National

Anti-gay violence, domestic abuse on the rise: report

New study, presented to White House, outlines challenges for LGBT victims

Anti-gay violence is increasing by staggering percentages each year, domestic violence among same-sex couples is as pervasive as it is among opposite-sex couples and mainstream service providers for victims of violence are woefully undertrained in how to effectively treat LGBT victims who turn to them for help, according to a new study conducted last year and released in late March.

“Why it Matters: Rethinking Victim Assistance for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Victims of Hate Violence & Intimate Partner Violence” is a joint policy report by the National Center for Victims of Crime and the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs. The Coalition focuses on LGBT and HIV-affected communities. The Center isn’t LGBT specific but bills itself as the country’s leading resource and advocacy organization dedicated to helping victims of crime rebuild their lives. The groups collaborated to identify and raise awareness about the gaps in LGBT victims’ rights (find the report online at ncvc.org or avp.org).

“The collaboration was very deliberate,” says Sharon Stapel, a lesbian and executive director of the New York City Anti-Violence Project, the group that coordinates the Coalition. “The NCVC membership had access to our LGBT expertise and the Coalition membership had access to the Center’s resources. It really began because we knew a lot of this information anecdotally but we didn’t have numbers or know why.”

The study, in which 648 responders from across the country in a variety of victim assistance programs participated voluntarily, found that their agencies lacked outreach to LGBT victims, lacked staff LGBT-specific cultural competency training, did not implement LGBT-specific victim services policies and practices and did not collaborate with those who had, and were under-resourced to correct the barriers to LGBT-specific services.

But how pressing is the need? According to Coalition numbers for 2008, the most recent year for which numbers are available, hate violence against LGBT people is continually on the rise having increased 26 percent from 2006 to 2008 with a 36 percent climb in crimes committed by strangers, a 48 percent increase in bias-related sexual assault and an all-time high rate of hate violence resulting in murder. Anti-LGBT bias-related physical abuse at the hands of law enforcement personnel increased a whopping 150 percent from 2007 to 2008, the Coalition reports.

It also cites several studies from the ’00s that show intimate partner violence affects LGBT couples at the same rate it occurs in straight relationships — between 25 and 33 percent of all relationships. About 11 percent of women reported being raped by their lesbian partners while another study found 39 percent of gay men reported some form of battery from their same-sex partners over a five-year period.

So even though the rates are about the same gay and straight, heterosexual victims tend to have many more resources at their disposal. Gay men who flee abusive partners often find shelters only admit women. Lesbians who turn to shelters are sometimes harassed by the straight women there or worse, discover there’s no barrier in place to prevent their abusive female partners from joining them at the shelter.

Kelcie Cooke is bi and provides trauma counseling at Boston’s Fenway Community Health Center, one of only 36 LGBT-specific victim assistance providers in the U.S. She says fundamental shifts need to happen before mainstream providers are equipped to help LGBT victims.

“The definition of domestic violence is really rooted in the feminist movement,” Cooke says, “which understood it to be about men’s oppression over women. That doesn’t make sense for an LGBT program and under that paradigm, we don’t even see LGBT examples when it’s all about men and women.”

Many other factors often prevent LGBT domestic violence victims from finding help or even reporting their crimes, the report says. Some fear being outed and perhaps losing their jobs if they’re in the military for instance. Others fear being excluded from their circle of friends if a restraining order is granted. Transgender victims face even further obstacles.

Jeff Dion, executive director for the National Center for Victims of Crime, remembers one case he worked on in Miami that illustrated the problem.

“Sometimes law enforcement and the courts don’t take these issues seriously,” Dion, who’s gay, says. “Miami even has its own special domestic violence court but I remember one lawyer advocate who said, ‘You’re going to have a hard time getting justice if a man goes to court dressed as a woman.’ So there are still major barriers to overcome just to treat people like people.”

Morgan Lynn, a local lesbian attorney who founded an LGBT-specific program at Women Empowered Against Violence, says there are further complications she sees daily in her work.

“The people I see are just going to have different issues,” she says. “We have custody issues that affect us differently, marriage and divorce, outing is a whole issue that’s unique to our community. These are just the kinds of questions that straight folks, straight women, just don’t have to be aware of. Like with divorce. There’s no residency requirement to get married in Massachusetts but there is for divorce. So what are you going to do? Move there with an abusive partner just so you can get divorced?”

