Arts & Entertainment

Dynamic differences

Two brand new organs — two of the world’s best organists — four days in Washington

Ken Cowan, left, and Cameron Carpenter. (Cowan photo by Jim Cunningham, courtesy First Baptist Church; Carpenter photo by Heiko Laschitzki, courtesy Bucklesweet Media)

Pipe organ aficionados in Washington had the opportunity to gorge on an embarrassment of riches over the past few days. On Wednesday, iconoclast Cameron Carpenter played the Kennedy Center. Just four days later, traditionalist Ken Cowan performed at D.C.’s First Baptist Church.

The rare experience of having these two brilliant young organists here so close together was doubled by the fact that both venues in which they played just unveiled massive new organs.

The Rubenstein Family Organ at the Kennedy Center, a $2 million, 85-rank, four manual beauty by Casavant Freres, has 4,972 pipes and replaces the Filene Organ, an Aeolian Skinner from 1972 that was adequate at best. It’s a gift from Kennedy Center chairman David Rubenstein and his wife, Alice.

The new Austin organ at First Baptist is a 118-rank double (chancel and gallery) organ that has about 6,000 pipes and cost roughly $1.8 million. It’s only the second five-manual (i.e. five levels of keyboards) organ in Washington (National City Christian Church — which added to the wealth by hosting the equally good organist Adam Brakel just the week before — has the other) and replaces the church’s woefully underwhelming previous instrument, a relic Moller from 1948 that had just two manuals and about 2,100 pipes.

The new Austin Organ (Op. 2795) at First Baptist Church of Washington. (Blade photo by Joey DiGuglielmo)

The Rubenstein is a full pipe organ; First Baptist’s is majority pipe but is augmented with some digital stops. They’re not the largest organs in Washington — National Cathedral’s 1938 Skinner has 189 ranks and more than 10,647 pipes and the National Shrine’s two Moller organs have a combined 197 ranks and 10,748 pipes; National City’s has 105 ranks and nearly 7,600 pipes. Yet these are still major new additions to the District’s musical landscape. More pipes don’t necessarily mean more sound — just a larger range of tonal variation that’s available.

While both instruments have been previously heard, Carpenter’s program was the first “concert length” recital on the new organ at the Kennedy Center and opens a series that continues with Paul Jacobs — one of a very short list of young organists in the same league as Carpenter and Cowan — on Feb. 5 and Latvian organist Iveta Apkalna on May 21. Despite the Rubenstein organ only having been played publicly a handful of times thus far, it was Carpenter’s second time playing it. He played the fourth movement of Saint-Saens’s “Symphony No. 3 in C minor” (the “organ symphony”) on it with the National Symphony Orchestra on Sept. 29.

And while First Baptist organist/choirmaster Lawrence Schreiber gave the inaugural recital of the Austin organ on Sept. 15, Cowan’s performance this week was the first in the church’s “Distinguished Organist” series, which continues with a performance by Christopher Houlihan on Nov. 24. An hour-long recital featuring several guest players of the region will be held on Halloween at 7 p.m.

The two concerts — equally dazzling — were a study in contrasts, chiefly because of the vast difference of artistic and aesthetic choices from Carpenter, 32, and Cowan, 38. Both played fully from memory save for one short self-composed piece for which Carpenter used a score. Possessed, it appears, of equal talent, Carpenter is a colorful rabble rouser who clearly delights in shaking up the often staid world of organ music. One could never call Cowan staid — he simply lights his musical fires with a different brand of kerosene. His playing is every bit as technically impressive and boundary-pushing as Carpenter’s; he just does it while wearing a tux and in a setting — First Baptist — as traditional (albeit breathtaking) as it gets.

One may be momentarily intrigued by their differences — Cowan’s tux and everyman’s haircut to Carpenter’s Versace, tight leather pants and mohawk, the former’s straight sexual orientation (he’s married to violinist Lisa Shihoten) to the latter’s bisexuality, etc. — and insist only the sounds produced are of consequence, but it’s not that simple, for they’re each having a radically different impact on the world.

