Opinions

Activism, the black athlete and supporting LGBT equality

Ali’s legacy and why Kaepernick’s critics are wrong

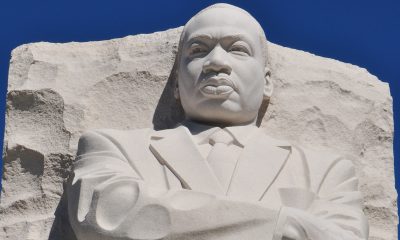

Why do we praise Muhammad Ali, yet criticize Colin Kaepernick? (Photo by Mike Morbeck; courtesy Flickr)

Why do so many African-American professional athletes today view Muhammad Ali as a hero, but fall short of even trying to live by the same code of ethics that made him a hero? Ali became a hero because he was never silent. He said things he knew would make people uncomfortable, even angry, but that he believed would help bring about awareness and change. Ali was, as a result, a controversial figure during his life. He angered countless people with his message and many people hated him. It was only later that Ali was recognized for his impact on our country.

I remember that once as a boy I heard Ali call himself “pretty” on TV. This was before Beyoncé made big booties sexy, before girls were pumping their lips full of fillers. This was the 1970s. “Black” features were not considered pretty. I remember how powerful it was to see a man who looked like me categorize himself that way. I was nine years old, and I have never forgotten that moment. It was a small moment, but one that empowered me to feel good about myself. That is the power we possess as professional athletes: We have a platform to speak, and a way to give voice to so many voices that remain unheard. We have the ability, and I believe, the responsibility, to serve as a voice that will empower and engage others. But that platform, and the power it gives us, is an opportunity too many of us ignore.

When I started writing this piece, my intention was to draw attention to Black athletes who admire Ali for his activism, but remain silent as injustices continue to reveal the persistent inequity in this country. More specifically, I wanted to center that discussion on the fact that African-American heterosexual males have remained noticeably absent in the fight for equal rights for the LGBTQ community, being that we are all too familiar with what it feels like to be a disenfranchised and discriminated against minority. Before I finished the piece, however, I saw San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick sit down for the national anthem — and I saw America stand up in protest. When asked why he didn’t stand, Kaepernick said he was “not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses Black people and people of color.”

The way Kaepernick took a stand was exactly the type of activism I wanted to see among today’s Black athletes, but before I had time to applaud him, the media crucified him. Worse yet, it wasn’t just the mainstream media that was speaking out. Even fellow Black athletes were speaking out against him. It was bad enough that so many Black athletes were willing to be silent and let others stand up for our people, but now some were actually chastising him for standing up for us. Kaepernick wanted dialogue, but instead he got told that he had crossed a line. He wanted to spark conversation, but instead he was told to be quiet. In fact, he was told to be grateful.

Ironically, one of the criticisms of Kaepernick came in the form of an argument that Kaepernick was not in a position to stand up for Black people because he was not Black. Forgetting about the fact that Kaepernick is in fact half Black, that position itself is nonsensical. If he were white, would it be wrong for him to stand up for Black people? Does that mean that white people cannot defend the rights of Blacks or other minority groups? That straight people cannot defend the rights of the LGBTQ community? Historically, no minority group has ever gained the equal rights they sought without the support of the majority.

And it’s true that Kaepernick does not necessarily feel the impact of racism or injustice day to day ⎯ he is not part of the disenfranchised Black community he is fighting to protect. The Civil Rights leaders of the 1950s, such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, were standing up for their own rights along with the rights of the Black community ⎯ King couldn’t sit at the front of the bus either. Kaepernick is educated, and has a multi-million dollar contract as a quarterback in the NFL. But in my mind that makes his action even more powerful, not less. His silent protest was not driven by self-interest. He chose to speak for those who don’t have a voice. As he put it, “This country stands for freedom, liberty, justice for all ⎯ and it’s not happening for all right now.” That was reason enough for him to take action, despite any repercussion he might face. That is what makes him a leader.