Homophobia and heterosexism are also challenges, the study says.

“There’s a lot of heterosexism in domestic violence work in general,” Lynn says. “You think about the images you see. A straight woman, she’s probably white, cowering in the corner. Advocates like us try to work through those cultural stereotypes because we know not all abusers are men, or not all abusers are the more masculine person. People think the butch in a lesbian relationship is the abuser but that’s not always the case. I’ve even had some women leave abusive heterosexual relationships thinking there was no domestic violence among lesbians only to find their girlfriend is abusive.”

But there is good news. Many of the mainstream providers who responded said they’d welcome LGBT-specific training.

“We weren’t surprised to hear that but it was gratifying to see the numbers of mainstream service providers who were so vocal about really wanting to do this work but really needing the technical assistance to do it properly,” Stapel says.

Cooke, though, says it requires more than an afternoon training session.

“We’ve done a lot of training here in the Boston area with many front-line workers,” she says. “They’re very well intentioned, but they often don’t have the institutional buy in to really make the changes necessary to do the work correctly. There’s a lot to it. Forms need to be changed for gender variance, they don’t screen at shelters to keep same-sex perpetrators from finding their victims there … there really has to be structural change. It’s not just about sensitivity training.”

So what’s the answer? The study’s authors included several recommendations based on their findings. They advocate collaborations between LGBT-specific and mainstream victim assistance providers, advocacy for state and federal protections to ensure LGBT victims have equal access to protections, an increase of public awareness of the extent and impact of victimization in the LGBT community and increases of funding to see these objectives through.

The two organizations that performed the study are off to a good start — just last week they presented the report at the White House to several of President Obama’s advisers.

“It might take a year or so for this to get into the next round of grant solicitations and to develop grant programs but there’s an awful lot of buzz about this and people are interested and excited to see the report, particularly in this administration,” Dion says. “It’s really helped us quantify the anecdotal evidence. We can now offer the report to validate that and give us a platform to move forward.”

Massachusetts

EXCLUSIVE: Markey says transgender rights fight is ‘next frontier’

Mass. senator, 79, running for re-election

For more than half a century, U.S. Sen. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) has built a career around the idea that government can — and should — expand rights rather than restrict them. From pushing for environmental protections to consumer safeguards and civil liberties, the Massachusetts Democrat has long aligned himself with progressive causes.

In this political moment, as transgender Americans face a wave of federal and state-level attacks, Markey says this fight in particular demands urgent attention.

The Washington Blade spoke with Markey on Tuesday to discuss his reintroduction of the Trans Bill of Rights, his long record on LGBTQ rights, and his reelection campaign — a campaign he frames not simply as a bid for another term, but as part of a broader struggle over the direction of American democracy.

Markey’s political career spans more than five decades.

From 1973 to 1976, he served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, representing the 16th Middlesex District, which includes the Boston suburbs of Malden and Melrose, as well as the 26th Middlesex District.

In 1976, he successfully ran for Congress, winning the Democratic primary and defeating Republican Richard Daly in the general election by a 77-18 percent margin. He went on to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives for nearly four decades, from 1976 until 2013.

Markey in 2013 ran in the special election to fill an open Senate seat after John Kerry became secretary of state in the Obama-Biden administration. Markey defeated Republican Gabriel E. Gomez and completed the remaining 17 months of Kerry’s term. Markey took office on July 16, 2013, and has represented Massachusetts in the U.S. Senate ever since.

Over the years, Markey has built a reputation as a progressive Democrat focused on human rights. From environmental protection and consumer advocacy to civil liberties, he has consistently pushed for an expansive view of constitutional protections. In the Senate, he co-authored the Green New Deal, has advocated for Medicare for All, and has broadly championed civil rights. His committee work has included leadership roles on Senate Foreign Relations Committee and the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee.

Now, amid what he describes as escalating federal attacks on trans Americans, Markey said the reintroduction of the Trans Bill of Rights is not only urgent, but necessary for thousands of Americans simply trying to live their lives.

