Books

Nonbinary poet unmasks society’s gender expectations in new collection

Karen Poppy’s ‘Diving At The Lip Of The Water’ debuts next week

“I started to compose poetry around the age of three – before I could even write,” poet Karen Poppy, 47, told the Blade in a telephone interview. “My Mom would write my poems down.”

“I had the good fortune,” added Poppy, whose first, full-length poetry collection “Diving At The Lip Of The Water” will be out from Beltway Editions, a Washington, D.C. area press, on May 1, “My Mom read poetry to me. The first poem was about a nightingale. Maybe she read Keats to me.” (John Keats was the 19th century Romantic poet who wrote “Ode to a Nightingale.”)

Poppy has written a book “that will rough a reader up and then wrap their scraps in silk,” poet Francesca Bell has said of “Diving At The Lip of The Water.” For Poppy, who identifies as queer, nonbinary, lesbian and an artist, coming out has been a lifelong process. “I’ve come out many times in many ways,” Poppy, who grew up in Foster City, Calif., and now lives in the San Francisco Bay area, said.

April is National Poetry Month. In every month, Poppy thinks often of Walt Whitman, one of the United States’ greatest poets. Thought by many to be queer, Whitman, a nurse in Washington, D.C. during the Civil War, is best known for his groundbreaking work “Leaves of Grass.”

Whitman comes to mind to Poppy when she talks about her identity. “As an artist,” Poppy said in reference to how she identifies, “I’m everyone and everything.”

When Whitman talks about the self containing “multitudes,” “He’s not just speaking of individuals,” Poppy said, “he’s saying that poets-artists enter into everything.”

“As an artist – a poet,” Poppy said, “I don’t like to be put into boxes.”

Poppy celebrates Whitman’s creative spirit, refusal to have limitations placed on him and, what she called, “his joyous experience of limitlessness and connectivity with everything.”

As a young child, Poppy sensed that she was different. “I knew very early on,” she said, “I wanted to be like my mother and my father.”

She wanted to be glam like her mom. “My Mom’s family’s nickname for Mom was Miss America,” Poppy said.

She wore her Dad’s leather jacket, cowboy hat and cowboy boots. “Early on, I got in trouble for trying to smoke a cigarette,” Poppy said, “I put it in the wrong way. I was lucky I didn’t burn my mouth!”

“I cut my mouth, trying to shave as a toddler,” she added, “I was already creating my own gender identity.”

At a time, when people were far less out and proud than now, Poppy crushed on her girl babysitters. “In kindergarten, I got in trouble with my best friend at the time,” she said, “because I told her that I was interested in her physically.”

“I think she was very kind about it,” Poppy added.

That same year, Poppy was reprimanded by her teacher for kissing a boy. “The boy and I were in line waiting to go back to the classroom,” she said, “he kissed me back.”

During that era, Poppy didn’t have the words to name or describe her feelings. “I have a gay cousin who’s older than me,” she said, “and a lesbian aunt. But because they weren’t exactly the way I am, I didn’t realize I was queer, too.”

In Foster City, when she was growing up, people didn’t talk openly about being queer. “We talked about it in euphemisms and negatively,” Poppy said.

A poem is never just the story of what happened or the recitation of fact, poet Sheila Black, a 2012 Witter Bynner Fellow, said in an email to the Blade.

Poppy’s poetry, like that of many poets, at times, channels her life. Though, it’s not autobiographical in a literal or linear way. Like Whitman’s work, it contains multitudes from individual and collective experience.

Her searing, moving collection “Diving At The Lip Of The Water,” unmasks society’s gender expectations and family systems. Poppy’s poem, “No One was Gay Back Then,” draws us into what it’s like to have to hide your sexuality. “We used to make fun of you/You, making out with Michael/in the grass. 5th grade recess,” the poem begins.

“Michael liked Matt. So in 5th grade,” Poppy writes in the poem, “already seeking cover-ups/Trying to convince everyone and ourselves./Our small town. No one was gay back then.”

As a tween, Poppy not only realized she was queer (though she didn’t have the word for it); she knew where she wanted to go to college. Poppy was determined to go to Smith College because Sylvia Plath went there.

