Commentary

Living an ‘American nightmare’

Blade contributor describes La. detention facility as hell

Editor’s note: Yariel Valdés González is a Washington Blade contributor who has asked for asylum in the U.S.

Valdés has previously described the conditions at the Bossier Parish Medium Security Facility in Plain Dealing, La., where he remains in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody as a human rights violation. An ICE spokesperson in response to Valdés’ previous allegations said the agency “is committed to upholding an immigration detention system that prioritizes the health, safety, and welfare of all of those in our care in custody, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) individuals.”

The Blade received Valdés’ op-ed on June 29.

PLAIN DEALING, La. — The American dream to live in absolute freedom; safe from the threats, persecution, violence, psychological torture and even death the Cuban dictatorship has imposed on me because of my journalistic work fell apart in my hands as soon as I arrived in Louisiana. The Cubans here who are also seeking protection from the U.S. government welcomed me to the Bossier Parish Medium Security Facility with an ironic surprise. They opened their arms and told me, “Welcome to hell!”

I could hardly believe they have spent nine, 10 and even 11 months asking, waiting for a positive response from immigration authorities in their cases.

I was under the illusion that after an asylum official who interviewed me at the Tallahatchie County Correctional Center in Tutwiler, Miss., on March 28 determined I had a “credible fear of persecution or torture” in Cuba, one hearing with an immigration judge would be enough to obtain my conditional release and pursue my case in freedom as U.S. law allows. But I was wrong. The locals (here at Bossier) once again took it upon themselves to dash my hopes.

“Nobody comes out of Louisiana!” they proclaimed.

It only took a few minutes for my dream, like that of many others, to turn into a nightmare. The more than 30 migrants who arrived in Louisiana on the afternoon of May 3, coming from Mississippi after more than a month detained at Tallahatchie, were plunged into a deep depression that continues today. Only the tears under the blanket that nobody can see are able to ease my desperation for a few minutes and then I once again feel it in my chest when I think of my family in Cuba who continues to receive threats of jail and death from the Cuban dictatorship because of my work with “media outlets of the enemy.” This reality is the only thing that awaits me back there. I therefore see the situation in Louisiana and I am once again afraid. I cannot see an exit. Prisoner here, prisoner if I return to Cuba. I feel trapped.

Violation of their own laws

I realized a few days after I arrived in Louisiana the subjectivity of who makes the decisions matters, not objectivity or attachment to those who are being held. Louisiana feels like a lost piece of “gringo” geography at which nobody seems to look, or to the contrary, it is a coldly calculated strategy that triumphs on authoritarianism, abuse of power or intransigence. I don’t know what to think.

More than a few who have arrived here have come to the conclusion the U.S. has made migrants its new business. Keeping migrants in their custody for so long keeps hundreds of employees and lawyers in business, as well as generating huge profits for the prisons with which U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement contracts. It has become clear the government prefers to waste more than $60 a day per migrant than set us free under our own recognizance.

“Louisiana is an anti-immigrant state,” Arnaldo Hernández Cobas, a 55-year-old Cuban man whose asylum process has taken 11 months, tells me. “It is not possible for any of the thousands of people who go through the process to leave victorious.”

Hernández tells me ICE agents have not met with him once during his confinement and the deportation officer has never seen him.

“I don’t know if I am allowed to have bail,” he says. “Judge Grady A. Crooks affirms that we do not qualify for this and he does not give it to those who qualify for it because they can flee. This only happens in this state because migrants in other places are released and can pursue their cases on the outside after they make bail.”

Another way to obtain conditional freedom is through parole, a benefit the federal government offers to asylum petitioners who enter the country legally and are found to have a credible fear of suffering, facing persecution or being tortured in their countries of origin.

“To grant it, ICE asks for a series of questions that relatives should send to them, but what is happening is that they don’t give them enough time to do so,” says Arnaldo.

This is exactly what happened with me.