“The first day Donald Trump was in office, he began a relentless assault on the rights of transgender and nonbinary people,” Markey told the Blade. “It started with Executive Order 14168 ‘Defending women from gender ideology extremism and restoring biological truth to the federal government.’ That executive order mandates that federal agencies define gender as an unchangeable male/female binary determined by sex assigned at birth or conception.”

He argued that the executive action coincided with a sweeping legislative push in Republican-controlled statehouses.

“Last year, we saw over 1,000 anti trans bills across 49 states and the federal government were introduced. In January of 2026, to today, we’ve already seen 689 bills introduced,” he said. “The trans community needs to know there are allies who are willing to stand up for them and affirmatively declare that trans people deserve all of the rights to fully participate in public life like everyone else — so Trump and MAGA Republicans have tried hard over the last year to legislate all of these, all of these restrictions.”

Markey said the updated version of the Trans Bill of Rights is designed as a direct response to what he views as an increasingly aggressive posture from the Trump-Vance administration and its GOP congressional allies. He emphasized that the legislation reflects new threats that have emerged since the bill’s original introduction.

In order to respond to those developments, Markey worked with U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) to draft a revised version that would more comprehensively codify protections for trans Americans under federal law.

“What we’ve added to the legislation is this is all new,” he explained, describing how these proposed protections would fit into all facets of trans Americans’ lives. “This year’s version of it that Congresswoman Jayapal and I drafted, there’s an anti-trans bias in the immigration system should be eliminated.”

“Providers of gender affirming care should be protected from specious consumer and medical fraud accusations. The sexual and gender minority research office at the National Institutes of Health should be reopened and remain operational,” he continued. “Military discharges or transgender and nonbinary veterans and reclassification of discharge status should be reviewed. Housing assignments for transgender and nonbinary people in government custody should be based on their safety needs and involuntary, solitary or affirmative administrative confinement of a transgender or nonbinary individual because of their gender identity should be prohibited, so without it, all of those additional protections, and that’s Just to respond to the to the ever increasingly aggressive posture which Donald Trump and his mega Republicans are taking towards the transgender.”

The scope of the bill, he argued, reflects the breadth of challenges trans Americans face — from immigration and health care access to military service and incarceration conditions. In his view, the legislation is both a substantive policy response and a moral declaration.

On whether the bill can pass in the current Congress, Markey acknowledged the political hardships but insisted the effort itself carries as much significance as the bill’s success.

“Well, Republicans have become the party of capitulation, not courage,” Markey said. “We need Republicans of courage to stand up to Donald Trump and his hateful attacks. But amid the relentless attacks on the rights and lives of transgender people across the country by Trump and MAGA Republicans, it is critical to show the community that they have allies in Congress– the Trans Bill of Rights is an affirmative declaration that federal lawmakers believe trans rights are human eights and the trans people have the right to fully participate in public life, just like everyone else.”

Even if the legislation does not advance in this congress, Markey said, it establishes a framework for future action.

“It is very important that Congresswoman Jayapal and I introduce this legislation as a benchmark for what it is that we are going to be fighting for, not just this year, but next year,” he said when asked if the bill stood a legitimate chance of passing the federal legislative office when margins are so tight. “After we win the House and Senate to create a brand new, you know, floor for what we have to pass as legislation … We can give permanent protections.”

He framed the bill as groundwork for a future Congress in which Democrats regain control of both chambers, creating what he described as a necessary roadblock to what he views as the Trump-Vance administration’s increasingly restrictive agenda.

Markey also placed the current political climate within the longer arc of LGBTQ history and activism.

When asked how LGBTQ Americans should respond to the removal of the Pride flag from the Stonewall National Monument — the first national monument dedicated to recognizing the LGBTQ rights movement — Markey was unwavering.

“My message from Stonewall to today is that there has been an ongoing battle to change the way in which our country responds to the needs of the LGBTQ and more specifically the transgender community,” he said. “When they seek to take down symbols of progress, we have to raise our voices.”

“We can’t agonize,” Markey stressed. “We have to organize in order to ensure that that community understands, and believes that we have their back and that we’re not going away — and that ultimately we will prevail.”

Markey added, “That this hatefully picketed White House is going to continue to demonize the transgender community for political gain, and they just have to know that there’s going to be an active, energetic resistance, that that is going to be there in the Senate and across our country.”