So why are so few athletes willing to stand up — or, in Kaepernick’s case, sit down? Many people do not realize that if a player has made it to the NFL, he has been playing since he was a child. From that time, he has been systematically trained to aspire to be in the NFL. Once a player makes it to the league, his impulse is, one, to fall in line, to do nothing that might jeopardize his team, a sacred brotherhood. Two, not to do anything to jeopardize his salary or endorsements. More than half of the players in the NFL come from poverty. For more than half the players in the league, football is the only way they see to take care of themselves and their families.

But the impulse and pressure to fall in line is what keeps so many players from standing up the way Kaepernick has — and keeps so many players silent when they could be voices of change. The unfortunate truth is that their fears are not unfounded. Broncos linebacker Brandon Marshall, who has chosen to take a knee for the anthem in light of Kaepernick’s protest, has already lost two endorsements as a result of his actions. While too many of us still sit on the sidelines in the fight for justice, I am heartened that Kaepernick’s activism has begun to gain momentum: more athletes take a knee, raise their firsts, link arms in support of him and his message. Even 49ers owner Jed York came out in full support of Kaepernick. Despite sacrificing two endorsements, Marshall remains steadfast in his commitment to the protest, and the conversation he hopes it will inspire.

I would love to see this momentum continue to build and have more professional Black athletes stand up publically for the larger Black community. But what I would also love to see is that activism stretch beyond the reach of our own people and begin to try to help yet another marginalized group, the LGBTQ community.

There is an unmistakable power balance in this country, and we all know who wields that power. That being said, within the other groups that comprise our nation, there does exist a hierarchy of power. That hierarchy is what gave Kaepernick the opportunity to stand up for his beliefs in a way that a lot of other Black men never could. It is also what allowed the entire football team and the entire student body at University of Missouri to stand up for Michael Sam, and allow him to live his life openly as a gay man (which, by the way allowed him to play the best season of his entire collegiate career). And, two years later allowed the Missouri football team to stand together as a team against the racial discrimination that was occurring on their campus and boycott playing a single game until they got a public apology from the president of the university. Regardless of our race, as athletes, we do in fact wield power. The power to raise our voices for change is in our hands, but I see so much silence.

The LGBTQ community is another minority community in our country that is still fighting to be truly equal under the laws of our nation. And while I am by no means saying that the Black fight for equality is over, what I am saying is that there are many Black people in this country, such as professional athletes, that do in fact have a tremendous platform with which they can show support for the LBGTQ community. We have power to not only help ourselves, but to help another group who seeks fairness and equity.

If more professional athletes stood up for the LGBTQ community the same way Muhammad Ali and Colin Kaepernick did and the way others are beginning to do, think of the impact and the power that would have on the LGBTQ community and their fight for equality. Think about what would happen if two of my favorite athletes ⎯ Michael Jordan and LeBron James — went to Nike and said they wanted to film a PSA because they had a family member or close friend who is gay and wanted to publicly show their support. Because let’s face it, we all have at least one family member or close friend that is a part of the LGBTQ community. But instead we allow ourselves to be told by the corporations what we can and cannot do. Why can’t we realize that we have just as much if not more power than the students at University of Missouri? If we stand together on the right side of history, then the power is ours. We need to be on the front line of history, not wait until it is cool to be in support of something that is not allowing friends and family members to feel safe and live their life to fullest.

In our community there is still a widespread fear that being an advocate for, or even just an ally of the LGBTQ community will call into question our own sexuality or masculinity as straight Black men. The base level of this fear is straight forward (albeit based on a false assumption) that supporting the LGBTQ community will lead people to think that we are gay or less of a man. As a result, many of us would rather say nothing than do something that would lead others to have that perception of us. There is also a financial fear associated with being a straight ally. That fear being that if people think that we are homosexual or an ally to the LGBTQ community, it will have a detrimental effect our brand, and in turn, our wallet.

