Books

‘Call Me By Your Name’ sequel ‘Find Me’ evocative but lacks original’s power

Aciman keeps readers waiting masochistically while introducing new characters

Unusually close father fixations, intense longing, the first flush of new romance that’s as scary as it is exciting, oh — and pretty much everybody here is bi. These are the major themes of “Find Me,” the sequel to “Call Me By Your Name.” Out Oct. 29, it continues the stories of the same-sex lovers Elio and Oliver that Andre Aciman introduced in his 2007 novel, memorably adapted into a 2017 movie with Timothee Chalamet and Armie Hammer.

I’m gonna stay pretty vague here and keep this as spoiler free as possible. If you want more on setting and premise, that’s easily available online. I went into this 100 percent blind and found the experience quite satisfying. “Call Me” director Luca Guadagino has said he’s planning a sequel of his own that would pick up a few years after the film (the book had an episodic final third not depicted in the movie) with Elio and Oliver navigating through the AIDS era. “Find Me” eschews that scenario altogether.

“Find Me” (**1/2 out of four) really takes its time gathering steam. I can’t necessarily say that’s a bad thing — one of “Call Me’s” biggest charms (in both book and film form) was its unusually languid pace, which so deftly captured the feel of a lazy Italian summer in which Elio and Oliver discovered each other. The pacing, though, worked much better in the earlier book as it was more suited to the timeline of the story. For Aciman to take his same good, ole’ time covering — as in the book’s first section — just a few days’ time, often feels laborious.

Not helping matters is how suddenly he’ll speed things up at whim. One particular same-sex romance in the middle section of the book dubbed “Cadenza” starts off with Aciman’s trademark detail in which no thought or action is deemed too fleeting or throwaway to not share. We’re treated to passages like: “… and then he asked if he could shampoo my hair, to which I said of course he could, and while the shampoo sat on my hair after he’d rubbed it in, I heard him wash himself, only then to feel his fingers rubbing and prodding my skull time and time again.”

That’s all fine and good — sensory detail can be powerful — but then just a few pages later: “Thursday that week we met again at nine at the same restaurant. Friday for lunch. And then for dinner as well. After breakfast that Saturday, he said he was going to drive to the country …” It’s such an extreme pick up of the pacing you almost feel literary whiplash.

Musical motifs form the book’s four sections — Tempo, Cadenza, Capriccio and Da Capo. Told in first person, it takes awhile in each section to figure out who’s speaking and where we are. And be ready to wait. I mean, really wait. Elio is first mentioned by name on page 107; Oliver is alluded to first on page 139. We first see his name on page 233.

As one plods through this leisurely pace, it’s always in the back of the mind whether or not Aciman will deliver a satisfying enough finale to have justified his long roundabouts. That’s, of course, up to each reader to decide, but I would have preferred not spending so much time in the lives and passions of new characters like Miranda (who figures heavily in Tempo, the longest section at a whopping 117 pages) and Michel, a central figure in “Cadenza.”

I was, at first, grateful to have been spared equally detailed prose about Micol, Oliver’s wife of many years, and how they ended up together. And yet, in retrospect, it would have yielded a bit more insight into Oliver, the more inscrutable of the central couple in “Call Me.” He ends up feeling like an afterthought here. Yes, we do get inside his head a bit in Capriccio and Da Capo, but it feels underdeveloped. In Cadenza, Aciman spends dozens of pages detailing Elio (a pianist) cracking a musical mystery (he’s given a handwritten score of murky origins). It’s mildly involving and ends up having some poignance, but ultimately factors — as is common with these types of red herring plot devices — way less in the grand scheme of the story than you’d think considering the attention it gets.

Aciman’s biggest failure here is his inability to differentiate his characters enough as they navigate the throes and blushes of new love. Told always in first person, they narrate things like, “we were staring at each other, and yet neither of us was saying anything. I knew that if I uttered another word I would break the spell, so we sat there, silent and staring, silent and staring, as if she too did not want to lift the spell.” By the end of the book, we’ve been treated to three rounds of this sort of thing from three different perspectives but the voices aren’t distinct enough to justify such poring over these mini-moments.

One might argue that’s the point — Aciman is noting how similar these mating rituals, this flirting is across the board, male or female, gay (more like bi) or straight. But he introduces, then tosses aside so cavalierly such major characters in his story while making us wait, almost masochistically, to discover the fate of Elio and Oliver, it ends up feeling more like a long trip around Robin Hood’s barn than the insightful dissection of human emotion he clearly intends it to be.