My family managed to send the documents the next day for my parole interview, which was scheduled for the following day. ICE nevertheless denied me parole because I did not prove “that I am not a danger to society.” I am sure they didn’t even take my case seriously.

There are stories that border on the absurd because many migrants have received their parole hearing notifications the same day they should have filed their documents. One therefore feels as though ICE mocks you to your face and your feelings of helplessness reach the max.

The awarding of parole is a new procedure ICE must complete, but it does not go beyond that. They use this and other crafty strategies to “stay good” in the eyes of the law and they therefore keep asylum seekers in custody for months. They bring them to hearings they will not win, pushing for the deportation of those who do not succumb to the pressure of confinement without properly assessing the risk to their lives that returning to their native countries would entail.

ICE is required to free us a few days after it grants parole, and we already know it doesn’t want to do this. Their goal is to keep us locked up at all costs.

“The cruel irony is that the majority of asylum seekers who follow the law and present themselves at official ports of entry don’t have to ask an immigration judge for their release from custody,” declared Laura Rivera, a lawyer for the Southern Poverty Law Center, an organization that provides legal assistance to immigrants, in an article titled, “Stuck in ‘hell’: Cuban asylum seekers wither away in Louisiana immigration prisons.” “To the contrary, their only avenue to secure their freedom is to ask the same agency that detains them, the Department of Homeland Security.”

But DHS — as Rivera details in the article published by the Southern Poverty Law Center — is ignoring its mandate to consider requests for release in detail. And to the contrary it denies conditional release without justification.

“Men are kept hidden from the outside world, locked up and punished for defending their rights and are forced to bring their cases before immigration judges who deny them with rates of up to 100 percent,” affirmed Rivera.

Another of the process violations in Arnaldo’s case was he was assured where he was first detained that he could win his case along with that of his wife, “but when he came” to Louisiana the judge “told me this was not allowed, that each case is different.” Arnaldo’s life cannot be different from that of his wife because they have been together for 37 years. His wife has been free for nine months, but he remains behind bars. And so, it happens with mothers and sons, brothers and people who have identical cases. Once again, subjectivity determines a person’s fate.

During his hearing with Crooks, Arnaldo declared he feels “very uncomfortable” because he considers him an extremist.

“He said that he only recognizes extreme cases,” says Arnaldo. “Doors mean nothing to him. He describes himself as a deportation judge, not an asylum judge. In the entire time that I have been here nobody has won asylum, not even bail, only deportations.”

Conclusive proof of the judge’s extremism came one day when another judge ran the hearings and the migrants who presented their cases that morning received asylum. The example could not have been more illustrative.

Douglas Puche Moxeno, a 23-year-old Venezuelan man who has spent nine months in Louisiana, also said the detainees “did not receive more information on how the process should be followed and how one should do it.”

“I don’t know if they explained to us the ways to obtain a conditional release,” he says.

In relation to their hearings, Douglas says “the judge told me that he knew the real situation in Venezuela, but he did not grant me asylum because I am not an extreme case. He is waiting for someone to come to the United States without an arm or a leg to be accepted.”

The migrants in Louisiana are trying every way possible to be released. They have made these complaints on television stations and have even gone to Cuban American U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.).

“We have reached the point of filing a lawsuit against ICE,” Douglas explains. “A team of lawyers from the Southern Poverty Law Center have proposed a lawsuit seeking a reconsideration of parole. This is one of the most hopeful ways that we have to obtain freedom. If we are successful, the benefits will be for everyone.”

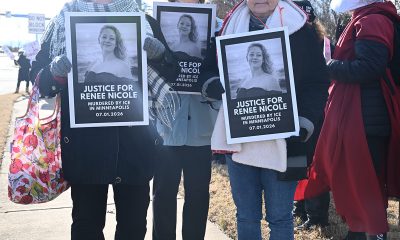

“Various protests to pressure authorities and to reclaim our rights as immigrants have been organized,” says Douglas. “Relatives, lawyers and various institutions have come together in Miami, Washington and even here in Louisiana to make ICE aware of the injustices that have been committed against us for more than a year.”