Since they’re of roughly equal ability, one quickly realizes there are other factors at play, some musical, some not, just as there were with the late organists Virgil Fox and E. Power Biggs a generation ago. What’s ironic is how the organ world establishment (represented mostly in the U.S. by the American Guild of Organists) now venerates Fox while Biggs is but a footnote. Though Carpenter is often dismissive and indifferent when asked about Fox, it’s always the envelope pushers who are remembered long after their time. It’s amusing to watch these perceptions play out — many U.S. organists, both in church and in academia, are almost contemptuous of Carpenter and only grudgingly acknowledge his technical prowess while Cowan is exalted as one of a precious few heirs apparent.

This isn’t just about hairstyles or even registrations (the settings by which organ sounds are varied throughout a piece or concert), for Cowan’s, while overall less brash than Carpenter’s, are not always as slavishly adhered to as some traditionalists insist (e.g. using only registrations that Bach had at his disposal in the 1700s when playing his works today).

Controversial, outspoken Carpenter is clearly having the overall bigger impact. Touted as “the world’s most visible organist” in the Kennedy Center program, it’s not much of an overstatement if at all. Though his D.C.-area debut at the Strathmore in April had an underwhelming turnout, he filled the orchestra section easily at the 2,400-seat Kennedy Center Concert Hall (the upper tiers were empty). Yes, the tickets were only $15 a piece, but a nearly full house to any organ recital in 2013 is seen as a triumph even if it’s free. Which Cowan’s was, though donations were accepted. The floor of First Baptist, which seats about 800, appeared to be about half full Sunday.

Carpenter’s at times brutal candor equals that of Joni Mitchell. Think for a minute about the overall rigidity of the classical world versus the pop world, and one can imagine the effect this has. Just last week, Carpenter mentioned in passing organ conventions and lamented anyone “unfortunate enough to have to go to one.” The AGO brass sees these as cheap shots and holds grudges accordingly. They’re sharpening their knives now in anticipation of his 2014 unveiling of a Marshall & Ogletree digital touring organ whose development Carpenter — who’s always polite in conversation and more nerdy than punk — supervised. He says it will revolutionize what an organist can do by not forcing an adaptation to site-specific pipe organs. They say there’s no way a virtual instrument can duplicate the richness of a true pipe organ (while Fox toured with electronic organs in the 1970s he never — to my knowledge — claimed they were sonically in the same league as a pipe organ).

There also may be unacknowledged resentment of the amount of world-wide press attention Carpenter gets, which is considerable, perhaps even unprecedented, for an organist. His fame is of rock star proportions in Japan and in parts of Europe.

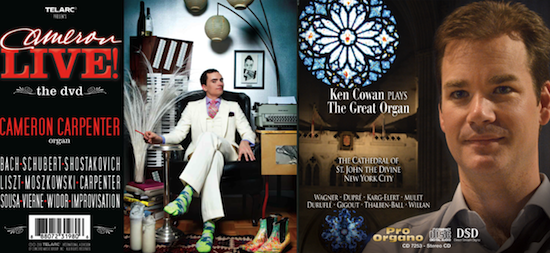

Marketing and presentation are also factors. Carpenter has more media savvy, more acumen at presenting himself as a celebrity. Cowan — more classically handsome than Carpenter but not as trim and buff — looks like a professor (which he is; he heads the organ program at Rice University) who just happens to give recitals on weekends (which he does). Place their latest albums side by side and the photos alone illustrate the difference. Carpenter makes wise use of a stylist and put care into the overall presentations.  Cowan’s looks like an improperly lit snapshot superimposed over a boring church interior. Star power counts for something and Carpenter has it. It’s the difference between, say, a Jane Fonda and a Liv Ullmann. It’s no fluke that Fonda is the household name.

Cowan’s looks like an improperly lit snapshot superimposed over a boring church interior. Star power counts for something and Carpenter has it. It’s the difference between, say, a Jane Fonda and a Liv Ullmann. It’s no fluke that Fonda is the household name.

