Books

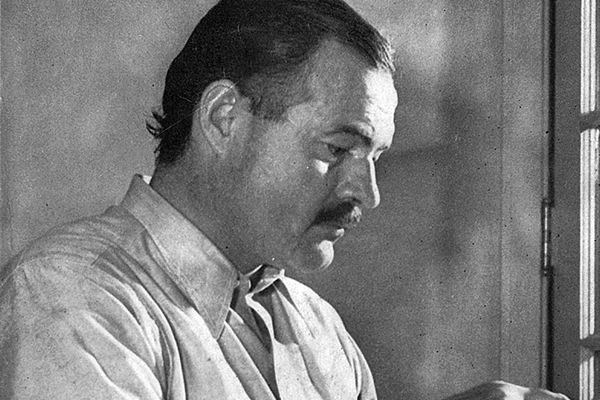

Hemingway: Brilliant writer or avatar of toxic masculinity?

New documentary breaks through the ‘Papa’ mystique

Ernest Hemingway’s work is widely available in print, e-book and audio formats.

“I went to the garage and cried when your Mom died,” my Dad told me a half century ago, “I didn’t want anyone to see me crying.”

“Men aren’t supposed to cry,” he added

“Why?” I asked.

“Read Hemingway,” he said, “ then you’ll know why.”

Decades later, we still avidly read Hemingway, who lived from 1899 to 1961.

We heatedly debate: Was Hemingway one of America’s greatest writers (a 20th century Mark Twain or Walt Whitman)? Or an avatar of toxic masculinity?

Gertrude Stein taught him about writing. Yet, in his work, he made homophobic references to “fairies.” He wrote with empathy of women dying in childbirth, while penning paragraph after paragraph about bullfights.

But, “Hemingway,” a new three-part documentary by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick streaming on PBS, makes Hemingway, with all his contradictions, come alive. Actors from Jeff Daniels to Patricia Clarkson to Meryl Streep bring Hemingway, his parents and wives (he was married four times) to life.

“Hemingway” reveals that Hemingway, the ultimate man’s man, was into androgyny – what we’d today call gender fluidity.

Hemingway’s story is well known. Born in Oak Park, Ill., he was a reporter with the Kansas City Star, before he enlisted as an ambulance driver in World War I. During the War, Hemingway was wounded and fell in love with a nurse, who rejected him.

He and his first wife Hadley Richardson moved to Paris in the early 1920s. There, Hemingway worked for a while as a reporter, then quit to become a “starving” writer. His hunger pangs enhanced his writing. “Hunger is good discipline,” he wrote in “A Moveable Feast,” his memoir of his time in Paris in the 1920s.

Actually, Hemingway wasn’t poor in Paris. Hadley had a trust fund. In Paris, Gertrude Stein and other writers mentored him. “The Sun Also Rises,” his first novel, published in 1926 was a critical and commercial success.

After that, Hemingway lived in Key West, Fla., and Cuba; and was a war correspondent in the Spanish Civil War and World War II. He received the Nobel Prize in literature in 1954. Everyone from Marlene Dietrich to GIs in World War II called him “Papa.”

At 61, he killed himself in Ketchum, Idaho, where he and his fourth wife Mary Welsh lived.

“Hemingway,” breaks through the “Papa” mystique. Hemingway’s father, suffering from depression, killed himself. (Hemingway would suffer from depression, traumatic brain injuries and alcoholism.) His mother Grace dressed Hemingway and his sister identically when they were young. She gave them toy rifles and dolls to play with.

Later, Hemingway and Welsh liked to switch roles in bed, says Mary V. Dearborn, author of a terrific bio of Hemingway.

Hemingway would be the girl and Welsh would be the boy. They cut their hair to the same length. “In a way, he wanted to be a woman in love with another woman,” Dearborn says.

Not surprisingly for his time, Hemingway was enraged when his son Greg (who was trans and later known as Gloria) was arrested in 1951 for wearing women’s clothing in a women’s restroom. The two later reconciled.

The documentary helped me understand why I love some of Hemingway’s work (“The Sun Also Rises,” “A Farewell to Arms,” “A Moveable Feast”).

For despite his he-man image, Hemingway writes movingly of love and death. Through his deceptively simple, repetitive sentences, he makes you feel life as you read. Hot off the page.

What we remember most from his books isn’t the wars or the bullfights. It’s Catherine dying in child birth in “A Farewell to Arms.”

It’s the woman in the short story “Hills Like Elephants.” Her boyfriend keeps trying to pressure her into having an abortion. “Please, please, please, please, please, please, please, would you just stop talking?” she says to him when he won’t stop mansplaining.

It’s David and Catherine, the couple in the posthumously published “The Garden of Eden,” who, defying convention, switch gender and sexual roles.