In fairness, do these things ever really work? One thinks, of course, of everything from the recent “The Testaments” (the sequel to “The Handmaid’s Tale”) to “Go Set a Watchman” (sequel to “To Kill a Mockingbird”). Are these projects ever terribly satisfying? What would that even look like in Elio and Oliver’s world? Do we want them together setting up house with a white picket fence? We’d hate him if he’d killed one of them off. What does one do with this conundrum?

Aciman has made a noble effort and the book is engrossing, even at his pace, which is actually saying something. But ultimately too much time is spent on rabbit trails with the goods way too rushed over in the final section (Da Capo is a mere 13 pages) to prove effective, much less as shatteringly evocative as “Call Me.”

Books

Embracing the chaos can be part of the fun

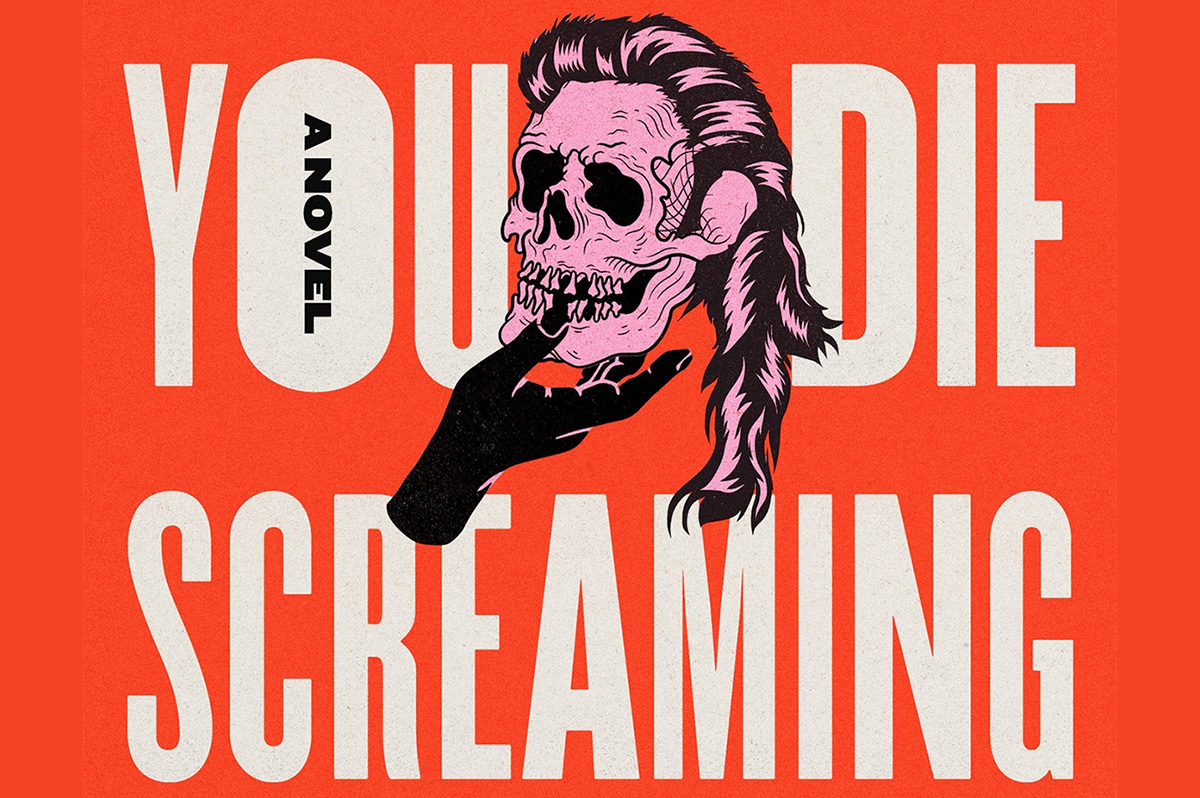

‘Make Sure You Die Screaming’ offers many twists and turns

‘Make Sure You Die Screaming’

By Zee Carlstrom

c.2025, Random House

$28/304 pages

Sometimes, you just want to shut the door and forget what’s on the other side.

You could just wipe it from your memory, like it didn’t occur. Or create an alternate universe where bad things never happen to you and where, as in the new novel “Make Sure You Die Screaming” by Zee Carlstrom, you can pretend not to care.

Their mother called them “Holden,” but they’d stopped using that name and they hadn’t decided what to use now. What do you call an alcoholic, queer, pessimistic former ad executive who’s also “The World’s First Honest White Man,” although they no longer identify as a man? It’s a conundrum that they’ll have to figure out soon because a cop’s been following them almost since they left Chicago with Yivi, their psychic new best friend.

