Arts & Entertainment

Sam inspires college athletes to come out

Despite progress, homophobia persists in locker rooms

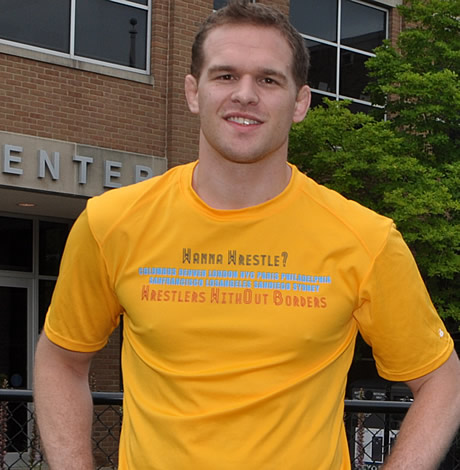

Hudson Taylor, founder of Athlete Ally, said Michael Sam has inspired many collegiate athletes to come out. (Washington Blade photo by Michael Key)

A number of collegiate athletes have come out as gay in the months since former University of Missouri defensive end Michael Sam publicly declared his sexual orientation.

Parker Camp, a member of the University of Virginia swim team, began coming out to his family and friends earlier this year as he told Outsports.com, an LGBT sports website. He and four other teammates held a handwritten sign that read “2 of us gay. The other 3 don’t care” as part of an ad campaign promoting diversity.

Derrick Gordon of the University of Massachusetts in April became the first member of a NCAA Division 1 basketball team to come out as gay. Connor Mertens, a kicker for the Willamette University football team in Oregon, in June publicly acknowledged his bisexuality.

Edward “Chip” Sarafin, a backup senior offensive lineman for Arizona State University, earlier this month told Compete, a Phoenix-based sports magazine, that he began coming out to his teammates last year.

“It was really personal to me, and it benefited my peace of mind greatly,” he told Compete.

Hudson Taylor, founder of Athlete Ally, a group that advocates for LGBT athletes, told the Washington Blade during a recent telephone interview he feels Sam has inspired many collegiate athletes.

“[He] has walked in the shoes of every closeted athlete and every closeted athlete is walking in Michael Sam’s shoes,” he said. “As Michael has a successful career and has come out without incident, I think it shows that next generation of athletes that sport is a welcoming environment for them to be themselves.”

Helen Carroll, director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights Sports Project, agreed.

“They can see positive things happening with those people,” said Carroll. “That can even be just a college student coming out, their coming out story and their teammates accept them and their coach is accepting.”

Challenges remain for collegiate athletes who are considering coming out.

Carroll said homophobic comments in the locker room persist and may deter collegiate athletes from publicly disclosing their sexual orientation or gender identity and expression. She also referred to what she described as “old-school coaches” who discourage their players from coming out until they graduate.

“There’s still that out there in a lot of places,” Carroll told the Blade.

The case of former Penn State women’s basketball coach Rene Portland remains among the most high-profile examples of anti-LGBT discrimination in collegiate sports.

A former player, Jennifer Harris, accused Portland in a 2005 lawsuit of having a “no-lesbian” policy and trying to force her to quit the team, even though she is not gay.

Harris also sued then-Penn State Athletics Director Tim Curley, who is among the former university administrators facing charges for allegedly covering up sex-abuse allegations against former assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky.

She reached a confidential settlement with Portland and Curley in 2007.

Penn State later fined Portland $10,000 and ordered her to take a diversity-sensitivity class after the university settled with Harris.

Portland resigned in 2007 after 27 seasons.

“We’re not as likely to see a case like that, but I am sure somewhere across the nation there are more Rene Portland’s out there,” said Carroll.

Other cases have generated headlines over the past year.

Anthony Villarreal, a former track runner at William Jessup University, a Christian university outside of Sacramento, Calif., said school administrators expelled him last year because he is gay. Leah Johnson last month told Outsports.com an assistant coach at the University of Richmond in Virginia told her to break up with her girlfriend, Miah Register, “before she steps foot on this campus” to play for the team.

In spite of these cases and others like them, Carroll and Taylor maintain more collegiate athletes will come out. And they both look to the way the University of Missouri handled Sam’s decision to publicly disclose his sexual orientation as an example of how they feel administrators and coaches should handle it.

“Michael Sam was out for a good period of time before the world knew about it,” Taylor told the Blade. “It seemed like it didn’t matter one bit to his teammates, to his coaches or to the Missouri family. Missouri did a great job and really showed that they are a welcoming environment for LGBT athletes.”

Movies

Radical reframing highlights the ‘Wuthering’ highs and lows of a classic

Emerald Fennell’s cinematic vision elicits strong reactions

If you’re a fan of “Wuthering Heights” — Emily Brontë’s oft-filmed 1847 novel about a doomed romance on the Yorkshire moors — it’s a given you’re going to have opinions about any new adaptation that comes along, but in the case of filmmaker Emerald Fennell’s new cinematic vision of this venerable classic, they’re probably going to be strong ones.

