Opinions

Throwaway people in our midst

‘Just Mercy’ helps change the narrative on criminal justice

I recently met a grizzled panhandler walking along 16th Street in downtown Washington. He was cursing that nobody would hire him because of his criminal record. He told me that he slept in an alley, and pointed to a trash can that he had searched four times that day.

He was afraid of dying in the cold, but didn’t feel safe in homeless shelters, so he carried a knife. Somehow I was less concerned about a convict with a knife walking beside me than about the fellow five blocks south, without a conviction, who joked and complained on the same afternoon about being impeached.

Why did that homeless man return to the same trash can several times a day? It was beside a stream of people who could afford to waste food. Not only was he familiar with the most promising trash cans, he knew the locations of several ATMs where kind souls could get him cash. Such is the life of a street survivor in our throwaway culture.

“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view, until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” So said Gregory Peck’s Atticus Finch to his daughter Scout in 1962’s To Kill a Mockingbird. His performance as the quintessential white savior defending a wrongly accused black man won him an Oscar and inspired many people to become lawyers. His halo was snatched away when Harper Lee’s novel Go Set a Watchman, published in 2015, revealed that Atticus served on the white supremacist Maycomb County Citizens’ Council.

Speaking of points of view, Mockingbird was perfectly designed to make white people in the civil rights era feel better about themselves. Six decades later, there is more diversity among filmmakers. The current movie Just Mercy, starring Michael B. Jordan and Jamie Foxx, which also concerns an unjustly accused black man, is partly set in Monroeville, Alabama, the real place that inspired the fictional Maycomb. This true story, however, is told from a black perspective. A black sensibility permeates the film.

The contrast between Bryan Stevenson‘s meeting with the wrongly convicted man’s family and the comparable scene in Mockingbird is telling: in Just Mercy, the defense attorney is not just paying his respects but seeking input. In Mockingbird, polite Negroes are plentiful on the porch and in the courtroom balcony. In Just Mercy, black people are active participants: they have agency. The danger Stevenson faces as a black attorney from Harvard, just by being there and persisting, is palpable. The portrayal of the prisoners whose cells are next to that of Foxx’s Walter McMillian is as humane as I have seen.

Stevenson says, “We have a system of justice that treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent.” According to the Equal Justice Initiative, which he founded, “Mr. Stevenson and his staff have won reversals, relief, or release from prison for over 135 wrongly condemned prisoners on death row and won relief for hundreds of others wrongly convicted or unfairly sentenced.”

Reform is hard. As Paul Butler describes in Chokehold, “Ban the Box” policies (for which I myself testified in 2012) “prohibit employers from conducting criminal background checks until late in the application process. The hope was this would give people coming home from prison a better chance at landing an interview, but studies have shown that BTB policies have actually done more harm than good for black men. When employers don’t have actual information about whether people have a criminal background, they tend to assume that young African American men do.”

Butler writes, “The truth is that the vast majority of black men have never committed a violent crime. It’s a stereotype that … can be supported by a selective view of the evidence.”

The homeless, including former prisoners, transgender people, and veterans with PTSD, represent systemic failures, as in criminal justice. Filmic truth-telling like Just Mercy can further efforts like Stevenson’s to change the narrative.

Things are not always as we imagine. If we stop throwing our fellow human beings away, all of our streets can better reflect the society we have long told ourselves we are.

Richard J. Rosendall is a writer and activist at [email protected].

Copyright © 2020 by Richard J. Rosendall. All rights reserved.

Opinions

Successful open relationships take effort

We have options as couples but they all require work

(Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part feature on open relationships. Click here for last week’s installment.)

Open relationships are often ridiculed as the easy way out of commitment. After speaking with Scott and Kelsey, however, it’s clear they’re anything but easy.

Kelsey reflected on the ups and downs of being open in the past. “Younger me definitely needed it,” Kelsey said. “At the same time, drama came with it as well.”

While Scott and their partner have been together for nine years, it took four before they decided to open their relationship. “It came from the desire for the two of us to meet boys together,” said Scott. “Then we had some really terrible threesomes.”

Drama. Bad threesomes. Yikes – these aren’t exactly selling points for being open. But their experiences underscore something important: open relationships, like all relationships, are actually quite hard. Couples considering openness shouldn’t trick themselves into thinking it will make things easier. In reality, they take a lot of work.

For Scott, those really terrible threesomes led them to opening up further, but with established boundaries. “We came up with ground rules. Use protection. No spending the night at somebody’s house, etc.”

Since Scott and their partner are happy in their relationship, these rules seem to work even if they’ve shifted over time. “Being in an open relationship comes down to being really good at communicating with your partner,” they added. “It’s about communicating and checking in to see where your partner is.”