Pam Bondi ‘is clearly part’ of Epstein cover up

Beyond LGBTQ issues, Markey also addressed controversy surrounding Attorney General Pam Bondi and the handling of the Epstein files, sharply criticizing the administration’s response to congressional inquiries.

“Well, Pam Bondi is clearly part of a cover up,” Markey said when asked about the attorney general’s testimony to Congress amid growing bipartisan outrage over the way the White House has handled the release of the Epstein files. “She is clearly part of a whitewash which is taking place in the Trump administration … According to The New York Times, Trump has been mentioned 38,000 times in the [Epstein] files which have been released thus far. There are still 3 million more pages that have yet to be released. So this is clearly a cover up. Bondi was nothing more than disgraceful in the way in which she was responding to our questions.”

“I think in many ways, she worsened the position of the Trump administration by the willful ignoring of the central questions which were being asked by the committee,” he added.

‘I am as energized as I have ever been’

As he campaigns for reelection, Markey said the stakes extend beyond any single issue or piece of legislation. He framed his candidacy as part of a broader fight for democracy and constitutional protections — and one that makes him, as a 79-year-old, feel more capable and spirited than ever.

“Well, I am as energized as I have ever been,” he said. “Donald Trump is bringing out the Malden in me. My father was a truck driver in Malden, Mass., and I have had the opportunity of becoming a United States senator, and in this fight, I am looking ahead and leading the way, affirming rights for the trans community, showing up to defend their rights when they are threatened from this administration.”

He continued, reiterating his commitment not only to the trans community but to a future in which progressive and proactive pushes for expanded rights are seen, heard, and actualized.

“Our democracy is under threat from Donald Trump and MAGA Republicans who are trying to roll back everything we fought for and threaten everything we stand for in Massachusetts, and their corruption, their greed, their hate, just make me want to fight harder.”

When asked why Massachusetts voters should reelect him, he said his age and experience as a 79-year-old are assets rather than hindrances.

“That’s exactly what I’m doing and what I’m focused upon, traveling across the state, showing up for the families of Massachusetts, and I’m focused on the fights of today and the future to ensure that people have access to affordable health care, to clean air, clean water, the ability to pay for everyday necessities like energy and groceries.”

“I just don’t talk about progress. I deliver it,” he added. “There’s more to deliver for the people of Massachusetts and across this country, and I’m not stopping now as energized as I’ve ever been, and a focus on the future, and that future includes ensuring that the transgender community receives all of the protections of the United States Constitution that every American is entitled to, and that is the next frontier, and we have to continue to fight to make that promise a reality for that beleaguered community that Trump is deliberately targeting.”