It was a bit startling then — with all this swirling around the classical music consciousness — how traditionally Carpenter opened his 89-minute Kennedy Center recital with the Bach “trio” Sonata No. 6 in G Major (BWV 530), especially the exquisite first movement (“Vivace”) which sounds as dainty as a finely embroidered doily but is wickedly difficult to play with three contrapuntal lines swirling about (right hand on one manual, left hand another and the pedals/feet sharing an equally complex third voice). Carpenter took it at a very brisk tempo and pulled it off with expected aplomb. He used more pedal 16-foot stops than Bach would have had in his era, but the flute- and principle-heavy registration was not unorthodox. His closing self-added ornamentation — not an unusual thing to do — was a well-placed flourish at the end of a musical sentence.

The registrations were slightly more daring in the languid second movement (“Lento”), which had breathy, deep 16-foot moderately soft pedal stops over which Carpenter wove the melody with slightly louder reed stops. He took the (“Allegro”) third movement in a more traditional manner, giving its lovely contrapuntal interplay the stately feel of a fanfare.

One of the challenges any organist faces is blending the four types of sounds the instrument produces — generally the flutes and strings are softer than the principles and reeds. Building a gradual increase in volume by changing registration can be tough, but Carpenter did so brilliantly (Cowan is also a master of this) in his Etude from the prelude of Bach’s “Cello Suite No. 1,” a piece he also used as an encore in homage to Yo-Yo Ma (who also played that night) during his previous Kennedy Center appearance. It started with a delicate, chiffy pedal solo but climaxed with loud grandiosity.

Its inclusion was a surprise — Carpenter added it after saying he wasn’t finished learning his new composition “Music for an Imaginary Film” which was slated to close the program. In its place he also added his own “Love Song No. 2,” a lush, string-laden contemporary piece he rightly called a palate cleanser.

He closed the first half of the program with an adaptation of Mozart’s “Sonata in D Major” (K.284), which had constant-yet-deft color shifts. He made clever use of some of the organ’s more outré stops with playful little honks and echoes in the third movement, several of which elicited light chuckles from the crowd.

In the second half, Dupre’s “Variations on a Noel, Op. 20” came roaring to life in a way simply not possible when Carpenter performed the piece (one of only two duplicated) at the Strathmore. It was effective there, but if it were possible to hear the two performances side by side, no further arguments would be needed for the sonic chasm that exists between a grand instrument like the Rubenstein organ and the one-dimensional Rodgers electronic Carpenter played there. He performed like a demon that night — changing registrations like a mad scientist (perhaps necessitated by the need for variation on the much smaller organ) — but hearing him at the Kennedy Center was exponentially more satisfying. The Dupre Noel set is a perfect piece for Carpenter giving him enough deliciously weird variations (most of it’s about as warm and Christmasy as a Quentin Tarantino film) to play with. He upped the ante with equally diabolical registration choices, at times summoning what sounded like the gates of hell with the full power of the organ.

If there was any disappointment to the evening, it was only slightly in the sequencing. Building an impossibly overstated introduction to a transcription of Scriabin’s (originally for piano) “Sonata No. 4, Op. 30,” (“I can’t imagine music more uplifting and absolutely affirming of humanity than this,” he said), the piece (originally slated to close the first half) was too dense and abstract to be a wholly satisfying finish to the evening. The heroic, playful and jaunty Tchaikovsky “Scherzo” from “Symphony No. 6,” which Carpenter practically galloped his way through — you can see the music coursing through his gyrations — and used to open the second half, would have been a better choice. Yes, it’s the more ear-friendly and obvious crowd pleasing-kind-of piece, but that’s not why I suggest this. The epic full organ registration with which Carpenter played it sounded so rich and symphonic, one could not possibly fathom that all this sound was coming from one human and one organ. Closing with it would have showed both he and the organ off in the most staggering light.

Two encores — Chopin’s “Minute Waltz” and the bon mot “Stars and Stripes Forever” were everything encores should be: playful, fun, short and easy on the ears.

