a&e features

SPORTS ISSUE 2019: Trans women face many hurdles in quest to compete fairly

Testosterone levels, hormones, evolving policies, anti-trans bias among complicating factors

LGBT issues have never been easy — marriage, military service, AIDS, you name it, no gain came without a fight. But if, as is commonly posited, trans rights lag a good 10 or more years behind gay and lesbian advances, perhaps the thorniest issue of all is fair competition for trans women and their cis women opponents, in both recreational and elite sport.

Imagine that women’s sports had never become “a thing” and all adults competed against each other. In figure skating, for example, only three women have landed quad jumps in competition, yet no male singles skater today can be remotely competitive without multiple quads in his arsenal (Nathan Chen landed six at the 2018 Olympics yet failed to medal).

Yes, Billie Jean King (a lesbian) famously beat Bobby Riggs in the 1973 “Battle of the Sexes” in tennis, but she was 29 and he was 55. What would happen if Michael Phelps and Katie Ledecky (swimming) or Novak Djokovic and Serena Williams (tennis) were to face off in the pool or on the court?

Perhaps more realistically, what would happen if Chen, Phelps or Djokovic came out as trans, opted out of hormone replacement therapy and competed as women? Some LGBT advocates say even suggesting such a scenario is transphobic or, at best, displays a gross misunderstanding of the issue. But it’s a question being asked by many.

The International Olympic Committee changed its policy in early 2016 to allow trans women to compete provided they demonstrate their testosterone level has been below a certain level for at least one year prior to their first competition. It supplants the previous 2003 policy that required both gender reassignment surgery and two years of hormone therapy (trans men are allowed to compete without restriction).

Chris Mosier, a trans male athlete and creator of transathlete.com, a resource site for trans sports advocacy at all levels, says the debate has been unfair and overheated.

“We’ve had several Olympic games since the policy has been in place for trans athletes,” says the 38-year-old Mosier, who in 2015 became the first openly trans man to make a Men’s U.S. National Team when he qualified for the Spring Duathlon team. “We’re talking something like 50,000 Olympians have passed through and not a single trans athlete or single trans woman has participated. The fears people have and the stereotypes and misconceptions they’re putting out there about trans women dominating sports just simply haven’t happened.”

That’s also the argument of trans activist/author Brynn Tannehill whose book “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Trans” came out in 2018. She points out that there has not been a single trans athlete dominator since the Olympic policy change or since the NCAA changed its policy to allow trans people to compete sans surgery in 2011. She claims a year of testosterone removal is “sufficient to remove competitive advantage.”

But some cis athletes have balked at getting beaten by trans women competitors. And they’re not just complaining — some are taking legal action. Elsewhere, governing bodies in various sports at all levels are either facing or have faced challenges in how to keep their eligibility policies current and trans-inclusive. That collides with the widely held trans argument that what a trans person has done or not done by way of hormone replacement therapy or gender reassignment surgery is a personal matter that doesn’t make them more or less a woman or man than those at other stages of transition.

Others say trans bias is something impossible to ignore or downplay because it’s so rampant.

“There will always be people who will say a trans female athlete is cheating when she wins or when she doesn’t win, say, ‘She just didn’t try hard enough,’” says gay sports filmmaker David McFarland (“Alone in the Game”). “People are looking for a reason to discriminate against trans people in sport, that’s a given.”

Connecticut controversy

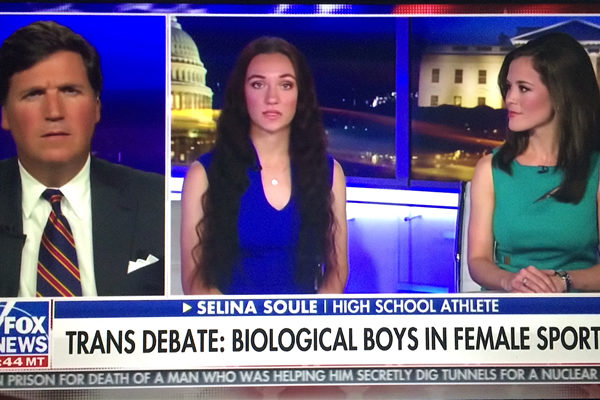

Selina Soule, a 16-year-old runner at Glastonbury High School in Glastonbury, Conn., is frustrated. She says she’s suffered because trans competitors in her conference — Terry Miller of Bloomfield High and Andraya Yearwood of Cromwell High — have been allowed to compete no questions asked against she and her fellow cis women runners.

Miller won the State Open 200-meter title for the second straight year in 2019 and won the Class S titles in the 100 and 200, as well as the New England 200-meter championship. Yearwood, who is also transgender, finished third in the 100 meters in Class S and fourth in the 100 in the State Open.

Subsequently Soule wasn’t able to compete in the New England regional Championships where she would have been seen by college scouts. Miller and Yearwood have won 15 women’s state championships since the Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference (CFAC) changed its policy to allow them to compete as women. Conference leaders say they’re simply following state law.

“The CIAC is committed to providing transgender student athletes with equal opportunities to participate in CIAC athletic programs consistent with their gender identity,” its guidebook reads. Connecticut is one of 19 states that has similar laws.

“I am very happy for these athletes and I fully support them for being true to themselves and having the courage to do what they believe in,” Soule said in a Fox News interview. “But in athletics, it’s an entirely different situation. It’s scientifically proven that males are built to be physically stronger than females. It’s unfair to put someone who is biologically a male who has not undergone anything in terms of hormone therapy against cisgender girls.”

Miller and Yearwood have declined to state publicly what, if any, hormone therapy or testosterone suppression — more on that later — they have undergone.

Soule told the Wall Street Journal the experience has been demoralizing.