‘This is not your country’

Bossier is a jail deep in Louisiana, hidden in the woods that surround it. Each day inside of it is a constant struggle for survival that takes a huge toll on my physical, psychological and above all emotional capacities. More than 300 migrants live in four dorms in cramped conditions with intense cold and zero privacy.

My stay here reminds me of the school dorms in Cuba where we were forced to share smells, tastes and basic needs. Here we also share Hindu, African, Chinese, Nepali, Syrian and Central American migrants’ beliefs, cultures and ways of life.

My personal space is reduced to a narrow metal bed that is bolted to the floor, a drawer for my things and a thin mattress that barely manages to keep my spine separated from the metal, which sometimes causes back pain. The most painful thing, however, is the way the officers treat us. For “better or for worse,” you feel as though you are a federal prisoner.

“According to ICE, we are ‘detainees,’ not prisoners, but we have still suffered physical and psychological abuses,” says Arnaldo. “I remember one time when an official dragged a Salvadoran man to the hole for three days simply for eating in his bed. They don’t offer anything to us and they don’t talk to us, they yell. They wake you up by kicking the bed.”

“The slightest pretext is used to disconnect the microwave, the television or deny us ice, affirming this is a luxury and not a necessity,” alleges Arnaldo. “When we complain about these situations. They tell us, ‘This is not your country.'”

Smiles are not common inside the dorm. The faces of affliction and sadness predominate. Good news is almost always false and the frustration and stress this confinement causes us therefore returns.

“I feel very sad, afflicted here, as though I had killed someone because of the mistreatment that we receive, the place’s conditions,” declares Damián Álvarez Arteaga, a 31-year-old man who has spent 11 months as a prisoner in the U.S.

“Freedom is the most precious thing a human being has,” he adds. “I hope that I will receive a positive response to my case after spending so much time detained. We have demonstrated to the U.S. that we are truly afraid of suffering persecution or torture in Cuba.”

Hours in here seem to have no end: They stretch, they multiply, but they never shorten or pass quickly. Our only contact with the outside the world are telephone communications or video calls (at elevated prices) with relatives, friends or lawyers and sporadic trips to the patio to greet the son and take fresh air.

“In all of the time that I have been here, I have seen the son a few times and only for 15 minutes and this is because we have complained,” recalls Arnaldo.

The yard, as we also call it, is a small rectangle of fences and surveillance cameras with a cement surface at the center of it where some of us play soccer when they give us a ball. I roll the pants of my yellow uniform up to my knees to allow the sun to warm my extremities a bit while my eyes wander towards the lush forest that is a few meters away from me. I admire the sky, the few vehicles that are driving on the nearby highway and I take deep breaths of oxygen because I know I had just come out of the deep sea and desperately needed air to keep me alive.

“Everyday is the same here from the same food to the same activities,” says Douglas. “This prison does not have sufficient spaces to accommodate so many people for so long. We don’t have a library or family visits.”

‘Soup is currency’

My day at Bossier begins a bit before 5 a.m. With the call to “line-up,” I receive a plastic tray with my breakfast. Today is cereal day, low-fat milk, bread and a small portion of jelly. The menu is the same each day of the week. I always save part of it because there is nothing more to eat until midday.

“The food is not correct,” opines Damián. “My stomach is already used to that small portion. A piece of bread with hot sauce and some vegetables or mortadella cannot sustain an adult man, nor can it keep you in shape to resist such a stressful process.”

The last meal of the day is at 4 p.m., and because of this it is a fantasy to be in bed at 11 p.m. with a full stomach. I reduce the hunger pains with an instant soup to which I add some carrots and a hot dog that I steel for myself from the day’s meals.

