Obituary

Trailblazing Maine lawmaker Lois Galgay Reckitt dies at 78

State representative co-founded HRC Fund, fought for domestic violence survivors

After spending many happy summers at Goose Rocks Beach in Maine, Lois Galgay told her mother when she was 7 that she wanted to move to Maine. Her mother suggested she wait until she grew up.

She waited, but she did end up in Maine in her 20s and became the fiercest advocate for woman and children the state has ever seen, her decades-long advocacy ending only with her death from cancer Oct. 30, 2023, at the age of 78. Maine recognized her achievements by inducting her into the Maine Women’s Hall of Fame and the Deborah Morton Society, and by giving her awards for her seminal work on domestic violence. The judicial system, the state bar association and the police chiefs’ association all honored her.

But she also was a leader on the national stage. The headline in Ms. Magazine after her death read: “Rest in Power: Lois Galgay Reckitt, Trailblazing Feminist Activist.”

Eleanor Smeal, an activist since the 1970s who was once called one of the most influential women in America, wrote these words in the magazine: “Lois Reckitt has not only been an inspirational leader for women and girls in Maine, but also nationwide. Lois was a champion for the Equal Rights Amendment both for the United States Constitution and the Maine Constitution. She was a leader in the National Organization for Women and a national leader in the fight to end violence against women and girls. I had the good fortune to work with her closely when I was president of the National Organization for Women, and she was the executive vice president. She worked for women’s rights until the time of her death and was very proud that she had just passed historic legislation in Maine to end sex trafficking.”

Reckitt was on NOW’s national board for 15 years and from 1984 to 1988 was executive vice president. She was elected to the position, and pursued the work with a vengeance, working 60 to 70 hours a week. She also served for eight years on the national board of the Human Rights Campaign Fund, a political action group she cofounded and replicated in Maine. She was a member of the National Coalition to End Domestic Violence for many years.

She is listed in “Feminists Who changed America ’63-’75.”

Reckitt grew up in Massachusetts, an only child and the daughter of parents who both were polio survivors. She came to Maine by following her husband, who was stationed in the Coast Guard in South Portland. She said she had no clue she was a lesbian at that time. That truth came to her during two marriages, and in due time she came out and became a champion for gay rights.

She was preceded in death by her father, George A. Galway of Winthrop, Mass., and her mother, Marjorie Lewis Wright of South Portland.

She is survived by Lyn Kjenstad Carter, her loving partner/wife of 20 years; stepdaughter, Barbara M. Carter-Eide, son-in-law, Pala Carter-Eide, stepdaughter, Crystal L. Hartford; five grandchildren; and many cousins in the Galway and Wright families.

She was not only a national leader on domestic violence — she was a true leader in Maine. She founded Family Crisis Shelter, which became Family Crisis Services, now Through These Doors, and headed it for more than three decades, taking time out for her work in Washington, D.C. When she returned to Maine, she was exhausted and said she would do nothing but sleep for six months. But she resumed her work, heading an agency with a $1.4 million budget, a staff of 30, three outreach offices and a battered women’s shelter. At the forefront of efforts to stop domestic abuse and help its victims, she lobbied for stronger laws and more aggressive enforcement of them. She raised public awareness of the magnitude of domestic abuse while lobbying successfully for anti-stalking legislation, a domestic violence homicide review panel and gun control measures for abusers.

She worked not just to pass laws but to help police, prosecutors and judges better understand domestic violence and the harm it caused. “Her approach rested on her belief that people want to do what is right and just, and that most people will respond better to a victim’s needs if that person has knowledge of the dynamics of domestic violence,” said retired Judge Michael Cantara, a longtime friend.

Reckitt led many groups, but sometimes had to create them first. Maine’s NOW chapter, the Maine Right to Choose, the Maine Coalition for Human Rights and the Matlovich Society for Gay Rights and AIDS Awareness were among the organizations that were created, in whole or in part, by her. Forty-five years ago, she and eight others, including now-Gov. Janet Mills, founded the Maine Women’s Lobby. Destia Hohman Sprague, current Women’s Lobby executive director, said Reckitt “set such a profound example of what it is like to work on an issue, to follow your heart and to work on an issue in every possible way. She never gave up working as an activist and then a policy maker, and I just admire that so much.”

State leaders lauded her on her passing, calling her a trailblazer, a feminist icon, a hero, a modern pioneer and “a truly remarkable person.”

“Lois never stopped trying to make our state better for everyone,” said Mills, who went to her home to swear her in for her last legislative term. “She was a dear friend, and I will miss her deeply.”