“When I was 12, I started to read Sylvia Plath,” Poppy said. “Plath has been a profound influence on me throughout my life.”

“Because of her fearlessness in speaking her truth,” Poppy added, “and her high level of poetic virtuosity.”

Poppy’s dream came true. She earned a bachelor’s degree from Smith College in Comparative Literature and Spanish in 1998.

At Smith, Poppy began to come out about her identity. But, there were pressures. “I was pressured into cutting my hair short,” she said, “the feeling was if I kept my hair long, I wasn’t a dyke.”

Poppy cut her hair. “I did cry,” she said, “there was a pressure to conform to a certain aesthetic. You had to be super femme or butch.”

It was another box that she had a hard time escaping from. “I realized boxes are not for me,” Poppy said.

She wasn’t sure what she wanted to do after she graduated from Smith. After a short stint as a chef apprentice, Poppy could tell that being a chef for the long term wasn’t for her.

Like most poets, Poppy knew being a bard rarely brings financial stability. “I wanted to have security and I wanted to help people,” Poppy said.

“I went to law school and studied international law,” she said, “A lot of my early focus was on immigration and helping refugees.”

Poppy graduated from UC Hastings College of the Law (now known as UC College of the Law, San Francisco) in 2003 with a J.D. degree in international law.

Today, Poppy works for The Hartford in the area of workers’ compensation.

Poppy kept writing from her childhood into her 20s. “But then, somebody said something really cruel about my writing,” she said. “The ridicule chilled my creativity.”

For 17 years, because of this cruelty, she didn’t write. “I was in a creative silence,” Poppy said.

A traumatic event compelled her to go back to writing.

Since 2017, when her creativity was restarted, Poppy’s poetry has been published in literary journals, anthologies as well as the chapbooks “Crack Open/Emergency,” “Our Own Beautiful Brutality” and “Every Possible Thing.” She’s written three unpublished novels and short stories.

One of her writing projects is Whitmanesque in its intersections of identities.

Poppy is working on an opera libretto. “It takes place when Handel [the German-British Baroque composer] was alive,” she said.

It’s about a merboy who’s washed to shore. He’s young, Black and queer.

“A family takes him in,” Poppy said, “they want to make him a form of income.”

The family forces the merboy to become a castrato, Poppy said, “they make him wear a mask to hide his dark skin. When he’s older and has a relationship with a man, he has to be closeted.”

Poppy is looking for a composer to work with her on her libretto. If you’re interested, contact her through her website karenpoppy.com.

Poppy’s interest in immigrants is personal as well as professional. Poppy is Jewish. Some of her family were murdered in the Holocaust. “Others in my family left Europe before the Holocaust because of pogroms and poverty,” she said.

When her family came to the United States in the early 1900s, they were “very poor,” Poppy said.

Her paternal grandmother, Poppy said, told her to make sure her son always had food, “because hunger would make his stomach hurt.”

We’ve come to see that the American dream is in many ways an illusion, Poppy said. It’s not accessible to all, and it’s slipping away.

“Elizabeth/The fifth of ten children/Who crossed the border, then/Still a child/,” Poppy writes in her poem “Elizabeth,” “Only sixteen and wanting to stay alive/To be the breath that survived.”

Poppy worries about the rise of anti-Semitism. “It comes in waves,” she said. “We have to remind each other to make sure it never happens again.”

It’s important for artists to take care of themselves, Poppy said. To get enough rest between creative projects. To be an athlete. So their minds and spirits can be in top form.

Poppy does yoga and loves to run. “A poem is a short lap,” she said, “writing a novel is like long distance open water swimming.”