Open relationships should be for the right reasons

As open relationships began taking off, observers were skeptical for good reason. “In the past, people were just cheating,” said Kelsey. Another comment from Scott echoed this. “I’ve seen open relationships and it felt like one partner was being taken advantage of by the other.”

It turns out there is a fine line between sexual exploration and free passes. While some open relationships walk that line well, others – not so much.

In all fairness, now more than ever it’s difficult to remain monogamous, and one culprit is the rise of accessible hookup culture via social media. Apps like Tinder, Grindr, and dare I say Instagram are facilitating secret sexual connections never seen before. They ushered in a new era of cheating into relationships, alongside a bit of excessive stalking as well.

So, to avoid an atmosphere of mistrust and pain, a natural evolution for couples is to change the rules altogether. Cheating can’t be cheating if it’s allowed, right?

However, once it is allowed, I wondered why these people don’t cut the strings altogether and be single. In response, Chad made an interesting point: people aren’t just afraid of being cheated on – they’re afraid of the appearance of being single as well. We live in flashy times where our online image means everything. The dream is not necessarily having a partner, but showing the world you have a partner. Without that, you otherwise appear lonely.

So, do open relationships ease the pain of cheating and perceived loneliness? As a proud lone wolf I’m not the best person to assess, but based on my observations I can say this: being open works for some couples, but by no means is it a fast pass to being happy. Understanding why you want one is just as important as discovering how to make one work.

With all this said, the undeniable risk – and perhaps downside – of a monogamous coupling is the higher chance of cheating outright. Unfortunately, that’s something Chad knows all too well.

Preferring monogamy is still OK

Chad had dated someone for two years before they married for five. Then, just over a year into the pandemic, his husband informed him he was dating someone else. They separated a few days later.

For Chad this was painful, as it is for anyone, gay or straight, who’s gone through something similar. But when I asked him if this experience shaped his outlook on what he’s looking for, his response came as a bit of a surprise:

“It has not changed my view for or against open relationships,” he said. “I learned a lot in my marriage. It takes a lot of love, trust, and communication, which at times can feel like work. It also takes two; one can’t carry the relationship. I want to date someone who wants to be in a relationship with me.”

My heart swells hearing that, for even after experiencing the deepest kind of hurt, Chad searches for his one and only. Why? Because for him, the love he’s looking for is worth the wait. It’s a beautiful sentiment that makes so-called hopeless romanticism the raddest feeling in the world sometimes.

More importantly, Chad doesn’t let fear alter his view on love, and to me that’s the most important lesson of this article. Love always comes with risks, and lowering your standards to reduce them never really pans out, does it? The best we can do is to be ourselves.

By the way, this is a lesson I should also apply. My main hesitation toward an open relationship is that I’m a jealous bitch, and I fear that jealousy will never go away. Yet this can be hard to admit when everyone around you is propping up a culture where open is supreme and jealousy is immature.

When I brought this up to Kelsey, she pushed back with a simple question: “Do you think jealousy is a bad thing?”

This caught me off guard. “I’m not sure,” I replied. “Do you?”

“Jealousy is a natural, human emotion,” she said. “It’s what you do with it that matters.”

So, maybe my goal is not to suppress my jealousy but rather be upfront about it. If it’s part of me, I should own it, then ideally find someone who loves me regardless.

Changing your mind is OK, too

In gay man speak, I was a top for my first seven years before I embraced bottoming. For some, they’d be shocked to hear it. Yet maybe no one should be surprised, for as we all know sexuality is fluid, and this applies to more than just your orientation. Your sexual preferences can shift over time, too, and this will inevitably affect your relationships.

This was the case for Scott and their partner. “When we first started dating, we did not want to be open,” they mentioned, “but as our relationship grew, we decided to reevaluate that.” Meanwhile, Kelsey went the opposite direction – she was open back in the day but chooses to be closed now.

Even Chad remains open to being open. “I’m not opposed to an open relationship, but I feel like it would take more work. I just don’t see myself starting a relationship open. The first few years there is a lot of learning about each other.”

In a world of shifting preferences, the best we can do is reflect on what we want and be honest about it. Life is a process of discovering who we are, and damn is it messy. So, perhaps I should cut some slack to the couple trying things out. And perhaps they can cut me slack for not understanding their rules.

For the couples: remember, a solid relationship is not only about meeting the needs of your partner, because your needs matter, too. The best relationships, open or closed, strive to find that balance.

For those still searching: remember that love is more than just that thing, that connection, that spark. In fact, love is so complex that the “spark” is just one of many factors, alongside timing and how you want to be loved, that come together and form an imprint as unique and special as the person you want to be with.

In this sense, open and closed relationships aren’t diametrically opposed but rather complimentary, a sort of yin and yang where both become better because the other option exists. Today, we have options as couples, and that’s significantly better than abiding by rules because we assume that’s how it must be.

And that feels right. Because regardless of whether you’re more a Chad or a Scott, the truth is: I feel lucky to have both.