Since I still have some money, I can buy soups and extra things to make Bossier’s bad food a little better. Bossier classifies those who don’t receive economic support from their families as “indigent” and they are forced to clean up for their fellow detainees in exchange for a Maruchan soup. Here soup is currency. Everything begins and ends with it, the savior of hungry nights.

“You can buy these and other things at elevated prices in the commissary, the only store to which we have access and for which we depend on everything,” says Damián.

Bossier’s medical services on the other hand are so basic that there is not even a doctor or nurse on call, nor is there an observation room for patients and consultations only take place from Monday to Friday.

“One who gets sick is put in punishment cells, isolated and alone, which psychologically affects us,” notes Arnaldo. “People sometimes don’t say they don’t feel well because they are afraid they will be sent to the ‘well.’ In extreme cases they bring you to a hospital with your feet, hands and waist shackled and they keep you tied to the bed, still under guard. I prefer to suffer before being hospitalized like that.”

Yuni Pérez López, a 33-year-old Cuban, experienced this unfortunate situation first hand. He was on the hole for six days because he had a fever.

“I felt as though I was being punished for being sick,” he says. “And even when the doctor discharged me, they kept me there. It was like being in an icebox: Four walls, a bed, a toilet and a light that never turns off. To leave from there I had to stop eating for an entire day to get the officials’ attention and they returned me to the dormitory.”

Bossier also leaves you chilled to the bone because we cannot use blankets or sheets to cover ourselves from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. It is not a question of esthetic or discipline because the officials are not interested in whether your bed is made well. The only thing that bothers them is when we are cover ourselves from the dorm’s intense cold.

The migrants interviewed by the Washington Blade are those who have been at Bossier the longest. They are all appealing Crooks’ decision not to grant them political asylum. I have not presented my case yet, so I am still a little hopeful that I will receive the protection of the U.S. Like them, I am trying to get used to this harsh reality and be strong, although most of the time sadness consumes me and erases positive thoughts.

The U.S. to me — like for many — does not represent a comfortable life, the newest car or McDonald’s. None of this will ever be able to fill the void of my family, friends or passionate love that I left behind. The U.S. represents the opportunity to LIVE, so I will hold on to it until the end.

I recently lost my dog, Argo.

He was a pit bull, big, sweet, endlessly cuddly, and for 15 years he was my constant. The kind of presence you stop consciously noticing until they’re gone and the quiet hits you all at once. Pit bulls have a reputation. Argo never got the memo. He just loved people, completely and without condition, from the moment he met them until his last day.

I wasn’t prepared for what happened next.

My phone filled up. Instagram lit up. Texts came in from people I hadn’t heard from in months, in some cases years. Hugs from neighbors. Messages from colleagues. Condolences from people I’d lost touch with, some through nothing more than the slow drift of busy lives in a busy city, and some honestly through small tiffs and misunderstandings that neither of us ever bothered to resolve.

And sitting with all of that love pouring in, I found myself asking a question I wasn’t expecting: Why has it taken this long?

We do this in D.C. We get caught in our heads, our calendars, our ambitions. We let weeks turn into months. We let a small misunderstanding calcify into distance because nobody wants to be the first one to reach out, nobody wants to seem like they need something. We perform resilience so well that sometimes the people who care about us most don’t know we need them.

And then something breaks open, a loss, a moment of real vulnerability, and suddenly people show up. And you realize the connection was always there. It just needed permission.

Argo gave people permission. Even in dying, he did what he always did when he was alive. He brought people together.

I’ll be honest with you about where I’ve been lately. As I’ve climbed the entrepreneurial ladder, something quietly shifted. People stopped seeing Gerard. They started seeing a title, a resource, someone who could give them something or who owed them something. A character. Not a person. And when most of your day is spent inside other people’s problems and crises, you can start to feel it, a slow creep of cynicism that you don’t even notice until one day you realize you’ve gone numb.