Until yesterday, they’d been sleeping on a futon in some lady’s basement, drinking whatever Yivi mixed, and trying not to think about Jenny. They killed Jenny, they’re sure of it. And that’s one reason why it’s prudent to freak out about the cop.

The other reason is that the car they’re driving was stolen from their ex-boyfriend who probably doesn’t know it’s gone yet.

This road trip wasn’t exactly well-planned. Their mother called, saying they were needed in Arkansas to find their father, who’d gone missing so, against their better judgment, they packed as much alcohol as Yivi could find and headed south. Their dad had always been unique, a cruel man, abusive, intractable; he suffered from PTSD, and probably another half-dozen acronyms, the doctors were never sure. They didn’t want to find him, but their mother called…

It was probably for the best; Yivi claimed that a drug dealer was chasing her, and leaving Chicago seemed like a good thing.

They wanted a drink more than anything. Except maybe not more than they wanted to escape thoughts of their old life, of Jenny and her death. And the more miles that passed, the closer they came to the end of the road.

If you think there’s a real possibility that “Make Sure You Die Screaming” might run off the rails a time or three, you’re right. It’s really out there, but not always in a bad way. Reading it, in fact, is like squatting down in a wet, stinky alley just after the trash collector has come: it’s filthy, dank, and profanity-filled. Then again, it’s also absurd and dark and philosophical, highly enjoyable but also satisfying and a little disturbing; Palahniuk-like but less metaphoric.

That’s a stew that works and author Zee Carlstrom stirs it well, with characters who are sardonic and witty while fighting the feeling that they’re unredeemable losers – which they’re not, and that becomes obvious.

You’ll see that all the way to one of the weirdest endings ever.

Readers who can withstand this book’s utter confusion by remembering that chaos is half the point will enjoy taking the road trip inside “Make Sure You Die Screaming.”

Just buckle up tight. Then shut the door, and read.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

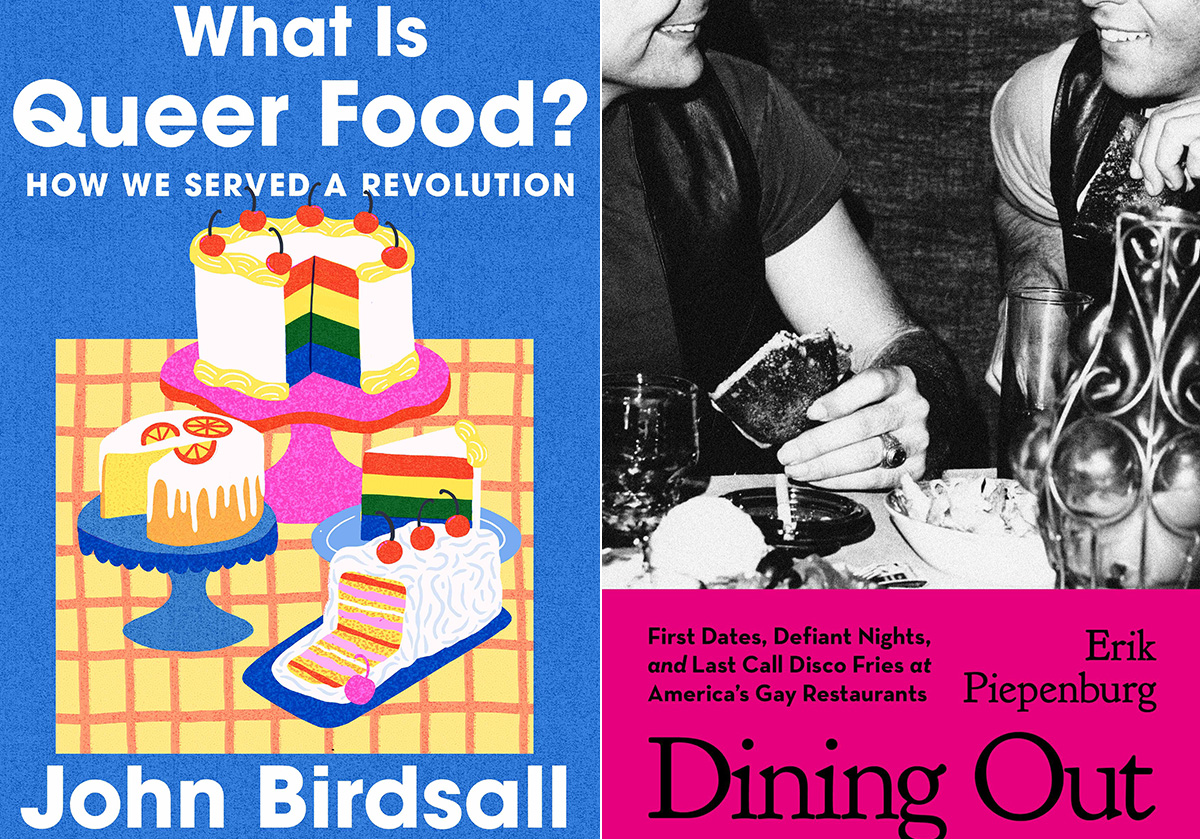

Two new books on dining out LGBTQ-style

Visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers

‘What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution’