Reckitt knew her work would take endurance, a requirement that may have tested her mettle, but she never gave up. She introduced an Equal Rights Amendment in the Maine Legislature three times and was rebuffed every time. She helped create the coalition that put forward the first gay rights bill in Maine. She and other activists thought it would take 10 years to pass a law. It took 25. She could find only two sponsors. One was Gerald Talbot, the first black man elected to the Maine Legislature. To learn more about gay rights, Talbot went a bookstore to get a book. “They wouldn’t take the money out of his hand because they thought he was gay,” Reckitt recalled. The incident showed the difficulty they were up against. Reckitt provided the lead testimony on the bill, but even though no one spoke against it, it failed.

She came out at this time, but minimally. She decided to stay closeted until the first campaign was over and came out afterwards at the farmhouse of a straight friend in Newcastle. Gay rights were in her playbook from that moment on. Working with a gay man who was dying of AIDS, she founded a group that provided a safe space for gays and lesbians to gather, a way of lessening their isolation. It began with six or seven people and soon mushroomed to be as many as 150, some driving hours to get there. She would be a pallbearer at the man’s funeral.

Despite the intensity of her work to fix things that were broken, she wasn’t a rabble rouser — she tended to work behind the scenes — but she was arrested twice, once while protesting apartheid at the South African embassy in Washington. She jumped into the national fray again when the national gay rights movement went to Washington to protest Reagan’s inadequate response to the AIDS crisis. In an oral history interview, she was clearly dismayed that Reagan had never spoken the word AIDS. “Reagan was such a ditz,” she said.

Outside the White House, she protested in the prosaic way it was done in those days: sitting down and refusing to move. Sixty-seven people were arrested. She was the first, “not because I was particularly outrageous or anything” but because of the way the protest was set up, she said in her oral history interview. She claimed to have “the odd distinction of being the first women in the U.S. arrested by police using those Playtex rubber gloves,” which they used to “reach down my pants to see if I was carrying who knows what.”

She had widespread interests, including her Irish ancestry. She knitted, quilted and did needlepoint, traveled extensively, taught swimming and biology, played basketball in college. Most importantly, she loved the Boston Red Sox and Celtics.

In seeming contradiction to her life’s work, she received college degrees from Brandeis University in biology and from Boston University in marine biology and biological oceanography. But she said her scientific education taught her how to approach things in life.

“She loved the sea, and she loved that she lived only steps from the beach,” said longtime friend Lee Umphrey. “She liked to say her legislative district was on the ocean side of South Portland.”

She once said the three loves of her life were the women’s rights movement, the lesbian rights movement and the movement to end violence women. “I have lived an interesting life,” she said.

“Lois came of age when the civil rights movement, the environmental protection movement, the anti-Vietnam movement, the anti-apartheid movement, and the equality for women movement were front and center,” said Cantara, the retired judge. “She chose to become a lifelong engaged citizen who advocated for the poor, the marginalized, the forgotten, the dismissed. She took her legislative duties very seriously. She was working on legislative matters up to two days before she died.”

She even participated in a national conference from her hospital bed, one that focused on her pioneering Maine work to end sexual exploitation. In appreciation, the National Center on Sexual Exploitation gave her the Dignity Defense Award. “To the very end, Lois was in the saddle championing equality,” Umphrey said. “She gave it her all until the end.”

But in her 1999 oral history interview, she wondered what her life would add up to. “One of the things I’ve been concerned about my life is to not have my life disappear,” she said. “I figure somebody will remember sometime that I set foot on the planet. I’ve done a lot of good stuff. I know that, and I figure I’m only half done.”

A celebration of her life took place on Nov. 12, at the Maine Irish Heritage Center in Portland. Reckitt had been on the center’s board and its treasurer.

In lieu of flowers, donations are suggested to:

Through These Doors at

737-234-6464; OR

The Maine Irish Heritage Center,

34 Gray St.,

Portland, Maine, 04112-7588

207-780-0118

District of Columbia

Acclaimed bisexual activist, author Loraine Hutchins dies at 77

Lifelong D.C.-area resident was LGBTQ rights advocate, sex educator

Loraine Adele Hutchins, a nationally known and acclaimed advocate for bisexual and LGBTQ rights, co-author and editor of a groundbreaking book on bisexuality, and who taught courses in sexuality, and women’s and LGBTQ studies at a community college in Maryland, died Nov. 19 from complications related to cancer. She was 77.