And I’m not alone in that. Look around. We just watched innocent people die while those in power looked us in the face and called it something else. We watched people erupt over a 10-minute halftime performance like it was the greatest threat to our country. Everywhere you look there is something designed to make you angry, or exhausted, or both. Anger and numbness have become survival strategies. I understand it. I’ve lived it.

But here is what Argo reminded me.

The world is not what the loudest voices say it is. The world is what shows up when something real happens. And what showed up for me, after losing my sweet boy, was people. Caring, loving, present people who put down whatever they were doing to reach out to a friend. Some of them I hadn’t spoken to in too long. Some of them I’d had friction with. All of them showed up anyway.

That is the world. That is what it actually is underneath all the noise.

I think we’ve forgotten that. Or maybe we haven’t forgotten it, maybe we’re just so tired and overstimulated and battle-worn that we’ve stopped letting ourselves feel it. Because feeling it requires vulnerability, and vulnerability feels dangerous right now. It’s easier to scroll. It’s easier to stay mad. It’s easier to keep a wall up and call it wisdom.

Argo spent 15 years showing me a different way. He never met a stranger. He never held a grudge. He never saved his love for people who deserved it on paper. He just gave it, freely, every single time. Not a reward. Not a transaction. Just the most natural thing in the world.

Grief burns off everything that isn’t essential and leaves only what matters. What’s left for me is this: the world is full of good people. You may be surrounded by more of them than you know. And if you’ve gone numb, or angry, or so busy surviving that you’ve stopped connecting, I want you to know that the feeling can come back. It came back for me.

Reach out to someone today. Close a distance you’ve let grow. Tell someone they matter. Not because everything is perfect, but because connection is how we survive when it isn’t. Living disconnected, mad and closed off isn’t living at all. It’s a slower kind of dying.

Death came to teach me how to live. I hope this saves you some time.

Gerard Burley, also known as Coach G, is founder and CEO of Sweat DC.

Commentary

Defunding LGBTQ groups is a warning sign for democracy

Global movement since January 2025 has lost more than $125 million in funding

In over 60 countries, same-sex relations are criminal. In many more, LGBTIQ people are discriminated against, harassed, or even persecuted. Yet, in most parts of the world, if you are an LGBTIQ person, there is an organization quietly working to keep people like you safe: a lawyer fighting an arrest, a shelter offering refuge from violence, a hotline answering a midnight call. Many of those organizations have now lost so much funding that they may be forced to close.

One year ago this week, the U.S. government froze foreign assistance to organizations working on human rights, democracy, and development worldwide. The effects were immediate. For LGBTIQ communities, the impact has been severe and far-reaching.

For 35 years, Outright International has helped build and sustain the global movement for the rights of LGBTIQ people, working with local partners in more than 75 countries. Many of those partners are now facing sudden closure.

Since January 2025, more than $125 million has been stripped from efforts advancing the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer people globally. That figure represents at least 30 percent of yearly international funding for this work. Organizations that ran emergency shelters, legal defense programs, and HIV prevention services have been forced to close or drastically scale back operations. At Outright alone, we lost funding for 120 grants across nearly 50 countries. We estimate that, without intervention, 20 to 25 percent of our grantee partners risk shutting down entirely.

But this is not only a story about one community. It is a story about how authoritarianism works, and what it costs when we fail to recognize the pattern.

The playbook is not subtle

Researchers at Outright and partners across human rights and democracy movements have documented the same sequence playing out across sectors worldwide: governments defund organizations before passing restrictive legislation, eliminating the groups most likely to document abuses before abuses occur.

In December, CIVICUS downgraded its assessment of U.S. civic freedoms from “narrowed” to “obstructed,” citing what it called a “rapid authoritarian shift.” The message was unmistakable: independent organizations that hold power to account are under growing pressure, in the United States and around the world.

And the effects have cascaded globally. When one of the world’s largest funders of democracy support and human rights work withdraws, it doesn’t just leave a funding gap. It sends a signal to authoritarians everywhere: the coast is clear.