I also want to address the argument that religious people cannot support the LGBTQ community due to the teachings of the Bible. First of all, I would like to remind all of my Black brothers and sisters that it was not too long ago that people used verses from the Bible to back up arguments to keep slavery legal. We, as African Americans cannot in good faith use the same teachings that were used to oppress us to suppress the rights of another group of people. Second, I would love someone to tell me when the laws in the Bible got ranked. In other words, what divine power came down and told us that the teachings that prohibit homosexuality are more important than the teachings that tell us to “love your neighbor as yourself?”

We must begin to the dispel the ideas held by so many straight Black men that being an ally to the LGBTQ community will hurt them in some way. In order to do this, there are two major revelations to which these athletes must come. The first is that the stereotypes they grew up hearing are antiquated and untrue. We must all be a part of eliminating these stereotypes, and we can do that simply by letting our words and our actions defy them. The second is that becoming a straight ally for the LGBTQ community will actually broaden their brand and appeal. The LGBTQ community accounts for more than $9 billion of buying power in this country. When Michael Sam came out as a gay man, his jersey shot straight to the No. 2 most purchased NFL jersey in the country. When Steve Jobs died, Tim Cook took over as CEO of Apple, and has subsequently come out as a gay man. We all still walk around with our iPhones tight in our clutches, but how many of us stop to think about the fact that the company that makes them — one of the most powerful companies in the country — is run by an openly gay man?

Muhammad Ali has, in the wake of his death, been mourned and celebrated in the media as an athlete who transcended sport and became an icon of activism and social justice. However, the same people who praise Ali for his activism and commitment to social justice can, almost in the same breath, condemn Colin Kaepernick for attempting to use his platform as an athlete to do the same. Ali paved the way for athletes like Kaepernick to speak out. If we celebrate Ali for creating the path, then how can we disapprove of athletes like Kaepernick for walking it?

It is time Black athletes realize our power and responsibility to bring change in America — and it is time for America to stop fearing what the change will look like. We must say and do the things that will spark conversation about important issues that we face because conversation is the first step toward resolution.

If we cannot speak about the issues, how can we hope to resolve them? More specifically, we, as heterosexual Black men with a voice need to get on the right side of history in the fight for LGBTQ equality. It is our responsibility to stand up for the underdog, the discriminated against, because we have been and still are discriminated against. We must stand up for communities other than our own just as we want others to stand up for us. We must be upstanders and not bystanders, we must stand up and use our voice for change, acknowledging that no group of human beings deserves to be treated as inferior.

We must applaud Kaeperrnick for his actions by acknowledging that great leaders have the strength and conviction to never mistake the easy choice for the right one. But applauding him is not enough. We must accept that once we identify a great leader such as him, we must have enough of our own strength and conviction to follow him.

Sean James is executive director of Sports & Entertainment for Hotaling Group Insurance Services and a former NFL player.

Republican representatives in the Kansas Legislature recently passed a bill that bans people from using restrooms in government buildings that do not align with their sex assigned at birth. The bills SB 224 and HB2426 initially focused on rewriting legislation surrounding driver’s licenses but after amendments, the bill would not only stop trans people from updating their gender on these driver’s licenses but force people to surrender their existing licenses. These bills also carry the most severe anti-trans bathrooms ban of any state.

According to Erin Reed for Erin In The Morning (EITM), “the measures would now even empower private citizens to act as bounty hunters — entering private business to search for transgender people in bathrooms and sue them for alleged violations.”

The bills would allow anyone to report any people who utilize any bathrooms that do not align with their gender assigned at birth. Anyone who believes that someone has entered a restroom not in alignment with their gender assigned at birth can complain and pursue $1,000 in damages. The first time that someone complains about a person using the “wrong” bathroom, that person can face a written warning for their first violation. The second violation would require them to pay a $1,000 fine, and with each additional violation, they could receive a misdemeanor resulting in another fine or up to six months in jail.