“It’s just really frustrating and heartbreaking because we all train extremely hard to shave off just fractions of a second off of our time and these athletes can do half the amount of work that we do and it doesn’t matter,” she said. “We have no chance of winning.”

“It’s definitely a complicated issue,” Soule’s mother Bianca, told the Blade in a brief phone interview. “You have to compete based on the physical abilities you were born with, if you want to call it that. That’s why we separate the two genders. If there were no differences, there would never have been a women’s sports. Unfortunately our trans girls are caught in the middle. The rule is the problem. I tried to contact our Connecticut association to try to look into it, even meet with one of the trans girls’ fathers to try to understand and come up with a solution but we were met with only shut doors. The frustrating part has been the refusal of the athletic bodies to even consider and listen to our side of it.”

Yearwood and Miller issued statements through the ACLU. “I will continue to fight for all trans people to compete and participate consistent with (whom) we are,” Miller wrote. “There is a long history of excluding black girls from sport and policing our bodies. I am a runner and I will keep running and keep fighting for my existence, my community and my rights.”

“I will never stop running,” Yearwood wrote. “I hope that the next generation of trans youth doesn’t have to fight the fights that I have. I hope they can be celebrated when they succeed, not demonized.”

“It is heartbreaking to see yet another attack on trans youth for simply participating in activities alongside their peers,” Chase Strangio, ACLU staff attorney added. “Discrimination on the basis of sex extends to trans people. Girls who are transgender are girls.”

A legal group called Alliance Defending Freedom (it calls itself a “conservative Christian nonprofit”) filed a complaint in June with the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights on behalf of Soule and two of her teammates claiming they have “been negatively impacted by the policy.”

“One of these male athletes now holds 10 records inside the state of Connecticut that were once held by 10 individual girls established over the course of about a 20-year period so it’s fundamentally unfair to allow biological males to step into women’s sports and frankly dominate them and take away opportunities not just to medal, but to be on the podium and advance to the next level of competition and even compete for scholarships for young women like Selena,” Christiana Holcomb, an Alliance Defending Freedom attorney, told Tucker Carlson on Fox News.

“It’s grotesque and insane and it hurts women and girls,” Carlson said on the broadcast.

The issue is especially acute among high school athletes because students are often just figuring out whom they are, how they identify and are less likely to have time logged living fully transitioned lives.

Dawn Stacey Ennis, managing editor of OutSports and a trans woman, says the trans-girls-bumping-cis-girls-off-the-medal-stand argument is misleading because college coaches recruiting look at time, not placement.

“They don’t care who placed first, second or third — all colleges look at and what every coach has told me is that the time is what matters because time is immutable, you can’t change that. It doesn’t matter if you ran against a trans person or not,” Ennis says.

She also says Soule and her representatives aren’t being totally forthcoming.

“I talked to her mother and watched the video and when she said (Selina) didn’t get to qualify for the event in Boston, she sort of fibbed a little bit. She didn’t qualify in that event, but she did qualify in another event. But, of course, that’s not a good headline. It’s much better to say, ‘I didn’t get to go because of these girls.’ … They have to make the trans girls out to be the boogyemen because somebody else has to be responsible for her losing. It has to be someone else’s fault, but that’s not what sports is about.”

Tennis legend Martina Navratilova, a lesbian, was heavily criticized for a Sunday Times op-ed she wrote in February arguing trans women should not be allowed to compete against cis women.

“It’s insane and it’s cheating,” she wrote. “I am happy to address a transgender woman in whatever form she prefers, but I would not be happy to compete against her. It would not be fair. … To put the argument at its most basic: a man can decide to be female, take hormones if required by whatever sporting organization is concerned, win everything in sight and perhaps earn a small fortune, and then reverse his decision and go back to making babies if he so desires,” she wrote.

She was heavily criticized for her comments, removed from the advisory board of Athlete Ally (an LGBT athlete advocacy group) and called out by trans activists such as cyclist Rachel McKinnon (the first trans woman to win a world track cycling title in Oct., 2018), who called Navratilova’s concern a “wild fantasy worry that is an irrational fear of something that doesn’t happen … transphobia.”

Navratilova wrote of being frustrated with “what seems to be a growing tendency among transgender activists to denounce anyone who argues against them and to label them all as transphobes.”

She backpedaled somewhat, apologizing for using the word “cheating,” but called for a debate on the issue based “not on feeling or emotion but science,” BBC News reported.

How are other sports organizing bodies handling the issue?

Western states solution

One group that’s done about as well as anyone it appears is the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run whose board members this year adopted a trans-inclusive policy that accepts “a runner’s self-declared gender at registration … at face value,” the New York Times reports.

“If, however, a finisher in the top 10 or among the top three in their age group is challenged, race management may ask the runner for documentation that they have undergone medically supervised hormone treatment for gender transition for at least a year before the race,” the Times reports.

The issue arose last December when Grace Fisher, a trans runner who favors ultradistance competition, was selected through the race’s traditional lottery system for the 100-mile ultramarathon that takes place in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California every June.

If a trans runner is challenged and it’s upheld by race management, their placement may be bumped but they would be allowed to keep their finisher’s buckle. It ended up not being an issue for Fisher (she came in 20th) but she says she appreciates the care organizers put into their policy.

“They were so concerned about me and wanted to ensure my safety,” says the 38-year-old Hancock, Md., resident, a federal employee with United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. “They went out of their way to welcome me and wish me good luck. … It was quite amazing, but I don’t think the other runners really picked up on it. They just saw me as another female.”

Fisher acknowledges the issue is dicier on the high school level.

