Miscellaneous

Community in crisis

New Smithsonian AIDS exhibit gathers ‘80s-era artifacts

On June 5, 1981, five unusual cases of pneumonia in patients in Los Angeles were reported in the “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly,” a newsletter from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It was the first notice taken by federal public health officials of a deadly virus — later dubbed HIV, for human immunodeficiency virus — that already claimed countless lives, but without a diagnosis pinpointing why. The plague had begun. It just didn’t have a name yet.

Now, 30 years later, the National Museum of American History, one of the Smithsonian museums on the Mall, the same museum featuring serious history and also pop culture, is marking this anniversary of what became known as the HIV and AIDS epidemic with a three-party display and website beginning June 3.

“With this first official notice of the illness, thousands were infected before anyone knew,” says the exhibit’s curator, Katherine Ott, who has been working with an American History Museum team to plan it for the past year and a half. “The full pattern simply didn’t emerge until later.”

The public health and scientific as well as political responses to HIV/AIDS during the earliest phase, from 1981 to 1987, with original magazine covers and copies of reports plus lab equipment used to isolate the virus, are the focus of one of the three parts, the showcase to be in the museum’s Science in American Life exhibition area.

Another set of materials, dating from 1985 through 2009 — including movie posters, such as for the 1993 film “Philadelphia” starring Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington — will show in the museum’s Archives Center how individuals and society were affected by the epidemic.

Finally, on the first-floor Artifacts Wall, the museum will display a panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt of the Names Project Foundation, honoring Roger Lyon, who died of complications from AIDS in 1984. A year earlier, Lyons testified before a Congressional hearing, throwing down a challenge to his listeners: “I came here today to ask that this nation with all its resources and compassion not let my epitaph read that he died of red tape.”

But red tape and even worse, reluctance to face facts, often rooted in homophobia, led to denial that anything serious was happening and a crucial delay in addressing the epidemic. For years it was ignored by many in the political establishment, such as President Ronald Reagan, whose first speech on the subject only came in 1987.

Looking back at the early period, as the illness emerged and little was done to combat it, Ott, a lesbian, says “I have friends who died, mostly in the 1980s, as a result.”

“There’s a visceral aspect to this that other anniversaries just don’t have, for people who lived through this, including those who became sero-positive in the 1980s and are still alive,” says Ott, who also has “friends and colleagues who are living with AIDS now.”

“Anniversaries like this one are a perfect time to reflect, to see where we are today, and how much things have changed, because it’s almost two generations now since the first HIV reports. But in HIV years it’s probably more like seven generations. So much has changed.”

A month after the first CDC newsletter notice came a short article in the New York Times, headlined “Rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals,” and as the year 1981 ended, 121 deaths were recorded with the cause labeled “gay-related immune deficiency” or GRID.

The Grim Reaper indeed stalked gay men but as the scourge was fully understood, one caused by a virus passed through blood or bodily fluid transmission, its dimensions were finally understood as constituting a global pandemic afflicting both genders, and worst of all in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2009, an estimated 33 million people worldwide were living with HIV-AIDS, with 2.1 million fatalities from the illness that year and also with 2.6 million new infections every year.

Today an estimated 600,000 men, women and children in the U.S. have lost their lives to the many complications from AIDS. Although numbers of those infected had been dropping in the U.S. earlier, that has begun to change in recent years. In 2009, District of Columbia HIV-AIDS officials reported that at least 3 percent of D.C. residents have HIV or AIDS. D.C. is now often called the nation’s HIV-AIDS capital.

Ott, whose Ph.D. is in the history of science and medicine from Temple University, has been a curator at the museum for 15 years. She acknowledges that the exhibit has been extensively vetted within the museum, due to the controversy last year at a sister Smithsonian museum, the National Portrait Gallery, over the “Hide/Seek” exhibit there. She said Brent Glass, the History Museum director, “because of sensitivity over that,” had asked for a review of the HIV-AIDS exhibit by “the Castle,” a reference to the Smithsonian headquarters. Glass now says that, “this display will help visitors understand why these events gripped America 30 years ago.”