(Writer’s note: A big thank you you to Chad, Scott, and Kelsey for allowing me to share their stories.)

Jake Stewart is a D.C.-based writer and barback.

Opinions

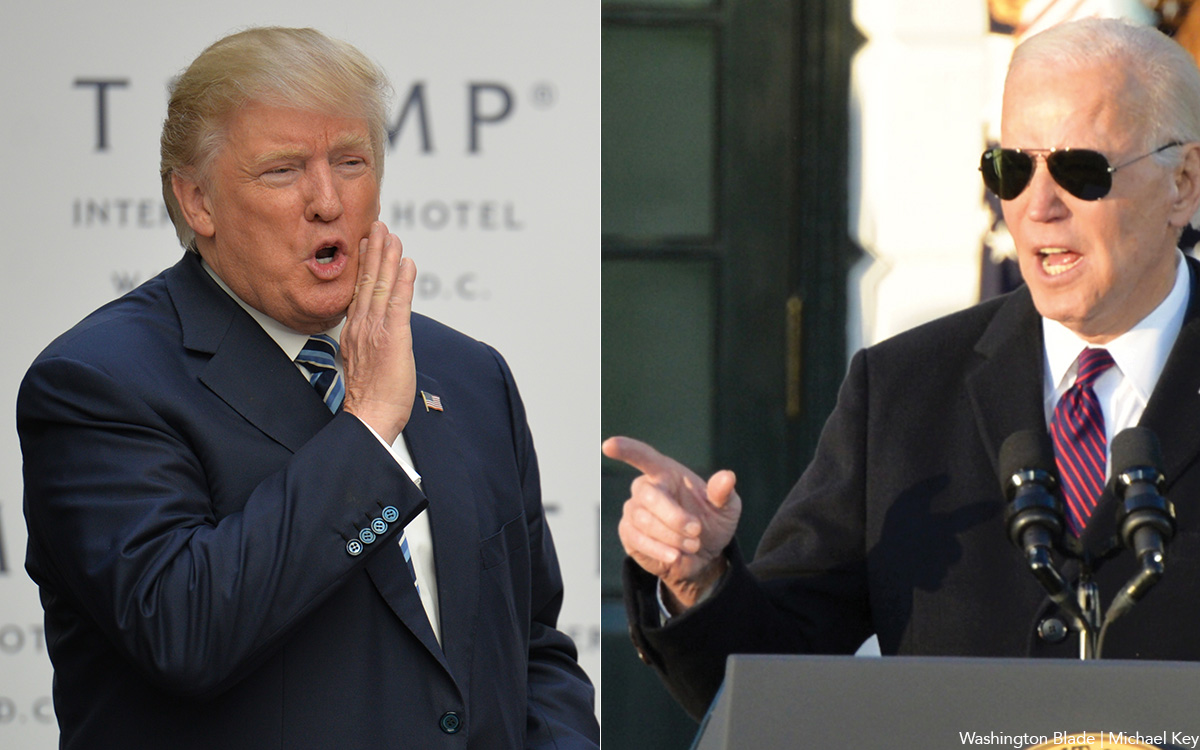

Fact: The next president will be Biden or Trump

One candidate is clearly better for the future of the world

Like it or not, the next president will be either Joe Biden or Donald Trump. In our system, third-party candidates are simply spoilers, they don’t win. The last time a third-party candidate won was 1856. It has been 36 years since a third-party candidate even got more than 5% of the vote. So, it’s time to face reality and choose; for your future, do you want Biden or Trump?

I was prompted to write this column because I see the media interviewing young people about who they want as their president. I have great respect for the young people of today. In many ways, they are smarter than my generation was. But it’s clear, some don’t fully understand the presidential election process. I hear many complain about Biden, and then follow that up and say they will never vote for Trump. Some then say they will vote for a third-party candidate. They need to understand their third-party candidate will not win, but their vote could help elect Trump. I hate to say it, but in 2024, voting for a third-party candidate is the equivalent to flushing your ballot down the toilet.

I am an unabashed Biden supporter. I see the great things he has done, including: getting us through the fallout from the pandemic, passing an infrastructure bill, forgiving billions in student loans, ensuring our economy is the best in the world with more than 13 million jobs created, and increasing wages. He supports unions, being the first president to walk a picket line with the UAW. His administration is working to deal with climate change. He is fighting for a woman’s right to control her own body and healthcare, and supports full equality for the LGBTQ community. In this dangerous world he has kept our troops out of war.