“I think we do need more research, but there are so few of us, it’s hard to get more,” she says. “I think personally, and this may not be popular in the trans community, but yeah, the high school situation needs to be looked at more. That’s such a tricky situation because one, they’re teenagers so their hormones are raging whether they’re cis or if they’ve started to transition, they may still have an advantage. I just haven’t seen any science on it so I’m hesitant to state any opinion at this point.”

There’s a bounty of information on the topic available from all kinds of sources, from thorough, balanced studies in popular magazines such as Men’s Health’s March piece “The Truth About Trans Athletes;” to folksy, readable blogs such as “On Transgender Athletes and Performance Advantages” earlier this year at sportsscientists.com; to scholarly research in medical journals such as “Sport and Transgender People: a Systematic Review of the Literature Relating to Sport Participation and Competitive Sport Policies,” published online two years ago on the National Institute of Health website, which studied eight other articles and reviewed 31 sport policies.

The findings were — perhaps surprisingly for some — more trans validating than one might expect.

“In relation to sport-related physical activity, this review found the lack of inclusive and comfortable environments to be the primary barrier to participation for transgender people.” Also, the “lack of inclusive and comfortable environments (is) the primary barrier to participation for transgender people. … transgender people had a mostly negative experience in competitive sports because of the restrictions of the sport’s policy placed on them.”

Researchers also found “no direct or consistent research suggesting transgender female individuals (or male individuals) have an athletic advantage at any stage of their transition (e.g. cross-sex hormones, gender-confirming surgery) and therefore competitive sport policies that place restrictions on transgender people need to be considered and potentially revised.”

The ‘T’ word

A central — but not total — factor in this discussion is testosterone levels.

The hormone, an androgen is produced in both men and women, but not nearly as much in cis women. It affects the body in many ways.

In men, high levels of testosterone are made in the testes. The adrenal glands make much lower levels above the kidneys. Women produce testosterone in both their adrenal glands and ovaries, but testes in men produced much higher rates: in men, it’s 295 to 1,150 nanograms of testosterone per deciliter of blood while the levels in women are usually in the range of 12-61 nanograms per deciliter of blood, according to the New York Times and other medical sites consulted.

Testosterone also builds both skeletal and cardiac muscle and increases the number of red blood cells. The effects are present whether they’re there naturally or introduced. The effects are amplified further among elite athletes and make a huge difference in performance. Male champions in sports across the board are always faster and stronger than records set by women, although it’s not as simple as it may appear at first: researchers have found it has more of an effect in middle-distance races; it could have been less of a factor for Fischer in the Western States 100.

But the connection between testosterone and athletic performance isn’t always an exact science. When researchers measured the T levels of elite athletes from 15 Olympic sports, more than 25 percent of the men were below the level (10 nanomoles per liter) required of trans Olympic women, according to a study from “Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology” cited in the aforementioned Men’s Health article. Nearly 7 percent had less than 5 nmol/L and there was significant overlap between male and female athletes. Cis male powerlifters had surprisingly low T levels while cis male track and field athletes were higher.

Further complicating matters is the fact that some cis women rarely but occasionally possess unusually high T levels. Caster Semenya, 28, an elite runner and Olympic champion from South Africa, for instance, has been banned from some races. In May, the Court of Arbitration for Sport in Switzerland ruled that women with unusually high T levels (far above the ranges normally seen) cannot compete against other women in some races unless they take drugs to suppress their levels, the New York Times reported.

Men also tend to be on average about 6 inches taller than women. The average U.S. adult male weighs 195 pounds vs. 168 pounds for women. A study from the Applied Physiology journal found that men had an average of 26 pounds more skeletal muscle mass than women and about 40 percent more upper-body and 33 percent more lower-body strength on average.

Fairness factor

So what does fair look like?

Mosier chuckles when asked to ponder the issue with sexism, patriarchy and anti-trans bias taken out of the equation.

“I don’t know what that would look like and I wish I could predict the future,” he says. “But sport is inherently about advantage and that makes people uncomfortable. There are certain advantages a very tall basketball player has. We don’t ask him to chop off a few inches of their height to make a more level playing field. Some people burn lactic acid faster than their competitors. At the 2016 Olympics in Rio, Katie Ledecky, beat her competition by a full pool length but she’s thought of as a once-in-a-lifetime, exceptional athlete but her advantage may be that she is never questioned, but there really needs to be more studies done on what the impact is over time before anyone could start to talk about unfair advantage.”

Not disqualifying certain individuals with extraordinary physical gifts is also commonly used as a rationale for why trans women shouldn’t be punished for physical attributes beyond their control.

“What are they supposed to do, tell these people they can’t compete because their arms are too big or their torsos are too long,” Ennis says. “That’s not fair either. Trans girls may have physical gifts but I would hope those would be advantages that would make cis girls try harder. I don’t think it’s unfair because there are always going to be people who are better than you.”

McFarland agrees.

“It’s an affront to every athlete to be penalized for one’s intrinsic biology,” he says. “Do we tell a really strong female shot putter or discus thrower she’s too strong to compete? Do we have a height cut-off in the NBA? Where would it end?”

But by that argument, why are women’s divisions needed in any sport?

Ennis says no women — cis or trans — want to compete against men. Asking the question, she says, implies skeptics don’t see trans women as true women.

“This idea that some guy’s gonna go put on a wig and a skirt, go dominate the sports world, then go back and start fathering babies, that’s just not what the trans experience is about,” Ennis says.

Mosier says any advantage trans women in theory may have, is negated by the social stigma they endure.

“It has a huge impact on their training and performance,” Mosier says. “People aren’t transitioning to gain a competitive advantage. What they encounter would never offset a gold medal or world championship. They just want to compete. … The footage of some of these track meets and what’s said to the competitors and their parents, its’ really toxic and vile and horrific in so many ways that a young person would have to deal with that lack of understanding.”