The timing is not coincidental. In the super election year of 2024, 85 percent of countries with national elections featured anti-LGBTIQ rhetoric in campaigns. Across the 15 countries we tracked, governments proposed or enacted laws restricting gender-affirming care, rolling back legal gender recognition, and censoring LGBTIQ expression. The defunding often came first. Governments know that if they can starve the movement, there will be no one left to document what comes next.

Why US readers should care

It may be tempting to see this as a distant crisis, especially at a moment when LGBTIQ rights in the United States are under real pressure. But this story is closer to home than it appears. American funding decisions often help determine whether organizations protecting LGBTIQ people abroad can keep their doors open. And when independent organizations are weakened, no matter where they are, the consequences do not stay contained. The same political networks driving anti-LGBTIQ legislation in the United States share strategies and resources with movements abroad. Global repression and domestic rollback are not separate stories. They are the same story, unfolding in different places.

LGBTIQ organizations are often the first target, but never the last

Why target LGBTIQ communities first? Because we are politically easier to isolate. The same playbook — foreign funding restrictions, bureaucratic harassment, banking access denial — is now being deployed against environmental groups, independent media, women’s rights organizations, and election monitors. When one part of our community is silenced, all of us become more vulnerable. What happens to us is a preview of what happens to everyone.

This is not speculation. It is documented history. In Hungary, the government restricted foreign funding for civil society before passing its “anti-LGBTQ propaganda” law. In Russia, “foreign agent” designations preceded the criminalization of LGBTIQ identity. In Uganda, funding restrictions on human rights organizations came before the Anti-Homosexuality Act. The pattern repeats because it works.

And yet, even as these attacks intensify, victories continue. In 2025, Saint Lucia struck down a colonial-era law criminalizing consensual same-sex intimacy after a decade of regional planning and coalition-building. Courts in India, Japan, and Hong Kong upheld trans people’s rights. Budapest Pride became the largest in Hungarian history — and one of the country’s biggest public demonstrations — despite a government ban. In Thailand, years of patient advocacy culminated in marriage equality becoming law in 2025, the first such victory in Southeast Asia.

These wins happened because our movement built the capacity to survive hostility. Legal defense funds. Documented evidence. Regional coalitions. Emergency response networks. The organizations behind these victories are precisely the ones now facing drastic funding cuts and even closure.

What we are doing and what we need

On Jan. 20, 2026, Outright International publicly launched Funding Our Freedom, a $10 million emergency campaign running through June 30, 2026. We have already secured over $5 million in pledges from more than 150 donors. But the gap remains enormous.

The campaign supports two priorities that must move together. Half of the funds go directly to frontline LGBTIQ organizations facing sudden shortfalls: keeping staff paid, maintaining safe spaces, securing legal support, and continuing essential services. The other half supports Outright’s global work: documenting abuses, training activists, and advocating for LGBTIQ inclusion at the United Nations and other international forums. This is how LGBTIQ people remain seen, heard, and defended, even when governments attempt to erase them.

We structured Funding Our Freedom this way because frontline support without protection is fragile, and global advocacy without frontline truth is hollow. Both must survive.

Funding Our Freedom is not charity. It is how we keep the global LGBTIQ movement alive when governments try to erase it.

A call to those who believe in equality and democracy

If you are part of the LGBTIQ community, this moment is personal. Whether you give, share this work, host a small fundraiser, or bring others into the effort, you become part of what keeps our global community connected and protected.

If you are an ally or simply someone who believes in fairness, free expression, and accountable government, this fight is yours too. The defunding of LGBTIQ organizations is not an isolated decision. It is a test case. If it succeeds, the same tactics will be used against every group that challenges power and defends vulnerable people.

We are not asking for sympathy. We are asking for commitment. The organizations now being forced to close are the ones that document abuses, provide legal defense, support people in crisis, and show up when no one else will. If they disappear, we lose more than services. We lose the ability to know what is happening and to respond.