“We write out of our humanity,” Poppy added.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

New book explores homosexuality in ancient cultures

‘Queer Thing About Sin’ explains impact of religious credo in Greece, Rome

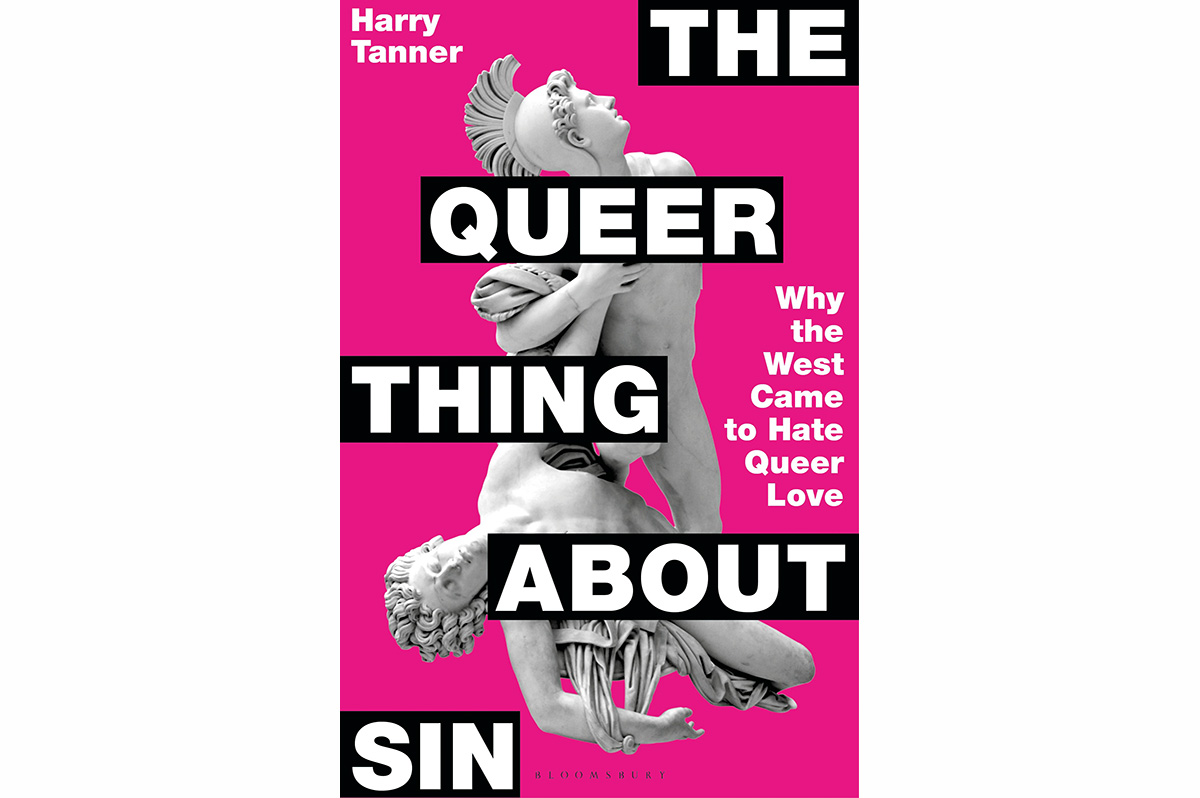

‘The Queer Thing About Sin’

By Harry Tanner

c.2025, Bloomsbury

$28/259 pages

Nobody likes you very much.

That’s how it seems sometimes, doesn’t it? Nobody wants to see you around, they don’t want to hear your voice, they can’t stand the thought of your existence and they’d really rather you just go away. It’s infuriating, and in the new book “The Queer Thing About Sin” by Harry Tanner, you’ll see how we got to this point.

When he was a teenager, Harry Tanner says that he thought he “was going to hell.”

For years, he’d been attracted to men and he prayed that it would stop. He asked for help from a lay minister who offered Tanner websites meant to repress his urges, but they weren’t the panacea Tanner hoped for. It wasn’t until he went to college that he found the answers he needed and “stopped fearing God’s retribution.”

Being gay wasn’t a sin. Not ever, but he “still wanted to know why Western culture believed it was for so long.”

Historically, many believe that older men were sexual “mentors” for teenage boys, but Tanner says that in ancient Greece and Rome, same-sex relationships were common between male partners of equal age and between differently-aged pairs, alike. Clarity comes by understanding relationships between husbands and wives then, and careful translation of the word “boy,” to show that age wasn’t a factor, but superiority and inferiority were.