Cowan, too, opened his 94-minute recital with Bach, hardly surprising but fine. His “Toccata in E Major (BWV 566)” got things off to a solid but far-from-earth-shattering manner. Cowan’s almost non-existent body movement while playing combined with the hardly daring opening — though admittedly no more traditional than Carpenter’s — initially had me fearing we might be in for a long afternoon. I knew Carpenter would shake things up; having not heard Cowan live before, I wasn’t sure where he was heading. Yes, there was a program but the pieces were not, for the most part, staples of the organ repertoire.

To say there was nothing to fear is a vast understatement. Cowan quickly got things bubbling with an utterly transfixing performance of Jean Roger-Ducasse’s “Pastorale,” which he played exquisitely and registered imaginatively and seamlessly.

Ironically considering the sacred setting, the devil was summoned twice — in Rachel Laurin’s playful “Beelzebub’s Laugh,” an etude that Cowan masterfully registered so that a three-note descending melodic line that was repeated many times darted around from the Chancel to the Gallery organs so quickly it was nearly dizzying. Satan was further evoked in an arrangement of Liszt’s famous “Mephisto Waltz No. 1,” a staggerlingly virtuosic piece with which Cowan clearly had fun.

Leo Sowerby’s maddeningly difficult “Pageant,” which opens with a lengthy pedal solo that descends in rapid chromatic lines, found Cowan exhibiting every bit as much elaborate foot work as Carpenter famously exhibits in his transcription of Chopin’s “Revolutionary Etude,” a massive YouTube hit he curiously no longer plays live. While nobody’s calling it a talent competition, the two are clearly equals in technical ability and overall musicianship.

Cowan’s recital came to a glorious and stately climax with Max Reger’s monumental Fantasy on the Chorale “Wachet auf, ruft uns die stimme,” (Op. 52, No. 2), a dramatic interpretation of the famous Advent hymn (“Sleepers Awake”) that breaks into a daring four-part fugue and ends with a towering procession on which Cowan brought the magnificent new organ to full flower. This is another spot that separates the men (state-of-the-art pipe organs) from the boys (the best electronics available): the triple-forte passages on a great organ like the Austin are unquestionably loud but not in an ear-splitting, siren kind-of way. It’s loud in a lush way that still manages to be easy on the ear and with a depth of quality and detail no speaker can summon — nearly the same difference as one perceives optically between a sunset in nature versus one seen on a high definition TV screen. Only having experienced it in nature, can one fully appreciate the difference.

Cowan’s well-deserved encore was another pedal workout — George Thalben-Ball’s “Variations on a Theme by Paganini,” which found him achieving almost unfathomable legato-yet-uber-fast melodic passages on the pedalboard alone.

As one might imagine, these recitals together made for heady experiences. One savored them as one might great multi-course meals from two top-tier chefs working with the crème de la crème of fresh ingredients on two different nights. It’s impossible to overstate their sumptuousness. No degree of rhapsodic waxing feels sufficient.

First Baptist’s organ — some tuning issues evident at Schreiber’s recital all worked out as expected — is not necessarily sonically any richer than that of the Rubenstein organ; it simply has a substantially broader range of sound, which Cowan made abundant use of and of which Carpenter no doubt would have done as well had he performed there. First Baptist’s fills the space perhaps a bit more thoroughly than the Rubenstein, which, though possessing sonic heft, never quite flirts with rumbling the architecture. You don’t quite feel it the way you feel the enveloping Austin.

It was especially noticeable on the Reger during which Cowan spent lengthy measures savoring the organ’s soft 32-foot pedal stops, which rumbled and chiffed — slightly differently even from tone to tone — like warm signals from beneath the ocean floor. Elsewhere, soft string stops in the manuals sounded as warm as finely ground spun sugar. The two magnificent sets of “trompette-en-chamade” stops (one rank softer and in the English trumpet tradition; the other more blaring and French) were repeatedly woven into the selections and used generously but wisely, ringing out from the church balcony where they’re placed.