(Photo by Zhen Heinemann; courtesy Mosier)

And while some argue that anyone who’s been through a male puberty will on average retain a physical advantage — testosterone doesn’t vastly impact one’s height or reach — Fisher says even that argument is suspect.

“It’s like having a Mustang with a small engine,” Fisher says. “You still have this big car but it just doesn’t have the engine. We lost a lot of muscle mass, probably more than a fit female, but also a lot more bone mass. The muscle-to-mass ratio is lower,” she says. “I don’t really know if trans women have any advantage. I think it’s questionable.”

As one would expect, there’s huge support for trans athletes — both men and women — among LGBT advocacy groups. But the story changes significantly when you loop other stakeholders into the discussion.

Fallon Fox was the first openly trans athlete in MMA history in a 2012-2014 career that included just a single loss. She encountered substantial transphobia in her groundbreaking career but also questions about the fairness of her bouts. During a 2014 fight against Tamikka Brents, Brents suffered a concussion, orbital bone fracture and required seven staples to her head after the first round, which ended the fight. Brents, a lesbian, said after the fight it wasn’t a fair match.

Brents declined a Blade interview request saying she’d put the issue behind her but said at the time that Fox was far stronger than any other women she’d ever fought in a long MMA career.

Fox dismissed the advantage claim in a guest editorial on an MMA news website saying, “I’m a transgender woman. I deserve equal treatment and respect to other types of women. I feel this is so ridiculously unnecessary and horribly mean spirited.”

Elusive consensus

While it’s understandable that consensus eludes the sports world among the Alliance Defending Freedom, Fox News and the like, it’s still thorny because there’s no consensus either among trans people.

Some believe trans athletes should be able to compete without any medical intervention at all, others believe in a physical barometer to gauge trans eligibility while others say there should be a separate league for trans athletes, not a widely held view because of their small numbers. They mostly agree, however, that participation is essential.

Ennis of OutSports says the fact that trans women haven’t emerged as a dominant force in elite sports and even in high school sports don’t win constantly helps support the general push toward trans inclusion.

“If a study were to come out and say conclusively that trans women are physically unbeatable by cisgender women and every cis woman lost every time, I would throw in my hat and say, ‘That’s it, we can’t do it.’ But the facts aren’t in. Cis women do beat trans women. Not every single time, but there’s not one sport in which trans women totally dominate. These two (Connecticut) high school girls are winning competitions, but they don’t win every single one they’re in.”

“No trans person is trying to participate for personal gain,” McFarland says. “They just want to do it in a healthy manner. This idea that people are transitioning just to dominate is something that critics continually get wrong and this ungrounded fear of trans people, that they’ll come in and take over, that’s really the dictionary definition of transphobia. … The current science and data reveals it’s a nonsense argument.”

a&e features

Meet D.C.’s Most Eligible Queer Singles

Our annual report, just in time for Valentine’s Day

Just in time for Valentine’s Day, the Blade is happy to present our annual Most Eligible Singles issue. The Singles were chosen by you, our readers, in an online nominations process.

John Marsh

Age: 35

Occupation: DJ and Drag Entertainer

How do you identify? Male

What are you looking for in a mate? I’m looking for someone who’s ready to dive into life’s adventures with me. someone independent and building their own successes, but equally open to supporting each other’s dreams along the way. I know that probably sounds simple because, honestly, who isn’t looking for that? But my life and career keep me very social and busy, so it’s important to me to build trust with someone who understands that. I want a partner who knows that even when life gets hectic or I’m getting a lot of attention through my work in the community, it doesn’t take away from my desire to build something real, intentional, and meaningful with the right person.

Biggest turn off: My biggest turnoff is arrogance or judgment toward others. I’m most drawn to people who are comfortable being themselves and who treat everyone with the same level of respect and care. I’ve worked hard for the success I’ve found, but I believe in staying humble and leading with kindness, and I’m attracted to people who live the same way. I’m also turned off by exclusionary mindsets, especially the idea that sapphic folks don’t belong in gay spaces. Our community is vibrant, diverse, and strongest when it’s shared with everyone who shows up with respect and love

Biggest turn on: I’m drawn to people who can confidently walk into new spaces and create connection. Being able to read a room and make others feel comfortable shows emotional intelligence and empathy, which I find incredibly attractive. I also come from a very social, open, and welcoming family environment, so being with someone who embraces community and enjoys bringing people together is really important to me.

Hobbies: I have a lot of hobbies and love staying creative and curious. I’m a great cook, so you’ll never have to worry about going hungry around me. In my downtime, I watch a lot of anime and I will absolutely talk your ear off about my favorites if you let me. I’m also a huge music fan and K-pop lover (listen to XG!), and I’m a musician who plays the cello. I spend a lot of time sewing as well, which is a big part of my creative expression. My hobbies can be a little all over the place, but I just genuinely love learning new skills and trying new things whenever I can.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? This year feels like a huge milestone for me. I’m getting ready to join a tour this summer and want to represent myself well while building meaningful connections in every city I perform in. I’m also focused on growing as a DJ, sharing more mixes and content online, and reaching a big creative goal of releasing original music that I’m producing.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I have a lovely Akita named Grady that I’ve had for 10 years and always want pets in my life. I’m open to kids when/if the time is right with the right person.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? Hell no. I don’t see political differences as just policy disagreements anymore – they often reflect deeper values about how we treat people and support our communities. I’m very progressive in my beliefs, and I’m looking for a partner who shares that mindset. For me, alignment in values like equity, compassion, and social responsibility is non-negotiable in a relationship. To be very clear about my beliefs, I’m outspoken about my opposition to immigration enforcement systems like ICE and believe both political parties have contributed to policies that have caused real harm to vulnerable communities. I’m also deeply disturbed by the ongoing violence in Palestine and believe we need to seriously examine our support of military actions that have resulted in the loss of countless innocent lives. These aren’t abstract political opinions for me, they are moral issues that directly inform who I am and what I stand for.