In ancient Athens, queer love was considered to be “noble” but after the Persians sacked Athens, sex between men instead became an acceptable act of aggression aimed at conquered enemies. Raping a male prisoner was encouraged but, “Gay men became symbols of a depraved lack of self-control and abstinence.”

Later Greeks believed that men could turn into women “if they weren’t sufficiently virile.” Biblical interpretations point to more conflict; Leviticus specifically bans queer sex but “the Sumerians actively encouraged it.” The Egyptians hated it, but “there are sporadic clues that same-sex partners lived together in ancient Egypt.”

Says Tanner, “all is not what it seems.”

So you say you’re not really into ancient history. If it’s not your thing, then “The Queer Thing About Sin” won’t be, either.

Just know that if you skip this book, you’re missing out on the kind of excitement you get from reading mythology, but what’s here is true, and a much wider view than mere folklore. Author Harry Tanner invites readers to go deep inside philosophy, religion, and ancient culture, but the information he brings is not dry. No, there are major battles brought to life here, vanquished enemies and death – but also love, acceptance, even encouragement that the citizens of yore in many societies embraced and enjoyed. Tanner explains carefully how religious credo tied in with homosexuality (or didn’t) and he brings readers up to speed through recent times.

While this is not a breezy vacation read or a curl-up-with-a-blanket kind of book, “The Queer Thing About Sin” is absolutely worth spending time with. If you’re a thinking person and can give yourself a chance to ponder, you’ll like it very much.

Books

‘The Director’ highlights film director who collaborated with Hitler

But new book omits gay characters, themes from Weimar era

‘The Director’

By Daniel Kehlmann

Summit Books, 2025

Garbo to Goebbels, Daniel Kehlmann’s historical novel “The Director” is the story of Austrian film director G.W. Pabst (1885-1967) and his descent down a crooked staircase of ambition into collaboration with Adolph Hitler’s film industry and its Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. Kehlmann’s historical fiction is rooted in the world of Weimar German filmmaking and Nazi “Aryan” cinema, but it is a searing story for our challenging time as well.

Pabst was a legendary silent film director from the Weimar Republic’s Golden Era of filmmaking. He “discovered” Greta Garbo; directed silent screen star Louise Brooks; worked with Hitler’s favored director Leni Riefenstahl (“Triumph of the Will”); was a close friend of Fritz Lang (“Metropolis”); and lived in Hollywood among the refugee German film community, poolside with Billy Wilder (“Some Like it Hot”) and Fred Zinnemann (“High Noon”) — both of whose families perished in the Holocaust.

Yet, Pabst left the safety of a life and career in Los Angeles and returned to Nazi Germany in pursuit of his former glory. He felt the studios were giving him terrible scripts and not permitting him to cast his films as he wished. Then he received a signal that he would be welcome in Nazi Germany. He was not Jewish.

Kehlmann, whose father at age 17 was sent to a concentration camp and survived, takes the reader inside each station of Pabst’s passage from Hollywood frustration to moral ruin, making the incremental compromises that collectively land him in the hellish Berlin office of Joseph Goebbels. In an unforgettably phantasmagoric scene, Goebbels triples the stakes with the aging filmmaker, “Consider what I can offer you….a concentration camp. At any time. No problem,” he says. “Or what else…anything you want. Any budget, any actor. Any film you want to make.” Startled, paralyzed and seduced by the horror of such an offer, Pabst accepts not with a signature but a salute: “Heil Hitler,” rises Pabst. He’s in.

The novel develops the disgusting world of compromise and collaboration when Pabst is called in to co-direct a schlock feature with Hitler’s cinematic soulmate Riefenstahl. Riefenstahl, the “Directress” is making a film based on the Fuhrer’s favorite opera. She is beautiful, electric and beyond weird playing a Spanish dancer who mesmerizes the rustic Austrian locals with her exotic moves. The problem is scores of extras will be needed to surround and desire Fraulein Riefenstahl. Mysteriously, the “extras” arrive surprising Pabst who wonders where she had gotten so many young men when almost everyone was on the front fighting the war. The extras were trucked in from Salzburg, he is told, “Maxglan to be precise.” He pretends not to hear. Maxglan was a forced labor camp for “racially inferior” Sinti and Roma gypsies, who will later be deported from Austria and exterminated. Pabst does not ask questions. All he wants is their faces, tight black and white shots of their manly, authentic, and hungry features. “You see everything you don’t have,” he exhorts the doomed prisoners to emote for his camera. Great art, he believes, is worth the temporal compromises and enticements that Kehlmann artfully dangles in the director’s face. And it gets worse.