Then there is Trump. To be clear; I see him as a racist, sexist, misogynistic, homophobic, pig. OK, so maybe I don’t have strong feelings about him. Trump has been found liable for sexual assault and has been indicted on 91 counts. He proudly claims credit for having taken away control of their body and healthcare from women, when the justices he appointed ended Roe v. Wade. He supports states making decisions on abortion, and we see what recently happened in Arizona. He is a climate change denier and is opposed to wind and solar power. He wants to give more tax deductions to the rich and to corporations, while opposing any increase in the minimum wage. He opposes equality for the LGBTQ community, refusing to endorse the Equality Act. He opposes student debt relief.

You may see these candidates differently, and that is OK. But if you like one more than the other, fear one more than the other, or just aren’t enamored by either, you must still make a choice and vote for one of them. Staying home is abrogating your civic responsibility, and especially if you would never vote for Trump, understand your staying home helps him.

Young voters, like all voters, should take the time to do the research on both candidates. Then match what you find as close as possible to what you want to see as your future. If you want student loan relief, equality for the LGBTQ community, women having control of their body and healthcare, equal pay for women, efforts to ameliorate the impact of climate change, then clearly Trump is not your candidate.

I hear some young people say they won’t vote for Biden because of his positions on the Israel/Hamas war. I, too, have called for Israel to recalibrate how they fight this war. But I ask you to look again at Trump’s history of attachment to Netanyahu, even going so far as relocating the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem. If you want a chance for the Palestinian people to live in peace and prosperity, for Israel to remove their settlements from the West Bank, your chance of having that happen is clearly better with Biden than Trump. Don’t let your emotions today, cloud the reality of the future.

Yes, Biden is old, but so is Trump. He apparently can’t even stay awake at his own trial having nodded off two days in a row. So, since one of them will be president, with no third-party candidate having a chance, I urge you to look at them again, in a realistic way. Then make your choice. I think you may come to the same conclusion I have. Though not perfect, and no one is, Biden is the better candidate for your future, and for the future of the world.

Peter Rosenstein is a longtime LGBTQ rights and Democratic Party activist. He writes regularly for the Blade.

In 2023, the law was signed to expand the District’s medical cannabis program. It also made permanent provisions allowing residents ages 21 and older to self-certify as medical cannabis patients. Overall, cannabis is fully legal in D.C. for medical and recreational use, and 4/20 Day is widely celebrated.

Medical cannabis, for example, has a long history with the LGBTQ community, and they have often been one of the oldest supporters of marijuana and some of the most enthusiastic consumers. Cannabis use also has a long history of easing the pain of the LGBTQ community as relief from HIV symptoms and as a method of coping with rejection from society.

The cannabis culture continues to grow in the District, and as a result, so does the influence on younger people, even youth within the LGBTQ community. Drug education can play an important role and should not be avoided during 4/20 Day. Parents and educators can use drug education to help their kids understand the risks involved with using marijuana at a young age.

According to DC Health Matters, marijuana use among high school students has been on the decline in the District since 2017. In 2021, it was estimated that around 20% of high school students use marijuana, a drop from 33% in 2017. Nationally, in 2020, approximately 41.3% of sexual minority adults 18 and older reported past-year marijuana use, compared to 18.7% of the overall adult population.

When parents and educators engage with their kids about marijuana, consider keeping the conversations age appropriate. Speaking with a five-year-old is much different than speaking with a teenager. Use language and examples a child or teen would understand.

The goal is to educate them about the risks and dangers of using cannabis at a young age and what to avoid, such as edibles.

Most important, put yourself in your kid’s shoes. This can be especially important for teenagers as they face different social pressures and situations at school, with peer groups, or through social media. Make a point of understanding what they are up against.

When speaking to them about cannabis, stay calm and relaxed, stay positive, don’t lecture, and be clear and concise about boundaries without using scare tactics or threats.

Yet, it’s OK to set rules, guidelines, and expectations; create rules together as a family or class. Parents and educators can be clear about the consequences without lecturing but clearly stating what is expected regarding cannabis use.

Moreover, choose informal times to have conversations about cannabis and do not make a big thing about it. Yet, continue talking to them as they age, and let them know you are always there for them.

Finally, speak to them about peer pressure and talk with them about having an exit plan when they are offered marijuana. Peer pressure is powerful among youth, and having a plan to avoid drug use helps children and students make better choices. Ultimately, it is about assisting them in making good choices as they age.

Members of the LGBTQ community often enter treatment with more severe substance use disorders. Preventative measures involving drug education are effective in helping youth make good choices and learn about the risks.

Marcel Gemme is the founder of SUPE and has been helping people struggling with substance use for over 20 years. His work focuses on a threefold approach: education, prevention, and rehabilitation.

-

District of Columbia3 days ago

District of Columbia3 days agoCatching up with the asexuals and aromantics of D.C.

-

State Department5 days ago

State Department5 days agoState Department releases annual human rights report

-

South America3 days ago

South America3 days agoArgentina government dismisses transgender public sector employees

-

Maine4 days ago

Maine4 days agoMaine governor signs transgender, abortion sanctuary bill into law