Ott says she hopes there’s an audience for the new exhibit, especially for younger people whom she says “have no idea really what we went through, and who now know that HIV infection is not an automatic death sentence, the way it was 25 or 30 years ago.”

She says she has interns today who have never even heard of Rock Hudson, the actor whose death from AIDS-related illness in 1985 made him one of the first celebrities to die from the virus. She sees the exhibit as “a chance for younger people to learn about how there were still sodomy laws in half of the states and how homophobia and the fear of this disease was so intense in the 1980s.”

Of course the virus is not specific to gay male sex, but because it was first detected there, and spread so rapidly through the gay male community, it became linked in the public’s mind to gay males as well as two other marginalized or outsider groups, Haitians and intravenous-drug users. The stigma was deeply set and led to laws being passed that discriminated against people with AIDS in insurance and housing and the workplace.

These sanctions were linked to homophobia and often took the form of enforcing traditional attitudes about sexuality, as cities like San Francisco and New York took steps by 1984 to close down bathhouses and sex clubs. But gay males and their allies, often lesbians, began to act when others would not, to care for those stricken with the illness as well as to push back against vicious anti-gay ignorance with public education campaigns to promote what came to be known as “safe sex.”

The museum exhibit showcases this entire period, with a focus on several of the stages — first, as a public health crisis, when the word was being passed about how AIDS was transmitted and how to prevent the disease’s spread; and then as a scientific mystery, when a high-stakes international race began, to find the cause of the illness; and also as a political flashpoint, when some voices were raised condemning homosexuality as a sin and sometimes even that AIDS was a suitable punishment for such infractions. Other voices challenged Reagan administration inaction, especially in 1987 when activists took to the streets in civil disobedience through ACT UP — the “AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power,” with its familiar pink triangle and its emblematic slogan of “Silence = Death.”

Depicting these stages are magazine covers such as one from The Advocate in 1981, with its front-page headline question, “Is The Urban Gay Male Lifestyle Hazardous to your Health?” about the “new diseases attacking gay men.

Another cover story — headlined “Epidemic,” about the “mysterious and deadly disease called AIDS” — appeared in Newsweek in April 1983. Ott says that its lead author decided to focus on the illness partly as a result of the fact that he had a brother who was gay and who later died from AIDS complications.

Other items on display are the early reports and pamphlets charting the course of efforts to combat the disease. The museum has collected what Ott calls “a lot of the paper ephemera, much of which was educational, to get the word out, including efforts to promote safe-sex practices, such as a booklet titled “How To Have Sex in An Epidemic,” co-authored by Richard Berkowitz and Michael Callen, advocating the use of condoms and other measures for safe sex; and a pamphlet from 1982 titled “Healthy Sex is Great Sex.”

Also shown is an early safe-sex teaching manual, “Teaching AIDS: A Resource Guide on AIDS,” co-authored by a social worker Marcia Quackenbush, whom Ott says “began working in sex education with gay youth in San Francisco and she’s still active.”

Quackenbush in fact will be among the bloggers at the exhibit’s website, which will log in new comments from experts about the exhibit once or twice a month. The exhibit is expected to run until November, though no definite closing has been set yet; it will depend on when the museum’s West Wing, where the materials on display will be housed, must be closed for renovations.

Some of the displayed material comes from the extensive collection of research materials donated in 2008 to the museum by the writer John-Manuel Andriote, author of the 1999 book “Victory Deferred: How AIDS Changed Gay Life in America.” Andriote, who lived in Washington for several decades until returning home to Connecticut in 2007, completed in 2010 a series of interviews to update the book, which will be re-issued later this year in a new edition.

Andriote, who learned he was HIV-positive in 2005, says that in his interviews last year he was, “Startled to hear gay men now say that their sense of the crisis has passed, that HIV has become ‘normal,’ a harsh fact of life but not what defines or necessarily ends it.”