The Kansas Attorney General’s office is then responsible for determining whether the person has to pay the fine. Allowing people to police bathroom spaces is reminiscent of Florida’s bathroom law that allows transgender people to face criminal penalties, but even more dangerous, the bills extend this enforcement from “government-owned buildings” to private spaces.

Government entities that manage bathrooms and locker rooms at public schools and universities, highway rest areas, and public parks are now required to assign a gender designation to multi-occupancy private facilities or face a $25,000 fine for the first violation and a $125,000 fine for any additional violations.

There is a section, Reed notes, that creates a “private right of action,” making it the first law to penalize trans people directly for using the restroom and would extend bathroom bans into private spaces. “Without the option of single-person or family alternatives, this essentially forces trans people out of public life by denying us the right to even relieve ourselves or wash up,” Isaac Johnson of Trans Lawrence Coalition told EITM.

“Denying access to basic public amenities doesn’t just inconvenience people; it relegates them to second class citizenship,” Allison Chapman of Lawyers for Good Government told EITM.

The legislation flew through the Kansas Congress (and by using procedural maneuvers, Republican lawmakers ensured that there was no public input on the bill). The bill is now heading to the Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly’s desk for signature. Thankfully, Kelly, a Democrat who has consistently vetoed anti-trans legislation, vetoed it, but even so, it could be passed if Kansas Republicans get the support of two-thirds of lawmakers in both chambers.

The quick passage of these bills, and using the “gut-and-go” measure to ensure people had no opportunity to provide feedback after the bathroom elements were added, has drawn swift criticism.

The bills themselves have deeply unsettling historical parallels to slave catcher laws that allowed “bounty hunters” to track down and return escaped enslaved individuals to their enslavers for a cash reward. Federal laws, like the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850, enabled “bounty hunters” to operate even in free Northern states. These “bounty hunters,” also known as “slave catchers” or “kidnapping clubs” frequently kidnapped free Black people and sold them back into slavery, in what has been called the “Reverse Underground Railroad.”

Both of these acts provided little to no protection to free Black Americans; in fact, these acts aided and abetted this violence by incentivizing the kidnapping and sale of people of color into slavery. Even if free people had official “freedom papers,” many kidnappers destroyed these documents, and even free people of color typically could not testify in court. Free and previously enslaved Black children who had escaped to the North were especially vulnerable to “slave catchers” because they often did not know how to assert their rights.

In fact, ICE’s kidnapping of five-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos echoes this long history of child snatching in the U.S., from bounty hunters capturing and selling Black children into slavery.

This legislation also reeks of Texas Senate Bill 8 (SB 8), enacted in September 2021, that allowed private citizens to sue anyone who aids or performs an abortion after the detection of a fetal heartbeat, around six weeks of pregnancy. At the time, this was the most severe anti-abortion legislation on the books. It has remained there for five years, leading to a number of Rule 202 petitions that aim to collect more information that would provide a person who has violated SB 8.

Just this past month, the Texas Supreme Court heard oral arguments for Sadie Weldon v. The Lilith Fund, a case where a private Texas citizen sought to depose Neesha Davé, deputy director of the Lilith Fund, a nonprofit that supports people seeking abortions. The case will not rule on SB 8’s constitutionality but would open a path to challenge the law.

Bathrooms have long been a battleground to police people’s bodies, and this new Kansas soon-to-be law is no different. Think of segregation in the Jim Crow South between the 1890s and the mid-1960s when some White people acted as vigilantes ensuring that Black people remained out of “white-only” restrooms and other “white-only” spaces.

Just as Rep. Susan Hemphries, a Wichita-based Republican who brought the bill to the House floor said that the legislation is about the privacy for and safety of women, bathroom segregation was often justified by painting Black male sexuality as a threat to white women.

This even extended to the perceived threat of Black women in white women’s restrooms, with one group of white women in Detroit going on strike to protest the order prohibiting discrimination of people working in government and defense industries. These white women argued that they would contract syphilis from sharing toilet seats with Black women.