By John Birdsall

c.2025, W.W. Norton

$29.99/304 pages

‘Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants’

By Erik Piepenburg

c.2025, Grand Central

$30/352 pages

You thought a long time about who sits where.

Compatibility is key for a good dinner party, so place cards were the first consideration; you have at least one left-hander on your guest list, and you figured his comfort into your seating chart. You want the conversation to flow, which is music to your ears. And you did a good job but, as you’ll see with these two great books on dining LGBTQ-style, it’s sometimes not who sits where, but whose recipes were used.

When you first pick up “What is Queer Food?” by John Birdsall, you might miss the subtitle: “How We Served a Revolution.” It’s that second part that’s important.

Starting with a basic gay and lesbian history of America, Birdsall shows how influential and (in)famous 20th century queer folk set aside the cruelty and discrimination they received, in order to live their lives. They couldn’t speak about those things, he says, but they “sat down together” and they ate.

That suggested “a queer common purpose,” says Birdsall. “This is how who we are, dahling, This is how we feed our own. This is how we stay alive.”

Readers who love to cook, bake or entertain, collect cookbooks, or use a fork will want this book. Its stories are nicely served, they’re addicting, and they may send you in search of cookbooks you didn’t know existed.

Sometimes, though, you don’t want to be stuck in the kitchen, you want someone else to bring the grub. “Dining Out” by Erik Piepenburg is an often-nostalgic, lively look at LGBTQ-friendly places to grab a meal – both now and in the past.

In his introduction, Piepenburg admits that he’s a journalist, “not a historian or an academic,” which colors this book, but not negatively. Indeed, his journeys to “gay restaurants” – even his generous and wide-ranging definitions of the term – happily influence how he presents his narrative about eateries and other establishments that have fed protesters, nourished budding romances, and offered audacious inclusion.

Here, there are modern tales of drag lunches and lesbian-friendly automats that offered “cheap food” nearly a century ago. You’ll visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers on holidays. Stepping back, you’ll read about AIDS activism at gay-friendly establishments, and mostly gay neighborhood watering holes. Go underground at a basement bar; keep tripping and meet proprietors, managers, customers and performers. Then take a peek into the future, as Piepenburg sees it.

The locales profiled in “Dining Out” may surprise you because of where they can be found; some of the hot-spots practically beg for a road trip.

After reading this book, you’ll feel welcome at any of them.

If these books don’t shed enough light on queer food, then head to your favorite bookstore or library and ask for help finding more. The booksellers and librarians there will put cookbooks and history books directly in your hands, and they’ll help you find more on the history and culture of the food you eat. Grab them and you’ll agree, they’re pretty tasty reads.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

You’re going to be on your feet a lot this month.

Marching in parades, dancing in the streets, standing up for people in your community. But you’re also likely to have some time to rest and reflect – and with these great new books, to read.