The exhibit also displays antibody tests from 1985 and condoms distributed to gay men in the early and mid-1980s, with a stress on the importance of their use to combat AIDS. One section shows how those test kits emerged from the research in 1983-1984 of two physicians, Luc Montagnier (Pasteur Institute, Paris) and Robert Gallo (National Institute of Health, Bethesda), whose pioneering lab work led to them being recognized as the co-discoverers of HIV as the virus responsible for the cause of AIDS. They co-patented the test kit and split its royalties.

A fascinating feature of the exhibit is the timeline for the years 1981 to 1987, which shows key dates defining the early panic over the illness — such as in 1985, the same year Rock Hudson died and also when the first antibody tests began to be used, when the student Ryan White, a teenaged hemophiliac who contracted HIV from a contaminated blood treatment, was expelled from his Kokomo, Ind., middle school, though doctors insisted he posed no risk to other students.

The next year, as the exhibit shows, came the first drug treatment — AZT, a type of antiretroviral drug, originally marketed under the name Retrovir — that helps to slow the spread of HIV in the body but does not stop it entirely. Also in 1986 came the first official U.S. government policy document on HIV/AIDS, which advocated the use of condoms, infuriating the right wing. It was the landmark study by C. Everett Koop, the U.S. Surgeon General, of which a copy is on display in the exhibit.

But progress in understanding the disease came only in fits and starts, as the exhibit reveals, and key information sometimes lagged for years. Ott notes that for a long period “women with AIDS, who were predominantly poor and African American or Latina, were excluded from clinical tests, and that the official AIDS definition did not include diseases specific to women until 1994.”

The exhibit and its companion website are open to the public beginning today.

Miscellaneous

LA-based TransLatin@ Coalition leads in time of attacks

Members of Congress ‘calling us a radical organization’

As ICE raids intensify across Southern California and anti-immigrant sentiment resurfaces in Orange County, transgender and immigrant communities are once again being targeted. These crackdowns go beyond enforcement — they’re designed to instill fear. At the same time, a coordinated right-wing smear campaign is attempting to discredit the very organizations working to keep these communities safe.

Last month, the TransLatin@ Coalition, a cornerstone in the fight for trans, queer, and immigrant rights in Los Angeles, was publicly named by members of Congress. But this was no recognition. It was a calculated attack.

“They’re calling us a radical organization,” said Bamby Salcedo, president and CEO of the TransLatin@ Coalition. “They’re spreading lies, saying we’re using government funding to abolish ICE and the police and to provide abortion access. We do believe in those things, but the funding we receive is used to serve our people.”

Now, that funding is being stripped away.

In the face of state violence, political backlash, and economic sabotage, TLC is responding the way it always has: by organizing, celebrating, and building a better world. Because when our communities are under attack, we show up — stronger, louder, and more united than ever.

Salcedo, herself a proud trans Latina immigrant, has spent decades fighting for those living at the margins. “I always say I am an intersection walking,” she said with a smile. “Our organization is made up of the people most impacted — and we are the ones leading the work.”

In Los Angeles County, roughly one-third of residents are immigrants, the majority of whom are Latino. Unsurprisingly, trans Latinas represent the largest segment within the local trans community.

Yet even within immigrant justice spaces, trans people are often sidelined.

“It’s a very hetero-centric space,” Salcedo said. “Most of the time, they don’t even consider the lives and experiences of trans and queer immigrants.”

The TransLatin@ Coalition is actively changing that. As a key member of a broad alliance of more than 100 immigrant-serving organizations across Los Angeles, including CHIRLA and the Filipino Workers Center, the TransLatin@ Coalition helped secure over $160 million in American Rescue Plan funds for immigrant housing, internet access, and legal services.

They also co-created the groundbreaking TGIE (Transgender, Gender-Nonconforming, Intersex Empowerment) initiative, which allocates $7 million in Los Angeles County’s annual budget to support trans-led service providers.