Hemingway is a writer for our moment, when we’re struggling with toxic masculinity and viewing gender in new ways. Check out “Hemingway,” on PBS online. Better yet, read one of Hemingway’s books.

Books

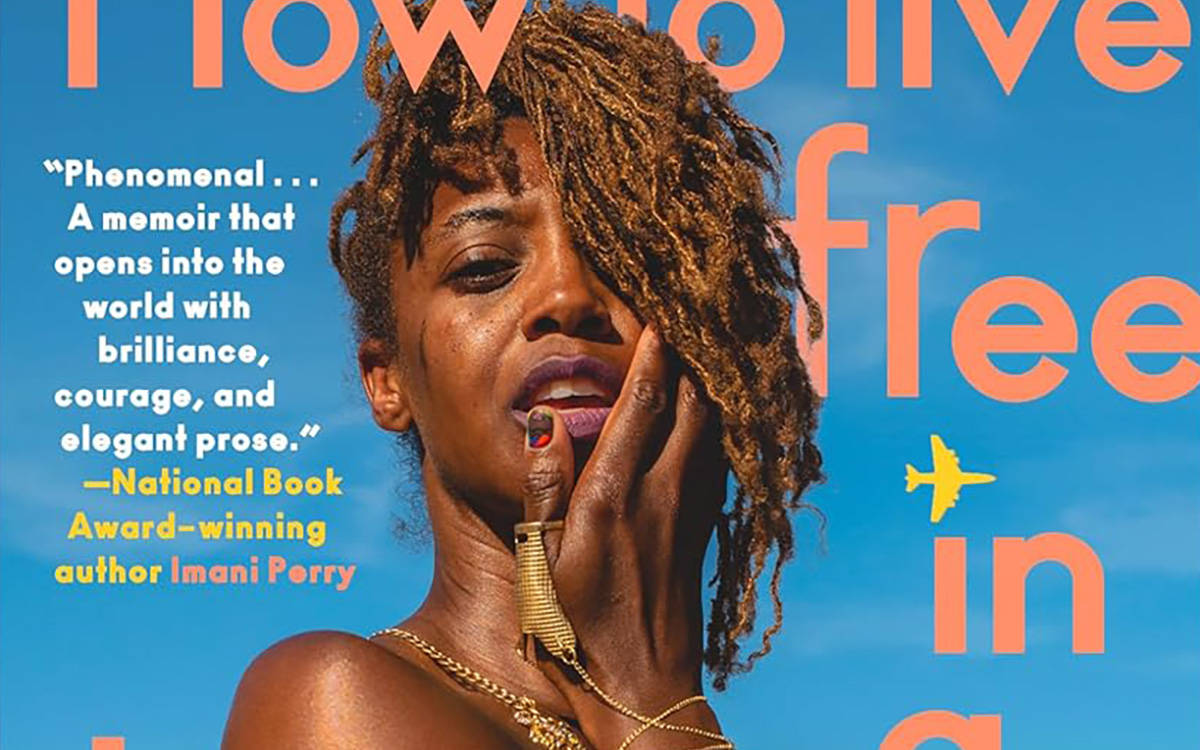

New book offers observations on race, beauty, love

‘How to Live Free in a Dangerous World’ is a journey of discovery

‘How to Live Free in a Dangerous World: A Decolonial Memoir’

By Shayla Lawson

c.2024, Tiny Reparations Books

$29/320 pages

Do you really need three pairs of shoes?

The answer is probably yes: you can’t dance in hikers, you can’t shop in stilettos, you can’t hike in clogs. So what else do you overpack on this long-awaited trip? Extra shorts, extra tees, you can’t have enough things to wear. And in the new book “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” by Shayla Lawson, you’ll need to bring your curiosity.

Minneapolis has always been one of their favorite cities, perhaps because Shayla Lawson was at one of Prince’s first concerts. They weren’t born yet; they were there in their mother’s womb and it was the first of many concerts.

In all their travels, Lawson has noticed that “being a Black American” has its benefits. People in other countries seem to hold Black Americans in higher esteem than do people in America. Still, there’s racism – for instance, their husband’s family celebrates Christmas in blackface.

Yes, Lawson was married to a Dutch man they met in Harlem. “Not Haarlem,” Lawson is quick to point out, and after the wedding, they became a housewife, learned the language of their husband, and fell in love with his grandmother. Alas, he cheated on them and the marriage didn’t last. He gave them a dog, which loved them more than the man ever did.

They’ve been to Spain, and saw a tagline in which a dark-skinned Earth Mother was created. Said Lawson, “I find it ironic, to be ordained a deity when it’s been a … journey to be treated like a person.”

They’ve fallen in love with “middle-American drag: it’s the glitteriest because our mothers are the prettiest.” They changed their pronouns after a struggle “to define my identity,” pointing out that in many languages, pronouns are “genderless.” They looked upon Frida Kahlo in Mexico, and thought about their own disability. And they wish you a good trip, wherever you’re going.