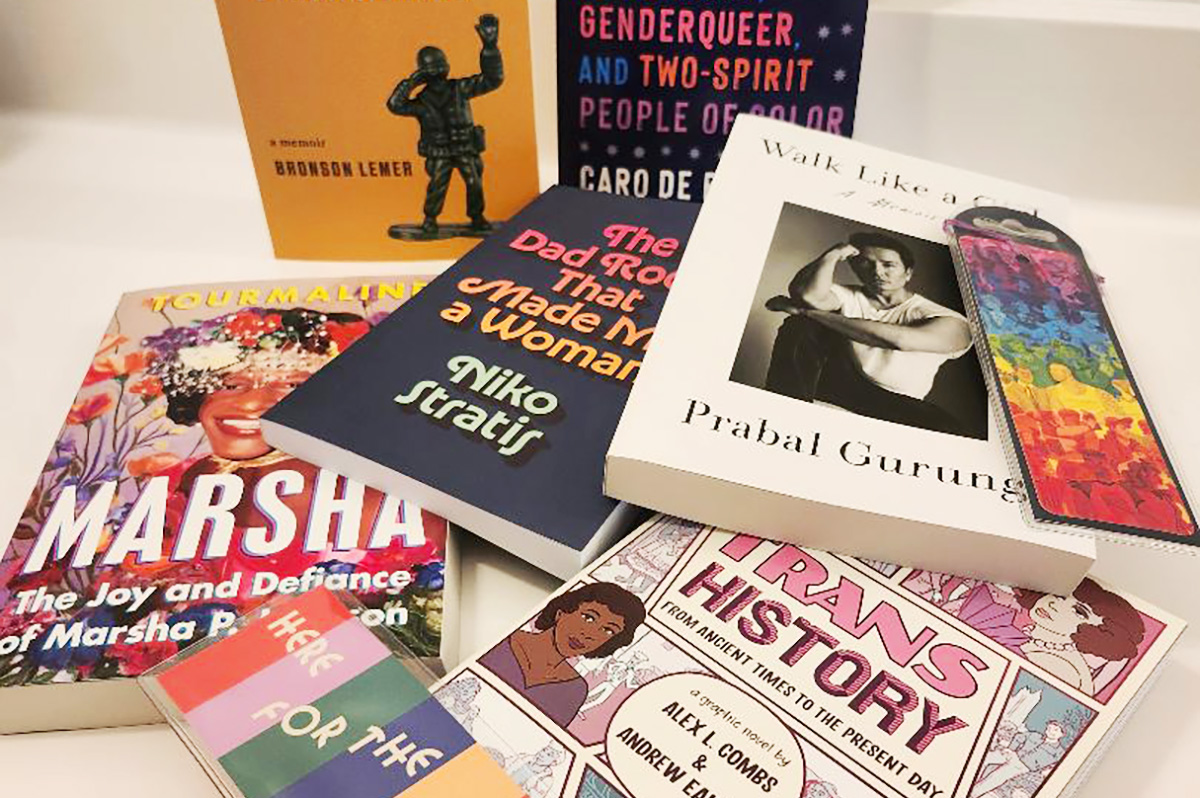

First, dip into a biography with “Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson” by Tourmaline (Tiny Rep Books, $30), a nice look at an icon who, rumor has it, threw the brick that started a revolution. It’s a lively tale about Marsha P. Johnson, her life, her activism before Stonewall and afterward. Reading this interesting and highly researched history is a great way to spend some time during Pride month.

For the reader who can’t live without music, try “The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman” by Niko Stratis (University of Texas Press, $27.95), the story of being trans, searching for your place in the world, and finding it in a certain comfortable genre of music. Also look for “The Lonely Veteran’s Guide to Companionship” by Bronson Lemer (University of Wisconsin Press, $19.95), a collection of essays that make up a memoir of this and that, of being queer, basic training, teaching overseas, influential books, and life.

If you still have room for one more memoir, try “Walk Like a Girl” by Prabal Gurung (Viking, $32.00). It’s the story of one queer boy’s childhood in India and Nepal, and the intolerance he experienced as a child, which caused him to dream of New York and the life he imagined there. As you can imagine, dreams and reality collided but nonetheless, Gurung stayed, persevered, and eventually became an award-winning fashion designer, highly sought by fashion icons and lovers of haute couture. This is an inspiring tale that you shouldn’t miss.

No Pride celebration is complete without a history book or two.

In “Trans History: From Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Alex L. Combs & Andrew Eakett ($24.99, Candlewick Press), you’ll see that being trans is something that’s as old as humanity. One nice part about this book: it’s in graphic novel form, so it’s lighter to read but still informative. Lastly, try “So Many Stars: An Oral History of Trans, Nonbinary, Genderqueer, and Two-Spirit People of Color” by Caro De Robertis (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. $32.00) a collection of thoughts, observations, and truths from over a dozen people who share their stories. As an “oral history,” you’ll be glad to know that each page is full of mini-segments you can dip into anywhere, read from cover to cover, double-back and read again. It’s that kind of book.

And if these six books aren’t enough, if they don’t quite fit what you crave now, be sure to ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for help. There are literally tens of thousands of books that are perfect for Pride month and beyond. They’ll be able to determine what you’re looking for, and they’ll put it directly in your hands. So stand up. March. And then sit and read.

-

Virginia2 days ago

Virginia2 days agoDefying trends, new LGBTQ center opens in rural Winchester, Va.

-

South Africa5 days ago

South Africa5 days agoLesbian feminist becomes South African MP

-

Travel3 days ago

Travel3 days agoManchester is vibrant tapestry of culture, history, and Pride

-

Opinions3 days ago

Opinions3 days agoUSAID’s demise: America’s global betrayal of trust with LGBTQ people