Celebrity crush: Cocona

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I used to own a catering business in college that paid for my school — I also went to a Christian college, lol.

Jackie Zais

Age: 35

Occupation: Senior director at nonprofit

How do you identify? Lesbian woman

What are you looking for in a mate? Looking for someone who’s curious about the world and the people in it — the kind of person who’s down to explore a new spot one night and stay in with takeout the next. Confident in who they are, social without being exhausting, adventurous but grounded, thoughtful but not pretentious. Someone who can be funny while still taking life (and relationships) seriously.

Biggest turn off: Doesn’t have strong opinions. I love hearing a wild hot take.

Biggest turn on: When someone can make me belly laugh.

Hobbies: Number one will always be yapping with friends over food, but I also love collecting new hobbies. Currently, I crochet (and have some dapper sweater vests as a result), listen to audiobooks on what I personally think is a normal speed (2x) and play soccer and pickleball. But I’ve tried embroidery, papier-mâché, collaging, collecting plants, scrap booking, and mosaic.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? I’ve recently started swimming and I want to look less like a flailing fish and more like someone who knows what they’re doing.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I have neither but open to kids

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? My best friend is a moderate Democrat and that’s as far right as I’m willing to go.

Celebrity crush: Tobin Heath

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I’m the daughter of Little Miss North Quincy 1967.

Kevin Schultz

Age: 39

Occupation: Product manager

How do you identify? Gay

What are you looking for in a mate? You know 2001’s hottest Janet Jackson single, “Someone to Call My Lover?” To quote Janet, “Maybe, we’ll meet at a bar, He’ll drive a funky car; Maybe, we’ll meet at a club, And fall so deeply in love.”

Realistically though, I’d love to find someone who loves to walk everywhere and who avoids the club because it’s too loud and crowded. Later in the song, our songstress opines “My, my, looking for a guy, guy, I don’t want him too shy; But he’s gotta have the qualities, That I like in a man: Strong, smart, affectionate” and I’m quite aligned there – I’m an introvert looking for someone more extroverted.

I’m looking for someone who is different from me. When the math works, one plus one should equal two. Two becoming one is more art, and my relational approach is more science, or, I guess, math.

Biggest turn off: I’m turned off by a lot of superficially small things — chewing with one’s mouth open, dirty or untrimmed fingernails, oh, and also, lack of self awareness. My personal brand of anxiety is hyper self-aware, so I’m very turned off by someone who doesn’t realize that they exist in the world with others.

Biggest turn on: Competency. Or maybe…eyes? So perhaps, you see my conundrum — I’m very engaged by people who are deeply engaged by something, but I’d be lying if I said a sharp gaze and a wink didn’t get me. And, you know, some stamina in all avenues, mental and physical doesn’t hurt either.

Hobbies: Fixing everyone’s WiFi (this did actually get me a date once), and just generally fixing everyone’s everything. If it’s got a plug, screen, or buttons I can probably help you with it. On my own, I’m really into smart home devices and automation, and just to be timely, my latest thing is setting up and tuning my own instance of OpenClaw. (No one should actually do this, which is why I’m trying.) Together, we could also explore such hobbies as visiting every Metro station, visiting and exploring a new airport, and exploring why there are so many gay transit nerds. There’s no non-fake sounding way to say this but I also just love knowledge seeking, so I’d also love to go on an adventure with you where we learn something brand new.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? My biggest goal is to arrive to 2027 just a little better than I arrived to 2026. A few gym goals, a few personal goals, a few work goals; I hope to get a few of them across the finish line. At the risk of holding myself accountable, one of those goals is to be able to flawlessly side plank for over a minute. Please don’t mistake me for a huge gym rat; I just have a questionable relationship with balance and I’m really working on it.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I’ll just be blunt: no pets. Stating this on my Hinge profile resulted in an exponential loss of matches, so it’s very fun to trot out the idea. Primarily, I’m allergic to cats and dogs so my aversion is mostly biological. I’m not, however, allergic to kids — big fan of my various nieces and nephews — but I’d really only consider kids of my own if my chosen companion and I could financially afford them without compromise, and at this age I’ve become opinionated about the life I want to live.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? No. This becomes a simpler answer with each passing day, unfortunately.

Celebrity crush: If I’m being of the moment, of course, it’s going to be one of the gentlemen on “Heated Rivalry,” but if I were to really dig into the archives it would be pre-Star Trek Chris Pine. I first saw him in an absolute train wreck of a movie called “Blind Dating” where he plays a blind guy who tries to pretend to be sighted in order to date. The movie was terrible, but I found him irresistible.

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I went suddenly deaf on one side only (my left) just before my 33rd birthday. After a bit of time in the wilderness (metaphorically) I got a cochlear implant a few years later, and it really changed my life. I will talk until someone stops me about hearing, sound, and the amazing arena of hearing loss technology. A lot of people, when they see my implant, assume I was born with hearing loss, so it’s always a bit odd (obscure even!) when I tell people I lost it as an adult. But, I also got my hearing back as an adult and am an eager advocate for assistive technology and visibility for people with disabilities that are not always immediately visible. I also work with prospective adult implant candidates to determine if an implant is right for them, because losing hearing suddenly as an adult is isolating and it’s helpful to talk to someone who’s been there.

Gabriel Acevero

Age: 35

Occupation: Maryland State Delegate

How do you identify? Gay

What are you looking for in a mate? Emotional intelligence and a sense of humor.

Biggest turn off: Fetishization.

Biggest turn on: Kindness and emotional intelligence.

Hobbies: Traveling and reading (I love books).