One collaborates in this world with cynicism born of helpless futility. In Hollywood, Pabst was desperate to develop his own pictures and lure the star who could bless his script, one of the thousands that come their way. Such was Greta Garbo, “the most beautiful woman in the world” she was called after being filmed by Pabst in the 1920s. He shot her close-ups in slow motion to make her look even more gorgeous and ethereal. Garbo loved Pabst and owed him much, but Kehlmann writes, “Excessive beauty was hard to bear, it burned something in the people around it, it was like a curse.”

Garbo imagined what it would be like to be “a God or archangel and constantly feel the prayers rising from the depths. There were so many, there was nothing to do but ignore them all.” Fred Zinnemann, later to direct “High Noon”, explains to his poolside guest, “Life here (in Hollywood) is very good if you learn the game. We escaped hell, we ought to be rejoicing all day long, but instead we feel sorry for ourselves because we have to make westerns even though we are allergic to horses.”

The texture of history in the novel is rich. So, it was disappointing and puzzling there was not an original gay character, a “degenerate” according to Nazi propaganda, portrayed in Pabst’s theater or filmmaking circles. From Hollywood to Berlin to Vienna, it would have been easy to bring a sexual minority to life on the set. Sexual minorities and gender ambiguity were widely presented in Weimar films. Indeed, in one of Pabst’s films “Pandora’s Box” starring Louise Brooks there was a lesbian subplot. In 1933, when thousands of books written by, and about homosexuals, were looted and thrown onto a Berlin bonfire, Goebbels proclaimed, “No to decadence and moral corruption!” The Pabst era has been de-gayed in “The Director.”

“He had to make films,” Kehlmann cuts to the chase with G.W. Pabst. “There was nothing else he wanted, nothing more important.” Pabst’s long road of compromise, collaboration and moral ruin was traveled in small steps. In a recent interview Kehlmann says the lesson is to “not compromise early when you still have the opportunity to say ‘no.’” Pabst, the director, believed his art would save him. This novel does that in a dark way.

(Charles Francis is President of the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., and author of “Archive Activism: Memoir of a ‘Uniquely Nasty’ Journey.”)

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

‘The Vampire Chronicles’ inspire LGBTQ people around the world

AMC’s ‘Interview with the Vampire’ has brought feelings back to live

Four kids pedaled furiously, their bicycles wobbling over cracked pavement and uneven curbs. Laughter and shouted arguments about which mystical creature could beat which echoed down the quiet street. They carried backpacks stuffed with well-worn paperbacks — comic books and fantasy novels — each child lost in a private world of monsters, magic, and secret codes. The air hummed with the kind of adventure that exists only at the edge of imagination, shaped by an imaginary world created in another part of the planet.

This is not a description of “Stranger Things,” nor of an American suburb in the 1980s. This is a small Russian village in the early 2000s — a place without paved roads, where most houses had no running water or central heating — where I spent every summer of my childhood. Those kids were my friends, and the world we were obsessed with was “The Vampire Chronicles” by Anne Rice.

We didn’t yet know that one of us would soon come out as openly bi, or that another — me — would become an LGBTQ activist. We were reading our first queer story in Anne Rice’s books. My first queer story. It felt wrong. And it felt extremely right. I haven’t accepted that I’m queer yet, but the easiness queerness was discussed in books helped.

Now, with AMC’s “Interview with the Vampire,” starring Jacob Anderson as Louis de Pointe du Lac — a visibly human, openly queer, aching vampire — and Sam Reid as Lestat de Lioncourt, something old has stirred back to life. Louis remains haunted by what he is and what he has done. Lestat, meanwhile, is neither hero nor villain. He desires without apology, and survives without shame.