National

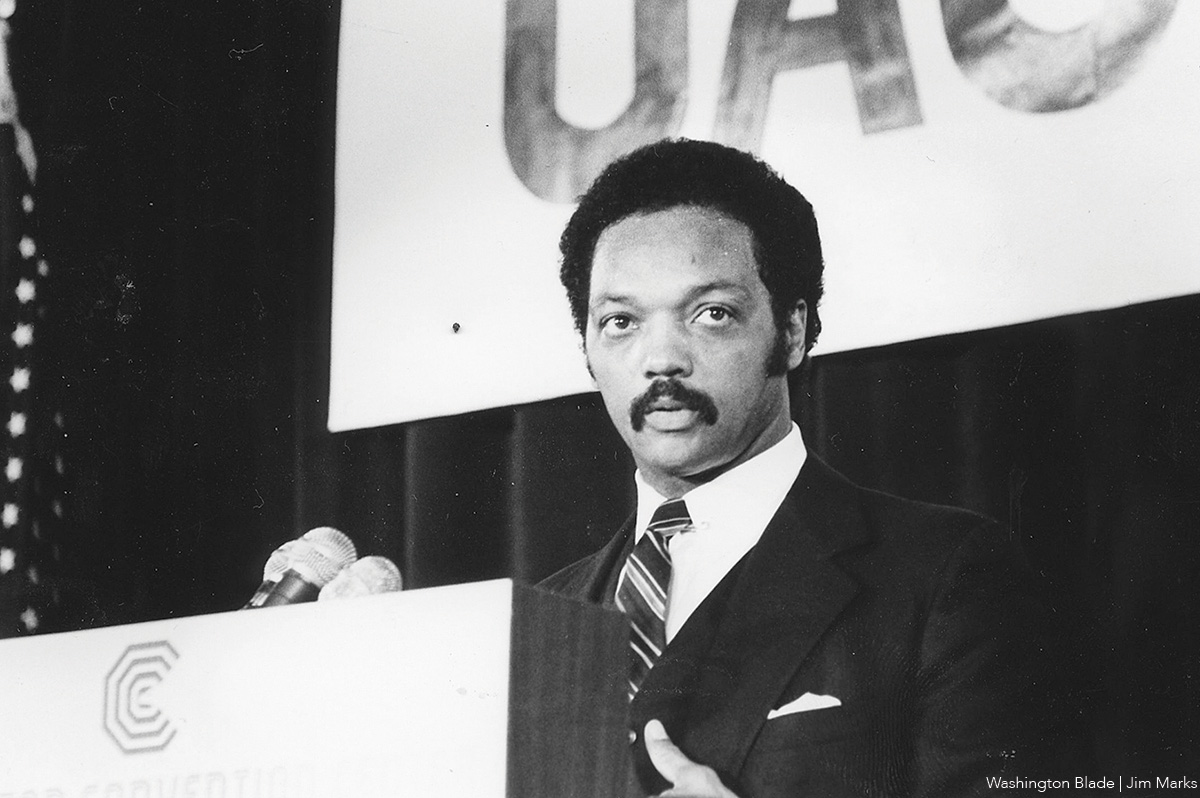

LGBTQ activists mourn the Rev. Jesse Jackson

Prominent civil rights leader died on Tuesday at 84

LGBTQ rights advocates have joined the nation’s civil rights leaders in reflecting on the life and work of the Rev. Jesse Jackson, the famed U.S. civil rights leader whose family announced passed away on Feb. 17 at the age of 84.

Known as a follower and associate of African American civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Jackson emerged in the 1960s as a leading civil rights advocate for the Black community and other minorities for decades throughout the U.S., including in Washington.

In a less known aspect of Jackson’s involvement in politics, following his campaigns for U.S. president in 1984 and 1988, Jackson won election in 1990 as the District of Columbia’s shadow senator, a ceremonial position created to lobby Congress for D.C. statehood.

Jackson, who at that time had a home in D.C., received strong support from D.C. voters, including LGBTQ voters who became aware of Jackson’s support for LGBTQ issues. He served just one six-year term as the city’s shadow senator before choosing not to run again.

An early supporter of marriage equality, Jackson was among the prominent speakers at the 1987 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Jackson joined other speakers at a rally on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol.

During his run for president in 1988 the D.C. Gertrude Stein Democratic Club, an LGBTQ group that has since been renamed the Capital Stonewall Democrats, endorsed Jackson for president ahead of the city’s Democratic presidential primary.

“The fight for justice requires courage, hope, and a relentlessness that will not be denied. Rev. Jesse Jackson embodied that fight every day,” said Kelley Robinson, president of the Human Rights Campaign, the nation’s largest LGBTQ advocacy organization.

“From disrupting political systems and building people power to helping this country imagine a freer future for all of us, Rev. Jackson was a force,” Robinson said in a statement. “His historic presidential campaigns paved the way for generations of Black leaders to imagine ourselves in rooms we were once told were closed to us.”

Robinson added, “Reverand Jackson also stood up when it mattered; when it wasn’t easy and when it wasn’t popular. His support for marriage equality and for LGBTQ+ people affirmed a simple, powerful truth: our liberation is bound together.”

She also pointed to Jackson’s support for efforts to repeal California’s Proposition 8, a 2008 referendum passed by voters to ban same-sex marriage in the state.

“Marriage is based on love and commitment, not on sexual orientation. I support the right for any person to marry the person of their choosing,” Robinson quoted Jackson as saying in support of efforts that succeeded in overturning the California marriage ban.

The national organization PFLAG, which represents parents, friends, and allies of the LGBTQ community, released a statement from its president, Brian K. Bond, citing Jackson’s longstanding support for the LGBTQ community.