“We don’t just want symbolic policies,” said Salcedo. “We fight for resources. We analyze the budget. We make it real.”

Despite these victories, the TransLatin@ Coalition is now confronting devastating federal cuts.

“Our work has been defunded,” Salcedo said bluntly. “Multiple programs are gone. And we’re not alone — trans-led organizations across the country, especially in the South, are facing the same.”

She pointed to a broader backlash against anything associated with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). “The private sector is pulling back. Philanthropy is scared. Even the same corporations that fund us during Pride are investing in our opposition the rest of the year. It’s hypocrisy.”

Rather than retreat, the TransLatin@ Coalition is calling for bold, collective action.

“Now’s the time for people to step up,” said Salcedo. “We have the strategy. We’re doing the work. But we need resources — and we need real solidarity, not just statements.”

To respond to the crisis and raise urgently needed funds, the TransLatin@ Coalition is organizing its Walk for Humanity on Saturday, Aug. 24. The event will begin at 9 a.m. in Silver Lake and march to Sunset and Western, featuring live performances, a resource fair, and a unified call for justice.

And yes — it will be joyful.

“This is a call for all people to stand in solidarity with one another,” said Salcedo. “We want to bring together 1,000 people, each raising $1,000. It’s going to be a beautiful day of community and resistance.”

In a surprise announcement, Salcedo also revealed she will debut her first single — a cumbia track inspired by the movement. “It’s about movement in both senses: our political movement, and moving our bodies,” she laughed. “We can’t let them take away our joy. Joy is how we survive.”

When asked what more local leaders can do, Salcedo didn’t hesitate. “Elected officials are public servants. That means serving all people,” she said. “We may be a small population, but we are deeply impacted — and we contribute so much to this city.”

She pointed to data from LA’s most recent homelessness count, which identified over 2,000 trans and gender-expansive people experiencing homelessness. That number exists thanks in large part to years of advocacy demanding the city count and name trans lives. “We have the data now. There’s no excuse not to invest in our people.”

She also uplifted allies like Los Angeles County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath and newly appointed City Council member Isabel Urado, the first openly LGBTQ person to hold her seat. “They’ve seen our work and are fighting to invest in it,” Salcedo said. “We’re hopeful we’ll see another $10 million in city funding. But we need the community behind us.”

At the end of our conversation, I asked Salcedo what she would say to undocumented, queer, and trans Angelenos who are feeling afraid right now.

Her answer was clear, powerful, and full of love:

“You are a divine creation. You deserve to exist in this world. Walk your path with dignity, love, and respect — for yourself and for others. You belong. You are part of me. You are part of us.”

If standing with trans immigrants, resisting federal rollbacks, and dancing in the streets sounds like your kind of solidarity, join the TransLatin@ Coalition on Aug. 24. Because when we show up together, we protect each other. And when we dance together — we win.

Watch the full interview with Salcedo:

Miscellaneous

LGBTQ cruise ship rescues 11 migrants between Cuba and Mexico

Rescue took place in Yucatán Channel on Wednesday

A cruise ship chartered by an LGBTQ travel company on Wednesday rescued 11 Cubans from a boat that was adrift between their country and Mexico.

Vacaya in a press release said the Royal Caribbean’s Brilliance of the Seas, which had left from New Orleans, discovered the migrants’ boat in the Yucatán Channel, a strait between Mexico and Cuba that connects the Gulf of Mexico (the Trump-Vance administration now refers to the body of water as the Gulf of America) and the Caribbean Sea.

A video that Vacaya provided shows the migrants’ boat before the rescue. Other videos show the rescue taking place.

MTV’s Downtown Julie Brown, who was performing on the ship, described the rescue in a video she posted to social media.

“We are in the middle of a live rescue operation right now,” she said. “The captain of the ship, while we were hauling so fast the other way, thought he saw a boat in distress. So, we looped around … and it was indeed a boat in distress.”