These new bills and all other anti-trans bathroom legislation, as many have argued, are the continuation of these racist bathroom restrictions.

There is deep historical precedence not only for policing public (and private) bathroom access but also enabling private citizens to act as bounty hunters. This form of bounty hunting threatens not just trans women but all women who anyone does not “assume” is cisgender who may be subject to legal complaints. As Orien Rummler reported for the 19th and them, anti-trans legislation and rulings threaten the rights of all women, especially cis women of color. And as science has long proved, gender is not binary–so it raises the question of how intersex people will be policed in these restrooms.

And by commodifying the bounty, it emboldens anti-trans violence, and misogynistic violence writ large, in the most intimate of public and private spaces.

Emma Cieslik is a museum worker and public historian.

Opinions

Criteria for supporting a candidate in D.C.

We deserve statehood and mayoral control of our National Guard

Choosing a candidate to support for office in D.C. is a little different than choosing one in other places. As everyone knows, D.C. isn’t a state; though apparently not everyone understands what that means.

D.C. was granted home rule in 1974, but the legislation gave us only partial control of our government. Congress retained the right to review all legislation and budgets for 30 days. During that time, it can reject legislation fully or just make changes. Recently, Congress has used that power to turn down legislation when the Council revised our criminal code and screwed with legislation regarding how we tax our own residents. Congress has messed with our budgets as well. We saw what happened when the felon in the White House took control of the MPD for 30 days, allowed under the home rule legislation, and how he has full control over the D.C. National Guard and the implications that has had.

We have no representation in Congress, just a delegate. That person has been given a vote in committees when Democrats controlled the House, but even then, no vote in the full House. That all has severe implications for our elected officials. They must be aware of these things when they speak out, and when they propose and pass legislation. I personally saw that close up when we fought for marriage equality in the District. Those of us leading the charge worked with the Council on legislation to first recognize gay marriages from other states. Only after that legislation went through the review period without being stopped did the Council move to pass marriage equality in the District. Then we held our breath for the 30-day review period. There have been other instances where Congress stopped crucial legislation and put amendments onto our bills, like stopping us from spending certain money on needle exchange during the height of the AIDS crisis and stopping us from spending federal money on abortions.

So, when deciding who to support I want to be sure a candidate understands the implications if they attack Congress and the president, especially when Republicans are in charge. The fact is we have been screwed even by some Democrats. In today’s world, until we get rid of the felon, and Democrats take back both houses of Congress, all of our elected officials, but particularly our mayor, will be walking a tightrope. Beating your chest and attacking what they are doing is not the way to go. Again, we are not in the same position as cities like Portland, Minneapolis, or LA. We saw that again when the courts said the National Guard had to leave those cities, the president couldn’t send them in, but D.C. was exempt from that decision because he can send them here. The president, not the mayor, controls the National Guard in D.C.

Once I am comfortable a candidate understands all that, my criteria for supporting them of course includes many other things. I am a liberal, born in New York City. I taught public school in Harlem and was a member of the teacher’s union. Then went to work for progressive Congresswoman Bella S. Abzug (D-N.Y.). After that, I served as Coordinator of Local Government for the City of New York, during the time of the financial control board there. Then came to D.C. in 1978 to work for the Carter administration. I have been an activist all my life in the areas of civil rights, women’s rights, disability rights, and finally LGBTQ rights. I am a community and Democratic activist. All this impacts my decisions regarding candidates. I want to hear consistency from them. I don’t have a problem with people changing their mind on issues based on principle but do have a problem when it seems like they do so based on which way the wind is blowing. Like those who screamed ‘Defund the Police’ until the community they thought wanted to hear that in D.C. actually told them they wanted more police, not less. They simply wanted them better trained, held more accountable, and more community oriented.