“Today, as we learn of the passing of Rev. Jesse Jackson, we mourn the loss of a giant among us,” Bond said in the statement. “When many refused to acknowledge the existence and struggles of LGBTQ+ people, Rev. Jackson saw us, affirmed us, and demanded equality inclusively,” Bond said. “In his address to the Democratic National Convention in 1984, Rev. Jackson named us specifically as part of the fabric of the American Quilt,” Bond says in his statement.

The statement adds, “He has shown up for and marched with the LGBTQ+ movement through the AIDS crisis, marriage equality, and ever after. Rev. Jackson’s leadership and allyship for LGBTQ+ people will be felt profoundly by his PFLAG family. We will continue to honor his legacy as we continue to strive to achieve justice and equality for all.”

D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser, citing Jackson’s role as a D.C. shadow senator, said for many in the country, Jackson “was the first person they heard make the case for D.C. statehood. The first person they heard say: it’s the right thing to do.”

Bowser added, “In 1988, he said that we were at a crossroads, and he posed this question: Shall we expand, be inclusive, find unity and power; or suffer division and impotence? It is a question as relevant today as when he asked it,” the mayor said, “And in Rev. Jackson’s name and memory, we must continue fighting for the answer we know our nation deserves.”

D.C. Congressional Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton (D) said she was honored to have worked with Jackson during his tenure as D.C. shadow senator and throughout his years as a civil rights advocate.

“From the front lines of the civil rights movement to national campaigns that expanded the political imagination of this country, Jesse Jackson lifted up the voices of those too often unheard,” Norton said in a statement. “He turned protest into progress and transformed moral conviction into political action”

According to Norton, “His work-built bridges across race, class, and geography, helping redefine what inclusive democracy could look like in America.”

National

Trump falsely links trans people to terrorism

Intelligence agencies threatening to investigate community members as domestic terrorists

Uncloseted Media published this article on Feb. 14.

By HOPE PISONI | In December, Kathy Brennan was in San Francisco on a video call with her wife and son when she started to feel a burning pain in her chest. While she ignored it at first, it quickly spread to more of her body until it was too much to bear. She called 911 and was brought to the hospital on a stretcher.

“My entire chest was just crushed in pain, I couldn’t even move it was so bad,” Brennan told Uncloseted Media. “I said ‘God, I am not ready to die here. Please don’t let me die.’ I was thinking about Alaina, and we have so much more life together.”

Brennan spent the next few days recovering in the hospital from what doctors determined to be a stress-induced heart attack.

Brennan had spent the past year in a near-constant state of what she called “safety monitoring” her wife, Alaina Kupec.

She obsessively followed the news about the Trump administration’s attacks against the trans community, especially as officials began openly labeling trans people as terrorists. Everywhere she went, she mentally patrolled for how to keep her wife safe.

“Is our home safe? Is my wife safe? Are we safe? What do we have to do? … Can we protect ourselves if people come to our door? What do we have to worry about when we go to the grocery store? Are we gonna get doxxed?” Brennan remembers thinking.

Kupec, a trans naval intelligence veteran, is an outspoken advocate for trans rights and is the founder president of Gender Research Advisory Council + Education (GRACE).

“I think the big worry is that she will be taken away from me and we won’t be able to find her. … Then, just for the sheer sake of cruelty, my beautiful, feminine woman of a wife, they would put her in a men’s prison.”

Brennan’s fear reflects that of many trans Americans and their loved ones. In the aftermath of the assassination of anti-trans conservative activist Charlie Kirk, the Trump administration and its allies began taking actions to target socially progressive people and organizations as terrorists, with a focus on trans people. In September, Trump signed an executive order designating Antifa, a decentralized movement focused on militant opposition to fascism, as the first ever “domestic terrorist organization.” At the same time, the closely allied Heritage Foundation — who penned Project 2025 — began pushing for the creation of a new national security designation called “Transgender Ideology-Inspired Violent Extremism.”

Shortly after, Trump released National Security Presidential Memorandum (NSPM)-7, which directs intelligence agencies to investigate left-wing political organizations for involvement in domestic terrorism, singling out “extremism on migration, race, and gender” and “hostility towards those who hold traditional American views on family, religion, and morality.”

The unfounded trans terrorism panic has swept right-wing spaces, and experts say that it’s putting trans people in danger.