“Nothing speaks more to VACAYA’s values than providing comfort in a moment of need,” said Vacaya CEO Randle Roper in the press release. “I’m so happy we were able to bring these 11 refugees onboard safely and provide medical care, dry clothes, food, and, most importantly, water.”

“It’s sad that some people have to put themselves through such trauma in hopes of finding a better life, but that’s where we are today,” added Roper. “I’m so proud of our LGBT+ guests rallying to collect clothes for these fellow humans in need.”

The ship is scheduled to return to New Orleans on Saturday.

Miscellaneous

The dedicated life and tragic death of gay publisher Troy Masters

‘Always working to bring awareness to causes larger than himself’

Troy Masters was a cheerleader. When my name was called as the Los Angeles Press Club’s Print Journalist of the Year for 2020, Troy leapt out of his seat with a whoop and an almost jazz-hand enthusiasm, thrilled that the mainstream audience attending the Southern California Journalism Awards gala that October night in 2021 recognized the value of the LGBTQ community’s Los Angeles Blade.

That joy has been extinguished. On Wednesday, Dec. 11, after frantic unanswered calls from his sister Tammy late Monday and Tuesday, Troy’s longtime friend and former partner Arturo Jiminez did a wellness check at Troy’s L.A. apartment and found him dead, with his beloved dog Cody quietly alive by his side. The L.A. Coroner determined Troy Masters died by suicide. No note was recovered. He was 63.

Considered smart, charming, committed to LGBTQ people and the LGBTQ press, Troy’s inexplicable suicide shook everyone, even those with whom he sometimes clashed.

Troy’s sister and mother – to whom he was absolutely devoted – are devastated. “We are still trying to navigate our lives without our precious brother/son. I want the world to know that Troy was loved and we always tried to let him know that,” says younger sister Tammy Masters.

Tammy was 16 when she discovered Troy was gay and outed him to their mother. A “busy-body sister,” Tammy picked up the phone at their Tennessee home and heard Troy talking with his college boyfriend. She confronted him and he begged her not to tell.

“Of course, I ran and told Mom,” Tammy says, chuckling during the phone call. “But she – like all mothers – knew it. She knew it from an early age but loved him unconditionally; 1979 was a time [in the Deep South] when this just was not spoken of. But that didn’t stop Mom from being in his corner.”

Mom even marched with Troy in his first Gay Pride Parade in New York City. “Mom said to him, ‘Oh, my! All these handsome men and not one of them has given me a second look! They are too busy checking each other out!” Tammy says, bursting into laughter. “Troy and my mother had that kind of understanding that she would always be there and always have his back!

“As for me,” she continues, “I have lost the brother that I used to fight for in any given situation. And I will continue to honor his cause and lifetime commitment to the rights and freedom for the LGBTQ community!”

Tammy adds: “The outpouring of love has been comforting at this difficult time and we thank all of you!”

No one yet knows why Troy took his life. We may never know. But Troy and I often shared our deeply disturbing bouts with drowning depression. Waves would inexplicitly come upon us, triggered by sadness or an image or a thought we’d let get mangled in our unresolved, inescapable past trauma.

We survived because we shared our pain without judgment or shame. We may have argued – but in this, we trusted each other. We set everything else aside and respectfully, actively listened to the words and the pain within the words.

Listening, Indian philosopher Krishnamurti once said, is an act of love. And we practiced listening. We sought stories that led to laughter. That was the rope ladder out of the dark rabbit hole with its bottomless pit of bullying and endless suffering. Rung by rung, we’d talk and laugh and gripe about our beloved dogs.

I shared my 12 Step mantra when I got clean and sober: I will not drink, use or kill myself one minute at a time. A suicide survivor, I sought help and I urged him to seek help, too, since I was only a loving friend – and sometimes that’s not enough.

(If you need help, please reach out to talk with someone: call or text 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. They also have services in Spanish and for the deaf.)