Hutchins, who told the Washington Blade in a 2023 interview that she self-identified as a bisexual woman, is credited with playing a lead role in advocating for the rights of bisexual people on a local, state, and national level as well as with LGBTQ organizations, many of which bi activists have said were ignoring the needs of the bi community up until recent years.

“Throughout her life, Loraine dedicated herself to working and speaking for those who might not be otherwise heard,” her sister, Rebecca Hutchins, said in a family write-up on Loraine Hutchins’s life and career.

Born in Washington, D.C., and raised in Takoma Park, Md., Rebecca Hutchins said her sister embraced their parents’ involvement in the U.S. civil rights movement.

“She was a child of the ‘60s and proudly recalls attending Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech with her mother on the D.C. Mall,” she says in her write-up. “She was steeped in the civil rights movement, was a member of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, and was proud to say she had an FBI record.”

The write-up says Hutchins received a bachelor’s degree from Shimer College in Mount Carroll, Ill. in 1970, and a Ph.D. in 2001 from Union Institute. It says she was also a graduate of the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Sexuality’s Sexological Bodyworkers certification training program.

The family write-up says in the 1970s Hutchins became involved with efforts to assist tenants, including immigrant tenants, in affordable housing programs in D.C.’s Adams Morgan neighborhood.

“In 1991, she co-authored the groundbreaking book, ‘Bi Any Other Name: Bisexual People SPEAK OUT’ with friend and colleague Lani Ka’ahumanu,” the write-up says. It notes that the acclaimed book has been republished three times and in 2007 it was published in Taiwan in Mandarin.

According to the write-up, Hutchins delivered the keynote address in June 2006 at the Ninth International Conference on Bisexuality, Gender and Sexual Diversity. In October 2009, D.C.’s Rainbow History Project honored her as one of its Community Pioneers for her activist work.

“Loraine is one of the few people who has explained, defended and championed bisexuality and made sure the “B” got into the LGBT acronym,” the Rainbow History Project says on its website in a 2009 statement. “Sensitivity to bisexual issues, civil rights, and social justice issues is Loraine’s life work,” the statement concludes.

The write-up by her sister says that up until the time of her retirement, Hutchins taught women’s and LGBT studies as well as health issues in sexuality at Montgomery Community College and Towson University in Maryland.

“She was a friend and mentor to many in the LGBTQ community,” it says. “She thoroughly enjoyed adversarial banter on the many topics she held dear: sexuality, freedom of speech, civil rights, needs and support of those with disabilities, especially in the area of mobility, assisted housing, liberal politics and many other causes,” it points out.

She retired to the Friends House community in Sandy Springs, Md., where she continued her activism, the write-up concludes.

Hutchins was among several prominent bisexual activists interviewed by the Washington Blade at the time of her retirement in June 2023 for a story on the status of the bisexual rights movement. She noted that, among other things, in her role as co-founder the organizations BiNet USA and the Alliance of Multicultural Bisexuals, she joined her bi colleagues in prodding national LGBTQ advocacy organizations to improve their advocacy work for bisexuals, which Hutchins said had been inadequate in the past but had been improving in recent years.

Hutchins is survived by her sister, Rebecca Hutchins; her husband, Dave Lohman; nephew, Corey Lohman and his wife Teah Duvall Lohman; and cousins, the family write-up says.

It says a private memorial service was scheduled for December and a public memorial service recognizing her contributions to the LGBTQ community will be held in the spring of 2026.