What is your biggest goal for 2026? More self care. I love what I do but it can also be physically taxing. In 2026, I’m prioritizing more self care.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I have neither but I’m open to both.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? No.

Celebrity crush: Kofi Siriboe

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I’m a Scorpio who was raised by a Scorpio and I have many Scorpios in my life.

Vida Rangel

Age: 36

Occupation: Public Servant, Community Organizer

How do you identify? I am a queer transLatina

What are you looking for in a mate? I’m looking for a partner who is caring, socially aware, and passionate about meaningfully improving some part of this world we all live in. Ideally someone playful who can match my mischievous energy, will sing and dance with me whenever joy finds us, and will meet me at protests and community meetings when the moment calls for bold collective action.

Biggest turn off: Ego. Confidence can be cute, but humility is sexy.

Biggest turn on: Drive. Seeing someone put their heart into pursuing their goals is captivating. Let’s chase our dreams together!

Hobbies: Music in all its forms (karaoke, playing guitar, concerts, musicals…), finding reasons to travel to new places, and making (Mexican) tamales for friends and coworkers.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? My biggest goal for 2026 is to organize and a celebratory kiss on election night wouldn’t hurt.

Pets, Kids or Neither? An adorable black cat named Rio (short for Misterio)

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? Ma’am? If you feel the need to ask…

Celebrity crush: Mi amor, Benito Bad Bunny. Zohran Mamdani, too. I have lots of love to give.

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I worked at Chick-fil-A when I was in high school and was fired after just three months. At the time it was still legal to fire someone for being trans, but I’m pretty sure it was because I called out to go to a Halloween party.

Em Moses

Age: 34

Occupation: Publishing

How do you identify? Queer

What are you looking for in a mate? Companionship, passion, fun. I seek a confident partner who inspires me, someone to laugh and dance with, someone with a rich internal universe of interests and experiences to build upon. A lifelong friend.

Biggest turn off: Dishonesty.

Biggest turn on: I love when someone is exactly themselves, nurturing their passions and skills and showing up uniquely in this world as only they can.

Hobbies: I love to read. I create art with my hands. When the weather is nice I’m outside, walking around the District looking at flowers and trees.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? My main goal this year is to spend more time with my nieces and nephews.

Pets, Kids or Neither? No pets or children in my life currently.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? While I consider myself quite openminded and genuinely enjoy learning from perspectives different from my own, I have clear boundaries around my morals and those pillars do not fall.

Celebrity crush: Luigi Mangione

Name one obscure fact about yourself: My first job was at a donut shop.

Nate Wong

Age: 41

Occupation: Strategy adviser to nonprofits and philanthropists to help ambitious ideas turn into meaningful, positive societal impact.

How do you identify? Gay (he/him)

What are you looking for in a mate? An additive partner: sociable, adventurous, and curious about the world. I’m drawn to warmth, openness, and people who show up fully — one-on-one and in community. If you enjoy a good dinner party, make eye contact, and actually talk to strangers (I know a D.C. no-no), we’ll get along just fine.

Biggest turn off: Not being present. Active listening matters to me; attention is a form of respect (and honestly, very attractive). And a picky food eater (how will we some day be joint food-critics?).

Biggest turn on: Curiosity, adventuresome spirit, and someone who can hold their own in a room — and still make others feel at ease. Confidence is best when it’s generous.

Hobbies: Splitting my time between the ceramics studio (District Clay), planning the next trip, and finding great food spots. I box to balance it all out, and I love curating small, adventurous gatherings that bring interesting people together — the kind where you stay later than planned.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? The last few years threw some curve balls. So 2026 is all about moving forward more freely and passionately, trusting what feels right and following it with intention (and joy).

Pets, Kids or Neither? Open to kids (in a variety of forms — already have some adorable god kids). A hypoallergenic dog would absolutely raise the cuddle quotient; cats are best admired from a respectful, allergy-safe distance.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? I value thoughtful listening and sincere debate; shared values around the honoring of everyone’s humanity, equity, and justice matter to me and aren’t up for debate.

Celebrity crush: Bad Bunny style with Jason Momoa humble confidence (harking to my Hawaiian roots) and Idris Elba charm — range matters.

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I celebrated medical clearance by going surfing in El Salvador. I’ve also nearly been arrested in Mozambique and somehow walked away unscathed (and without complying with a bribe) — happy to explain over an excursion.

Diane D’Costa

Age: 29

Occupation: Artist + Designer

How do you identify? Queer/lesbian

What are you looking for in a mate? A cuddle buddy, a fellow jet setter, a muse! Someone to light my soul on fire (in a good way).

Biggest turn off: Apathy. I care deeply about a lot of things and need someone with a similar curiosity and zest for life.

Biggest turn on: Mutuality really does it for me — a push and pull, someone who will throw it back and also catch it. I love someone who takes initiative, shows care and compassion, and expresses fluidity and confidence.

Hobbies: You can find me throwing pottery, painting, sipping natural wine, supporting local coffee shops, and most definitely tearing up a QTBIPOC dance floor.

What is your biggest goal for 2026? Producing my first solo art show. This year I’m really leaning into actualizing all my visions and dreams and putting them out into the world.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I’ve got a Black Lab named Lennox after the one and only D.C. icon, Ari Lennox. I love supporting the youth and (made a career out of it), but don’t necessarily need to have little ones of my own.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? No. Values alignment is key, but if you wanna get into the nuances of how we actualize collective liberation let’s get into it.

Celebrity crush: Queen Latifah

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I’m in the “Renaissance” movie. I know, I know slight flex… but “Crazy In Love” bottom left corner for a split second and a harsh crop, but I’m in there. “You are the visuals, baby” really hit home for me.