“No matter where you are,” says Lawson, “may you always be certain who you are. And when you are, get everything you deserve.”

Crack open the front cover of “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” and you might wonder what the heck you just got yourself into. The first chapter is artsy, painted with watercolors, and difficult to peg. Stick around, though. It gets better.

Past that opening, author Shayna Lawson takes readers on a not-so-little trip, both world-wide and with observant eyes – although it seems, at times, that the former is secondary to that which Lawson sees. Readers won’t mind that so much; the observations on race, beauty, love, the attitudes of others toward America, and finding one’s best life are really what takes the wheel in this memoir anyhow. Reading this book, therefore, is not so much a vacation as it is a journey of discovery and joy.

Just be willing to keep reading, that’s all you need to know to get the most out of this book. Stick around and “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World” is what to pack.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Story of paralysis and survival features queer characters

‘Unswerving: A Novel’ opens your eyes and makes you think

‘Unswerving: A Novel’

By Barbara Ridley

c.2024, University of Wisconsin Press

$19.95 / 227 pages

It happened in a heartbeat.

A split-second, a half a breath, that’s all it took. It was so quick, so sharp-edged that you can almost draw a line between before and after, between then and now. Will anything ever be the same again? Perhaps, but maybe not. As in the new book “Unswerving” by Barbara Ridley, things change, and so might you.

She could remember lines, hypnotizing yellow ones spaced on a road, and her partner, Les, asleep in the seat beside her. It was all so hazy. Everything Tave Greenwich could recall before she woke up in a hospital bed felt like a dream.

It was as though she’d lost a month of her life.

“Life,” if you even wanted to call it that, which she didn’t. Tave’s hands resembled claws bent at the wrist. Before the accident, she was a talented softball catcher but now she could barely get her arms to raise above her shoulders. She could hear her stomach gurgle, but she couldn’t feel it. Paralyzed from the chest down, Tave had to have help with even the most basic care.

She was told that she could learn some skills again, if she worked hard. She was told that she’d leave rehab some day soon. What nobody told her was how Les, Leslie, her partner, girlfriend, love, was doing after the accident.

Physical therapist Beth Farringdon was reminded time and again not to get over-involved with her patients, but she saw something in Tave that she couldn’t ignore. Beth was on the board of directors of a group that sponsored sporting events for disabled athletes; she knew people who could serve as role models for Tave, and she knew that all this could ease Tave’s adjustment into her new life. It was probably not entirely in her job description, but Beth couldn’t stop thinking of ways to help Tave who, at 23, was practically a baby.

She could, for instance, take Tave on outings or help find Les – even though it made Beth’s own girlfriend, Katy, jealous.

So, here’s a little something to know before you start reading “Unswerving”: author Barbara Ridley is a former nurse-practitioner who used to care for patients with spinal cord injuries. That should give readers a comfortable sense of satisfaction, knowing that her experiences give this novel an authenticity that feels right and rings true, no faking.

But that’s not the only appeal of this book: while there are a few minor things that might have readers shaking their heads (HIPAA, anyone?), Ridley’s characters are mostly lifelike and mostly likable. Even the nasties are well done and the mysterious character that’s there-not-there boosts the appeal. Put everyone together, twist a little bit to the left, give them some plotlines that can’t ruined by early guessing, and you’ve got a quick-read novel that you can enjoy and feel good about sharing.

And share you will because this is a book that may also open a few eyes and make readers think. Start “Unswerving” and you’ll (heart) it.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