Obituary

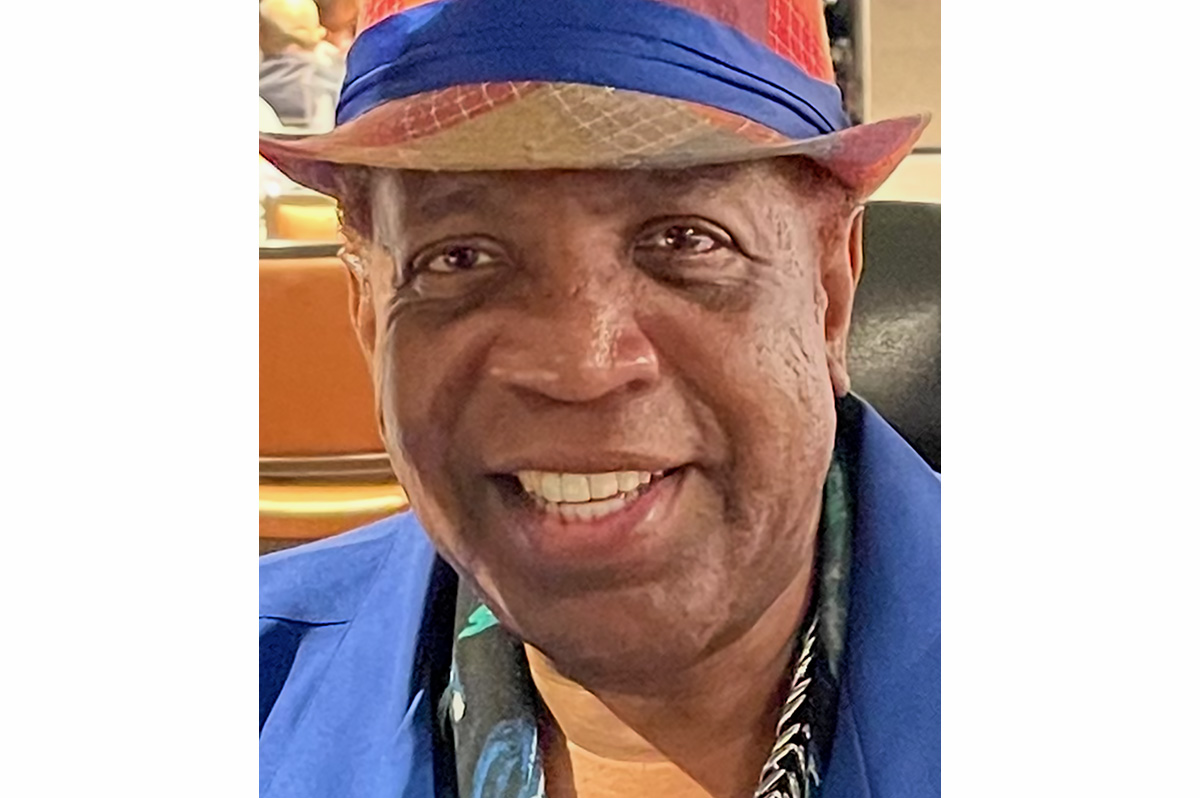

Acclaimed disability rights advocate Thomas Mangrum dies at 61

Lifelong D.C. resident also served as ‘cherished’ Capital Pride volunteer

L. Thomas Magnum Jr., a lifelong D.C. resident, widely recognized and acclaimed advocate for people with disabilities, and LGBTQ rights activist involved in the city’s Capital Pride events, died Sept. 17 from complications related to stomach cancer. He was 61.

A statement released by Project ACTION!, a local disability advocacy organization for which Mangrum served for 15 years as co-president, says he worked for more than 20 years for the D.C.-based Maurice Electric Supply company before retiring in 2002 and devoting his efforts to disability-related projects and programs.

Phylis Holton, an official with the D.C. organization Quality Trust For Individuals With Disabilities and a longtime friend of Mangrum, said as a person with a developmental disability Mangrum devoted his life to supporting others with all forms of disabilities. She said that due to a separate spinal condition, Mangrum used a wheelchair for about 15 years prior to his passing.

Holton said Mangrum had a mild form of developmental disability, which the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes as “a group of conditions due to an impairment in physical, learning, language or behavior areas” that usually develops before a child is born during pregnancy.

Holton said Mangrum was an active member of Project ACTION! for 15 years prior to the 15 years he served as the organization’s co-president.

“He traveled nationally and presented at conferences, was featured on webinars and podcasts on a variety of topics related to self-advocacy, accessibility, equality, and more,” Holton told the Washington Blade in a statement.

“He shared his lived experience of being a Black man with a disability, and being gay, and how it impacted how he was treated in the community,” Holton said. “He was a strong advocate and co-facilitated trainings for independent advocacy organizations that Thomas supported and was a key advocate in their advocacy work,” she said.

Holton added, “He would answer a late request to train a group of attorneys, present at a meeting or testify before City Council or meet with an advocacy group to advance pending legislation that impacted people with disabilities.”

She said Mangrum also enjoyed participating in LGBTQ Pride events and last year traveled to the New York Pride events. According to Holton, he looked forward to participating in WorldPride 2025 events earlier this year in D.C. “but his illness prevented him from doing so.”

In a statement announcing Mangrum’s passing, Capital Pride Alliance, the group that organizes D.C.’s annual LGBTQ Pride events and served as the lead organizer of WorldPride 2025 in D.C., called Mangrum a “cherished volunteer” for D.C. Pride events.

June Crenshaw, the Capital Pride Alliance Deputy Director, said Mangrum served as a volunteer for D.C.’s LGBTQ Pride events “for many years” and was involved in many of the planning activities for WorldPride before his illness prevented him from participating in WorldPride earlier this year.