I want a candidate to support statehood for D.C., but while fighting for that, they should speak out for budget and legislative autonomy. They must support mayoral control of the DC National Guard, and a full 4,000 member, well trained, MPD. They must understand how MPD works with federal law enforcement like the FBI, park police, capitol police, and the secret service. They need to reject working with ICE. They need to support more affordable housing, but not city owned housing, which has proven to be a failed experiment. They need to pledge to work to end homelessness providing decent, and available, shelters around the city for both individuals, and families in need. I want a strong education Mayor who supports teachers, and works to expand accountability for charter schools, holding them to the same standards as the public schools. We must have strong programs for both college bound students, and those who want another path, including internships and apprenticeships. Strong support for UDC, healthcare both affordable and available for all, and rental and food assistance when needed. There needs to be a strong focus on reducing the cost of childcare. A focus on the ARTS, libraries, and recreation centers, across all wards of the city. A focus on the environment, and affordable and accessible transportation. Of course, for me it’s a given they must support, and speak out, for the full panoply of rights for the LGBTQ community.

Looking at that list clearly means the city needs to raise the money to pay for all of it. Any candidate running for office who says they don’t support a strong, and vibrant, business sector, is either naïve, or just dumb, and will not have my support. A vibrant business community provides jobs, and in the long run the taxes that pay for the things we all want government to provide.

Once again D.C. is in a different place. We don’t collect taxes from those who work here but live in Maryland or Virginia. So, we have to be smart about the businesses we encourage to locate here and encourage them to hire D.C. residents, who then will pay taxes here. D.C. has developed a strong sports economy. That will be enhanced by the new RFK site, and includes the teams at the Capital Center, Audi Field, and Nats Stadium. Together they bring millions of people into D.C., who spend their money here. When groups like the Working Families Party, who suggest they are anti-business, endorse a candidate, I am wary of that candidate. We can’t be anti-business in D.C. I look at some candidates trying to replicate Mamdani’s victory in New York City by promising the moon. What they don’t seem to realize, or pretend not to, but voters must understand, is we in D.C., our Council and mayor, can’t promise what a New York City mayor does, hoping the governor and Albany, will help him out. In D.C. we don’t have an Albany to help us out. There is no governor coming to the rescue, it’s just us, and what we can negotiate with our Albany, which unfortunately consists of the president and Congress. Some may remember in 1995 we had the Control Board foisted on us. It was lucky at the time the president was a Democrat, Bill Clinton, and he named the board and chair, first Andrew Brimmer, and then the incredible Alice Rivlin. Can you imagine if Congress did that today who Trump would name to control our city?

So, we can’t only dump on them, and attack them, at least the mayor can’t, as she/he/they have to often ask them for help, and stave off their gratuitous attacks. As a columnist, and private citizen, I can attack the felon and his Republican sycophants in Congress all I want, I do and will continue to do so. But those we elect need to understand some constraint. The need to understand sometimes they are walking that tightrope when dealing with the White House and Congress.

I urge everyone to look closely at all the candidates, and then when you decide who you want, make sure you VOTE!

Peter Rosenstein is a longtime LGBTQ rights and Democratic Party activist.

Opinions

The global cost of Trump’s foreign aid ideology

Expanded global gag rule polices people’s identity

U.S. Vice President JD Vance on Jan. 23 announced the new Promoting Human Flourishing in Foreign Assistance Policy. This policy, which has nothing to do with flourishing, is part of the Trump administration’s effort to weaponize U.S. foreign assistance to enforce ideological conformity, to police people’s identity, and to suppress dissent — both at home and abroad.

One of the policy’s three pillars advances a discriminatory framework that denies transgender people’s existence and seeks to censor organizations that affirm transgender people and their rights.

The new policy expands the Mexico City Policy, also known as the global gag rule, which has restricted U.S. foreign aid to non-U.S. civil society organizations providing abortion care under every Republican administration since 1984. What is new — and unprecedented — is the expansion of this rights-restricting logic to efforts addressing gender identity and, more broadly, nondiscrimination efforts.