In 2015, Troy wrote a personal essay for Gay City News about his idyllic childhood in the 1960s with his sister in Nashville, where his stepfather was a prominent musician. The people he met “taught me a lot about having a mission in life.”

During summers, they went to Dothan, Ala., to hang out with his stepfather’s mother, Granny Alabama. But Troy learned about “adult conversation — often filled with derogatory expletives about Blacks and Jews” and felt “my safety there was fragile.”

It was a harsh revelation. “‘Troy is a queer,’ I overheard my stepfather say with energetic disgust to another family member,” Troy wrote. “Even at 13, I understood that my feelings for other boys were supposed to be secret. Now I knew terror. What my stepfather said humiliated me, sending an icy panic through my body that changed my demeanor and ruined my confidence. For the first time in my life, I felt depression and I became painfully shy. Alabama became a place, not of love, not of shelter, not of the magic of family, but of fear.”

At the public pool, “kids would scream, ‘faggot,’ ‘queer,’ ‘chicken,’ ‘homo,’ as they tried to dunk my head under the water. At one point, a big crowd joined in –– including kids I had known all my life –– and I was terrified they were trying to drown me.

“My depression became dangerous and I remember thinking of ways to hurt myself,” Troy wrote.

But Troy Masters — who left home at 17 and graduated from the University of Tennessee at Knoxville — focused on creating a life that prioritized being of service to his own intersectional LGBTQ people. He also practiced compassion and last August, Troy reached out to his dying stepfather. A 45-minute Facetime farewell turned into a lovefest of forgiveness and reconciliation.

Troy discovered his advocacy chops as an ad representative at the daring gay and lesbian activist publication Outweek from 1989 to 1991.

“We had no idea that hiring him would change someone’s life, its trajectory and create a lifelong commitment” to the LGBTQ press, says Outweek’s co-founder and former editor-in-chief Gabriel Rotello, now a TV producer. “He was great – always a pleasure to work with. He had very little drama – and there was a lot of drama at Outweek. It was a tumultuous time and I tended to hire people because of their activism,” including Michelangelo Signorile, Masha Gessen, and Sarah Pettit.

Rotello speculates that because Troy “knew what he was doing” in a difficult profession, he was determined to launch his own publication when Outweek folded. “I’ve always been very happy it happened that way for Troy,” Rotello says. “It was a cool thing.”

Troy and friends launched NYQ, renamed QW, funded by record producer and ACT UP supporter Bill Chafin. QW (QueerWeek) was the first glossy gay and lesbian magazine published in New York City featuring news, culture, and events. It lasted for 18 months until Chafin died of AIDS in 1992 at age 35.

The horrific Second Wave of AIDS was peaking in 1992 but New Yorkers had no gay news source to provide reliable information at the epicenter of the epidemic.

“When my business partner died of AIDS and I had to close shop, I was left hopeless and severely depressed while the epidemic raged around me. I was barely functioning,” Troy told VoyageLA in 2018. “But one day, a friend in Moscow, Masha Gessen, urged me to get off my back and get busy; New York’s LGBT community was suffering an urgent health care crisis, fighting for basic legal rights and against an increase in violence. That, she said, was not nothing and I needed to get back in the game.”

It took Troy about two years to launch the bi-weekly newspaper LGNY (Lesbian and Gay New York) out of his East Village apartment. The newspaper ran from 1994 to 2002 when it was re-launched as Gay City News with Paul Schindler as co-founder and Troy’s editor-in-chief for 20 years.

“We were always in total agreement that the work we were doing was important and that any story we delved into had to be done right,” Schindler wrote in Gay City News.

Though the two “sometimes famously crossed swords,” Troy’s sudden death has special meaning for Schindler. “I will always remember Troy’s sweetness and gentleness. Five days before his death, he texted me birthday wishes with the tag, ‘I hope you get a meaningful spanking today.’ That devilishness stays with me.”

Troy had “very high EI (Emotional Intelligence), Schindler says in a phone call. “He had so much insight into me. It was something he had about a lot of people – what kind of person they were; what they were really saying.”