Authoritarians understand this. That is why they target us first.

The question is whether the rest of us understand it in time.

Maria Sjödin is the executive director of Outright International, where they has worked for over two decades advocating for LGBTIQ human rights worldwide. Learn more at outrightinternational.org/funding-our-freedom.

January arrives with optimism. New year energy. Fresh possibilities. A belief that this could finally be the year things change. And every January, I watch people respond to that optimism the same way. By adding.

More workouts. More structure. More goals. More commitments. More pressure to transform. We add healthier meals. We add more family time. We add more career focus. We add more boundaries. We add more growth. Somewhere along the way, transformation becomes a list instead of a direction.

But what no one talks about enough is this: You can only receive what you actually have space for. You don’t have unlimited energy. You have 100 percent. That’s it. Not 120. Not 200. Not grind harder and magically find more.

Your body knows this even if your calendar ignores it. Your nervous system knows it even if your ambition doesn’t want to admit it. When you try to pour more into a cup that’s already full, something spills. Usually it’s your peace. Or your consistency. Or your health.

What I’ve learned over time is that most people don’t need more motivation. They need clarity. Not more goals, but priority. Not more opportunity, but discernment.

So this January, instead of asking what you’re going to add, I want to offer something different. What if this year becomes a season of no.

No to things that drain you. No to things that distract you. No to things that look good on paper but don’t feel right in your body. And to make this real, here’s how you actually do it.

Identify your one true priority and protect it

Most people struggle with saying no because they haven’t clearly said yes to anything first. When everything matters, nothing actually does. Pick one priority for this season. Not 10. One. Once you identify it, everything else gets filtered through that lens. Does this support my priority, or does it compete with it?

Earlier this year, I had two leases in my hands. One for Shaw and one for National Landing in Virginia. From the outside, the move felt obvious. Growth is celebrated. Expansion is rewarded. More locations look like success. But my gut and my nervous system told me I couldn’t do both.

Saying no felt like failure at first. It felt like I was slowing down when I was supposed to be speeding up. But what I was really doing was choosing alignment over optics.

I knew what I was capable of thriving in. I knew my limits. I knew my personal life mattered. My boyfriend mattered. My family mattered. My physical health mattered. My mental health mattered. Looking back now, saying no was one of the best decisions I could have made for myself and for my team.

If something feels forced, rushed, or misaligned, trust that signal. If it’s meant for you, it will come back when the timing is right.

Look inside before you look outside

So many of us are chasing who we think we’re supposed to be— who the city needs us to be. Who social media rewards. Who our resume says we should become next. But clarity doesn’t come from noise. It comes from stillness. Moments of silence. Moments of gratitude. Moments where your nervous system can settle. Your body already knows who you are long before your ego tries to upgrade you.

One of the most powerful phrases I ever practiced was simple: You are enough.

I said it for years before I believed it. And when I finally did, everything shifted. I stopped chasing growth just to prove something. I stopped adding just to feel worthy. I could maintain. I could breathe. I could be OK where I was.

Gerard from Baltimore was enough. Anything else I added became extra.

Turning 40 made this clearer than ever. My twenties were about finding myself. My thirties were about proving myself. My forties are about being myself.

I wish I knew then what I know now. I hope the 20 year olds catch it early. I hope the 30 year olds don’t wait as long as I did.

Because the only way to truly say yes to yourself is by saying no first.

Remove more than you add

Before you write your resolutions, try this. If you plan to add three things this year, identify six things you’re willing to remove. Habits. Distractions. Commitments. Energy leaks.

Maybe growth doesn’t look like expansion for you this year. Maybe it looks like focus. Maybe it looks like honoring your limits. January isn’t asking you to become superhuman. It’s asking you to become intentional. And sometimes the most powerful word you can say for your future is no.

With love always, Coach G.

Gerard Burley, also known as Coach G, is founder and CEO of Sweat DC.