It’s nothing new, really. Brontë’s book has elicited controversy since its first publication, when it sparked outrage among Victorian readers over its tragic tale of thwarted lovers locked into an obsessive quest for revenge against each other, and has continued to shock generations of readers with its depictions of emotional cruelty and violent abuse, its dysfunctional relationships, and its grim portrait of a deeply-embedded class structure which perpetuates misery at every level of the social hierarchy.

It’s no wonder, then, that Fennell’s adaptation — a true “fangirl” appreciation project distinguished by the radical sensibilities which the third-time director brings to the mix — has become a flash point for social commentators whose main exposure to the tale has been flavored by decades of watered-down, romanticized “reinventions,” almost all of which omit large portions of the novel to selectively shape what’s left into a period tearjerker about star-crossed love, often distancing themselves from the raw emotional core of the story by adhering to generic tropes of “gothic romance” and rarely doing justice to the complexity of its characters — or, for that matter, its author’s deeper intentions.

Fennell’s version doesn’t exactly break that pattern; she, too, elides much of the novel’s sprawling plot to focus on the twisted entanglement between Catherine Earnshaw (Margot Robbie), daughter of the now-impoverished master of the titular estate (Martin Clunes), and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi), a lowborn child of unknown background origin that has been “adopted” by her father as a servant in the household. Both subjected to the whims of the elder Earnshaw’s violent temper, they form a bond of mutual support in childhood which evolves, as they come of age, into something more; yet regardless of her feelings for him, Cathy — whose future status and security are at risk — chooses to marry Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif), the financially secure new owner of a neighboring estate. Heathcliff, devastated by her betrayal, leaves for parts unknown, only to return a few years later with a mysteriously-obtained fortune. Imposing himself into Cathy’s comfortable-but-joyless matrimony, he rekindles their now-forbidden passion and they become entwined in a torrid affair — even as he openly courts Linton’s naive ward Isabella (Alison Oliver) and plots to destroy the entire household from within. One might almost say that these two are the poster couple for the phrase “it’s complicated.” and it’s probably needless to say things don’t go well for anybody involved.

While there is more than enough material in “Wuthering Heights” that might easily be labeled as “problematic” in our contemporary judgments — like the fact that it’s a love story between two childhood friends, essentially raised as siblings, which becomes codependent and poisons every other relationship in their lives — the controversy over Fennell’s version has coalesced less around the content than her casting choices. When the project was announced, she drew criticism over the decision to cast Robbie (who also produced the film) opposite the younger Elordi. In the end, the casting works — though the age gap might be mildly distracting for some, both actors deliver superb performances, and the chemistry they exude soon renders it irrelevant.

Another controversy, however, is less easily dispelled. Though we never learn his true ethnic background, Brontë’s original text describes Heathcliff as having the appearance of “a dark-skinned gipsy” with “black fire” in his eyes; the character has typically been played by distinctly “Anglo” men, and consequently, many modern observers have expressed disappointment (and in some cases, full-blown outrage) over Fennel’s choice to use Elordi instead of putting an actor of color for the part, especially given the contemporary filter which she clearly chose for her interpretation for the novel.

In fact, it’s that modernized perspective — a view of history informed by social criticism, economic politics, feminist insight, and a sexual candor that would have shocked the prim Victorian readers of Brontë’s novel — that turns Fennell’s visually striking adaptation into more than just a comfortably romanticized period costume drama. From her very opening scene — a public hanging in the village where the death throes of the dangling body elicit lurid glee from the eagerly-gathered crowd — she makes it oppressively clear that the 18th-century was not a pleasant time to live; the brutality of the era is a primal force in her vision of the story, from the harrowing abuse that forges its lovers’ codependent bond, to the rigidly maintained class structure that compels even those in the higher echelons — especially women — into a kind of slavery to the system, to the inequities that fuel disloyalty among the vulnerable simply to preserve their own tenuous place in the hierarchy. It’s a battle for survival, if not of the fittest then of the most ruthless.

At the same time, she applies a distinctly 21st-century attitude of “sex-positivity” to evoke the appeal of carnality, not just for its own sake but as a taste of freedom; she even uses it to reframe Heathcliff’s cruel torment of Isabella by implying a consensual dom/sub relationship between them, offering a fragment of agency to a character typically relegated to the role of victim. Most crucially, of course, it permits Fennell to openly depict the sexuality of Cathy and Heathcliff as an experience of transgressive joy — albeit a tormented one — made perhaps even more irresistible (for them and for us) by the sense of rebellion that comes along with it.

Finally, while this “Wuthering Heights” may not have been the one to finally allow Heathcliff’s ambiguous racial identity to come to the forefront, Fennell does employ some “color-blind” casting — Latif is mixed-race (white and Pakistani) and Hong Chau, understated but profound in the crucial role of Nelly, Cathy’s longtime “paid companion,” is of Vietnamese descent — to illuminate the added pressures of being an “other” in a world weighted in favor of sameness.