Perhaps realizing they both had rare opportunities to introduce many to new instruments, Carpenter and Cowan both clearly took delight in showcasing both their own talent and that of the organ builders.

One salivates at the thought of what these two geniuses will do in the coming years, not to mention all the great organists Washingtonians and visitors will enjoy on these stupendous new instruments.

Blade Features Editor Joey DiGuglielmo may be reached at [email protected].

Carpenter’s set list

Sonata No. 6 in G Major (BWV 530) (Bach)

1. Vivace

2. Lento

3. Allegro

4. Etude on the Prelude from Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major (BWV 1007) (Bach)

5. Love Song No. 2 (Carpenter)

Sonata in D Major (K. 284) (Mozart)

6. Allegro

7. Rondo and Polonaise

8. Theme with Variations

Intermission

9. Scherzo from Symphony No. 6 “Pathetique” (Tchaikovsky)

10. Variations on a Noel (Op. 20) (Dupre)

Sonata No. 4 (Op. 30) (Scriabin)

11. Andante

12. Prestissimo Volando

Encores

13. Minute Waltz (Chopin)

14. Stars and Stripes Forever (Sousa)Cowan’s set list:

1. Toccata in E Major (BWV 566) (Bach)

2. Pastorale (Roger-Ducasse)

3. Beelzebub’s Laugh (Etude-Caprice, Op. 66) (Laurin)

4. Pageant (Sowerby)

Intermission

5. Mephisto Waltz No. 1 (Liszt)

6. Fantasy on the chorale “Wachet auf, ruft uns die stimme” (Op. 52, No. 2) (Reger)

Encore

7. Variations on a Theme by Paganini: a Study for the Pedals (Thalben-Ball)

Highball Productions held performances of a drag musical, ‘Defrosted,’ at JR.’s on Friday and Saturday.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

Movies

Intense doc offers transcendent treatment of queer fetish pioneer

‘A Body to Live In’ a fascinating trip into a transgressive culture

Once upon a time in the 1940s, a teenager named Roland Loomis, who lived with his devout Lutheran parents in Aberdeen, S.D., received a hand-me-down camera from his uncle. It was a gift that would change his life.

Small and effeminate, he didn’t exactly fit with the “in” crowd of his small rural town; but he had an inner life more thrilling than anything they had to offer, anyway, and that camera became the key with which it could finally be unlocked. Waiting patiently for those precious hours when he was alone in the house, he used it to capture images of himself that expressed an identity he had only begun to explore, through furtive experiments in body manipulation that incorporated exotic costuming, erotic nudity, gender ambiguity, and what many of us might call (though he would not) self-mutilation, including the piercing of his skin and other extreme forms of physical modification.

Young Roland would go on to become famous (or perhaps, notorious) in the decades to come, but it would be under a different name: Fakir Musafar, the focal figure of filmmaker Angelo Madsen’s documentary “A Body to Live In,” which opened in Los Angeles on Feb. 27 and expands to New York this weekend.

Like Musafar himself, who died of lung cancer at 87 in 2018, it’s a documentary that doesn’t quite follow the expected rules. Eschewing “talking head” commentators and traditional narration, Madsen spins his movie from his subject’s extensive archives and allows the information to come through the voices of those who were close to him: collaborator and life partner Cléo Dubois, performance artists Ron Athey and Annie Sprinkle, and underground publisher V. Vale are among the many who contribute their memories and impressions of him, while evocative photos and film footage create a hazy “slide show” effect to provide a guided tour of his life, his art, and his legacy. Less a biography than a chronicle of profoundly unorthodox self-discovery, it details his development from those early days of clandestine self-photography through a continual evolution that would see him become a performance artist, a central figure in the burgeoning BDSM culture, a seeker who espoused eroticism as a spiritual practice, the founder of a “Radical Faeries” offshoot for the kink/fetish community, and ultimately an elder and mentor for a new generation for whom his once-taboo ideas and explorations had essentially become mainstream – thanks in no small part to his own pioneering efforts.