Donna Marie Alexander

Age: 67

Occupation: Social Worker

How do you identify? Lesbian

What are you looking for in a mate? Looking for a smart, kind, emotionally grown woman who knows who she is and is ready for real companionship. Also, great discernment and a good lesbian processor. Bonus points if you’ll watch a game with me— or at least cheer when I do. Extra bonus if you already know that women’s sports matter.

Ideal first date: Out for tea or a Lemon Drop that turns into dinner, great conversation, and a few laughs. Low drama, high warmth.

Must haves: A sense of humor, curiosity about the self, curiosity about me, and curiosity about the world. An independence, and an appreciation for loyalty—on and off the field. Dealbreaker: Anyone who thinks “it’s just a game.”

Biggest turn off: Self-centered and a lack of discernment.

Biggest turn on: Great conversation and a sense of humor.

Hobbies: Watching the Commanders game

What is your biggest goal for 2026? Self-growth and meeting an amazing friend.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I have two kids and grandkids.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? No

Celebrity crush: Pam Grier

Name one obscure fact about yourself: She’s way more superstitious about game-day routines than she lets on

Joe Reberkenny

Age: 24

Occupation: Journalist

How do you identify? Gay

What are you looking for in a mate? Someone who’s driven, flexible, and independent. I’m a full-time journalist so if there’s news happening, I’ve gotta be ready to cover breaking stories. I’m looking for someone who also has drive in their respective career and is always looking to the future. I need someone who gets along with my friends. My friends and community here are so important to me and I’m looking for someone who can join me in my adventures and enjoys social situations.

Biggest turn off: Insecurity and cocky men. Guys who can’t kiki with the girls. Early bedtimes.

Biggest turn on: Traits: Emotional stability and reliability. A certain sense of safety and trust. Someone organized and open to trying new things. Physical: Taller than I am (not hard to do at 5’7″) but also a preference for hairy men (lol). Someone who can cook (I am a vegetarian/occasional pescatarian and while it’s not a requirement for me in a partner it would need to be something they can accommodate).

Hobbies: Exploring D.C. — from museums to nightlife, reading (particularly interested in queer history), dancing, frolicking, playing bartender, listening to music (preferably pop), classic movie connoisseur (TCM all the way).

What is your biggest goal for 2026? Continue my work covering LGBTQ issues related to the federal government, uplift queer voices, see mother monster (Lady Gaga) in concert.

Pets, Kids or Neither? I’ve got neither but I love a pet.

Would you date someone whose political views differ from yours? No

Celebrity crush: Pedro Pascal

Name one obscure fact about yourself: I’ve been hit by multiple cars and I have a twin sister.

a&e features

Marc Shaiman reflects on musical success stories

In new memoir, Broadway composer talks ‘Fidler,’ ‘Wiz,’ and stalking Bette Midler

If you haven’t heard the name Marc Shaiman, you’ve most likely heard his music or lyrics in one of your favorite Broadway shows or movies released in the past 50 years. From composing the Broadway scores for Hairspray and Catch Me if You Can to most recently working on Only Murders in the Building, Hocus Pocus 2, and Mary Poppins Returns, the openly queer artist has had a versatile career — one that keeps him just an Oscar away from EGOT status.

The one thing the award-winning composer, lyricist, and writer credits with launching his successful career? Showing up, time and time again. Eventually, he lucked out in finding himself at the right place at the right time, meeting industry figures like Rob Reiner, Billy Crystal, and Bette Midler, who were immediately impressed with his musical instincts on the piano.

“Put my picture under the dictionary definition for being in the right place at the right time,” Shaiman says. “What I often try to say to students is, ‘Show up. Say yes to everything.’ Because you never know who is in the back of the theater that you had no idea was going to be there. Or even when you audition and don’t get the part. My book is an endless example of dreams coming true, and a lot of these came true just because I showed up. I raised my hand. I had the chutzpah!”

Recalling one example from his memoir, titled Never Mind the Happy: Showbiz Stories from a Sore Winner ( just hit bookshelves on Jan. 27), Shaiman says he heard Midler was only hiring Los Angeles-based artists for her world tour. At the young age of 20, the New York-based Shaiman took a chance and bought the cheapest flight he could find from JFK. Once landing in L.A., he called up Midler and simply asked: “Where’s rehearsal?”

“Would I do that nowadays? I don’t know,” Shaiman admits. “But when you’re young and you’re fearless … I was just obsessed, I guess you could say. Maybe I was a stalker! Luckily, I was a stalker who had the goods to be able to co-create with her and live up to my wanting to be around.”

On the occasion of Never Mind the Happy’s official release, the Bladehad the opportunity to chat with Shaiman about his decades-spanning career. He recalls the sexual freedom of his community theater days, the first time he heard someone gleefully yell profanities during a late screening of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and why the late Rob Reiner was instrumental to both his career and his lasting marriage to Louis Mirabal. This interview has been edited and condensed.

BLADE: Naturally, a good place to start would be your book, “Never Mind the Happy.” What prompted you to want to tell the story of your life at this point in your career?

SHAIMAN: I had a couple of years where, if there was an anniversary of a movie or a Broadway show I co-created, I’d write about it online. People were always saying to me, “Oh my God, you should write a book!” But I see them say that to everybody. Someone says, “Oh, today my kitten knocked over the tea kettle.” “You should write a book with these hysterical stories.” So I just took it with a grain of salt when people would say that to me. But then I was listening to Julia Louis-Dreyfus’ podcast, and Jane Fonda was on talking about her memoir — not that I’m comparing myself to a career like Jane Fonda’s — but she felt it was time to take a life review. That really stuck in my head. At the time, I was sulking or moping about something that had not gone as well as I wished. And I guess I kind of thought, “Let me look back at all these things that I have done.” Because I have done a lot. I’m just weeks short of my 50th year in show business, despite how youthful I look! I just sat down and started writing before anyone asked, as far as an actual publisher.