The new policy also applies to more categories of aid recipients, including multilateral organizations such as UN agencies.

With the expanded global gag rule, the Trump administration seeks to make transgender people invisible globally, as it has within the U.S. Whether it is threatening steep tariffs for countries that resist Trump’s appetite for Greenland, or withholding funds for organizations that refuse to toe the ideological line, the chilling message is clear: standing in the way of the administration’s political or ideological goals will come at a high cost.

Under this rule, organizations risk losing U.S. funding if their activities are seen to fall under the spurious concept of “gender ideology.” Organizations are not allowed to provide, refer for, or support access to gender-affirming care. Neither can they offer accurate information, counseling, or public-facing support for transgender people. The restrictions even apply to cultural activities such as “drag queen workshops, performances, or documentaries.”

Organizations that receive any foreign aid from the U.S. will need to censor themselves, even if their own national or regional laws enable — or oblige — them to speak up for human rights.

This new policy comes after the Trump administration dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development, which has for decades provided the bulk of U.S. international development and humanitarian assistance.

To be clear, LGBT people, regardless of where they are, do not depend on the United States to organize, advocate, and stand up for their rights. And foreign aid is not the answer to undoing global inequity. But the sharp reversal of U.S. foreign policy will have wide-ranging consequences.

For years, protecting the rights of LGBT people had been a core tenet of the U.S. commitment to human rights. U.S. embassies often functioned as safe havens for human rights defenders in places where governments stoked homo- and transphobia for political gain. For LGBT people in the 65 countries that still criminalize same-sex intimacy, civil society-run clinics, supported with U.S. funds, became life-saving spaces — people could get HIV and other care there without fear of being turned away, ridiculed, or reported to the police.

Much of this is progress is now at risk. As a result of the U.S. funding cuts, organizations that directly provided health care and other services for LGBT people were forced to stop services abruptly, cutting off people’s access to chronic medication often without alternative care in place.

The impact extends beyond individual harm. Public health programs by definition are more likely to fail when stigma and fear are institutionalized. Transgender people are among the groups most at risk for ill health precisely because of discrimination and violence.

By prohibiting organizations, from local civil society groups to multilateral organizations like UNAIDS, from affirming transgender identities or addressing these underlying conditions, the expanded global gag rule actively undermines the foundations of effective public health programs.

Under the new and expanded gag rule, organizations face a terrible choice for accepting any U.S. funding. They can either self-censor and stop all work related to transgender people’s rights and needs. Or they forego U.S. funds and risk jeopardizing their organizational survival in an increasingly tough economic and funding climate.

This matters because civil society is one of the few effective counterweights to the global rise of populist and authoritarian governance. Alongside a coordinated global backlash against women’s and LGBT people’s rights are efforts to concentrate power, erode accountability, and close civic space.

Civil society organizations are crucial in exposing and resisting the authoritarian creep and in supporting marginalized groups. Gagging organizations into silence, or hollowing them out through funding cuts, accelerates civic space closure, and strengthens authoritarian governance.

Where the U.S. retreats and bullies, other countries and communities need to step up to offset the funding shortfalls and reduce organizations’ dependency on ideologically restricted U.S. foreign aid.

They need to support marginalized groups, increase funding for civil society groups, and commit funds to bolster multilateral mechanisms such as the Global Fund, which supports funding to combat HIV/AIDS, TB, and Malaria. They should clearly and consistently affirm everyone’s human rights, without exception.

Alex Muller is the director of Human Rights Watch’s LGBT Rights Program.

..

-

Virginia4 days ago

Virginia4 days agoVa. activists preparing campaign in support of repealing marriage amendment

-

Federal Government4 days ago

Federal Government4 days agoTwo very different views of the State of the Union

-

Opinions4 days ago

Opinions4 days agoThe global cost of Trump’s foreign aid ideology

-

Movies3 days ago

Movies3 days agoMoving doc ‘Come See Me’ is more than Oscar worthy