It’s a fascinating, hypnotic trip into a culture which might feel disturbingly transgressive to those who have never been a part of it – yet will almost certainly feel like being “seen” to those who have. It opens a window into a lifestyle where leather, kink, BDSM, gender play, and non-monogamous “situationships” are not just accepted but viewed as natural variations on the spectrum of human sexuality; and in the middle of it all is Musafar, on a deeply personal quest to connect with the deepest part of his essence through the intense and ritualistic pursuit of an inner drive that keeps pushing him further. As one reminiscing cohort remarks during the film, it’s as if he is “trying to find an answer to a question that” he “cannot form.”

Indeed, it might be said that Madsen’s movie is an exercise in forming that question; bringing his own “transness” into the mix as he examines the various aspects of Musafar’s ever-evolving relationship with self, identity, and presentation, he evokes a timely resonance in which the imperative to make physical form match psychic self-perception becomes an irresistible force, and draws a direct line between his subject’s fluid ambiguity and the plight faced by modern trans people over the bigotry of those who think gender is strictly about genitalia. Perhaps the question has to do with whether we are defined by our identities or by our physical form – or if both are malleable, adaptable, and in a constant state of flux.

In any case, with regard to Musafar, “A Body to Live In” is unquestionably a film about transformation, not just of physical manifestation but of consciousness itself. In his journey from being little Roland, the outcast schoolboy with a secret fetish, to Fakir, the spiritual psychonaut for whom sex and gender are only walls that separate us from a true and eternal essence, he is embodied by Madsen’s reverent documentary as a being in the process of breaking free from the restrictions of physical existence, of transcending all such distinctions by letting go of life itself – something underscored not only by the section of the movie dealing with the impact of the AIDS epidemic on Musafar’s deeply-bonded community, but by his own words, spoken in a deathbed interview that serves as a connecting thread throughout the film. We are kept unavoidably aware of the mortality which – for Musafar at least – seems little more than a prison that keeps us from the unfettered joy of our true nature.

But while Madsen honors his subject as a pillar – and an under-sung hero – of contemporary queer culture, he also addresses the aspects that made him a “problematic” figure; in his life, he drew criticism over perceived cultural appropriation from the indigenous American tribes whose sacred rituals inspired the kink-flavored practices which facilitated his own spiritual odyssey, and which he popularized among his own acolytes to give rise to the still-controversial “Modern Primitive” movement that has been criticized by some for turning meaningful cultural traditions into an excuse for trendy fashion accessories. Even Musafar’s survivors, whose love for him exudes palpably from the stories and memories they share of him throughout the film, make observations that point to his flaws; yet at the same time, Madsen’s documentary makes clear that Musafar himself never saw himself as perfect, either – just as someone willing to endure the kind of suffering that most of us might find unbearable in order to get closer to perfection.

Of course, it probably helped that he enjoyed that so-called “suffering,” but that’s perhaps too glib an observation in the face of a film that so clearly makes a case for the deep and sincere commitment he held for his quest for transcendence; but it’s also a helpful reminder that his practices – which might seem macabre and twisted to the uninitiated – were also an experience of joy, an exercise in rising above pain and making it a vehicle toward enlightenment, and in achieving a deeper understanding of one’s own place in this confusing place we call the universe.

Full disclosure: “A Body to Live In” is an intense experience, replete with candid sexual conversation, frequent nudity, and graphic scenes of extreme fetish practices – like suspension by metal hooks through the skin – which might be hard to handle for those who are unprepared to be confronted by them. Even so, as dark and menacing as it might be for the squeamish outsider, the world revealed in Madsen’s eloquent portrait is full of treasures and steeped in dark beauty, and it’s hard to imagine a more fitting way than that to portray a queer pioneer like the former Roland Loomis.

Nightlife

In D.C. comedy, be sure to shop local

A thriving patchwork of queer-friendly stages in Washington, Baltimore

Most people know stand-up comedy from Netflix specials or late-night sets on Comedy Central. The reality is far different for local working comics like me. A few times a month, I might get paid $50 for a 10-minute set and my photo on a bar flyer to show off to the ladies in my scrapbooking club.