I started writing as a way to try to remind myself of the joyous, wonderful things that have happened, and for me not to always be so caught up on what didn’t go right. I’ve been telling some of these stories over the years, and it was really fun to sit down and not just be at a dinner party telling a story. There’s something about the written word and really figuring out the best way to tell the story and how to get across a certain person’s voice. I really enjoyed the writing. It was the editing that was the hard part!

BLADE: You recall experiences that made you fall in love with the world of theater and music, from the days you would skip class to go see a show or work in regional productions. What was it like returning to those early memories?

SHAIMAN: Wonderful. My few years of doing community theater included productions that were all kids, and many productions with adults, where I was this freaky little 12-year-old who could play show business piano beyond my years. It was just bizarre! Every time a director would introduce me to another cast of adults, they’d be like, “Are you kidding?” I’d go to the piano, and I would sightread the overture to Funny Girl, and everybody said, “Oh, OK!” Those were just joyous, wonderful years, making the kind of friends that are literally still my friends. You’re discovering musical theatre, you’re discovering new friends who have the same likes and dreams, and discovering sex. Oh my god! I lost my virginity at the opening night of Jesus Christ Superstar, so I’m all for community theater!

BLADE: What do you recall from your early experiences watching Broadway shows? Did that open everything up for you?

SHAIMAN: I don’t remember seeing Fiddler on the Roof when I was a kid, but I remember being really enthralled with this one woman’s picture in the souvenir folio — the smile on her face as she’s looking up in the pictures or looking to her father for approval. I always remember zooming in on her and being fascinated by this woman’s face: turns out it was Bette Midler. So my love for Bette Midler began even before I heard her solo records.

Pippin and The Wiz were the first Broadway musicals I saw as a young teenager who had started working in community theater and really wanted to be a part of it. I still remember Pippin with Ben Vereen and all those hands. At the time, I thought getting a seat in the front row was really cool — I’ve learned since that it only hurts your neck, but I remember sitting in the front row at The Wiz as Stephanie Mills sang Home. Oh my god, I can still see it right now. And then I saw Bette Midler in concert, finally, after idolizing her and being a crazed fan who did nothing but listen to her records, dreaming that someday I’d get to play for her. And it all came true even before I turned 18 years old. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time, and met one of her backup singers and became their musical director. I was brought to a Bette Midler rehearsal. I still hadn’t even turned 18, she heard me play and said, “Stick around.” And I’ve stuck around close to 55 years! She’s going to interview me in L.A. at the Academy Museum. Would I have ever thought that Bette Midler would say yes to sitting with me, interviewing me about my life and career?

BLADE: That’s amazing. Has she had a chance to read the book yet?

SHAIMAN: She read it. We just talked yesterday, and she wants to ask the right questions at the event. And she even said to me, “Marc, I wasn’t even aware of all that you’ve done.” We’ve been great friends for all these years, but sometimes months or almost years go by where you’re not completely in touch.

a&e features

D.C. LGBTQ sports bar Pitchers listed for sale

Move follows months of challenges for local businesses in wake of Trump actions

A Santa Monica, Calif.-based commercial real estate company called Zacuto Group has released a 20-page online brochure announcing the sale of the D.C. LGBTQ sports bar Pitchers and its adjoining lesbian bar A League of Her Own.

The brochure does not disclose the sale price, and Pitchers owner David Perruzza told the Washington Blade he prefers to hold off on talking about his plans to sell the business at this time.

He said the sale price will be disclosed to “those who are interested.”

“Matthew Luchs and Matt Ambrose of the Zacuto Group have been selected to exclusively market for sale Pitchers D.C., located at 2317 18th Street, NW in Washington, D.C located in the vibrant and nightlife Adams Morgan neighborhood,” the sales brochure states.

“Since opening its doors in 2018, Pitchers has quickly become the largest and most prominent LGBTQ+ bar in Washington, D.C., serving as a cornerstone of D.C.’s modern queer nightlife scene,” it says, adding, “The 10,000+ SF building designed as a large-scale inclusive LGBTQ+ sports bar and social hub, offering a welcoming environment for the entire community.”

It points out that the Pitchers building, which has two years remaining on its lease and has a five-year renewal option, is a multi-level venue that features five bar areas, “indoor and outdoor seating, and multiple patios, creating a dynamic and flexible layout that supports a wide range of events and high customer volume.”

“Pitchers D.C. is also home to A League of Her Own, the only dedicated lesbian bar in Washington, D.C., further strengthening its role as a vital and inclusive community space at a time when such venues are increasingly rare nationwide,” the brochure says.

Zacuto Group sales agent Luchs, who serves as the company’s senior vice president, did not immediately respond to a phone message left by the Blade seeking further information, including the sale price.

News of Perruzza’s decision to sell Pitchers and A League of Her Own follows his Facebook postings last fall saying Pitchers, like other bars in D.C., was adversely impacted by the Trump administration’s deployment of National Guard soldiers on D.C. streets

In an Oct. 10 Facebook post, Perruzza said he was facing, “probably the worst economy I have seen in a while and everyone in D.C. is dealing with the Trump drama.” He told the Blade in a Nov. 10 interview that Pitchers continued to draw a large customer base, but patrons were not spending as much on drinks.

The Zacuto Group sales brochure says Pitchers currently provides a “rare combination of scale, multiple bars, inclusivity, and established reputation that provides a unique investment opportunity for any buyer seeking a long-term asset with a loyal and consistent customer base,” suggesting that, similar to other D.C. LGBTQ bars, business has returned to normal with less impact from the Trump related issues.

The sales brochure can be accessed here.