Does all this contemporary hindsight into the fabric of Brontë’s epic novel make for a quintessential “Wuthering Heights?” Even allowing that such a thing were possible, probably not. While it presents a stylishly crafted and thrillingly cinematic take on this complex classic, richly enhanced by a superb and adventurous cast, it’s not likely to satisfy anyone looking for a faithful rendition, nor does it reveal a new angle from which the “romance” at its center looks anything other than toxic — indeed, it almost fetishizes the dysfunction. Even without the thorny debate around Heathcliff’s racial identity, there’s plenty here to prompt purists and revisionists alike to find fault with Fennell’s approach.

Yet for those looking for a new window into to this perennial classic, and who are comfortable with the radical flourish for which Fennell is already known, it’s an engrossing and intellectually stimulating exploration of this iconic story in a way that exchanges comfortable familiarity for unpredictable chaos — and for cinema fans, that’s more than enough reason to give “Wuthering Heights” a chance.

Crimsyn and Tatianna hosted the new weekly drag show Clash at Trade (1410 14th Street, N.W.) on Feb. 14, 2026. Performers included Aave, Crimsyn, Desiree Dik, and Tatianna.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

Theater

Magic is happening for Round House’s out stage manager

Carrie Edick talks long hours, intricacies of ‘Nothing Up My Sleeve’

‘Nothing Up My Sleeve’

Through March 15

Round House Theatre

4545 East-West Highway

Bethesda, Md. 20814

Tickets start at $50

Roundhousetheatre.org

Magic is happening for out stage manager Carrie Edick.

Working on Round House Theatre’s production of “Nothing Up My Sleeve,” Edick quickly learned the ways of magicians, their tricks, and all about the code of honor among those who are privy to their secrets.

The trick-filled, one-man show starring master illusionist Dendy and staged by celebrated director Aaron Posner, is part exciting magic act and part deeply personal journey. The new work promises “captivating storytelling, audience interaction, jaw-dropping tricks, and mind-bending surprises.”

Early in rehearsals, there was talk of signing a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) for production assistants. It didn’t happen, and it wasn’t necessary, explains Edick, 26. “By not having an NDA, Dendy shows a lot of trust in us, and that makes me want to keep the secrets even more.

“Magic is Dendy’s livelihood. He’s sharing a lot and trusting a lot; in return we do the best we can to support him and a large part of that includes keeping his secrets.”

As a production assistant (think assistant stage manager), Edick strives to make things move as smoothly as possible. While she acknowledges perfection is impossible and theater is about storytelling, her pursuit of exactness involves countless checklists and triple checks, again and again. Six day weeks and long hours are common. Stage managers are the first to arrive and last to leave.

This season has been a lot about learning, adds Edick. With “The Inheritance” at Round House (a 22-week long contract), she learned how to do a show in rep which meant changing from Part One to Part Two very quickly; “In Clay” at Signature Theatre introduced her to pottery; and now with “Nothing Up My Sleeve,” she’s undergoing a crash course in magic.

She compares her career to a never-ending education: “Stage managers possess a broad skillset and that makes us that much more malleable and ready to attack the next project. With some productions it hurts my heart a little bit to let it go, but usually I’m ready for something new.”

For Edick, theater is community. (Growing up in Maryland, she was a shy kid whose parents signed her up for theater classes.) Now that community is the DMV theater scene and she considers Round House her artistic home. It’s where she works in different capacities, and it’s the venue in which she and actor/playwright Olivia Luzquinos chose to be married in 2024.

Edick came out in middle school around the time of her bat mitzvah. It’s also around the same time she began stage managing. Throughout high school she was the resident stage manager for student productions, and also successfully participated in county and statewide stage management competitions which led to a scholarship at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) where she focused on technical theater studies.

Edick has always been clear about what she wants. At an early age she mapped out a theater trajectory. Her first professional gig was “Tuesdays with Morrie” at Theatre J in 2021. She’s worked consistently ever since.

Stage managing pays the bills but her resume also includes directing and intimacy choreography (a creative and technical process for creating physical and emotional intimacy on stage). She names Pulitzer Prize winning lesbian playwright Paula Vogel among her favorite artists, and places intimacy choreographing Vogel’s “How I learned to Drive” high on the artistic bucket list.

“To me that play is heightened art that has to do with a lot of triggering content that can be made very beautiful while being built to make you feel uncomfortable; it’s what I love about theater.”

For now, “Nothing Up My Sleeve” keeps Edick more than busy: “For one magic trick, we have to set up 100 needles.”

Ultimately, she says “For stage managers, the show should stay the same each night. What changes are audiences and the energy they bring.”

-

Baltimore3 days ago

Baltimore3 days ago‘Heated Rivalry’ fandom exposes LGBTQ divide in Baltimore

-

Real Estate3 days ago

Real Estate3 days agoHome is where the heart is

-

District of Columbia3 days ago

District of Columbia3 days agoDeon Jones speaks about D.C. Department of Corrections bias lawsuit settlement

-

European Union3 days ago

European Union3 days agoEuropean Parliament resolution backs ‘full recognition of trans women as women’