I remember my bi friend — who was struggling with a difficult family — identifying with Lestat. Long before she came out, I already saw her queerness reflected there. “The Vampire Chronicles” allowed both of us to come out, at least to each other, with surprising ease despite the queerphobic environment.

While watching — and rewatching — the series over this winter holiday, I kept thinking about what this story has meant, and still means, for queer youth and queer people worldwide. Once again, this is not just about “the West.” I read comments from queer Ukrainian teenagers living under bombardment, finding joy in the show. I saw Russian fans furious at the absurdly censored translation by Amediateca, which rendered “boyfriend” as “friend” or even “pal,” turning the central relationship between two queer vampires into near-comic nonsense. Mentions of Putin were also erased from the modern adaptation — part of a broader Russian effort to eliminate queer visibility and political critique altogether.

And yet, fans persist to know the real story. Even those outside the LGBTQ community search for uncensored translations or watch with subtitles. A new generation of Eastern European queers is finding itself through this series.

It made me reflect on the role of mass culture — especially American mass culture — globally. I use Ukraine and Russia as examples because I’m from Ukraine, spent much of my childhood and adolescence in Russia, and speak both languages. But the impact is clearly broader. The evolution of mass culture changes the world, and in the context of queer history, “Interview with the Vampire” is one of the brightest examples — precisely because of its international reach and because it was never marketed as “gay literature,” but as gothic horror for a general audience.

With AMC now producing a third season, “The Vampire Lestat,” I’ve seen renewed speculation about Lestat’s queerness and debates about how explicitly the show portrays same-sex relationships. In the books, vampires cannot have sex in a “traditional” way, but that never stopped Anne Rice from depicting deeply homoromantic relationships, charged with unmistakable homoerotic tension. This is, after all, a story about two men who “adopt” a child and form a de facto queer family. And this is just the first book — in later novels we see a lot of openly queer couples and relationships.

The first novel, “Interview with the Vampire” was published in 1976, so the absence of explicit gay sex scenes is unsurprising. Later, Anne Rice — who identified as queer — described herself as lacking a sense of gender, seeing herself as a gay man and viewing the world in a “bisexual way.” She openly confirmed that all her vampires are bisexual: a benefit of the Dark Gift, where gender becomes irrelevant.

This is why her work resonates so powerfully with queer readers worldwide, and why so many recognize themselves in her vampires. For many young people I know from Eastern Europe, “Interview with the Vampire” was the first book in which they ever encountered a same-sex relationship.

But the true power of this universe lies in the fact that it was not created only for queer audiences. I know conservative Muslims with deeply traditional views who loved “The Vampire Chronicles” as teenagers. I know straight Western couples who did too. Even people who initially found same-sex relationships unsettling often became more tolerant after reading the books, watching the movie or the show. It is harder to hate someone who reminds you of a beloved character.

That is the strength of the story: it was never framed as explicitly queer or purely romantic, gothic and geeky audiences love it. “The Vampire Chronicles” are not a cure for queerphobia, but they are a powerful tool for making queerness more accessible. Popular culture offers a window into queer lives — and the broader that window, the more powerful it becomes.

Other examples include Will from “Stranger Things,” Ellie and Dina from “The Last of Us” (both the game and the series), or even the less mainstream but influential sci-fi show “Severance.” These stories allow audiences around the world to see queer people beyond stereotypes. That is the power of representation — not just for queer people themselves, but for society as a whole. It makes queer people look like real people, even when they are controversial blood-drinkers with fangs, or two girls surviving a fungal apocalypse.

Mass culture is a universal language, spoken worldwide. And that is precisely why censorship so often tries — and fails — to silence it.

-

Virginia3 days ago

Virginia3 days agoMcPike wins special election for Va. House of Delegates

-

New York5 days ago

New York5 days agoPride flag removed from Stonewall Monument as Trump targets LGBTQ landmarks

-

Florida5 days ago

Florida5 days agoDisney’s Gay Days ‘has not been canceled’ despite political challenges

-

Philippines5 days ago

Philippines5 days agoPhilippines Supreme Court rules same-sex couples can co-own property