Still, it’s a joy sharing laughs about my well-worn Washington career arc — from conservative reporter to openly trans organic grocery store worker and nightclub comedian. Or, as I like to say onstage, from Fox to foxy.

Stand-up is hard. Offstage, it’s even harder. It took more than a year and nearly 80 open mics to land my first paid set. Since then, I’ve performed in coffee shops, bars, restaurants and even on a city sidewalk. I once performed in the Catskills, which felt like a big deal — even if it was a bigger deal in the 1950s.

As an older trans comic in Washington, I’ve found it nearly impossible to get stage time — or even the courtesy of a returned email — at the big, corporate-owned comedy clubs. Fortunately, there’s a thriving patchwork of queer-friendly producers in Washington and Baltimore creating shows that reflect the diversity of our communities, instead of straight male-dominated lineups that look like the cast of “Ice Road Truckers.”

“There are so many kinds of funny people, but a lot of barriers exist for women and queer people because it’s a very masculine culture,” said Dana Fleitman, who runs the Just Kidding Comedy Collective and is helping produce the Woke Mob Comedy Festival in April, featuring many women and queer comics.

Full disclosure: I’m not performing in the festival. But I am proud to be one of more than 50 women and nonbinary comics Fleitman and her colleagues have helped “train up” through an incubator program she first ran through Grassroots Comedy and now through Just Kidding Comedy Collective.

Another trans comic, Charlie Girard, who splits time between New York and Washington, runs an incubator program called Queers Can’t Take a Joke. He has trained more than 100 comics in Washington.

Girard has one rule: no punching down.

“The best comics speak truth to power,” Girard said. “Making fun of marginalized communities is simple lazy writing based on tired, old stereotypes.”

Ultimately, Girard wants to prepare students not just for queer rooms, but to find their voice and expand into all kinds of spaces.

Comics trained by Girard and Fleitman have gone on to produce or help run shows like Clocked Comedy, Backbone Comedy, the Crackin’ Up open mic and Funny Side Up. Several have found a home on Barracks Row at As You Are — one of my favorite places to perform. In Washington, comic Jenny Cavallero’s show Seltzer is a sober comedy night frequently featuring local queer comics.

In Washington, performer and producer Arzoo Malhotra, who runs Zoo Animal Productions, said it’s a critical moment to support community-based comedy producers, often the first hit by worsening economic conditions.

“We’re losing spaces faster than we’re creating them,” Malhotra said. “We are in the use-it-or-lose-it stage. If there’s a restaurant you like or a performer you want to keep seeing, patronize them now — because they’re going away.”

I’m also grateful for producers in Baltimore, which has a thriving queer comedy scene. Comic Hannah Alden Jeffrey’s monthly “The Really Cool Open Mic,” created for women and trans performers but open to all, regularly draws up to 100 people.

Hannah’s mic and Kenny Rooster’s “Dramedy” open stage have provided safety and opportunity when other stages felt out of reach. Comedians Michael Furr and Jake Leizear also produce shows regularly featuring queer comics.

“We started the REALLY COOL Open Mic because every other mic in town catered toward straight dudes that dominated the Baltimore scene,” Alden Jeffrey said. “Contrary to the lineups of many shows today, people don’t want to see a show of eight guys being bigots. Go figure.”

One of the most important moments for me came when I attended a free showcase at a well-known Adams Morgan club. Like other big venues, it hadn’t responded to emails from a new comic looking for a shot. I sat in the back row thinking maybe these comics were just way funnier than I am.

Then a straight male comedian — with hair even more gorgeous than mine — launched into a long joke comparing eating pizza to performing oral sex on a woman.

At that moment, I walked out feeling better about myself. I remember thinking: nope. I absolutely deserve to be on that stage, too.

Lots of us do.

Jamie Mack is a stand up comedian, speaker and writer. Follow them on Instagram at @jamiemack_blt or email [email protected].