Troy was also very mischievous. Schindler recounts a time when the two met a very important person in the newspaper business and Troy said something provocative. “I held my breath,” Schindler says. “But it worked. It was an icebreaker. He had the ability to connect quickly.”

The journalistic standard at LGNY and Gay City News was not a question of “objectivity” but fairness. “We’re pro-gay,” Schindler says, quoting Andy Humm. “Our reporting is clear advocacy yet I think we were viewed in New York as an honest broker.”

Schindler thinks Troy’s move to Los Angeles to jump-start his entrepreneurial spirit and reconnect with Arturo, who was already in L.A., was risky. “He was over 50,” Schindler says. “I was surprised and disappointed to lose a colleague – but he was always surprising.”

“In many ways, crossing the continent and starting a print newspaper venture in this digitally obsessed era was a high-wire, counter-intuitive decision,” Troy told VoyageLA. “But I have been relentlessly determined and absolutely confident that my decades of experience make me uniquely positioned to do this.”

Troy launched The Pride L.A. as part of the Mirror Media Group, which publishes the Santa Monica Mirror and other Westside community papers. But on June 12, 2016, the day of the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, Fla., Troy said he found MAGA paraphernalia in a partner’s office. He immediately plotted his exit. On March 10, 2017, Troy and the “internationally respected” Washington Blade announced the launch of the Los Angeles Blade.

In a March 23, 2017 commentary promising a commitment to journalistic excellence, Troy wrote: “We are living in a paradigm shifting moment in real time. You can feel it. Sometimes it’s overwhelming. Sometimes it’s toxic. Sometimes it’s perplexing, even terrifying. On the other hand, sometimes it’s just downright exhilarating. This moment is a profound opportunity to reexamine our roots and jumpstart our passion for full equality.”

Troy tried hard to keep that commitment, including writing a personal essay to illustrate that LGBTQ people are part of the #MeToo movement. In “Ending a Long Silence,” Troy wrote about being raped at 14 or 15 by an Amtrak employee on “The Floridian” traveling from Dothan, Ala., to Nashville.

“What I thought was innocent and flirtatious affection quickly turned sexual and into a full-fledged rape,” Troy wrote. “I panicked as he undressed me, unable to yell out and frozen by fear. I was falling into a deepening shame that was almost like a dissociation, something I found myself doing in moments of childhood stress from that moment on. Occasionally, even now.”

From the personal to the political, Troy Masters tried to inform and inspire LGBTQ people.

Richard Zaldivar, founder and executive director of The Wall Las Memorias Project, enjoyed seeing Troy at President Biden’s Pride party at the White House.

“Just recently he invited us to participate with the LA Blade and other partners to support the LGBTQ forum on Asylum Seekers and Immigrants. He cared about underserved community. He explored LGBTQ who were ignored and forgotten. He wanted to end HIV; help support people living with HIV but most of all, he fought for justice,” Zaldivar says. “I am saddened by his loss. His voice will never be forgotten. We will remember him as an unsung hero. May he rest in peace in the hands of God.”

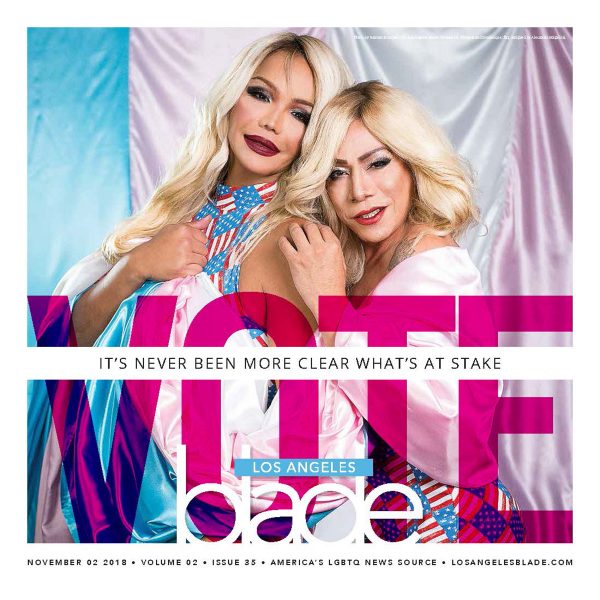

Troy often featured Bamby Salcedo, founder, president/CEO of TransLatina Coalition, and scores of other trans folks. In 2018, Bamby and Maria Roman graced the cover of the Transgender Rock the Vote edition.