“If people are told, day after day, especially from … people with that veneer of legitimacy, that this entire group of people … is implicitly a dangerous terrorist, that sends that message that these people are able to be targeted for violence,” Jon Lewis, a research fellow at the Program on Extremism at George Washington University, told Uncloseted Media.

The what and the why

While Trump relied on anti-trans messaging since he began campaigning in the 2024 presidential election, his portrayal of trans people as a national security threat emerged in response to an August 2025 mass shooting in Minneapolis, where a trans person killed two children. While the overwhelming majority of mass shooters are cisgender men, right-wing figureheads blamed the shooting on the perpetrator’s transness.

While Kirk’s assassin is cisgender, early reports falsely claimed that he had engraved pro-trans messages onto his bullets, which conservative figures like Megyn Kelly and Laura Loomer used to blame trans people for the killing. “It’s time to designate the transgender movement as a terrorist movement,” Loomer said the following weekend on X. And Vice President JD Vance suggested that he considers trans people to be part of a “terrorist movement.”

The Trump administration picked up on this rhetoric to justify its actions: the Antifa executive order and NSPM-7 both reference Kirk’s assassination as well as either trans people or “extremism on gender.”

As these policies began rolling out, independent journalist Ken Klippenstein reported that the FBI was preparing to designate trans people as “nihilistic violent extremists.” A leaked intelligence brief showed that U.S. Customs and Border Protection had centered the focus of one extremist group on their trans membership, referring to them as a “radical leftist trans militant cult.”

How these actions will be enforced remains to be seen. At least two trans women are currently jailed and awaiting trial over an anti-ICE protest where a local police officer was shot by a cis man, which the Department of Justice claims was connected to an “Antifa Cell.” It is not known whether the government will attempt to use the defendants’ transness to implicate them in terrorism charges.

And leaked documents indicate that the FBI is compiling a list of groups and individuals involved in extremism based on a number of beliefs including “radical gender ideology.” Their ability to compile such lists may be enhanced by a policy change from the Department of Homeland Security last February that allows the government to surveil people based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.

While some have questioned to what extent the administration intends to actually enforce all of these policies, experts say that the fact they’re being discussed poses a serious risk.

“From 9/11 onward, the United States has been leading a ‘global war on terror,’ so to label somebody as a terrorist is a rallying cry for violence and discrimination,” says Arie Kruglanski, a professor of psychology at the University of Maryland. “This term of terrorism calls people to action. … Once you label somebody as a terrorist, then clearly they present a mortal danger to society, and they need to be fought against.”

‘Tremendously damaging’

Lewis says that being exposed to these attacks can be “tremendously damaging.”

“It’s not even that there are [always] explicitly these immediate legal repercussions that some person will face, but it’s that othering, it’s that sense of fear every day,” he says.

That fear has caused Jewels Jones to withdraw from public life. Jones, a trans man from the South, says that the anti-trans vitriol online after Kirk’s death became too much to handle, and he had to leave social media almost entirely.

“I’m 23, I should be on social media, but I can’t because if I even go onto my timeline, something can trigger me,” Jones told Uncloseted Media. “[I miss] the feeling of freedom.”

With community often hard to find, Jones says he and several other trans people he knows have been struggling with substance use.

“Everyone here has their own reasons for turning to things such as drinking and smoking and partying and just finding [a way] to feel numb or ignore what’s going on,” Jones says. “Just being trans and having to see how everybody views you, how you’re perceived, how you’re feeling, all these different emotions that you feel is more than enough of a reason [to] turn to those things.”

PJ, a trans man from a small town in Arizona, who asked to remain anonymous because he is not out, says that after Trump’s inauguration, he’s started to hide his transness. And he’s not alone: Since the 2024 election, 55 percent of trans people have taken steps to be less visible in their communities.

“It is torture,” PJ says. “I do not like having to lower my voice when I speak to prevent sounding androgynous. I do not like having to hide away my wardrobe for ‘being too gay.’ There is no comfort in overcompensation.”

Individuals aren’t the only ones stepping into the shadows. Kupec has been withdrawing herself and her nonprofit from the internet as much as possible. She says GRACE used to host monthly calls, where as many as 100 people would join to hear from experts on issues facing the trans community. But now, they no longer have public meetings, and internal communications have moved to Signal, an encrypted messaging app.