“He certainly in my interaction with him made me very aware of making sure that Capital Pride was thinking about accessibility always, and making sure that we had a welcoming, affirming accessible space for participants and staff with disabilities,” Crenshaw said.

In its statement on Mangrum’s career and accomplishments in life, Project ACTION! says he helped to advance the needs of people with disabilities through service on many boards and commissions. Among them were Lifeline Partnership, the D.C. Developmental Disabilities Council, the D.C. Center for Independent Living, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transportation Authority’s Accountability Advisory Committee, “and many more.”

“His leadership, passion, and unwavering commitment to equity and inclusion made a lasting impact on all who had the privilege to know and work alongside him,” the statement says.

It adds, “Thomas showed us the power of perseverance, courage, and the importance of standing together. His spirit will continue to guide us and strengthen our community for generations to come.”

A funeral for Mangrum was scheduled for Oct. 9, at D.C.’s Westminster Presbyterian Church at 400 I Street, S.W., with a viewing at 10 a.m. followed by a program at 11 a.m. A burial was scheduled to take place that same day at Heritage Memorial Cemetery at 13472 Poplar Hill Road in Waldorf, Md.

Holton said in lieu of flowers, donations may be made to Project ACTION! for a Celebration of Life and advocacy scholarship in Mangrum’s name. A date and location for the Celebration of Life for Mangrum was to be announced later, according to Project ACTION!

Obituary

Susan Xenarios, crime victim advocate, long-time LGBTQ ally, dies at 79

‘Susan was a force of nature, a mentor’

Susan Xenarios, LCSW, a visionary and dynamic leader of New York’s crime victim movement for 50 years and a courageous ally of the LGBTQ community, died on Sept. 6 in Manhattan. She was 79.

In 1974, an assailant held a knife to Ms. Xenarios’s throat and raped her on a rooftop in Upper Manhattan. At a time when few sexual assault victims spoke out, she began a lifelong, public campaign to improve the care and treatment of survivors and to reform laws and police procedures. Along with her high-profile advocacy, she never stopped counseling individual survivors of crime, pioneering breakthrough therapeutic interventions.

Ms. Xenarios led the creation of New York’s first program to provide assistance to survivors of sexual assault, the state’s first clinical program for male survivors, and the New York Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner (SAFE) Program, which ensures survivor-centered emergency room protocols, including evidence collection. She served as executive director of the Crime Victims Treatment Center in New York City for 40 years (1977 -2017).

Ms. Xenarios also was a driving force behind several state laws to advance the rights of crime survivors, including a 1993 law protecting the confidentiality of rape crisis center communications, the Hate Crimes Act 2000, which included enhanced penalties for hate-motivated crimes, including anti-LGBTQ assaults, and the 2015 “Enough is Enough” law, one of the first laws in the nation to require all colleges to adopt a set of comprehensive procedures for addressing sexual violence on campuses.

“Susan was a force of nature, a mentor, an extraordinary ally to the LGBT community, and a dear friend,” said Bea Hanson, director of the New York State Office of Victim Services, principal deputy director of the federal Office on Violence Against Women during President Barack Obama’s administration (2011-2017), and director of client services of the New York City Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project (1991-1997). “She was a leader in advocating for the rights of sexual assault survivors and all crime victims. She spoke truth to power with a smile on her face and love in her heart. She will be missed.”

“Susan was the greatest champion and friend of LGBT victims of crime there ever was or ever will be,” said Matt Foreman, former executive director of the NYC Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project (1990-1996) and the Empire State Pride Agenda (1996-2003). “She was one of the first to recognize the prevalence of sexual assault against men and she created the first program to help male survivors. When there was enormous pressure to pass a hate crimes law that did not include anti-LGBT offenses, she made sure the larger movement did not abandon us. She understood the harmful effects of having terms like ‘sodomy’ and ‘deviate sexual intercourse’ in New York State law and led the successful drive to purge them from the books. She was so genuinely warm and supportive, I was shocked when I learned that she wasn’t a lesbian.”

A memorial service will be held on Saturday, Sept. 20, at 11 a.m. at West End Collegiate Church, 245 W. 77th St. in Manhattan.

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoTrump falsely links trans people to terrorism

-

Virginia5 days ago

Virginia5 days agoFellow lawmakers praise Adam Ebbin after Va. Senate farewell address

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoLGBTQ activists mourn the Rev. Jesse Jackson

-

Massachusetts4 days ago

Massachusetts4 days agoEXCLUSIVE: Markey says transgender rights fight is ‘next frontier’