“It pains me to know that my dear, beautiful and amazing friend Troy is no longer with us … He always gave me and many people light,” Salcedo says. “I know that we are living in dark times right now and we need to understand that our ancestors and transcestors are the one who are going to walk us through these dark times… See you on the other side, my dear and beautiful sibling in the struggle, Troy Masters.”

“Troy was immensely committed to covering stories from the LGBTQ community. Following his move to Los Angeles from New York, he became dedicated to featuring news from the City of West Hollywood in the Los Angeles Blade and we worked with him for many years,” says Joshua Schare, director of Communications for the City of West Hollywood, who knew Troy for 30 years, starting in 1994 as a college intern at OUT Magazine.

“Like so many of us at the City of West Hollywood and in the region’s LGBTQ community, I will miss him and his day-to-day impact on our community.”

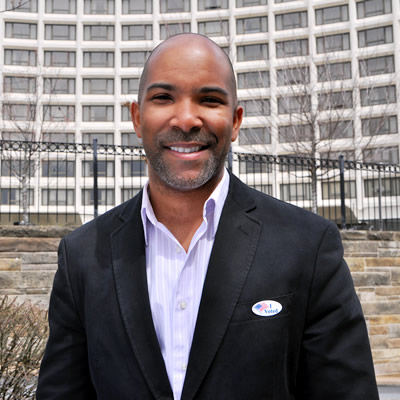

(Photo by Richard Settle for the City of West Hollywood)

“Troy Masters was a visionary, mentor, and advocate; however, the title I most associated with him was friend,” says West Hollywood Mayor John Erickson. “Troy was always a sense of light and working to bring awareness to issues and causes larger than himself. He was an advocate for so many and for me personally, not having him in the world makes it a little less bright. Rest in Power, Troy. We will continue to cause good trouble on your behalf.”

Erickson adjourned the WeHo City Council meeting on Monday in his memory.

Masters launched the Los Angeles Blade with his partners from the Washington Blade, Lynne Brown, Kevin Naff, and Brian Pitts, in 2017.

“Troy’s reputation in New York was well known and respected and we were so excited to start this new venture with him,” says Naff. “His passion and dedication to queer LA will be missed by so many. We will carry on the important work of the Los Angeles Blade — it’s part of his legacy and what he would want.”

AIDS Healthcare Foundation President Michael Weinstein, who collaborated with Troy on many projects, says he was “a champion of many things that are near and dear to our heart,” including “being in the forefront of alerting the community to the dangers of Mpox.”

“All of who he was creates a void that we all must try to fill,” Weinstein says. “His death by suicide reminds us that despite the many gains we have made, we’re not all right a lot of the time. The wounds that LGBT people have experienced throughout our lives are yet to be healed even as we face the political storm clouds ahead that will place even greater burdens on our psyches.”

May the memory and legacy of Troy Masters be a blessing.

Veteran LGBTQ journalist Karen Ocamb served as the news editor and reporter for the Los Angeles Blade.

-

Federal Government4 days ago

Federal Government4 days agoTwo very different views of the State of the Union

-

Virginia4 days ago

Virginia4 days agoVa. activists preparing campaign in support of repealing marriage amendment

-

Opinions4 days ago

Opinions4 days agoThe global cost of Trump’s foreign aid ideology

-

Opinions3 days ago

Opinions3 days agoCriteria for supporting a candidate in D.C.