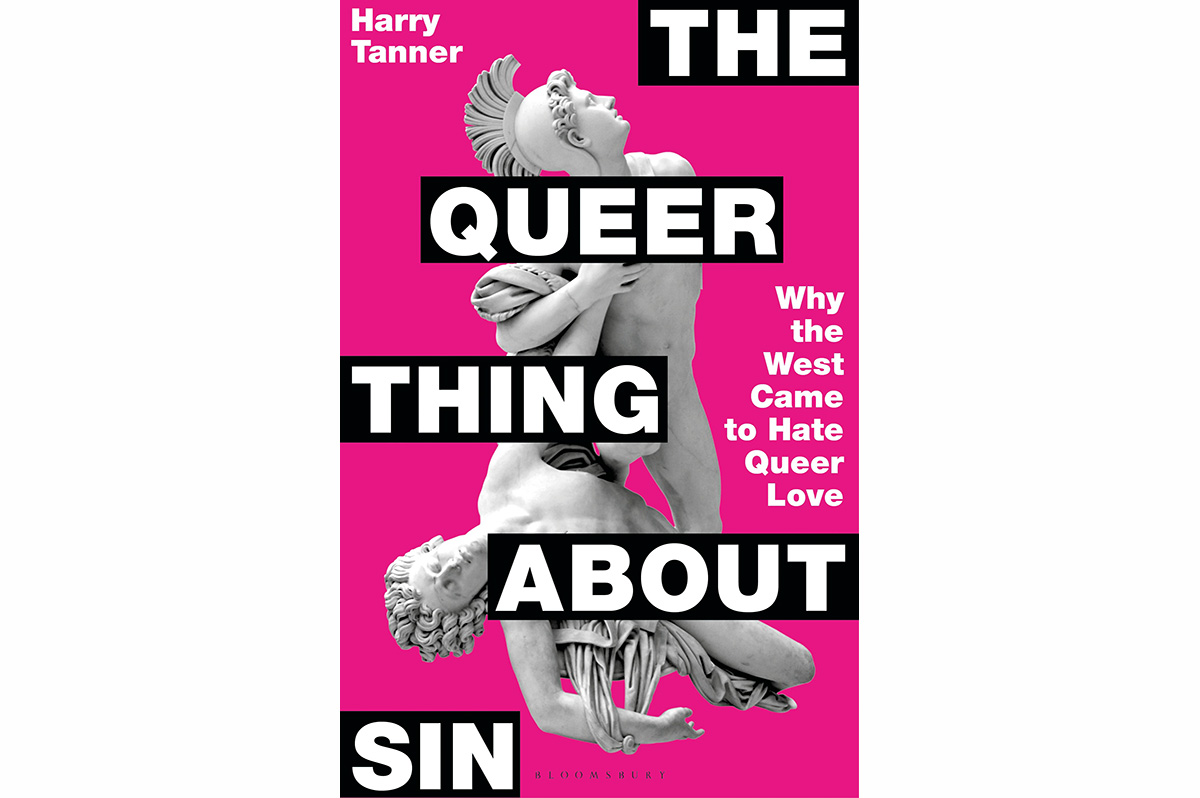

‘The Queer Thing About Sin’

By Harry Tanner

c.2025, Bloomsbury

$28/259 pages

Nobody likes you very much.

That’s how it seems sometimes, doesn’t it? Nobody wants to see you around, they don’t want to hear your voice, they can’t stand the thought of your existence and they’d really rather you just go away. It’s infuriating, and in the new book “The Queer Thing About Sin” by Harry Tanner, you’ll see how we got to this point.

When he was a teenager, Harry Tanner says that he thought he “was going to hell.”

For years, he’d been attracted to men and he prayed that it would stop. He asked for help from a lay minister who offered Tanner websites meant to repress his urges, but they weren’t the panacea Tanner hoped for. It wasn’t until he went to college that he found the answers he needed and “stopped fearing God’s retribution.”

Being gay wasn’t a sin. Not ever, but he “still wanted to know why Western culture believed it was for so long.”

Historically, many believe that older men were sexual “mentors” for teenage boys, but Tanner says that in ancient Greece and Rome, same-sex relationships were common between male partners of equal age and between differently-aged pairs, alike. Clarity comes by understanding relationships between husbands and wives then, and careful translation of the word “boy,” to show that age wasn’t a factor, but superiority and inferiority were.

In ancient Athens, queer love was considered to be “noble” but after the Persians sacked Athens, sex between men instead became an acceptable act of aggression aimed at conquered enemies. Raping a male prisoner was encouraged but, “Gay men became symbols of a depraved lack of self-control and abstinence.”

Later Greeks believed that men could turn into women “if they weren’t sufficiently virile.” Biblical interpretations point to more conflict; Leviticus specifically bans queer sex but “the Sumerians actively encouraged it.” The Egyptians hated it, but “there are sporadic clues that same-sex partners lived together in ancient Egypt.”

Says Tanner, “all is not what it seems.”

So you say you’re not really into ancient history. If it’s not your thing, then “The Queer Thing About Sin” won’t be, either.

Just know that if you skip this book, you’re missing out on the kind of excitement you get from reading mythology, but what’s here is true, and a much wider view than mere folklore. Author Harry Tanner invites readers to go deep inside philosophy, religion, and ancient culture, but the information he brings is not dry. No, there are major battles brought to life here, vanquished enemies and death – but also love, acceptance, even encouragement that the citizens of yore in many societies embraced and enjoyed. Tanner explains carefully how religious credo tied in with homosexuality (or didn’t) and he brings readers up to speed through recent times.

While this is not a breezy vacation read or a curl-up-with-a-blanket kind of book, “The Queer Thing About Sin” is absolutely worth spending time with. If you’re a thinking person and can give yourself a chance to ponder, you’ll like it very much.

-

India4 days ago

India4 days agoActivists push for better counting of transgender Indians in 2026 Census

-

Advice4 days ago

Advice4 days agoDry January has isolated me from my friends

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoCapital Pride reveals 2026 theme

-

National4 days ago

National4 days agoAfter layoffs at Advocate, parent company acquires ‘Them’ from Conde Nast