“We have backed off of doing those things because of the fear of how this could be leveraged against us,” Kupec told Uncloseted Media. “It’s had a chilling effect on our ability to exercise our freedom of speech as individuals and as a nonprofit organization.”

Trying to leave

Because of this fear, many trans Americans are trying to leave. A survey by the Movement Advancement Project found that 43 percent of trans Americans had considered moving to a different state since the 2024 election, with 9 percent having already moved. And the Williams Institute found that 45 percent of trans people wanted to move out of the country.

Kupec has watched noteworthy friends disperse across the globe: Rachel See, the former chair for National Center for Transgender Equality, moved to Portugal; and author and advocate Brynn Tannehill moved to Canada.

“That’s part of what [the administration’s] desired outcome is, to get people to self-deport,” Kupec says.

For many, relocating isn’t easy: For 64 percent of trans people who want to move out of state, cost of living was cited as a barrier. PJ has been trying to move for years. But within the U.S., relatively LGBTQ-friendly states like California and Massachusetts have much higher costs of living, making moving there financially challenging.

Moving internationally is no small feat either — every country has its own laws to navigate around immigration.

PJ says he kept running into barriers while trying to leave. The Netherlands initially seemed promising, but he discovered that the path to residency required him to start a business, which he couldn’t afford to do. Other countries fell through because he didn’t have the money to cover application fees. The closest he got to making it out was when a friend on the east coast of Canada offered to let him stay with them for a while. But it fell through when the friend’s septic tank collapsed, ruining the house and forcing PJ back to the U.S.

“It seems like every plan that you make to try to get out of here, it just gets squashed,” he says.

Those barriers have gotten scarier for PJ as the clock may be ticking for him to be able to leave. In November, the Supreme Court allowed the Trump administration to enforce a ban on passports with gender markers that do not align with an individual’s birth certificate, with the State Department’s website suggesting that passports which have already been updated may be invalidated.

Given all of these threats, PJ believes that trans Americans should be able to seek asylum in other countries. Applications for asylum by trans Americans have been rejected in countries including the Netherlands and Canada, and most European countries don’t view the U.S. as dangerous enough to grant refugee status despite many having issued travel advisories for trans residents visiting the country.

“We can’t really claim asylum right now so there’s not really many other options but sink or swim,” PJ says.

There have been some efforts to push for asylum status for trans Americans. Politicians, advocates and lawyers in Canada and Norway have called for their respective governments to accept trans Americans as refugees. And in July, a Canadian judge blocked the deportation of a nonbinary American who overstayed their visa, with one of the factors considered in the decision being “current conditions for LGBTQ, nonbinary, and transgender persons” in the U.S.

Finding hope and respite

In the face of all this, finding a support network can be crucial to survival. While community has been especially hard to find in the South, Jones says that he’s been able to connect with other transmasc people via reddit communities like r/TMPOC (Trans Masculine People of Color) or r/testosteronekickoff.

Kupec and Brennan find solace through their 12-year relationship. Brennan says, “I love her more now … than I did when I first fell mad smack in love with her.”

“Having love where there’s respect and kindness and joy and excitement and it goes both ways, that is really unique, not a lot of people have that,” she says. “But when you do have it, it’s like, ‘I wanna preserve this and protect this with every ounce of my energy and soul because it’s the center of my life,’ and I know that she feels that way too.”

As Brennan recovers from her heart attack, she’s been watching less news and joined a book club to connect with other people. Kupec, a Catholic, has been putting her faith in God to get through.

“I know who I am, I know my maker knows who I am, and I have strong faith that by doing the right thing, at the end of the day, that’s what’s going to win out.”

Additional reporting by Sam Donndelinger.

-

New York5 days ago

New York5 days agoPride flag raised at Stonewall after National Park Service took it down

-

Opinions5 days ago

Opinions5 days agoUnconventional love: Or, fuck it, let’s choose each other again

-

National4 days ago

National4 days agoFour bisexual women on stereotypes, erasure, representation, and joy

-

Theater4 days ago

Theater4 days agoMagic is happening for Round House’s out stage manager