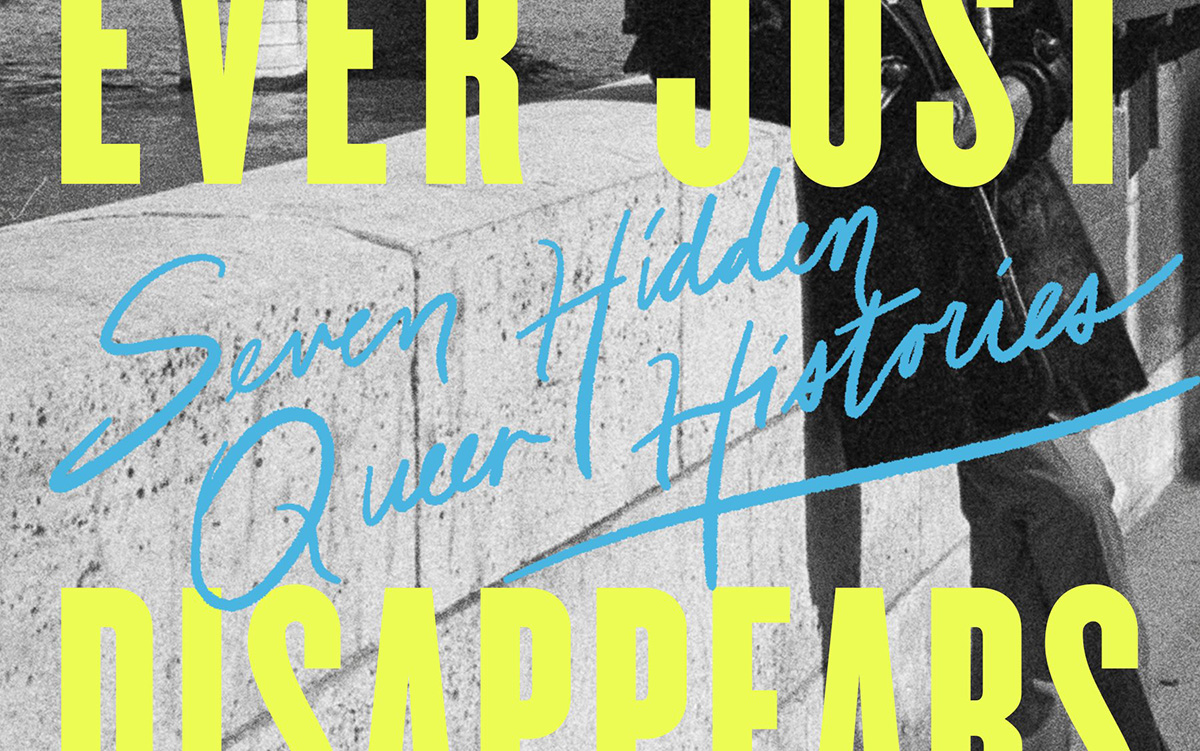

Examining importance of queer places in history of arts and culture

‘Nothing Ever Just Disappears’ shines with grace and lyrical prose

‘Nothing Ever Just Disappears: Seven Hidden Queer Histories’

By Diarmuid Hester

c.2024, Pegasus Books

$29.95/358 pages

Go to your spot.

Where that is comes to mind immediately: a palatial home with soaring windows, or a humble cabin in a glen, a ramshackle treehouse, a window seat, a coffeehouse table, or just a bed with a special blanket. It’s the place where your mind unspools and creativity surges, where you relax, process, and think. It’s the spot where, as in the new book “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” by Diarmuid Hester, you belong.

Clinging “to a spit of land on the south-east coast of England” is Prospect Cottage, where artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman lived until he died of AIDS in 1994. It’s a simple four-room place, but it was important to him. Not long ago, Hester visited Prospect Cottage to “examine the importance of queer places in the history of arts and culture.”

So many “queer spaces” are disappearing. Still, we can talk about those that aren’t.

In his classic book, “Maurice,” writer E.M. Forster imagined the lives of two men who loved one another but could never be together, and their romantic meeting near a second-floor window. The novel, when finished, “proved too radical even for Forster himself.” He didn’t “allow” its publication until after he was dead.

“Patriarchal power,” says Hester, largely controlled who was able to occupy certain spots in London at the turn of the last century. Still, “queer suffragettes” there managed to leave their mark: women like Vera Holme, chauffeur to suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst; writer Virginia Woolf; newspaperwoman Edith Craig, and others who “made enormous contributions to the cause.”

Josephine Baker grew up in poverty, learning to dance to keep warm, but she had Paris, the city that “made her into a star.” Artist and “transgender icon” Claude Cahun loved Jersey, the place where she worked to “show just how much gender is masquerade.” Writer James Baldwin felt most at home in a small town in France. B-filmmaker Jack Smith embraced New York – and vice versa. And on a personal journey, Hester mourns his friend, artist Kevin Killian, who lived and died in his beloved San Francisco.

Juxtaposing place and person, “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” features an interesting way of presenting the idea that both are intertwined deeper than it may seem at first glance. The point is made with grace and lyrical prose, in a storyteller’s manner that offers back story and history as author Diarmuid Hester bemoans the loss of “queer spaces.” This is really a lovely, meaningful book – though readers may argue the points made as they pass through the places included here. Landscapes change with history all the time; don’t modern “queer spaces” count?

That’s a fair question to ask, one that could bring these “hidden” histories full-circle: We often preserve important monuments from history. In memorializing the actions of the queer artists who’ve worked for the future, the places that inspired them are worth enshrining, too.

Reading this book may be the most relaxing, soothing thing you’ll do this month. Try “Nothing Ever Just Disappears” because it really hits the spot.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

-

State Department4 days ago

State Department4 days agoState Department releases annual human rights report

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoCatching up with the asexuals and aromantics of D.C.

-

South America2 days ago

South America2 days agoArgentina government dismisses transgender public sector employees

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoSmithsonian staff concerned about future of LGBTQ programming amid GOP scrutiny